The Sports Supplements Tool from Thomas Solomon PhD.

Which sports supplements work for runners and endurance athletes?

Last updated on: 15th July 2024.

Next update coming: July 2025.

Next update coming: July 2025.

Optimal performance is achieved with a well-planned and monitored training load combined with good nutrition, sleep, and rest. Lots of athletes also choose to use supplements. However, sports supplements are a big and confusing business — you can easily get lost and waste a lot of time and money. This free tool is an up-to-date summary of all known scientific evidence determining the effect of sports supplements on exercise performance. It can be used in combination with my Recovery Magic Tool. I’ve designed these resources for scientists, practitioners, coaches, and athletes to help inform their decisions. I aim to keep them up-to-date as new evidence emerges.

Is this your first time using this tool?  I strongly recommend reading the intro section below (500 words; 3 min read) because it contains important information about how you can learn to make informed decisions about choosing supplements. However, if you’ve already read the intro below, click the arrow to jump down to the tool.

I strongly recommend reading the intro section below (500 words; 3 min read) because it contains important information about how you can learn to make informed decisions about choosing supplements. However, if you’ve already read the intro below, click the arrow to jump down to the tool.

To quote Louise Burke and John Hawley, “Modern sports nutrition offers a feast of opportunities to assist elite athletes to train hard, optimize adaptation, stay healthy and injury free, achieve their desired physique, and fight against fatigue factors that limit success.”. But, when I think about sports supplements, Ron Maughan’s poetry always rolls through my mind: “If it works, it’s probably banned… If it’s not banned, then it probably doesn’t work… There may be some exceptions.”

Functional claims about a specific product are usually made in line with a specific functional dose of the active ingredient. If a product doesn’t contain a sufficient dose then it definitely won’t have the intended effect. Since the FDA/FSA do not systematically monitor supplements, you will often read “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”. So, you need confidence in knowing exactly what’s in the bottle of pills or potion you are taking. And, as an athlete, quality control is essential! Without it, you may harm your health or take a contaminated product. And this is where things start to fall apart… Several reports have found major discrepancies between claimed contents and actual content (e.g. ephedra and CBD supplements), while even some controlled drugs, like the steroid hormone dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), have slipped through the net and been sold as dietary supplements. Plus, a 2022 systematic review found that 28% (or 875 out of 3132) supplements contained undeclared substances (including stimulants and anabolic steroids) that would trigger a positive doping test. This is worrying because, according to the NURMI study, ~50% of runners use supplements and a 2007 IAAF/World Athletics report found that ~85% of elite track and field athletes used dietary and/or sports supplements. The supplement business is booming!

“It definitely works!”

I've lost count of how many times I’ve heard social media influencers spew the “I've used this and it was awesome” narrative. Regrettably, such phrases are also spouted from the mouths of “reputable” athletes, coaches, and other practitioners including scientists, nutritionists, psychologists, physiologists, and medical doctors on podcast, radio, and TV interviews when talking about a new pill, potion, or device. Frustratingly, these folks rarely say what “it” works for, what “it” is being compared to, or whether using “it” made them objectively faster, stronger, or healthier. When you see such narratives, think to yourself:

“It definitely works!”

I've lost count of how many times I’ve heard social media influencers spew the “I've used this and it was awesome” narrative. Regrettably, such phrases are also spouted from the mouths of “reputable” athletes, coaches, and other practitioners including scientists, nutritionists, psychologists, physiologists, and medical doctors on podcast, radio, and TV interviews when talking about a new pill, potion, or device. Frustratingly, these folks rarely say what “it” works for, what “it” is being compared to, or whether using “it” made them objectively faster, stronger, or healthier. When you see such narratives, think to yourself:

Were appropriate baseline measurements made?

Were appropriate baseline measurements made?

What were the baseline measurements?

What were the baseline measurements?

When were the baseline measurements followed up?

When were the baseline measurements followed up?

Did the baseline measurements actually change after the intervention period?

Did the baseline measurements actually change after the intervention period?

Did the person make any other lifestyle changes during the intervention period?

Did the person make any other lifestyle changes during the intervention period?

Is the person being paid or sponsored to promote the product? And, so on…

Is the person being paid or sponsored to promote the product? And, so on…

To bring clarity where there is obscurity and help you understand whether “it” might actually improve performance and/or recovery, I’ve dug into all known scientific evidence on this topic and created a free resource to help inform your decisions.

High-quality robust evidence comes from studies with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. But, “cherry-picking” a study to confirm a bias is not a valid pursuit for informing practice. A systematic review examines all the “cherries” in a standardised way and, when the studies included in a systematic review are of high enough quality, a meta-analysis of all the available data can be completed. This produces an overall effect size along with a 95% confidence interval (the range of values the real effect size is likely to be found if the intervention is repeated) and a heterogeneity score (how variable the effect is). In simple words, a meta-analysis analyses all the “cherries” simultaneously to produce a useable effect size based on all available scientific evidence, enabling good decisions to be made. So, when I say that “I’ve dug into all known scientific evidence”, I mean that I’ve read all known systematic reviews and meta-analyses and summarised the evidence in this free resource: the Sports Supplements Tool.

But, before making any decisions, always conduct a cost-benefit analysis, where “cost” includes a combination of financial costs, time costs, moral costs, risk of contamination, potential performance impairment, and harm to health. For example:

If there is no benefit, there is no point in using the supplement.

If there is no benefit, there is no point in using the supplement.

If there is a benefit and no (or little) cost, use the supplement; you’d be foolish not to.

If there is a benefit and no (or little) cost, use the supplement; you’d be foolish not to.

If the cost outweighs the benefit, do not proceed.

If the cost outweighs the benefit, do not proceed.

When making this kind of cost-benefit analysis, always remember that:

Taking a supplement does not “make” an athlete.

Taking a supplement does not “make” an athlete.

A supplement does not replace training.

A supplement does not replace training.

A dietary supplement does not replace food.

A dietary supplement does not replace food.

There is no such thing as “exercise in a pill”.

There is no such thing as “exercise in a pill”.

It is also important to know that if you use supplements of any kind and/or prescription or over-the-counter drugs, you are also putting yourself at an increased risk of a positive test because they can contain prohibited substances. Minimise this risk by taking the following steps:

Educate yourself by completing European Athletics’ I Run Clean certification.

Educate yourself by completing European Athletics’ I Run Clean certification.

Familiarise yourself with the rules of your sport and with WADA’s prohibited list, which is updated every January.

Familiarise yourself with the rules of your sport and with WADA’s prohibited list, which is updated every January.

If you are using ANY sports (or dietary) supplement, ensure it has been independently tested for prohibited substances by Informed Sport (or similar) → If in doubt, spit it out!

If you are using ANY sports (or dietary) supplement, ensure it has been independently tested for prohibited substances by Informed Sport (or similar) → If in doubt, spit it out!

If you are using ANY over-the-counter or prescribed drugs, ALWAYS know what you are taking and get in the habit of cross-checking the Global DRO to help determine whether you need a TUE (therapeutic use exemption).

If you are using ANY over-the-counter or prescribed drugs, ALWAYS know what you are taking and get in the habit of cross-checking the Global DRO to help determine whether you need a TUE (therapeutic use exemption).

And, always remember that:

You are the only person responsible for what goes into your body.

You are the only person responsible for what goes into your body.

Ignorance is not an excuse.

Ignorance is not an excuse.

Stay educated. Be informed. Encourage others to do the same.

Stay educated. Be informed. Encourage others to do the same.

OK… You’re now ready for some science.

Functional claims about a specific product are usually made in line with a specific functional dose of the active ingredient. If a product doesn’t contain a sufficient dose then it definitely won’t have the intended effect. Since the FDA/FSA do not systematically monitor supplements, you will often read “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”. So, you need confidence in knowing exactly what’s in the bottle of pills or potion you are taking. And, as an athlete, quality control is essential! Without it, you may harm your health or take a contaminated product. And this is where things start to fall apart… Several reports have found major discrepancies between claimed contents and actual content (e.g. ephedra and CBD supplements), while even some controlled drugs, like the steroid hormone dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), have slipped through the net and been sold as dietary supplements. Plus, a 2022 systematic review found that 28% (or 875 out of 3132) supplements contained undeclared substances (including stimulants and anabolic steroids) that would trigger a positive doping test. This is worrying because, according to the NURMI study, ~50% of runners use supplements and a 2007 IAAF/World Athletics report found that ~85% of elite track and field athletes used dietary and/or sports supplements. The supplement business is booming!

To bring clarity where there is obscurity and help you understand whether “it” might actually improve performance and/or recovery, I’ve dug into all known scientific evidence on this topic and created a free resource to help inform your decisions.

High-quality robust evidence comes from studies with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. But, “cherry-picking” a study to confirm a bias is not a valid pursuit for informing practice. A systematic review examines all the “cherries” in a standardised way and, when the studies included in a systematic review are of high enough quality, a meta-analysis of all the available data can be completed. This produces an overall effect size along with a 95% confidence interval (the range of values the real effect size is likely to be found if the intervention is repeated) and a heterogeneity score (how variable the effect is). In simple words, a meta-analysis analyses all the “cherries” simultaneously to produce a useable effect size based on all available scientific evidence, enabling good decisions to be made. So, when I say that “I’ve dug into all known scientific evidence”, I mean that I’ve read all known systematic reviews and meta-analyses and summarised the evidence in this free resource: the Sports Supplements Tool.

But, before making any decisions, always conduct a cost-benefit analysis, where “cost” includes a combination of financial costs, time costs, moral costs, risk of contamination, potential performance impairment, and harm to health. For example:

When making this kind of cost-benefit analysis, always remember that:

It is also important to know that if you use supplements of any kind and/or prescription or over-the-counter drugs, you are also putting yourself at an increased risk of a positive test because they can contain prohibited substances. Minimise this risk by taking the following steps:

And, always remember that:

OK… You’re now ready for some science.

Caffeine, aka 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine, is a psychoactive drug that acts as a stimulant. While caffeine plays a role in calcium transport in muscle cells, it primarily affects your central nervous system by preventing adenosine binding to its receptors. This essentially blocks the “motivation-dampening” effects of adenosine, allowing “motivating” neurotransmitters like dopamine to continue to be released.

But caffeine has side effects, which can include a speedy heart rate (tachycardia), heart palpitations, headache, insomnia, peeing more, nervousness, gastrointestinal problems, and so on. If you develop any such symptoms as a consequence of caffeine intake before, during, or after races, you’re probably using too much. These side effects combined with frequent media stories about the risks of caffeine-containing high-sugar energy drinks, beg the important question: cIs caffeine dangerous?

A 2017 systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine concluded that “Consumption of up to 400 mg caffeine/day in healthy adults is not associated with overt, adverse cardiovascular effects, behavioral effects, reproductive and developmental effects, acute effects, or bone status. Evidence also supports consumption of up to 300 mg caffeine/day in healthy pregnant women as an intake that is generally not associated with adverse reproductive and developmental effects.”.

A 2017 umbrella review of meta-analyses concluded that “Coffee consumption seems generally safe within usual levels of intake”, and a 2022 systematic review of the side effects of caffeine supplementation in sport concluded that “Athletes using caffeine supplementation to enhance performance should be aware of both benefits and risks associated with the use of this substance in the sports context.” and that “From a practical perspective, supplementation with ~3.0 mg/kg of caffeine may be the dose of choice to combine the ergogenic benefits of caffeine with a low prevalence of side effects.”

Furthermore, a randomised controlled crossover trial published in 2023 in the New England Journal of Medicine, which included continuous ECG measurements for 2 weeks, found that drinking more caffeinated coffee than usual might increase the number of premature ventricular contractions but does not increase the number of unusual heart rhythms (atrial arrhythmias) in healthy adults.

So, caffeine is generally safe for most people if used within the recommended amounts.

Therefore, it is no surprise that a lot of people use caffeine as a way to start (and continue) their day. Bonjour, coffee. By extension, since endurance athletes are also people, we can assume that many athletes also indulge in a daily caffeine fix. But, we can be more objective and examine epidemiology. A survey of 24,808 adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that ~89% of US adults consume caffeine daily. Meanwhile, a 2022 survey of 254 endurance athletes found that 85% of athletes reported daily caffeine consumption (in beverages), 41% reported multiple daily caffeine intake, but only 24% reported purposefully using caffeine supplements prior to or during sessions and races. So…

Does caffeine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Does caffeine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

To conclude…

This tool is free. Please help keep it alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. Want free info like this in your inbox? Sign up here:

Full list of systematic reviews examining caffeine for performance.

Here is the list of systematic reviews I have summarised above.

Effect of Acute Caffeine Intake on Fat Oxidation Rate during Fed-State Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fernández-Sánchez J, Trujillo-Colmena D, Rodríguez-Castaño A, Lavín-Pérez AM, Del Coso J, Casado A, Collado-Mateo D. Nutrients (2024)

Effect of Acute Caffeine Intake on Fat Oxidation Rate during Fed-State Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fernández-Sánchez J, Trujillo-Colmena D, Rodríguez-Castaño A, Lavín-Pérez AM, Del Coso J, Casado A, Collado-Mateo D. Nutrients (2024)

Effects of Acute Ingestion of Caffeine Capsules on Muscle Strength and Muscle Endurance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Wu W, Chen Z, Zhou H, Wang L, Li X, Lv Y, Sun T, Yu L. Nutrients (2024)

Effects of Acute Ingestion of Caffeine Capsules on Muscle Strength and Muscle Endurance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Wu W, Chen Z, Zhou H, Wang L, Li X, Lv Y, Sun T, Yu L. Nutrients (2024)

Caffeine, CYP1A2 Genotype and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Barreto, Gabriel; Esteves, Gabriel P; Marticorena, Felipe; Oliveira, Tamires N; Grgic, Jozo; Saunders, Bryan. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2023)

Caffeine, CYP1A2 Genotype and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Barreto, Gabriel; Esteves, Gabriel P; Marticorena, Felipe; Oliveira, Tamires N; Grgic, Jozo; Saunders, Bryan. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2023)

The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Carissa Gardiner, Jonathon Weakley, Louise M. Burke, Gregory D. Roach, Charli Sargent, Nirav Maniar, Andrew Townshend, Shona L. Halson. Sleep Med Rev (2023)

The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Carissa Gardiner, Jonathon Weakley, Louise M. Burke, Gregory D. Roach, Charli Sargent, Nirav Maniar, Andrew Townshend, Shona L. Halson. Sleep Med Rev (2023)

International society of sports nutrition position stand: coffee and sports performance. Lowery et al. (2023) J Int Soc Sports Nutr

International society of sports nutrition position stand: coffee and sports performance. Lowery et al. (2023) J Int Soc Sports Nutr

Effects of Caffeine Intake on Endurance Running Performance and Time to Exhaustion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ziyu Wang, Bopeng Qiu, Jie Gao, Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2022)

Effects of Caffeine Intake on Endurance Running Performance and Time to Exhaustion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ziyu Wang, Bopeng Qiu, Jie Gao, Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2022)

Acute Effects of Caffeine on Overall Performance in Basketball Players-A Systematic Review. Anja Lazić, Miodrag Kocić, Nebojša Trajković, Cristian Popa, Leonardo Alexandre Peyré-Tartaruga, Johnny Padulo. Nutrients (2022)

Acute Effects of Caffeine on Overall Performance in Basketball Players-A Systematic Review. Anja Lazić, Miodrag Kocić, Nebojša Trajković, Cristian Popa, Leonardo Alexandre Peyré-Tartaruga, Johnny Padulo. Nutrients (2022)

Effect of Pre-Exercise Caffeine Intake on Endurance Performance and Core Temperature Regulation During Exercise in the Heat: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Catherine Naulleau, David Jeker, Timothée Pancrate, Pascale Claveau, Thomas A Deshayes, Louise M Burke, Eric D B Goulet. Sports Med (2022)

Effect of Pre-Exercise Caffeine Intake on Endurance Performance and Core Temperature Regulation During Exercise in the Heat: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Catherine Naulleau, David Jeker, Timothée Pancrate, Pascale Claveau, Thomas A Deshayes, Louise M Burke, Eric D B Goulet. Sports Med (2022)

Exploring the minimum ergogenic dose of caffeine on resistance exercise performance: A meta-analytic approach. Jozo Grgic. Nutr (2022)

Exploring the minimum ergogenic dose of caffeine on resistance exercise performance: A meta-analytic approach. Jozo Grgic. Nutr (2022)

Risk or benefit? Side effects of caffeine supplementation in sport: a systematic review. Jefferson Gomes de Souza, Juan Del Coso, Fabiano de Souza Fonseca, Bruno Victor Corrêa Silva, Diego Brito de Souza, Rodrigo Luiz da Silva Gianoni, Aleksandra Filip-Stachnik, Julio Cerca Serrão, João Gustavo Claudino. Eur J Nutr (2022)

Risk or benefit? Side effects of caffeine supplementation in sport: a systematic review. Jefferson Gomes de Souza, Juan Del Coso, Fabiano de Souza Fonseca, Bruno Victor Corrêa Silva, Diego Brito de Souza, Rodrigo Luiz da Silva Gianoni, Aleksandra Filip-Stachnik, Julio Cerca Serrão, João Gustavo Claudino. Eur J Nutr (2022)

Effects of acute caffeine intake on combat sports performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Javier Diaz-Lara, Jozo Grgic, Daniele Detanico, Javier Botella, Sergio L Jiménez, Juan Del Coso. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Effects of acute caffeine intake on combat sports performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Javier Diaz-Lara, Jozo Grgic, Daniele Detanico, Javier Botella, Sergio L Jiménez, Juan Del Coso. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Effects of caffeine on rate of force development: A meta-analysis. Jozo Grgic, Pavle Mikulic. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2022)

Effects of caffeine on rate of force development: A meta-analysis. Jozo Grgic, Pavle Mikulic. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2022)

Supplementation and Performance for Wheelchair Athletes: A Systematic Review. Andreia Bauermann, Karina S G de Sá, Zilda A Santos, Anselmo A Costa E Silva. Adapt Phys Activ Q (2022)

Supplementation and Performance for Wheelchair Athletes: A Systematic Review. Andreia Bauermann, Karina S G de Sá, Zilda A Santos, Anselmo A Costa E Silva. Adapt Phys Activ Q (2022)

Acute caffeine supplementation and live match-play performance in team-sports: A systematic review (2000-2021). Adriano Arguedas-Soley, Isobel Townsend, Aaron Hengist, James Betts. J Sports Sci (2022)

Acute caffeine supplementation and live match-play performance in team-sports: A systematic review (2000-2021). Adriano Arguedas-Soley, Isobel Townsend, Aaron Hengist, James Betts. J Sports Sci (2022)

Interaction Between Caffeine and Creatine When Used as Concurrent Ergogenic Supplements: A Systematic Review. Sara Elosegui, Jaime López-Seoane, María Martínez-Ferrán, Helios Pareja-Galeano. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Interaction Between Caffeine and Creatine When Used as Concurrent Ergogenic Supplements: A Systematic Review. Sara Elosegui, Jaime López-Seoane, María Martínez-Ferrán, Helios Pareja-Galeano. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Synergy of carbohydrate and caffeine ingestion on physical performance and metabolic responses to exercise: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Jaime López-Seoane, Marta Buitrago-Morales, Sergio L Jiménez, Juan Del Coso, Helios Pareja-Galeano. . Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Synergy of carbohydrate and caffeine ingestion on physical performance and metabolic responses to exercise: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Jaime López-Seoane, Marta Buitrago-Morales, Sergio L Jiménez, Juan Del Coso, Helios Pareja-Galeano. . Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Does Caffeine Increase Fat Metabolism? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Scott A. Conger, Lara M. Tuthill, Mindy L. Millard-Stafford. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Does Caffeine Increase Fat Metabolism? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Scott A. Conger, Lara M. Tuthill, Mindy L. Millard-Stafford. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Effects of Caffeine Intake on Endurance Running Performance and Time to Exhaustion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ziyu Wang, Bopeng Qiu, Jie Gao, and Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2022)

Effects of Caffeine Intake on Endurance Running Performance and Time to Exhaustion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ziyu Wang, Bopeng Qiu, Jie Gao, and Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2022)

Acute Effects of Caffeine Supplementation on Physical Performance, Physiological Responses, Perceived Exertion, and Technical-Tactical Skills in Combat Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Slaheddine Delleli, Ibrahim Ouergui, Hamdi Messaoudi, Khaled Trabelsi, Achraf Ammar, Jordan M. Glenn and Hamdi Chtourou. Nutrients (2022)

Acute Effects of Caffeine Supplementation on Physical Performance, Physiological Responses, Perceived Exertion, and Technical-Tactical Skills in Combat Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Slaheddine Delleli, Ibrahim Ouergui, Hamdi Messaoudi, Khaled Trabelsi, Achraf Ammar, Jordan M. Glenn and Hamdi Chtourou. Nutrients (2022)

Effects of caffeine ingestion on cardiopulmonary responses during a maximal graded exercise test: a systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Alisson Henrique Marinho, João Paulo Lopes-Silva, Gislaine Cristina-Souza, Filipe Antônio de Barros Sousa, Thays Ataide-Silva, Adriano Eduardo Lima-Silva, Gustavo Gomes de Araujo, Marcos David Silva-Cavalcante. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Effects of caffeine ingestion on cardiopulmonary responses during a maximal graded exercise test: a systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Alisson Henrique Marinho, João Paulo Lopes-Silva, Gislaine Cristina-Souza, Filipe Antônio de Barros Sousa, Thays Ataide-Silva, Adriano Eduardo Lima-Silva, Gustavo Gomes de Araujo, Marcos David Silva-Cavalcante. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2022)

Effects of caffeine chewing gum supplementation on exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. G Barreto, L M R Loureiro, C E G Reis, B Saunders. Eur J Sport Sci (2022)

Effects of caffeine chewing gum supplementation on exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. G Barreto, L M R Loureiro, C E G Reis, B Saunders. Eur J Sport Sci (2022)

Can I Have My Coffee and Drink It? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Determine Whether Habitual Caffeine Consumption Affects the Ergogenic Effect of Caffeine. Arthur Carvalho, Felipe Miguel Marticorena, Beatriz Helena Grecco, Gabriel Barreto, Bryan Saunders. Sports Med (2022)

Can I Have My Coffee and Drink It? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis to Determine Whether Habitual Caffeine Consumption Affects the Ergogenic Effect of Caffeine. Arthur Carvalho, Felipe Miguel Marticorena, Beatriz Helena Grecco, Gabriel Barreto, Bryan Saunders. Sports Med (2022)

Effects of caffeine on isometric handgrip strength: A meta-analysis. Jozo Grgic. Clin Nutr ESPEN (2022)

Effects of caffeine on isometric handgrip strength: A meta-analysis. Jozo Grgic. Clin Nutr ESPEN (2022)

International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. Nanci S Guest, Trisha A VanDusseldorp, Michael T Nelson Jozo Grgic, Brad J Schoenfeld, Nathaniel D M Jenkins, Shawn M Arent, Jose Antonio, Jeffrey R Stout, Eric T Trexler, Abbie E Smith-Ryan, Erica R Goldstein, Douglas S Kalman, Bill I Campbell. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. Nanci S Guest, Trisha A VanDusseldorp, Michael T Nelson Jozo Grgic, Brad J Schoenfeld, Nathaniel D M Jenkins, Shawn M Arent, Jose Antonio, Jeffrey R Stout, Eric T Trexler, Abbie E Smith-Ryan, Erica R Goldstein, Douglas S Kalman, Bill I Campbell. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

Ergogenic Effects of Acute Caffeine Intake on Muscular Endurance and Muscular Strength in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Jozo Grgic, Juan Del Coso. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021)

Ergogenic Effects of Acute Caffeine Intake on Muscular Endurance and Muscular Strength in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Jozo Grgic, Juan Del Coso. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021)

Does Acute Caffeine Supplementation Improve Physical Performance in Female Team-Sport Athletes? Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alejandro Gomez-Bruton, Jorge Marin-Puyalto, Borja Muñiz-Pardos, Angel Matute-Llorente, Juan Del Coso, Alba Gomez-Cabello, German Vicente-Rodriguez, Jose A Casajus, Gabriel Lozano-Berges. Nutrients (2021)

Does Acute Caffeine Supplementation Improve Physical Performance in Female Team-Sport Athletes? Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alejandro Gomez-Bruton, Jorge Marin-Puyalto, Borja Muñiz-Pardos, Angel Matute-Llorente, Juan Del Coso, Alba Gomez-Cabello, German Vicente-Rodriguez, Jose A Casajus, Gabriel Lozano-Berges. Nutrients (2021)

Does Acute Caffeine Supplementation Improve Physical Performance in Female Team-Sport Athletes? Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alejandro Gomez-Bruton, Jorge Marin-Puyalto, Borja Muñiz-Pardos, Angel Matute-Llorente, Juan Del Coso, Alba Gomez-Cabello, German Vicente-Rodriguez, Jose A Casajus, Gabriel Lozano-Berges. Nutrients (2021)

Does Acute Caffeine Supplementation Improve Physical Performance in Female Team-Sport Athletes? Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alejandro Gomez-Bruton, Jorge Marin-Puyalto, Borja Muñiz-Pardos, Angel Matute-Llorente, Juan Del Coso, Alba Gomez-Cabello, German Vicente-Rodriguez, Jose A Casajus, Gabriel Lozano-Berges. Nutrients (2021)

Caffeinated Drinks and Physical Performance in Sport: A Systematic Review. Sergio L Jiménez, Javier Díaz-Lara, Helios Pareja-Galeano, Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2021)

Caffeinated Drinks and Physical Performance in Sport: A Systematic Review. Sergio L Jiménez, Javier Díaz-Lara, Helios Pareja-Galeano, Juan Del Coso. Nutrients (2021)

Ergogenic Effects of Acute Caffeine Intake on Muscular Endurance and Muscular Strength in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Grgic J, Del Coso J. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021)

Ergogenic Effects of Acute Caffeine Intake on Muscular Endurance and Muscular Strength in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Grgic J, Del Coso J. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021)

Is caffeine mouth rinsing an effective strategy to improve physical and cognitive performance? A systematic review. da Silva WF, Lopes-Silva JP, Camati Felippe LJ, Ferreira GA, Lima-Silva AE, Silva-Cavalcante MD. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Is caffeine mouth rinsing an effective strategy to improve physical and cognitive performance? A systematic review. da Silva WF, Lopes-Silva JP, Camati Felippe LJ, Ferreira GA, Lima-Silva AE, Silva-Cavalcante MD. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Caffeine and Cognitive Functions in Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lorenzo Calvo J, Fei X, Domínguez R, Pareja-Galeano H. Nutrients (2021)

Caffeine and Cognitive Functions in Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lorenzo Calvo J, Fei X, Domínguez R, Pareja-Galeano H. Nutrients (2021)

Nonplacebo Controls to Determine the Magnitude of Ergogenic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Marticorena FM, Carvalho A, de Oliveira LF, Dolan E, Gualano B, Swinton P, Saunders B. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2021)

Nonplacebo Controls to Determine the Magnitude of Ergogenic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Marticorena FM, Carvalho A, de Oliveira LF, Dolan E, Gualano B, Swinton P, Saunders B. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2021)

CYP1A2 genotype and acute ergogenic effects of caffeine intake on exercise performance: a systematic review. Grgic J, Pickering C, Del Coso J, Schoenfeld BJ, Mikulic P. Eur J Nutr (2021)

CYP1A2 genotype and acute ergogenic effects of caffeine intake on exercise performance: a systematic review. Grgic J, Pickering C, Del Coso J, Schoenfeld BJ, Mikulic P. Eur J Nutr (2021)

Effects of diet interventions, dietary supplements, and performance-enhancing substances on the performance of CrossFit-trained individuals: A systematic review of clinical studies. Dos Santos Quaresma MVL, Guazzelli Marques C, Nakamoto FP. Nutrition (2021)

Effects of diet interventions, dietary supplements, and performance-enhancing substances on the performance of CrossFit-trained individuals: A systematic review of clinical studies. Dos Santos Quaresma MVL, Guazzelli Marques C, Nakamoto FP. Nutrition (2021)

Effect of Acute Caffeine Intake on the Fat Oxidation Rate during Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Pérez AM, Merellano-Navarro E, Coso JD. Nutrients (2020)

Effect of Acute Caffeine Intake on the Fat Oxidation Rate during Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Collado-Mateo D, Lavín-Pérez AM, Merellano-Navarro E, Coso JD. Nutrients (2020)

Effect of Supplements on Endurance Exercise in the Older Population: Systematic Review. Martínez-Rodríguez A, Cuestas-Calero BJ, Hernández-García M, Martíez-Olcina M, Vicente-Martínez M, Rubio-Arias JÁ. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020)

Effect of Supplements on Endurance Exercise in the Older Population: Systematic Review. Martínez-Rodríguez A, Cuestas-Calero BJ, Hernández-García M, Martíez-Olcina M, Vicente-Martínez M, Rubio-Arias JÁ. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020)

The Effects of Caffeine Mouth Rinsing on Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Ehlert AM, Twiddy HM, Wilson PB. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2020)

The Effects of Caffeine Mouth Rinsing on Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Ehlert AM, Twiddy HM, Wilson PB. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2020)

Effects of caffeine supplementation on muscle endurance, maximum strength, and perceived exertion in adults submitted to strength training: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ferreira TT, da Silva JVF, Bueno NB. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

Effects of caffeine supplementation on muscle endurance, maximum strength, and perceived exertion in adults submitted to strength training: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ferreira TT, da Silva JVF, Bueno NB. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

Acute Effects of Caffeine Supplementation on Movement Velocity in Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Raya-González J, Rendo-Urteaga T, Domínguez R, Castillo D, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Grgic J. Sports Med (2020)

Acute Effects of Caffeine Supplementation on Movement Velocity in Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Raya-González J, Rendo-Urteaga T, Domínguez R, Castillo D, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Grgic J. Sports Med (2020)

The Effects of Caffeine Ingestion on Measures of Rowing Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Grgic J, Diaz-Lara FJ, Coso JD, Duncan MJ, Tallis J, Pickering C, Schoenfeld BJ, Mikulic P. Nutrients (2020)

The Effects of Caffeine Ingestion on Measures of Rowing Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Grgic J, Diaz-Lara FJ, Coso JD, Duncan MJ, Tallis J, Pickering C, Schoenfeld BJ, Mikulic P. Nutrients (2020)

Is Caffeine Recommended Before Exercise? A Systematic Review To Investigate Its Impact On Cardiac Autonomic Control Via Heart Rate And Its Variability. Benjamim CJR, Kliszczewicz B, Garner DM, Cavalcante TCF, da Silva AAM, Santana MDR, Valenti VE. J Am Coll Nutr (2020)

Is Caffeine Recommended Before Exercise? A Systematic Review To Investigate Its Impact On Cardiac Autonomic Control Via Heart Rate And Its Variability. Benjamim CJR, Kliszczewicz B, Garner DM, Cavalcante TCF, da Silva AAM, Santana MDR, Valenti VE. J Am Coll Nutr (2020)

Isolated effects of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate ingestion on performance in the Yo-Yo test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Grgic J, Garofolini A, Pickering C, Duncan MJ, Tinsley GM, Del Coso J. J Sci Med Sport (2020)

Isolated effects of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate ingestion on performance in the Yo-Yo test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Grgic J, Garofolini A, Pickering C, Duncan MJ, Tinsley GM, Del Coso J. J Sci Med Sport (2020)

Wake up and smell the coffee: caffeine supplementation and exercise performance-an umbrella review of 21 published meta-analyses. Grgic J, Grgic I, Pickering C, Schoenfeld BJ, Bishop DJ, Pedisic Z. Br J Sports Med (2020)

Wake up and smell the coffee: caffeine supplementation and exercise performance-an umbrella review of 21 published meta-analyses. Grgic J, Grgic I, Pickering C, Schoenfeld BJ, Bishop DJ, Pedisic Z. Br J Sports Med (2020)

Effect of Caffeine Supplementation on Sports Performance Based on Differences Between Sexes: A Systematic Review. Juan Mielgo-Ayuso, Diego Marques-Jiménez, Ignacio Refoyo, Juan Del Coso, Patxi León-Guereño, Julio Calleja-González. Nutrients (2019)

Effect of Caffeine Supplementation on Sports Performance Based on Differences Between Sexes: A Systematic Review. Juan Mielgo-Ayuso, Diego Marques-Jiménez, Ignacio Refoyo, Juan Del Coso, Patxi León-Guereño, Julio Calleja-González. Nutrients (2019)

The effects of caffeine ingestion on isokinetic muscular strength: A meta-analysis. Grgic J, Pickering C. J Sci Med Sport (2019)

The effects of caffeine ingestion on isokinetic muscular strength: A meta-analysis. Grgic J, Pickering C. J Sci Med Sport (2019)

Caffeine Supplementation and Physical Performance, Muscle Damage and Perception of Fatigue in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. Mielgo-Ayuso J, Calleja-Gonzalez J, Del Coso J, Urdampilleta A, León-Guereño P, Fernández-Lázaro D. Nutrients (2019)

Caffeine Supplementation and Physical Performance, Muscle Damage and Perception of Fatigue in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review. Mielgo-Ayuso J, Calleja-Gonzalez J, Del Coso J, Urdampilleta A, León-Guereño P, Fernández-Lázaro D. Nutrients (2019)

Effects of acute ingestion of caffeine on team sports performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Salinero JJ, Lara B, Del Coso J. Res Sports Med (2019)

Effects of acute ingestion of caffeine on team sports performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Salinero JJ, Lara B, Del Coso J. Res Sports Med (2019)

Correction to: The Effect of Acute Caffeine Ingestion on Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Southward K, Rutherfurd-Markwick KJ, Ali A. Sports Med (2018). Note: this article was originally published here but contained errors that were corrected in this revised version.

Correction to: The Effect of Acute Caffeine Ingestion on Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Southward K, Rutherfurd-Markwick KJ, Ali A. Sports Med (2018). Note: this article was originally published here but contained errors that were corrected in this revised version.

Effects of Coffee Components on Muscle Glycogen Recovery: A Systematic Review. Loureiro LMR, Reis CEG, da Costa THM. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2018)

Effects of Coffee Components on Muscle Glycogen Recovery: A Systematic Review. Loureiro LMR, Reis CEG, da Costa THM. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2018)

Caffeine and Physiological Responses to Submaximal Exercise: A Meta-Analysis. Glaister M, Gissane C. Int J Sports Physiol Perform (2018)

Caffeine and Physiological Responses to Submaximal Exercise: A Meta-Analysis. Glaister M, Gissane C. Int J Sports Physiol Perform (2018)

Caffeine ingestion enhances Wingate performance: a meta-analysis. Grgic J. Eur J Sport Sci (2018)

Caffeine ingestion enhances Wingate performance: a meta-analysis. Grgic J. Eur J Sport Sci (2018)

Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Ian Clark, Hans Peter Landolt. Sleep Med Rev (2017)

Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Ian Clark, Hans Peter Landolt. Sleep Med Rev (2017)

Acute effects of caffeine-containing energy drinks on physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Souza DB, Del Coso J, Casonatto J, Polito MD. Eur J Nutr (2017)

Acute effects of caffeine-containing energy drinks on physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Souza DB, Del Coso J, Casonatto J, Polito MD. Eur J Nutr (2017)

A systematic review of the efficacy of ergogenic aids for improving running performance. Schubert MM, Astorino TA. J Strength Cond Res (2013)

A systematic review of the efficacy of ergogenic aids for improving running performance. Schubert MM, Astorino TA. J Strength Cond Res (2013)

Does caffeine added to carbohydrate provide additional ergogenic benefit for endurance? Conger SA, Warren GL, Hardy MA, Millard-Stafford ML. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2011)

Does caffeine added to carbohydrate provide additional ergogenic benefit for endurance? Conger SA, Warren GL, Hardy MA, Millard-Stafford ML. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2011)

Efficacy of acute caffeine ingestion for short-term high-intensity exercise performance: a systematic review. Astorino TA, Roberson DW. J Strength Cond Res (2010)

Efficacy of acute caffeine ingestion for short-term high-intensity exercise performance: a systematic review. Astorino TA, Roberson DW. J Strength Cond Res (2010)

Effect of caffeine on sport-specific endurance performance: a systematic review. Ganio MS, Klau JF, Casa DJ, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. J Strength Cond Res (2009)

Effect of caffeine on sport-specific endurance performance: a systematic review. Ganio MS, Klau JF, Casa DJ, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. J Strength Cond Res (2009)

Effects of caffeine ingestion on rating of perceived exertion during and after exercise: a meta-analysis. Doherty M, Smith PM. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2005 )

Effects of caffeine ingestion on rating of perceived exertion during and after exercise: a meta-analysis. Doherty M, Smith PM. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2005 )

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Stay educated. Be informed.

Stay educated. Be informed.

Strengthen the fight for Clean Sport:

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

And remember:

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Photo of pyramid by Eugene Tkachenko on Unsplash.

Some amino acids are coded by our genes, some are used to build proteins; others are not. Taurine is an amino acid produced in the body from the metabolism of the amino acid, cysteine, but it is not used as a “building block” for protein synthesis. Instead, it interacts with ion channels to stabilize cell membrane integrity and regulate osmoregulation (water transport). Taurine is also essential for cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle function. See Lambert et al. 2014 to read all about the physiology of taurine from one of my former colleagues in Copenhagen.

Besides producing taurine in the body, we also obtain taurine in our diet, primarily from meat, dairy, seafood, and algae-containing food, like seaweed (see here and here). Because taurine regulates calcium homeostasis and can increase calcium-binding proteins during muscle contraction, it is alleged to play a role in muscle strength and endurance. Therefore, taurine is the stimulant of choice in many “energy” drinks (e.g. RedBull). But…

Does taurine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Does taurine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

To conclude…

This tool is free. Please help keep it alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. Want free info like this in your inbox? Sign up here:

Full list of systematic reviews examining taurine for performance.

Here is the list of systematic reviews I have summarised above.

The Dose Response of Taurine on Aerobic and Strength Exercises: A Systematic Review. Chen Q, Li Z, Pinho RA, Gupta RC, Ugbolue UC, Thirupathi A, Gu Y. Front Physiol (2021).

The Dose Response of Taurine on Aerobic and Strength Exercises: A Systematic Review. Chen Q, Li Z, Pinho RA, Gupta RC, Ugbolue UC, Thirupathi A, Gu Y. Front Physiol (2021).

The Effects of an Oral Taurine Dose and Supplementation Period on Endurance Exercise Performance in Humans: A Meta-Analysis. Mark Waldron, Stephen David Patterson, Jamie Tallent, Owen Jeffries. Sports Med (2018)

The Effects of an Oral Taurine Dose and Supplementation Period on Endurance Exercise Performance in Humans: A Meta-Analysis. Mark Waldron, Stephen David Patterson, Jamie Tallent, Owen Jeffries. Sports Med (2018)

Acute effects of caffeine-containing energy drinks on physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diego B Souza, Juan Del Coso, Juliano Casonatto, Marcos D Polito. Eur J Nutr (2017)

Acute effects of caffeine-containing energy drinks on physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diego B Souza, Juan Del Coso, Juliano Casonatto, Marcos D Polito. Eur J Nutr (2017)

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Stay educated. Be informed.

Stay educated. Be informed.

Strengthen the fight for Clean Sport:

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

And remember:

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Photo of pyramid by Eugene Tkachenko on Unsplash.

Some amino acids are coded by our genes, some are used to build proteins; others are not. Creatine is a naturally occurring amino acid derivative but, unlike standard amino acids, it is not coded by our genes and it is not a protein building block. Instead, creatine is involved in energy metabolism. In humans, the vast majority (~95%) of creatine is found in our muscles. Our body can synthesise creatine from the amino acids, arginine and glycine, but because creatine is also degraded to creatinine and then excreted in our urine, we must also consume creatine in our diet to maintain adequate bodily levels. This can be achieved by eating meat (inc. red meat, chicken, pork, etc), fish (e.g. salmon) and seafood.

ATP hydrolysis: ATP → ADP + Pi + H+

ATP resynthesis: PCr → Cr + Pi then ADP + Pi → ATP

So, by having adequate muscle levels of creatine, you have the opportunity to produce phosphocreatine. Therefore, the creatine in your muscles helps maintain ATP availability for maximal-effort, anaerobic/sprint-type exercise. Since daily creatine supplementation increases its levels in your muscles, creatine has become a very popular supplement. So…

ATP resynthesis: PCr → Cr + Pi then ADP + Pi → ATP

Does creatine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Does creatine improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

To conclude…

This tool is free. Please help keep it alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. Want free info like this in your inbox? Sign up here:

Full list of systematic reviews examining creatine for performance.

Here is the list of systematic reviews I have summarised above.

The Effects of Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training on Regional Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ryan Burke, Alec Piñero, Max Coleman, Adam Mohan, Max Sapuppo, Francesca Augustin, Alan A Aragon, Darren G Candow, Scott C Forbes, Paul Swinton, Brad J Schoenfeld. Nutrients (2023)

The Effects of Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training on Regional Measures of Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ryan Burke, Alec Piñero, Max Coleman, Adam Mohan, Max Sapuppo, Francesca Augustin, Alan A Aragon, Darren G Candow, Scott C Forbes, Paul Swinton, Brad J Schoenfeld. Nutrients (2023)

Effects of Creatine Monohydrate on Endurance Performance in a Trained Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Julen Fernández-Landa, Asier Santibañez-Gutierrez, Nikola Todorovic, Valdemar Stajer, Sergej M Ostojic. Sports Med (2023)

Effects of Creatine Monohydrate on Endurance Performance in a Trained Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Julen Fernández-Landa, Asier Santibañez-Gutierrez, Nikola Todorovic, Valdemar Stajer, Sergej M Ostojic. Sports Med (2023)

Effectiveness of Creatine in Metabolic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arturo P Jaramillo, Luisa Jaramillo, Javier Castells, Andres Beltran, Neyla Garzon Mora, Sol Torres, Gabriela Carolina Barberan Parraga, Maria P Vallejo, Yurianna Santos. Cureus (2023)

Effectiveness of Creatine in Metabolic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arturo P Jaramillo, Luisa Jaramillo, Javier Castells, Andres Beltran, Neyla Garzon Mora, Sol Torres, Gabriela Carolina Barberan Parraga, Maria P Vallejo, Yurianna Santos. Cureus (2023)

Short-Term Creatine Supplementation and Repeated Sprint Ability-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mark Glaister, Lauren Rhodes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Short-Term Creatine Supplementation and Repeated Sprint Ability-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mark Glaister, Lauren Rhodes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Efficacy of Alternative Forms of Creatine Supplementation on Improving Performance and Body Composition in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review. Carly Fazio, Craig L Elder, Margaret M Harris. J Strength Cond Res (2022)

Efficacy of Alternative Forms of Creatine Supplementation on Improving Performance and Body Composition in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review. Carly Fazio, Craig L Elder, Margaret M Harris. J Strength Cond Res (2022)

The Paradoxical Effect of Creatine Monohydrate on Muscle Damage Markers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kenji Doma, Akhilesh Kumar Ramachandran, Daniel Boullosa & Jonathan Connor. Sports Med (2022)

The Paradoxical Effect of Creatine Monohydrate on Muscle Damage Markers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kenji Doma, Akhilesh Kumar Ramachandran, Daniel Boullosa & Jonathan Connor. Sports Med (2022)

Interaction Between Caffeine and Creatine When Used as Concurrent Ergogenic Supplements: A Systematic Review. Sara Elosegui, Jaime López-Seoane, María Martínez-Ferrán, Helios Pareja-Galeano. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Interaction Between Caffeine and Creatine When Used as Concurrent Ergogenic Supplements: A Systematic Review. Sara Elosegui, Jaime López-Seoane, María Martínez-Ferrán, Helios Pareja-Galeano. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2022)

Effects of creatine and caffeine ingestion in combination on exercise performance: A systematic review. Alisson H Marinho, Jaqueline S Gonçalves, Palloma K Araújo, Adriano E Lima-Silva, Thays Ataide-Silva, Gustavo G de Araujo. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Effects of creatine and caffeine ingestion in combination on exercise performance: A systematic review. Alisson H Marinho, Jaqueline S Gonçalves, Palloma K Araújo, Adriano E Lima-Silva, Thays Ataide-Silva, Gustavo G de Araujo. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Creatine supplementation and VO2 max: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Damien Gras, Charlotte Lanhers, Reza Bagheri, Fred Dutheil. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Creatine supplementation and VO2 max: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Damien Gras, Charlotte Lanhers, Reza Bagheri, Fred Dutheil. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

The Effect of Creatine Supplementation on Markers of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Intervention Trials. Northeast B, Clifford T. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2021)

The Effect of Creatine Supplementation on Markers of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Intervention Trials. Northeast B, Clifford T. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2021)

Benefits of Creatine Supplementation for Vegetarians Compared to Omnivorous Athletes: A Systematic Review. Kaviani M, Shaw K, Chilibeck PD. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020)

Benefits of Creatine Supplementation for Vegetarians Compared to Omnivorous Athletes: A Systematic Review. Kaviani M, Shaw K, Chilibeck PD. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020)

The Additive Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Exercise Training in an Aging Population: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Stares A, Bains M. J Geriatr Phys Ther (2020)

The Additive Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Exercise Training in an Aging Population: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Stares A, Bains M. J Geriatr Phys Ther (2020)

Effect of the Combination of Creatine Monohydrate Plus HMB Supplementation on Sports Performance, Body Composition, Markers of Muscle Damage and Hormone Status: A Systematic Review. Fernández-Landa J, Calleja-González J, León-Guereño P, Caballero-García A, Córdova A, Mielgo-Ayuso J. Nutrients (2019)

Effect of the Combination of Creatine Monohydrate Plus HMB Supplementation on Sports Performance, Body Composition, Markers of Muscle Damage and Hormone Status: A Systematic Review. Fernández-Landa J, Calleja-González J, León-Guereño P, Caballero-García A, Córdova A, Mielgo-Ayuso J. Nutrients (2019)

Effects of Creatine Supplementation on Athletic Performance in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mielgo-Ayuso J, Calleja-Gonzalez J, Marqués-Jiménez D, Caballero-García A, Córdova A, Fernández-Lázaro D. Nutrients (2019)

Effects of Creatine Supplementation on Athletic Performance in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mielgo-Ayuso J, Calleja-Gonzalez J, Marqués-Jiménez D, Caballero-García A, Córdova A, Fernández-Lázaro D. Nutrients (2019)

Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Konstantinos I Avgerinos, Nikolaos Spyrou, Konstantinos I Bougioukas, Dimitrios Kapogiannis. Exp Gerontol (2018)

Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Konstantinos I Avgerinos, Nikolaos Spyrou, Konstantinos I Bougioukas, Dimitrios Kapogiannis. Exp Gerontol (2018)

Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Sports Med (2017)

Creatine Supplementation and Upper Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Sports Med (2017)

Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Sports Med (2015)

Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Sports Med (2015)

Creatine supplementation and aging musculoskeletal health. Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Forbes SC. Endocrine (2014)

Creatine supplementation and aging musculoskeletal health. Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Forbes SC. Endocrine (2014)

Creatine supplementation during resistance training in older adults-a meta-analysis. Devries MC, Phillips SM. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2014)

Creatine supplementation during resistance training in older adults-a meta-analysis. Devries MC, Phillips SM. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2014)

Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Branch JD. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2003)

Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Branch JD. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2003)

Does oral creatine supplementation improve strength? A meta-analysis. Dempsey RL, Mazzone MF, Meurer LN. J Fam Pract (2002)

Does oral creatine supplementation improve strength? A meta-analysis. Dempsey RL, Mazzone MF, Meurer LN. J Fam Pract (2002)

Creatine supplementation as an ergogenic aid for sports performance in highly trained athletes: a critical review. Mujika I, Padilla S. Int J Sports Med (1997)

Creatine supplementation as an ergogenic aid for sports performance in highly trained athletes: a critical review. Mujika I, Padilla S. Int J Sports Med (1997)

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Stay educated. Be informed.

Stay educated. Be informed.

Strengthen the fight for Clean Sport:

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

And remember:

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Photo of pyramid by Eugene Tkachenko on Unsplash.

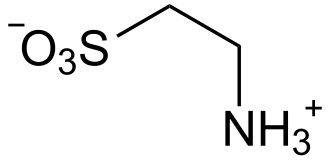

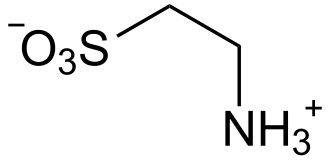

Nitrate (NO3-) is a naturally occurring ion found in high amounts in leafy green veg, like spinach, and in beetroot, which is the food that has been popularised when talking “nitrate”. When we ingest nitrate or nitrate-containing foods, nitrate (NO3-) is converted to nitrite (NO2-). Nitrite is then absorbed in the intestine into the blood and metabolised to produce nitric oxide (NO) via several different enzymatic pathways. And, nitric oxide is important because it plays a major role in the regulation of vascular (it increases blood flow and vasodilation, which may enhance the delivery of oxygen and energy substrates to muscles) and metabolic (mitochondrial) function. But, it has a very short half-life in the body — when nitric oxide is produced, it acts rapidly and is used very quickly.

But, it’s little more complicated than than because we have no biological machinary to reduce nitrate (NO3-) to nitrite (NO2-) and rely on bacteria in our mouth for this part of the process (these bacteria use an enzyme called nitrate reductase to provide an electron and a proton to catalyse this reaction):

NO3- + e- + H+ → NO2- + H2O

Nitrate + an Electron + a Proton → Nitrite + Water

Interestingly, since it is the bacteria in your mouth that convert nitrate to nitrite allowing your biology to produce nitric oxide (NO), an alcohol-based mouthwash can prevent you producing nitrite (and, therefore, nitric oxide) after eating nitrate (see here & here)… Oh NO.

Nitrate + an Electron + a Proton → Nitrite + Water

Nitric oxide can be synthesised in our body from the amino acid, L-arginine, by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes. So, dietary intake of nitrate provides an additional source of nitric oxide on top of what our nitric oxide synthase pathways can produce. Since nitric oxide regulates blood flow and mitochondrial function, you can see why ingesting nitrate or nitrate-containing foods may be of interest to an athlete. But, nitrate (or beetroot) is certainly one of those compounds for which it is easy to head to PubMed and cherry-pick a paper showing that it is or is not beneficial for sports performance. So…

Does nitrate (or beetroot) improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Does nitrate (or beetroot) improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Effects on Strength and power:

Effects on Endurance:

All that said, there are also several nuances in this field:

To conclude…

This tool is free. Please help keep it alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. Want free info like this in your inbox? Sign up here:

Full list of systematic reviews examining nitrate and beetroot for performance.

Here is the list of systematic reviews I have summarised above.

Effects of dietary inorganic nitrate on blood pressure during and post exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Benjamim et al. (2024) Free Radic Biol Med

Effects of dietary inorganic nitrate on blood pressure during and post exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Benjamim et al. (2024) Free Radic Biol Med

Does Beetroot Supplementation Improve Performance in Combat Sports Athletes? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Delleli et al. (2023) Nutrients

Does Beetroot Supplementation Improve Performance in Combat Sports Athletes? A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Delleli et al. (2023) Nutrients

Limited Effects of Inorganic Nitrate Supplementation on Exercise Training Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Hogwood et al. (2023) Sports Med Open

Limited Effects of Inorganic Nitrate Supplementation on Exercise Training Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Hogwood et al. (2023) Sports Med Open

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Back Squat and Bench Press Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tan et al. (2023) Nutrients

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Back Squat and Bench Press Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tan et al. (2023) Nutrients

Effects of Beetroot-Based Supplements on Muscular Endurance and Strength in Healthy Male Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evangelista et al. (2023) JANA

Effects of Beetroot-Based Supplements on Muscular Endurance and Strength in Healthy Male Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evangelista et al. (2023) JANA

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Performance during Single and Repeated Bouts of Short-Duration High-Intensity Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Alsharif et al. (2023) Antioxidants

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Performance during Single and Repeated Bouts of Short-Duration High-Intensity Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Alsharif et al. (2023) Antioxidants

Factors that Moderate the Effect of Nitrate Ingestion on Exercise Performance in Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions. Silva et al. (2022) Adv Nutr

Factors that Moderate the Effect of Nitrate Ingestion on Exercise Performance in Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions. Silva et al. (2022) Adv Nutr

Dietary Inorganic Nitrate as an Ergogenic Aid: An Expert Consensus Derived via the Modified Delphi Technique. Shannon et al. (2022) Sports Med

Dietary Inorganic Nitrate as an Ergogenic Aid: An Expert Consensus Derived via the Modified Delphi Technique. Shannon et al. (2022) Sports Med

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate on the Contractile Properties of Human Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ozcan Esen, Nick Dobbin, Michael J Callaghan. J Am Nutr Assoc (2022)

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate on the Contractile Properties of Human Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ozcan Esen, Nick Dobbin, Michael J Callaghan. J Am Nutr Assoc (2022)

The Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Explosive Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Rachel Tan,Leire Cano, Ángel Lago-Rodríguez and Raúl Domínguez. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022)

The Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Explosive Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Rachel Tan,Leire Cano, Ángel Lago-Rodríguez and Raúl Domínguez. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022)

The Effect of Beetroot Ingestion on High-Intensity Interval Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tak Hiong Wong, Alexiaa Sim, Stephen F Burns. Nutrients (2021)

The Effect of Beetroot Ingestion on High-Intensity Interval Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tak Hiong Wong, Alexiaa Sim, Stephen F Burns. Nutrients (2021)

Effect of food sources of nitrate, polyphenols, L-arginine and L-citrulline on endurance exercise performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Noah M. A. d’Unienville, Henry T. Blake, Alison M. Coates, Alison M. Hill, Maximillian J. Nelson & Jonathan D. Buckley. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

Effect of food sources of nitrate, polyphenols, L-arginine and L-citrulline on endurance exercise performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Noah M. A. d’Unienville, Henry T. Blake, Alison M. Coates, Alison M. Hill, Maximillian J. Nelson & Jonathan D. Buckley. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

Effect of dietary nitrate on human muscle power: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Coggan AR, Baranauskas MN, Hinrichs RJ, Liu Z, Carter SJ. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

Effect of dietary nitrate on human muscle power: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Coggan AR, Baranauskas MN, Hinrichs RJ, Liu Z, Carter SJ. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

Effects of Beetroot Supplementation on Recovery After Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review. Rojano-Ortega D, Peña Amaro J, Berral-Aguilar AJ, Berral-de la Rosa FJ. Sports Health (2021)

Effects of Beetroot Supplementation on Recovery After Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review. Rojano-Ortega D, Peña Amaro J, Berral-Aguilar AJ, Berral-de la Rosa FJ. Sports Health (2021)

The effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance and cardiorespiratory measures in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gao C, Gupta S, Adli T, Hou W, Coolsaet R, Hayes A, Kim K, Pandey A, Gordon J, Chahil G, Belley-Cote EP, Whitlock RP. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

The effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on endurance exercise performance and cardiorespiratory measures in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gao C, Gupta S, Adli T, Hou W, Coolsaet R, Hayes A, Kim K, Pandey A, Gordon J, Chahil G, Belley-Cote EP, Whitlock RP. J Int Soc Sports Nutr (2021)

The Effect of Nitrate-Rich Beetroot Juice on Markers of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Intervention Trials. Jones L, Bailey SJ, Rowland SN, Alsharif N, Shannon OM, Clifford T. < J Diet Suppl (2021)

The Effect of Nitrate-Rich Beetroot Juice on Markers of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Intervention Trials. Jones L, Bailey SJ, Rowland SN, Alsharif N, Shannon OM, Clifford T. < J Diet Suppl (2021)

Effect of dietary nitrate ingestion on muscular performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alvares TS, Oliveira GV, Volino-Souza M, Conte-Junior CA, Murias JM. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Effect of dietary nitrate ingestion on muscular performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alvares TS, Oliveira GV, Volino-Souza M, Conte-Junior CA, Murias JM. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2021)

Ergogenic potential of foods for performance and recovery: a new alternative in sports supplementation? A systematic review. Costa MS, Toscano LT, Toscano LLT, Luna VR, Torres RA, Silva JA, Silva AS. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

Ergogenic potential of foods for performance and recovery: a new alternative in sports supplementation? A systematic review. Costa MS, Toscano LT, Toscano LLT, Luna VR, Torres RA, Silva JA, Silva AS. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Isokinetic Torque in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.. Lago-Rodríguez Á, Domínguez R, Ramos-Álvarez JJ, Tobal FM, Jodra P, Tan R, Bailey SJ. Nutrients (2020)

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Isokinetic Torque in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.. Lago-Rodríguez Á, Domínguez R, Ramos-Álvarez JJ, Tobal FM, Jodra P, Tan R, Bailey SJ. Nutrients (2020)

Ergogenic Effect of Nitrate Supplementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Senefeld JW, Wiggins CC, Regimbal RJ, Dominelli PB, Baker SE, Joyner MJ. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2020)

Ergogenic Effect of Nitrate Supplementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Senefeld JW, Wiggins CC, Regimbal RJ, Dominelli PB, Baker SE, Joyner MJ. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2020)

Nutritional Ergogenic Aids in Racquet Sports: A Systematic Review. Vicente-Salar N, Santos-Sánchez G, Roche E. Nutrients (2020)

Nutritional Ergogenic Aids in Racquet Sports: A Systematic Review. Vicente-Salar N, Santos-Sánchez G, Roche E. Nutrients (2020)

Effects of Dietary Nitrates on Time Trial Performance in Athletes with Different Training Status: Systematic Review. Hlinský T, Kumstát M, Vajda P. Nutrients (2020)

Effects of Dietary Nitrates on Time Trial Performance in Athletes with Different Training Status: Systematic Review. Hlinský T, Kumstát M, Vajda P. Nutrients (2020)

Effects of diet interventions, dietary supplements, and performance-enhancing substances on the performance of CrossFit-trained individuals: A systematic review of clinical studies. Dos Santos Quaresma MVL, Guazzelli Marques C, Nakamoto FP. Nutrition (2021)

Effects of diet interventions, dietary supplements, and performance-enhancing substances on the performance of CrossFit-trained individuals: A systematic review of clinical studies. Dos Santos Quaresma MVL, Guazzelli Marques C, Nakamoto FP. Nutrition (2021)

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Weightlifting Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. San Juan AF, Dominguez R, Lago-Rodríguez Á, Montoya JJ, Tan R, Bailey SJ. Nutriients (2020)

Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Weightlifting Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. San Juan AF, Dominguez R, Lago-Rodríguez Á, Montoya JJ, Tan R, Bailey SJ. Nutriients (2020)

Effectiveness of beetroot juice derived nitrates supplementation on fatigue resistance during repeated-sprints: a systematic review. Rojas-Valverde D, Montoya-Rodríguez J, Azofeifa-Mora C, Sanchez-Urena B. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

Effectiveness of beetroot juice derived nitrates supplementation on fatigue resistance during repeated-sprints: a systematic review. Rojas-Valverde D, Montoya-Rodríguez J, Azofeifa-Mora C, Sanchez-Urena B. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (2020)

Influence of Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Cyclic Sports Performance: A Systematic Review. Lorenzo Calvo J, Alorda-Capo F, Pareja-Galeano H, Jiménez SL. Nutrients (2020)

Influence of Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Cyclic Sports Performance: A Systematic Review. Lorenzo Calvo J, Alorda-Capo F, Pareja-Galeano H, Jiménez SL. Nutrients (2020)

Nutritional Strategies to Optimize Performance and Recovery in Rowing Athletes. Kim J, Kim EK. Nutrients (2020)

Nutritional Strategies to Optimize Performance and Recovery in Rowing Athletes. Kim J, Kim EK. Nutrients (2020)

The Effect of Nitrate Supplementation on Exercise Tolerance and Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Van De Walle GP, Vukovich MD. J Strength Cond Res (2018)

The Effect of Nitrate Supplementation on Exercise Tolerance and Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Van De Walle GP, Vukovich MD. J Strength Cond Res (2018)

Nitrate supplementation improves physical performance specifically in non-athletes during prolonged open-ended tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Campos HO, Drummond LR, Rodrigues QT, Machado FSM, Pires W, Wanner SP, Coimbra CC. Br J Nutr (2018)

Nitrate supplementation improves physical performance specifically in non-athletes during prolonged open-ended tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Campos HO, Drummond LR, Rodrigues QT, Machado FSM, Pires W, Wanner SP, Coimbra CC. Br J Nutr (2018)

Performance and Health Benefits of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Stanaway L, Rutherfurd-Markwick K, Page R, Ali A. Nutrients (2017)

Performance and Health Benefits of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Stanaway L, Rutherfurd-Markwick K, Page R, Ali A. Nutrients (2017)

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. McMahon NF, Leveritt MD, Pavey TG. Sports Med (2017)

The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. McMahon NF, Leveritt MD, Pavey TG. Sports Med (2017)

Effects of Beetroot Juice Supplementation on Cardiorespiratory Endurance in Athletes. A Systematic Review. Domínguez R, Cuenca E, Maté-Muñoz JL, García-Fernández P, Serra-Paya N, Estevan MC, Herreros PV, Garnacho-Castaño MV. Nutrients (2017)

Effects of Beetroot Juice Supplementation on Cardiorespiratory Endurance in Athletes. A Systematic Review. Domínguez R, Cuenca E, Maté-Muñoz JL, García-Fernández P, Serra-Paya N, Estevan MC, Herreros PV, Garnacho-Castaño MV. Nutrients (2017)

The effect of nitrate supplementation on exercise performance in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hoon MW, Johnson NA, Chapman PG, Burke LM. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2013)

The effect of nitrate supplementation on exercise performance in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hoon MW, Johnson NA, Chapman PG, Burke LM. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (2013)

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

You are the only person responsible for what goes in your body.

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Ignorance is not an excuse!

Stay educated. Be informed.

Stay educated. Be informed.

Strengthen the fight for Clean Sport:

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Consult WADA’s prohibited list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Cross-check your meds against the Global DRO drug reference list.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

Only choose supplements that have been independently tested.

And remember:

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Nail your daily nutrition habits first, layer specific sports nutrition on top of that, and then start to consider supplements.

Photo of pyramid by Eugene Tkachenko on Unsplash.

Some amino acids are coded by our genes, some are used to build proteins; others are not. Citrulline is an amino acid that is not coded by our genes and is not a protein building block but it is a “nonessential” amino acid (i.e. our body can synthesise it and we don’t need to consume it). Citrulline is an intermediate metabolite of the urea cycle produced in the mitochondria of the liver (see here for description of urea cycle and a diagram here). Citrulline is also synthesised from arginine by the enzyme, nitric oxide synthase, during nitric oxide (NO) production.

2 L-arginine + 3 NADPH + 3 H+ + 4 O2 ⇌ 2 L-citrulline + 2 nitric oxide + 4 H2O + 3 NADP+

Although our bodies naturally produce citrulline, consuming citrulline or citrulline-containing foods increases our citrulline levels. Citrulline is found in high amounts in watermelon, therefore citrulline-containing supplements include watermelon juice but also pure L-citrulline and citrulline malate. Malate is an intermediate metabolite of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (a process that helps you produce ATP in the mitochondria). Therefore, supplement Lords believe malate will increase ATP production. Whether this is true is currently unknown and the effect of citrulline malate vs. L-citrulline is also not known.

In the context of exercise, the mechanistic effects of citrulline are not well understood. Based on cell studies, animal studies, and some human data, citrulline is thought to increase levels of nitric oxide (NO), a molecule that regulates mitochondrial and vascular function (increased blood flow and vasodilation to enhance the delivery of oxygen) with rapid but very short-lived effects. Meanwhile, due to its role in the urea cycle, citrulline may also improve the clearance of ammonia (which can accumulate in muscle during intense exercise and cause fatigue). Whether such potential mechanisms extrapolate to an improvement in performance is why I am writing this. So…

Does Citrulline (or watermelon juice or citrulline malate) improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

Does Citrulline (or watermelon juice or citrulline malate) improve performance — what do the systematic reviews say?

To conclude…

This tool is free. Please help keep it alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer. Want free info like this in your inbox? Sign up here:

Full list of systematic reviews examining citrulline (malate) and watermelon for performance.

Here is the list of systematic reviews I have summarised above.

Effects of citrulline on endurance performance in young healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harnden et al. (2023) J Int Soc Sports Nutr