Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. A dog is for life not just for Christmas.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

28th December 2020.

When I first moved to Denmark, the late and great Bengt Saltin told me all about his time spent studying racing Camels in the Middle East. Since that day, my love for comparative physiology blossomed… There are five animals that amaze me: horses, power monsters; cheetahs, speed machines; geese, high-altitude endurance beasts; bears, hibernating muscle-maintaining experts; and dogs, fatigue-resisting marvels. Today, I will “bark lyrical” about our canine friends.

Reading time ~8-mins (1600-words).

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

We all love to watch and admire finely-honed world-class athletes unleashing the beast. Their high VO2max values, high running economies, and high level of fatigue resistance are astounding. Us humans, while we sit on our evolutionary thrones, might think we’re “the dog’s bollocks” when it comes to sporting performance. But, in reality, we suck. Our Earthly brethren out-perform us in many ways. We are lucky they did not evolve complex speech patterns and fire-making skills.

To start to undermine our misplaced self-endowed excellence, let’s get back to those dogs’ bollocks...

We’ve all seen people run with their dogs. I was fortunate to grow up in a household where I did all my long runs with my Dad and our Labrador/Red Setter hybrid, Ben. On our loop through the forests and trails, our four-pawed friend would cover twice our distance in an intermittent sprinting game of “Ooo, a piece of candy… Ooo, a squirrel… Ooo, a deer… Woof”. At the end of the run, my Dad and I would be ruined; Ben would still be chasing cars and harassing anything that moved until he overheated and needed to lie down. Ben was the canine version of Universal Soldier.

A few years ago I was introduced to the world of Canicross by a former coached athlete of mine. Canicross is a speed-fest where humans lash themselves onto their mutts of varying brands and are dragged around the trails at 6-legged speeds. The current 5 km world record surpasses Cheptegai’s 5000m world record!

Canicross sees all breeds of dog unleashing their thing. But, then there is the sled-pulling world of malamutes and huskies.

Malamutes and huskies are related but distinct breeds and are the athletic elite of the mammalian world. The Alaskan Husky seems to be the breed of choice for nurturing a sled-pulling champion. If I am to ever own a dog, it would be one of these “bitches” — they are beautiful. Selectively-bred for endurance and willingness (yes, not all of them want to run), these bad boys are seriously fit.

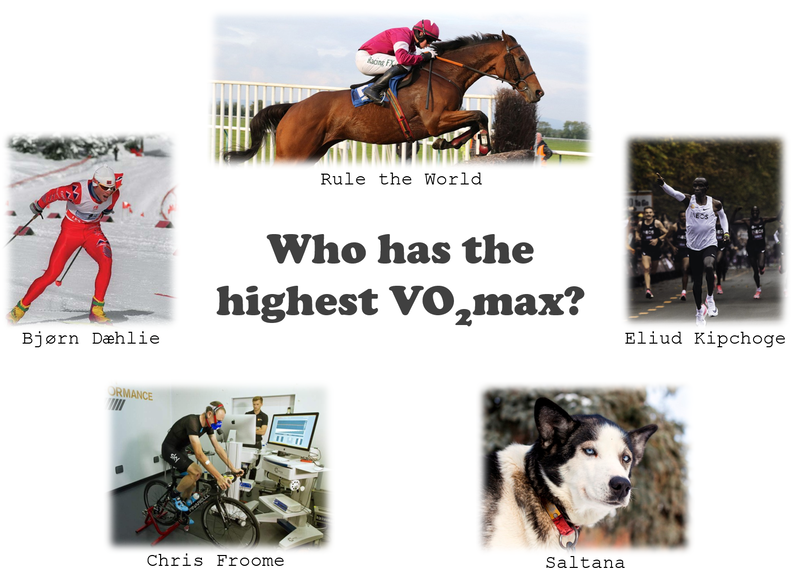

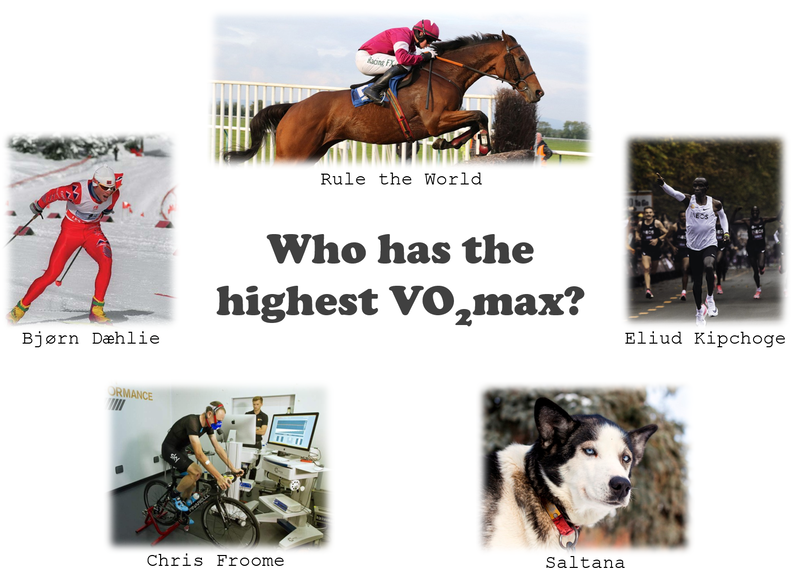

Bjørn Dæhlie, legendary multi world champ and Olympic gold medal-winning cross-country skier;

Bjørn Dæhlie, legendary multi world champ and Olympic gold medal-winning cross-country skier;

Eliud Kipchoge, one of the greatest male endurance runners of all time, world champion from 5000m through to marathon and the first human to run a sub-2-hour marathon;

Eliud Kipchoge, one of the greatest male endurance runners of all time, world champion from 5000m through to marathon and the first human to run a sub-2-hour marathon;

Chris Froome, salbutamol king of the mountains, and multiple Tour de France and Giro D’Italia winning cyclist;

Chris Froome, salbutamol king of the mountains, and multiple Tour de France and Giro D’Italia winning cyclist;

Rule the World, not the Beyoncé song but the thoroughbred racehorse who won the 2016 Grand National; or,

Rule the World, not the Beyoncé song but the thoroughbred racehorse who won the 2016 Grand National; or,

Sultana, the sled-pulling, Iditarod-racing, Alaskan malamute.

Sultana, the sled-pulling, Iditarod-racing, Alaskan malamute.

Seldom do students pick the sled dog.

Sled dogs are epic.

During the Iditarod race in Alaska, a 1600 km (1000 mile) multi-day event, these biological machines can sustain speeds of up to 16 KPH for up to 6- to 8-hours every day... while pulling a sled. (Check out the race here or watch a short clip here.)

Dogs have a superior maximal aerobic capacity and speed.

Dogs have a superior maximal aerobic capacity and speed.

Sled-dogs’ VO2max values have been recorded in excess of 200 ml/kg/min — Eliud Kipchoge’s is somewhere in the region of 70 to 80 — this one of the many reasons sled-dogs can literally run all day, through snow and in icy winds pulling a heavy load. A 2007 study showed that endurance training increased a sled dog’s VO2max by ~10% and their speed at VO2max by 21%! But, more impressive is their pre-training physiology. UNTRAINED dogs had, on average, a VO2max of 180 mL/kg/min and when at VO2max were charging at 6.7 m/s — that’s 2:30 per km, the same pace Cheptegai ran when laying down his 12:35 5000m world record in 2020. Following the 9-week training period, on average, the dogs were galloping at ~8.2 m/s when they reached their VO2max — that’s 2:00 per km, equivalent to a 48-second 400m, a little bit faster than David Rudisha’s 800m 1:40 world record. By the beard of Zeus!

Other studies have delved into Alaskan Husky mitochondria (the muscles’ energy-producing apparatus), showing that they have some of the highest oxygen guzzling capacities ever recorded in mammalian muscle on top of unique mitochondrial adaptations that allow them to maintain a high fraction of their maximal capacity over long distances.

Dogs can synthesise lots of “new” glucose during exercise.

Dogs can synthesise lots of “new” glucose during exercise.

Sled dogs’s ability to “give it large” for up to 8-hours in one push, indicates that they probably have high fat oxidation rates and rely on fat as a fuel to keep propelling their antics. This was indeed the hypothesis of one group who studied the dogs at the Iditarod, but what they found was to the contrary. In 2015, Miller and colleagues showed that while Alaskan Huskies do indeed burn a lot of fat during exercise, participation in the Iditarod increased their rate of carbohydrate oxidation while also increasing their ability to use lactate as a fuel during exercise — similar to what happens in highly-trained humans. But they also found that to allow such high rates of “carb burning” during exercise, these dogs had a remarkable adaptation that allowed them to maintain normal blood glucose — their liver took up large amounts of glycerol from the blood to produce new glucose (gluconeogenesis) — unlike us humans, who have a relatively miniscule capacity for gluconeogenesis and maintaining blood glucose during prolonged, high-intensity work.

So, sled dogs can give it large for hours by burning large amounts of glucose to produce energy in their muscles, while maintaining blood glucose using circulating fat breakdown products. Accordingly, training causes metabolic adaptations that improve sled dogs’ muscles’ use of carbohydrates as a fuel, allowing maximal glucose oxidation rates to be achieved. This means that when sled-dogs give it large moving at high speed for up to 8-hours in one push, they are also sustaining a very high fraction of their maximal aerobic capacity — much like the best human endurance athletes.

Dogs rapidly re-synthesise muscle glycogen after exercise even without eating carbohydrate.

Dogs rapidly re-synthesise muscle glycogen after exercise even without eating carbohydrate.

Just like us humans, dogs need to replenish their muscle glycogen after hard long efforts and providing carbohydrates in their food helps them do so. While post-exercise carb ingestion expectedly increases muscle glycogen resynthesis to rapidly-restore pre-exercise glycogen levels, it is remarkable that sled dogs can resynthesise nearly 40% of their muscle glycogen during the 24-hour period after exercise when receiving nothing but water — humans cannot do this. Even when gunning it for up to 160 km per day for several consecutive days, Alaskan Husky sled dogs have an incredible ability to maintain muscle glycogen — it is very challenging for humans to maintain muscle glycogen during multi-day ultra-distance events; dogs, on the other hand, no sweat!

Dogs eat a lot of calories — a high-fat diet that contains a lot of carbs.

Dogs eat a lot of calories — a high-fat diet that contains a lot of carbs.

Sled dogs typically consume a high-fat diet — about 50% of calories from fat — with about 30% coming from protein and less than 20% of calories coming from carbohydrates. So, it is easy to assume that dogs are low-carb or “keto”. Alas, they are not. Daily energy intake of an exercising sled dog is estimated to be in the range of 4000 to 11,000 kcals per day! On average, during an endurance race, they take on ~8000 kcals/day, which means that, with ~20% of energy coming from carbohydrate, they eat about 400 grams of carbs per day. In a 25 kg dog, this is about 16 grams per kilo body mass — for us humans to maintain a high carbohydrate availability during a period of highly intense training, it is recommended to eat 10 to 12 grams per kilo per day.

The high fat content in a sled dog’s diet helps them maintain high muscle triglyceride levels while also helping them spare glycogen during intense exercise — the same thing happens in fat-munching humans except that we lose our high-end speed. But, unlike humans, switching a sled dog to a high carb diet doesn’t influence their muscle glycogen levels. Again, dogs have a remarkable capacity to resynthesis glycogen even with low carbohydrate intake! Woof.

Dogs adapt rapidly to exercise.

Dogs adapt rapidly to exercise.

A cool study that followed 48 Alaskan sled-dogs running 140 km for 4 consecutive days, found that muscle glycogen and muscle triglycerides were depleted during each run but by the 4th day, muscle glycogen use during exercise was close to zero — humans do not adapt like this!

Sled dogs also need a high daily protein intake to support the needs of muscle protein synthesis for repair, growth, and adaptations — just like humans. However, muscle protein synthesis rates are much higher in sled dogs than in humans and the rate of mitochondrial protein turnover is super high in Alaskan Huskies. This allows them to rapidly adapt to environmental extremes and large training (or racing) stimuli. But this greater turnover of muscle protein means that sled dogs’ need for daily protein intake is also higher than in humans. This is supported by their high meat (protein) intake — around 30% of daily calories — which, when racing with a daily intake of around 8000 kcals, is equivalent to around 600 grams of protein each day, or about 24 grams per kilo body weight in a 25 kg sled dog. Compare this to us humans, in whom a daily protein intake of 1.2 to 2 grams/kg per day is sufficient to support muscle protein synthesis and other bodily protein needs — a far-lower relative protein intake to support a far-lower protein turnover rate, when compared to a highly-active sled dog.

So, dogs truly are fatigue-resisting marvels — you will never outperform your dog! Sled dogs in particular have superior physiology, enhanced adaptations to exercise, and clever mechanisms for preventing hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose) during prolonged high-intensity exercise.

The next time your “Santa’s Little Helper'' chews up one of your running shoes, she is probably giving you a clue… take her out for a daily spin.

Your dog is for life not just for Christmas!

Have a good one folks!

To start to undermine our misplaced self-endowed excellence, let’s get back to those dogs’ bollocks...

We’ve all seen people run with their dogs. I was fortunate to grow up in a household where I did all my long runs with my Dad and our Labrador/Red Setter hybrid, Ben. On our loop through the forests and trails, our four-pawed friend would cover twice our distance in an intermittent sprinting game of “Ooo, a piece of candy… Ooo, a squirrel… Ooo, a deer… Woof”. At the end of the run, my Dad and I would be ruined; Ben would still be chasing cars and harassing anything that moved until he overheated and needed to lie down. Ben was the canine version of Universal Soldier.

A few years ago I was introduced to the world of Canicross by a former coached athlete of mine. Canicross is a speed-fest where humans lash themselves onto their mutts of varying brands and are dragged around the trails at 6-legged speeds. The current 5 km world record surpasses Cheptegai’s 5000m world record!

Canicross sees all breeds of dog unleashing their thing. But, then there is the sled-pulling world of malamutes and huskies.

Malamutes and huskies are related but distinct breeds and are the athletic elite of the mammalian world. The Alaskan Husky seems to be the breed of choice for nurturing a sled-pulling champion. If I am to ever own a dog, it would be one of these “bitches” — they are beautiful. Selectively-bred for endurance and willingness (yes, not all of them want to run), these bad boys are seriously fit.

×

![]()

I always love teaching medical students and exercise science undergrads about the comparative physiology of work capacity. In doing so, I usually start by giving them the opportunity to select between fine specimens to answer the question, “Who has the highest relative VO2max?”...

×

![]()

The consensus answer is always wrong — some choose the horse but the vast majority of students choose the cross-country skier.

Seldom do students pick the sled dog.

Sled dogs are epic.

Comparative Physiology — Dogs go “Woof”!

Sled dogs have been essential for human survival in polar regions for many moons; used by native Eskimo and polar explorers. Sled dogs are also used for recreation and racing. In the 1950s, physiological data began to emerge... 70-years on, we have true appreciation and understanding of their phenomenal capacity for work output.During the Iditarod race in Alaska, a 1600 km (1000 mile) multi-day event, these biological machines can sustain speeds of up to 16 KPH for up to 6- to 8-hours every day... while pulling a sled. (Check out the race here or watch a short clip here.)

Sled-dogs’ VO2max values have been recorded in excess of 200 ml/kg/min — Eliud Kipchoge’s is somewhere in the region of 70 to 80 — this one of the many reasons sled-dogs can literally run all day, through snow and in icy winds pulling a heavy load. A 2007 study showed that endurance training increased a sled dog’s VO2max by ~10% and their speed at VO2max by 21%! But, more impressive is their pre-training physiology. UNTRAINED dogs had, on average, a VO2max of 180 mL/kg/min and when at VO2max were charging at 6.7 m/s — that’s 2:30 per km, the same pace Cheptegai ran when laying down his 12:35 5000m world record in 2020. Following the 9-week training period, on average, the dogs were galloping at ~8.2 m/s when they reached their VO2max — that’s 2:00 per km, equivalent to a 48-second 400m, a little bit faster than David Rudisha’s 800m 1:40 world record. By the beard of Zeus!

Other studies have delved into Alaskan Husky mitochondria (the muscles’ energy-producing apparatus), showing that they have some of the highest oxygen guzzling capacities ever recorded in mammalian muscle on top of unique mitochondrial adaptations that allow them to maintain a high fraction of their maximal capacity over long distances.

Sled dogs’s ability to “give it large” for up to 8-hours in one push, indicates that they probably have high fat oxidation rates and rely on fat as a fuel to keep propelling their antics. This was indeed the hypothesis of one group who studied the dogs at the Iditarod, but what they found was to the contrary. In 2015, Miller and colleagues showed that while Alaskan Huskies do indeed burn a lot of fat during exercise, participation in the Iditarod increased their rate of carbohydrate oxidation while also increasing their ability to use lactate as a fuel during exercise — similar to what happens in highly-trained humans. But they also found that to allow such high rates of “carb burning” during exercise, these dogs had a remarkable adaptation that allowed them to maintain normal blood glucose — their liver took up large amounts of glycerol from the blood to produce new glucose (gluconeogenesis) — unlike us humans, who have a relatively miniscule capacity for gluconeogenesis and maintaining blood glucose during prolonged, high-intensity work.

So, sled dogs can give it large for hours by burning large amounts of glucose to produce energy in their muscles, while maintaining blood glucose using circulating fat breakdown products. Accordingly, training causes metabolic adaptations that improve sled dogs’ muscles’ use of carbohydrates as a fuel, allowing maximal glucose oxidation rates to be achieved. This means that when sled-dogs give it large moving at high speed for up to 8-hours in one push, they are also sustaining a very high fraction of their maximal aerobic capacity — much like the best human endurance athletes.

Just like us humans, dogs need to replenish their muscle glycogen after hard long efforts and providing carbohydrates in their food helps them do so. While post-exercise carb ingestion expectedly increases muscle glycogen resynthesis to rapidly-restore pre-exercise glycogen levels, it is remarkable that sled dogs can resynthesise nearly 40% of their muscle glycogen during the 24-hour period after exercise when receiving nothing but water — humans cannot do this. Even when gunning it for up to 160 km per day for several consecutive days, Alaskan Husky sled dogs have an incredible ability to maintain muscle glycogen — it is very challenging for humans to maintain muscle glycogen during multi-day ultra-distance events; dogs, on the other hand, no sweat!

Sled dogs typically consume a high-fat diet — about 50% of calories from fat — with about 30% coming from protein and less than 20% of calories coming from carbohydrates. So, it is easy to assume that dogs are low-carb or “keto”. Alas, they are not. Daily energy intake of an exercising sled dog is estimated to be in the range of 4000 to 11,000 kcals per day! On average, during an endurance race, they take on ~8000 kcals/day, which means that, with ~20% of energy coming from carbohydrate, they eat about 400 grams of carbs per day. In a 25 kg dog, this is about 16 grams per kilo body mass — for us humans to maintain a high carbohydrate availability during a period of highly intense training, it is recommended to eat 10 to 12 grams per kilo per day.

The high fat content in a sled dog’s diet helps them maintain high muscle triglyceride levels while also helping them spare glycogen during intense exercise — the same thing happens in fat-munching humans except that we lose our high-end speed. But, unlike humans, switching a sled dog to a high carb diet doesn’t influence their muscle glycogen levels. Again, dogs have a remarkable capacity to resynthesis glycogen even with low carbohydrate intake! Woof.

A cool study that followed 48 Alaskan sled-dogs running 140 km for 4 consecutive days, found that muscle glycogen and muscle triglycerides were depleted during each run but by the 4th day, muscle glycogen use during exercise was close to zero — humans do not adapt like this!

Sled dogs also need a high daily protein intake to support the needs of muscle protein synthesis for repair, growth, and adaptations — just like humans. However, muscle protein synthesis rates are much higher in sled dogs than in humans and the rate of mitochondrial protein turnover is super high in Alaskan Huskies. This allows them to rapidly adapt to environmental extremes and large training (or racing) stimuli. But this greater turnover of muscle protein means that sled dogs’ need for daily protein intake is also higher than in humans. This is supported by their high meat (protein) intake — around 30% of daily calories — which, when racing with a daily intake of around 8000 kcals, is equivalent to around 600 grams of protein each day, or about 24 grams per kilo body weight in a 25 kg sled dog. Compare this to us humans, in whom a daily protein intake of 1.2 to 2 grams/kg per day is sufficient to support muscle protein synthesis and other bodily protein needs — a far-lower relative protein intake to support a far-lower protein turnover rate, when compared to a highly-active sled dog.

The next time your “Santa’s Little Helper'' chews up one of your running shoes, she is probably giving you a clue… take her out for a daily spin.

Your dog is for life not just for Christmas!

Have a good one folks!

×

![]()

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.