The running science “nerd alert”

from Thomas Solomon PhD

December 2022

Each month we compile a short list of recently-published papers (full list here) in the world of running science and break them into bite-sized chunks so you can digest them as food for thought to help optimise your training. To help wash it all down, we even review our favourite beer of the month.

Welcome to this month's instalment of our “Nerd Alert”. We hope you enjoy it.

Welcome to this month's instalment of our “Nerd Alert”. We hope you enjoy it.

Click the title of each article to reveal our summary.

Full paper access: click here

What is the hypothesis or research question?

What is the hypothesis or research question?

Strength training is known to improve running economy and performance, but the comparative effectiveness of different types of strength training is unknown. Therefore, the authors completed a systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine whether there are different effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training on running economy and running time trial performance in trained runners.

What do the authors do to test the hypothesis or answer the research question?

What do the authors do to test the hypothesis or answer the research question?

— The authors completed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effects of heavy resistance training or plyometric training on running economy and/or running performance in healthy runners.

— Plyometric training studies included exercises that utilised the stretch-shortening cycle with body weight or an external load set at <20% 1-rep max (1RM) exercise, versus no plyometric training.

— Heavy resistance training studies included exercises with an external load set at ≥70% of 1RM or its equivalent (≤12 RM), versus no heavy resistance training.

— The systematic review included studies with training interventions lasting at least 4 weeks, studies of trained middle or long-distance runners, and studies in which the primary outcome was running economy and/or running time trial performance.

— Hedges’ g effect size estimates were calculated and compiled in two separate meta-analyses to determine a summary effect size for each type of training.

— The authors then compared the results of the two meta-analyses to determine whether heavy resistance training or plyometric training was more effective. But, despite the title of the paper and the authors’ stated aim of the study, the effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training are not compared statistically.

— The authors also completed additional subgroups analyses to determine the influence of age, length of intervention, runner type, performance level, moderate vs. heavy resistance training, etc.

What do they find?

What do they find?

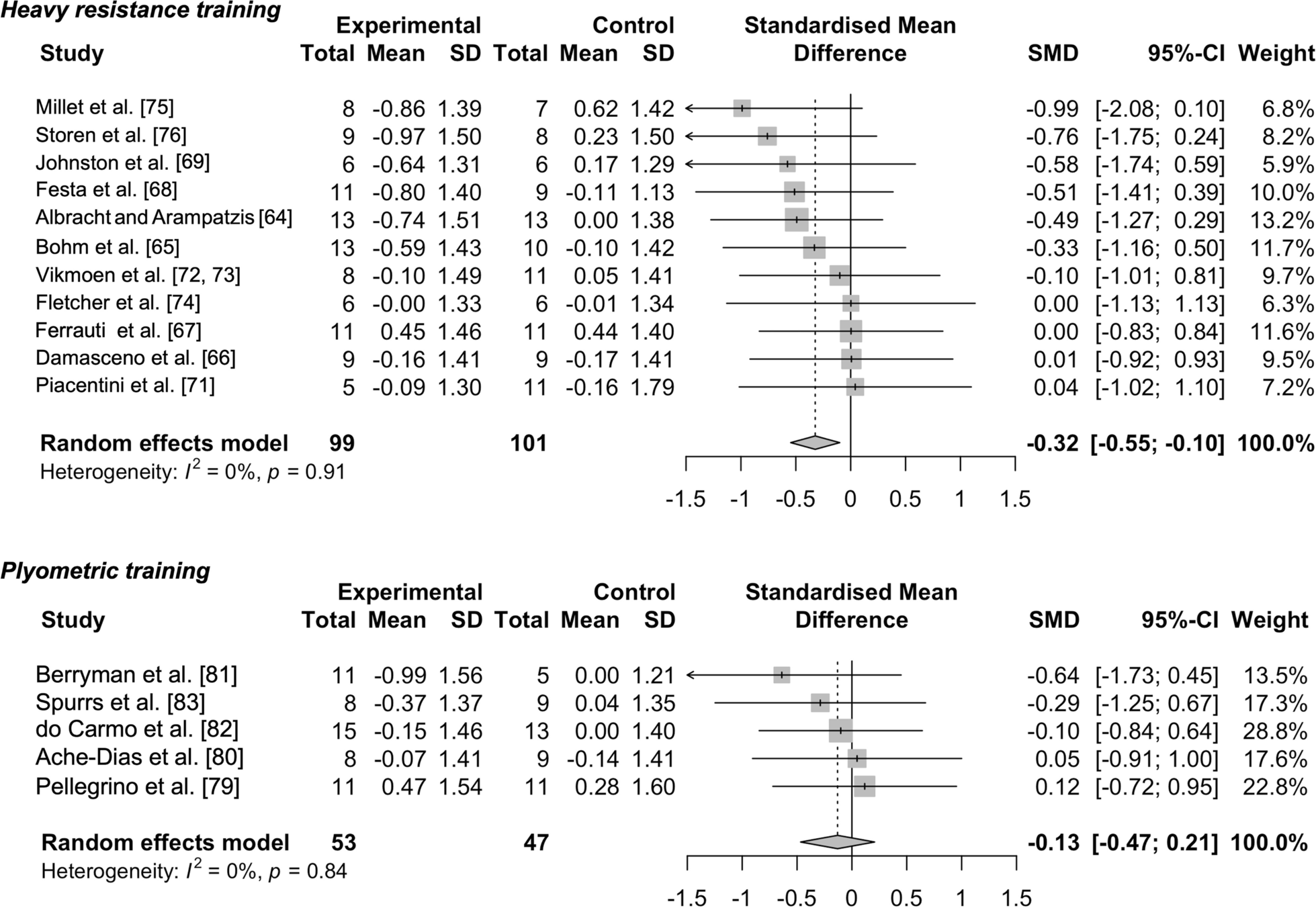

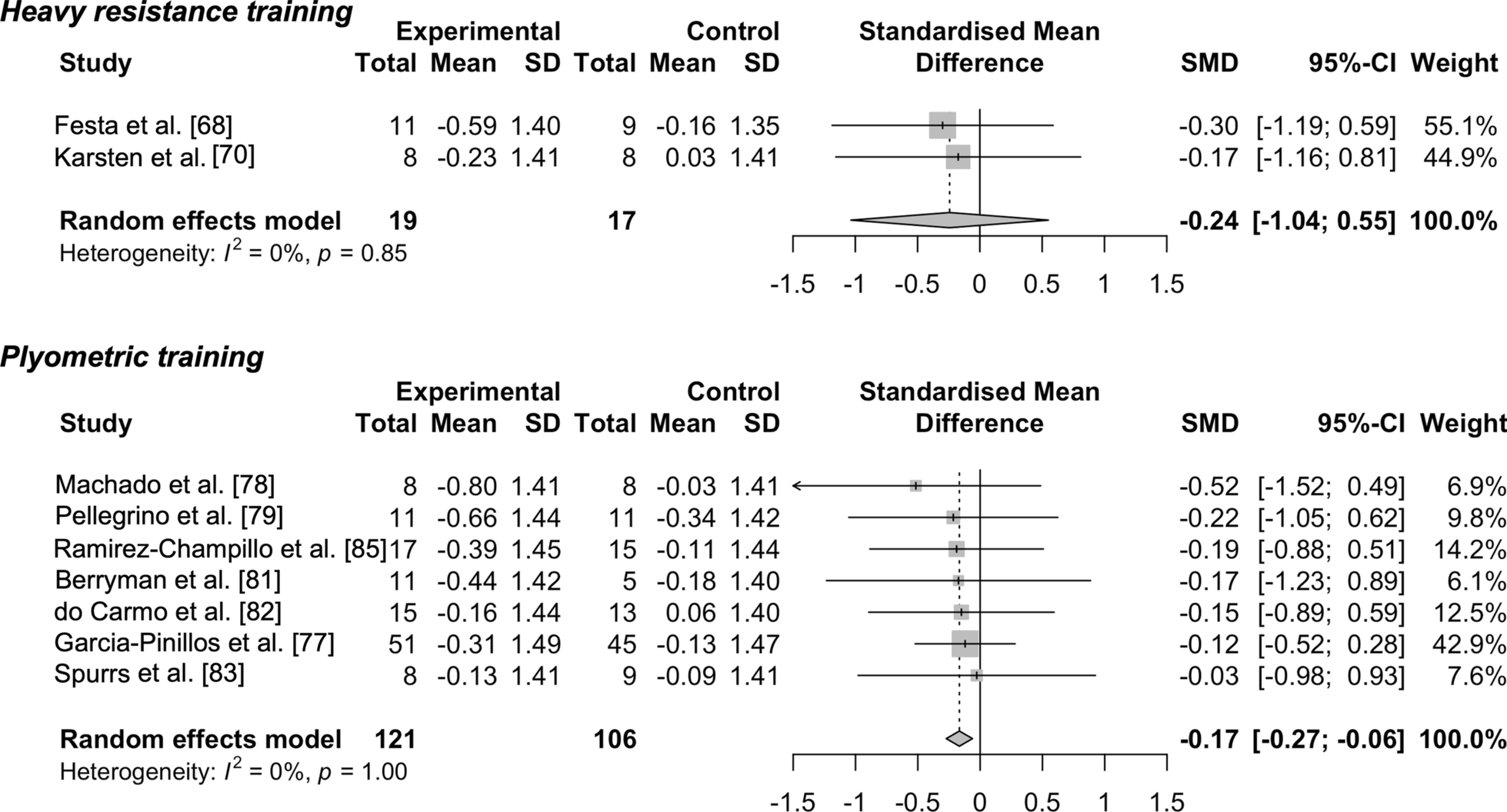

— Twenty-two studies were included in the systematic review. Eleven studies of heavy resistance training (99 subjects in the intervention group; 101 subjects in the control group) and 5 studies of plyometric training (53 intervention; 47 control) measured running economy while 2 studies of heavy resistance training (19 subjects in the intervention group; 17 subjects in the control group) and 7 studies of plyometric training (121 intervention; 106 control) measured running time trial performance.

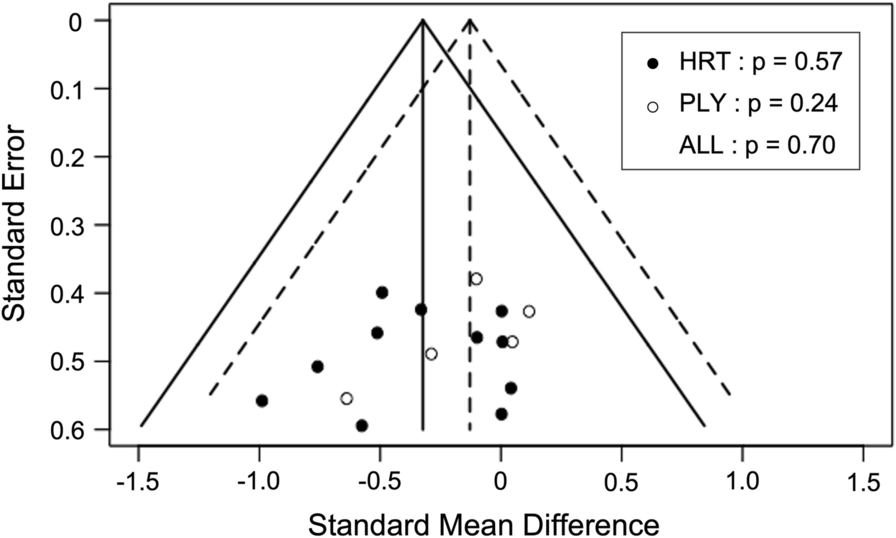

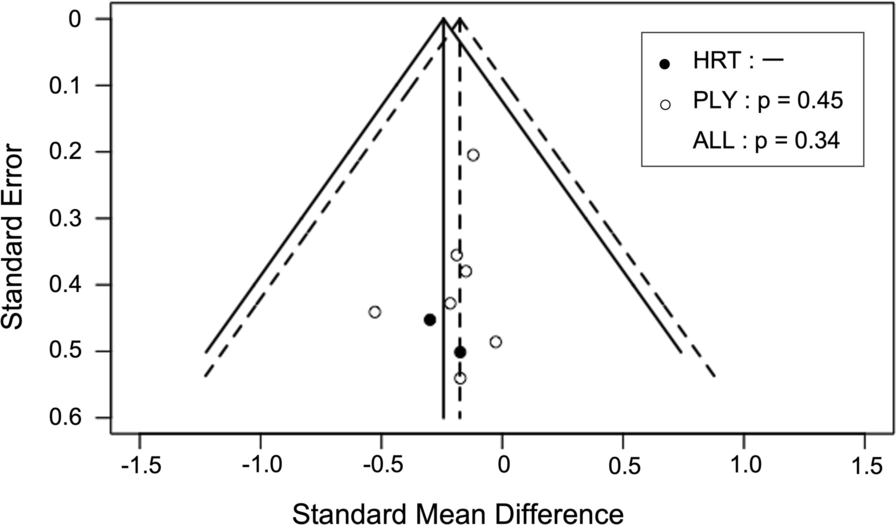

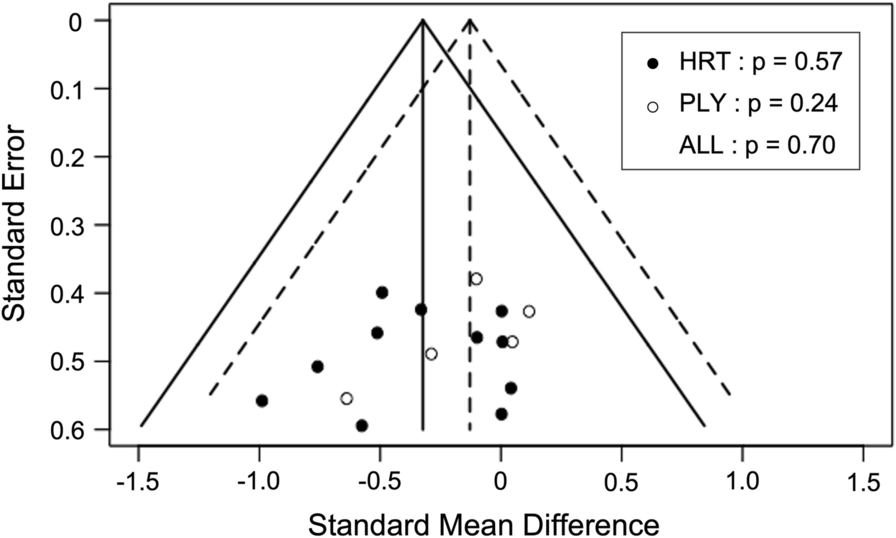

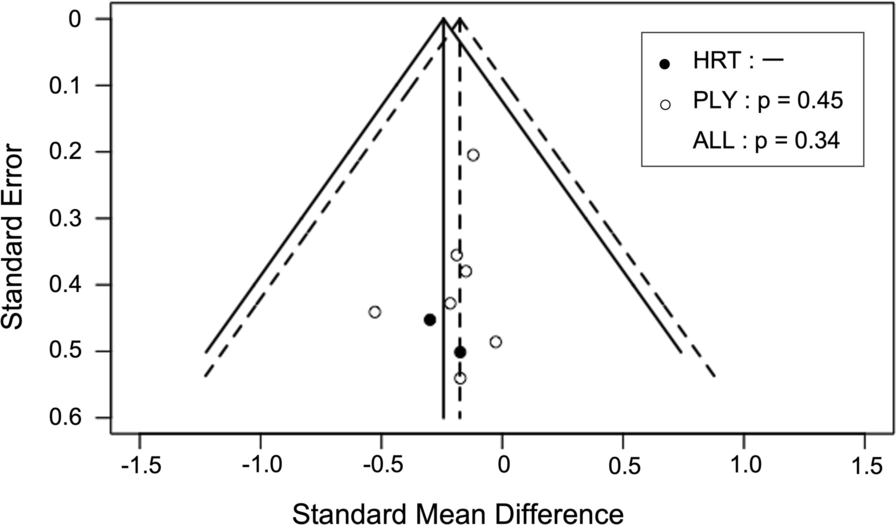

— Risk of bias was deemed acceptable, funnel plots (see below) indicated a low risk of publication bias, and no significant heterogeneity (variability) was found among the studies.

Funnel plots of the studies that examined the effects on running economy. The plot of heavy resistance training (HRT) is shown as a solid line; that for plyometric training (PLY) is represented as a dash line. Egger’s tests were performed for HRT, PLY, and all plots (ALL).

Funnel plots of the studies that examined the effects on running time trial performance. [Legend] The plot of heavy resistance training (HRT) is shown as a solid line; that for plyometric training (PLY) is represented as a dash line. Egger’s tests were performed for HRT, PLY, and all plots (ALL).

Effect on running economy:

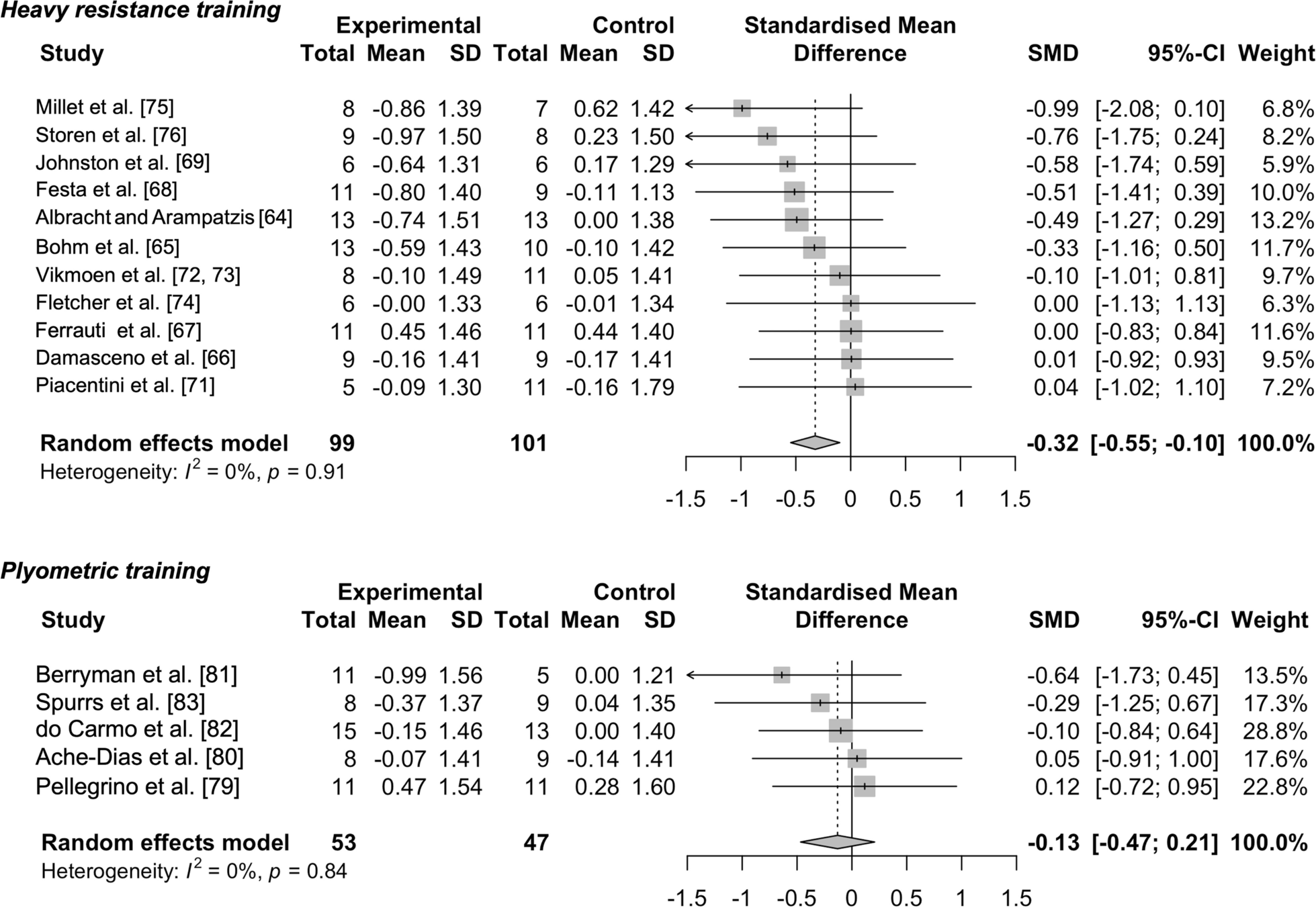

— Heavy resistance training caused a small improvement in running economy (effect size = -0.32; 95% confidence interval = -0.55 to -0.10; see the forest plot below for a full analysis). Subgroup analysis showed that this benefit was greater with heavier resistance exercise (at least 90% of 1RM or a load that can be lifted for only 4-reps or less) and with interventions lasting at least 10 weeks (see Table 4 in paper).

— Plyometrics training had a trivial (effect size = -0.13) and likely meaningless (large confidence interval overlapping zero; 95% CI = -0.47 to +0.21) effect on running economy. See the forest plot below for a full analysis.

Forest plots of effects of heavy resistance and plyometric training on running economy. Each plot consists of standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% CIs. A negative value in SMD represents beneficial effects following heavy resistance or plyometric training as an adjunct to running training, while a positive value in SMD indicates detrimental effects.

Effect on running time trial performance:

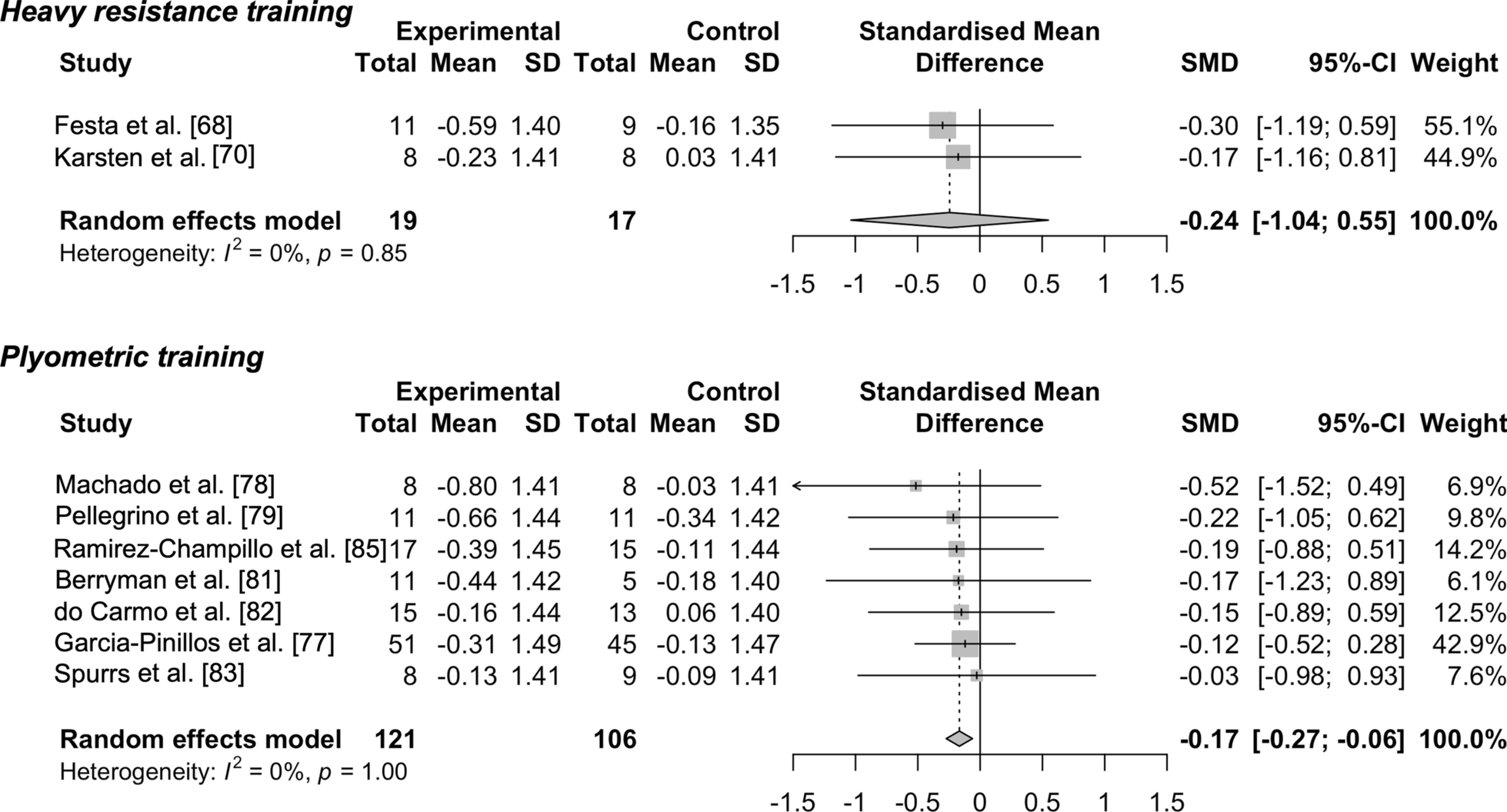

— Heavy resistance training had a small (effect size = -0.24) but likely meaningless (large confidence interval overlapping zero; 95% confidence interval = -1.04 to +0.55) benefit on running time trial performance. See the forest plot below for a full analysis.

— Plyometrics training caused a trivial improvement in running time trial performance (effect size = -0.17, 95% CI = -0.27 to -0.06; details in forest plot below).

Forest plots of effects of heavy resistance and plyometric training on running time trial performance. Each plot consists of standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% CIs. A negative value in SMD represents beneficial effects following heavy resistance or plyometric training as an adjunct to running training, while a positive value in SMD indicates detrimental effects.

Comparison of interventions:

— For running economy, the pooled effect size for heavy resistance training was greater than that for plyometric training: a small effect size for heavy resistance training (Hedges’ g = − 0.32) vs. a trivial effect size for plyometric training (Hedges’ g = − 0.17), with the 95% confidence interval (CI) of heavy resistance training not crossing zero, indicating a meaningful effect of heavy resistance training but not plyometric training on running economy.

— For running time trial performance, the pooled effect size was also larger for heavy resistance training vs. plyometric training (g = -0.24 [i.e. small] vs. -0.17 [i.e trivial]), but the 95% CI of heavy resistance training crossed zero, indicating a meaningful effect of plyometric training but not heavy resistance training on running performance.

— However, heavy strength training and plyometric training were not directly compared using statistical methods. Despite that, the authors concluded that adding heavy resistance training to existing running training would more effectively improve running economy and running time trial performance than adding plyometric training and that such benefits are greatest with heavy resistance training (at least 90% of 1-rep max) for at least 10 weeks. As discussed in the “What are the weaknesses?” section below, we dispute the validity of that conclusion.

What are the strengths?

What are the strengths?

— The review aims to address an important question that could help endurance runners (and coaches) design more effective training programs.

— The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Study quality and risk of bias were assessed and reported using standard tools, and funnel plots were presented to help illustrate publication bias (aka, the predominance of only positive findings being published and, therefore, available for analysis). Effect sizes were presented in a forest plot with a random-effects model to help illustrate between-study variability.

— The data tables and Figures are clearly presented and the authors note the limitations of their analyses.

What are the weaknesses?

What are the weaknesses?

— The authors did not pre-register the systematic review protocol before beginning the study, so we cannot know if the original aim of the review, or its analyses, changed during the synthesis of the review.

— Neither the raw data nor the statistical code (from R Studio) are made available.

— Running economy is defined as the metabolic cost (energy expenditure in kiloJoules) or oxygen cost (V̇O2) required to cover a given distance (kilometres) or to maintain a given speed (kph) at a submaximal speed. Therefore, it is measured and reported in several ways. It is unclear how the authors dealt with the different versions of running economy measurements reported among studies.

— Despite the title of the paper (“Heavy Resistance Training Versus Plyometric Training”) and the authors’ stated aim of the study, the effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training are not compared using statistical methods. The differences are simply inferred from the data.

— The authors conclude that “Heavy resistance training as an adjunct to running training would be more effective in improving running economy and running time trial performance than plyometric training”. However, the authors ignore their findings that the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect size for the effect of heavy resistance training on running time trial performance crosses zero, indicating that this effect is not meaningful. Since the 95% CI for the trivial effect size of plyometric training does not cross zero, it is possible to interpret the data in a different way, i.e. that “Heavy resistance training as an adjunct to running training would be more effective in improving running economy than plyometric training but plyometric training would be more effective in improving running time trial performance”. These alternate interpretations indicate the presence of bias in the meta-analysis, aka meta-bias. Because only a small number of studies (2 heavy resistance and 7 plyometric training) measured running time trial performance, more data (more randomised controlled trials) are needed before we can have confidence in the current meta-analytical outcomes — when more studies are published, the meta-analysis will be updated and the truth will be revealed.

Are the findings useful in application to training/coaching practice?

Are the findings useful in application to training/coaching practice?

Kinda…

We already know that running economy is one of the main determinants of endurance performance, therefore it is important to understand which interventions can improve it. But an improvement in running economy does not necessarily mean an improvement in running performance. Since an athlete’s ultimate goal is to improve their race day performance, it is more important to understand which interventions improve running performance rather than economy.

From prior work, the evidence is already pretty clear that strength training of some kind is a good investment for runners — existing systematic reviews show that strength training can improve economy (see here and here) and endurance performance (see here, here, here, here, here, & here) in endurance athletes. This new systematic review was supposed to compare heavy resistance vs. plyometric training to see which is a better use of time, but the authors did not make this important direct comparison using statistical methods. We can infer from the results that heavy lifting might outperform plyometric training for improving running economy. But, due to a lack of included studies for heavy resistance training, it is not possible to make accurate inferences about whether heavy lifting or plyometrics is best for improving running time trial performance. In general, we will continue to recommend that runners should strength train.

What is our Rating of Perceived Scientific Enjoyment?

What is our Rating of Perceived Scientific Enjoyment?

RP(s)E = 5 out of 10.

Strength training is known to improve running economy and performance, but the comparative effectiveness of different types of strength training is unknown. Therefore, the authors completed a systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine whether there are different effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training on running economy and running time trial performance in trained runners.

— The authors completed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effects of heavy resistance training or plyometric training on running economy and/or running performance in healthy runners.

— Plyometric training studies included exercises that utilised the stretch-shortening cycle with body weight or an external load set at <20% 1-rep max (1RM) exercise, versus no plyometric training.

— Heavy resistance training studies included exercises with an external load set at ≥70% of 1RM or its equivalent (≤12 RM), versus no heavy resistance training.

— The systematic review included studies with training interventions lasting at least 4 weeks, studies of trained middle or long-distance runners, and studies in which the primary outcome was running economy and/or running time trial performance.

— Hedges’ g effect size estimates were calculated and compiled in two separate meta-analyses to determine a summary effect size for each type of training.

— The authors then compared the results of the two meta-analyses to determine whether heavy resistance training or plyometric training was more effective. But, despite the title of the paper and the authors’ stated aim of the study, the effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training are not compared statistically.

— The authors also completed additional subgroups analyses to determine the influence of age, length of intervention, runner type, performance level, moderate vs. heavy resistance training, etc.

— Twenty-two studies were included in the systematic review. Eleven studies of heavy resistance training (99 subjects in the intervention group; 101 subjects in the control group) and 5 studies of plyometric training (53 intervention; 47 control) measured running economy while 2 studies of heavy resistance training (19 subjects in the intervention group; 17 subjects in the control group) and 7 studies of plyometric training (121 intervention; 106 control) measured running time trial performance.

— Risk of bias was deemed acceptable, funnel plots (see below) indicated a low risk of publication bias, and no significant heterogeneity (variability) was found among the studies.

Effect on running economy:

— Heavy resistance training caused a small improvement in running economy (effect size = -0.32; 95% confidence interval = -0.55 to -0.10; see the forest plot below for a full analysis). Subgroup analysis showed that this benefit was greater with heavier resistance exercise (at least 90% of 1RM or a load that can be lifted for only 4-reps or less) and with interventions lasting at least 10 weeks (see Table 4 in paper).

— Plyometrics training had a trivial (effect size = -0.13) and likely meaningless (large confidence interval overlapping zero; 95% CI = -0.47 to +0.21) effect on running economy. See the forest plot below for a full analysis.

Effect on running time trial performance:

— Heavy resistance training had a small (effect size = -0.24) but likely meaningless (large confidence interval overlapping zero; 95% confidence interval = -1.04 to +0.55) benefit on running time trial performance. See the forest plot below for a full analysis.

— Plyometrics training caused a trivial improvement in running time trial performance (effect size = -0.17, 95% CI = -0.27 to -0.06; details in forest plot below).

Comparison of interventions:

— For running economy, the pooled effect size for heavy resistance training was greater than that for plyometric training: a small effect size for heavy resistance training (Hedges’ g = − 0.32) vs. a trivial effect size for plyometric training (Hedges’ g = − 0.17), with the 95% confidence interval (CI) of heavy resistance training not crossing zero, indicating a meaningful effect of heavy resistance training but not plyometric training on running economy.

— For running time trial performance, the pooled effect size was also larger for heavy resistance training vs. plyometric training (g = -0.24 [i.e. small] vs. -0.17 [i.e trivial]), but the 95% CI of heavy resistance training crossed zero, indicating a meaningful effect of plyometric training but not heavy resistance training on running performance.

— However, heavy strength training and plyometric training were not directly compared using statistical methods. Despite that, the authors concluded that adding heavy resistance training to existing running training would more effectively improve running economy and running time trial performance than adding plyometric training and that such benefits are greatest with heavy resistance training (at least 90% of 1-rep max) for at least 10 weeks. As discussed in the “What are the weaknesses?” section below, we dispute the validity of that conclusion.

— The review aims to address an important question that could help endurance runners (and coaches) design more effective training programs.

— The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Study quality and risk of bias were assessed and reported using standard tools, and funnel plots were presented to help illustrate publication bias (aka, the predominance of only positive findings being published and, therefore, available for analysis). Effect sizes were presented in a forest plot with a random-effects model to help illustrate between-study variability.

— The data tables and Figures are clearly presented and the authors note the limitations of their analyses.

— The authors did not pre-register the systematic review protocol before beginning the study, so we cannot know if the original aim of the review, or its analyses, changed during the synthesis of the review.

— Neither the raw data nor the statistical code (from R Studio) are made available.

— Running economy is defined as the metabolic cost (energy expenditure in kiloJoules) or oxygen cost (V̇O2) required to cover a given distance (kilometres) or to maintain a given speed (kph) at a submaximal speed. Therefore, it is measured and reported in several ways. It is unclear how the authors dealt with the different versions of running economy measurements reported among studies.

— Despite the title of the paper (“Heavy Resistance Training Versus Plyometric Training”) and the authors’ stated aim of the study, the effects of heavy resistance training and plyometric training are not compared using statistical methods. The differences are simply inferred from the data.

— The authors conclude that “Heavy resistance training as an adjunct to running training would be more effective in improving running economy and running time trial performance than plyometric training”. However, the authors ignore their findings that the 95% confidence interval of the pooled effect size for the effect of heavy resistance training on running time trial performance crosses zero, indicating that this effect is not meaningful. Since the 95% CI for the trivial effect size of plyometric training does not cross zero, it is possible to interpret the data in a different way, i.e. that “Heavy resistance training as an adjunct to running training would be more effective in improving running economy than plyometric training but plyometric training would be more effective in improving running time trial performance”. These alternate interpretations indicate the presence of bias in the meta-analysis, aka meta-bias. Because only a small number of studies (2 heavy resistance and 7 plyometric training) measured running time trial performance, more data (more randomised controlled trials) are needed before we can have confidence in the current meta-analytical outcomes — when more studies are published, the meta-analysis will be updated and the truth will be revealed.

Kinda…

We already know that running economy is one of the main determinants of endurance performance, therefore it is important to understand which interventions can improve it. But an improvement in running economy does not necessarily mean an improvement in running performance. Since an athlete’s ultimate goal is to improve their race day performance, it is more important to understand which interventions improve running performance rather than economy.

From prior work, the evidence is already pretty clear that strength training of some kind is a good investment for runners — existing systematic reviews show that strength training can improve economy (see here and here) and endurance performance (see here, here, here, here, here, & here) in endurance athletes. This new systematic review was supposed to compare heavy resistance vs. plyometric training to see which is a better use of time, but the authors did not make this important direct comparison using statistical methods. We can infer from the results that heavy lifting might outperform plyometric training for improving running economy. But, due to a lack of included studies for heavy resistance training, it is not possible to make accurate inferences about whether heavy lifting or plyometrics is best for improving running time trial performance. In general, we will continue to recommend that runners should strength train.

RP(s)E = 5 out of 10.

That is all for this month's nerd alert. We hope to have succeeded in helping you learn a little more about the developments in the world of running science. If not, we hope you enjoyed a nice beer…

If you find value in our nerd alerts, please help keep them alive by sharing them on social media and buying us a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join Thomas @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to Thomas’s free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out Thomas’s other articles, nerd alerts, free training tools, and his Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to Thomas’s articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Until next month, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be...

If you find value in our nerd alerts, please help keep them alive by sharing them on social media and buying us a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join Thomas @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to Thomas’s free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out Thomas’s other articles, nerd alerts, free training tools, and his Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to Thomas’s articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Until next month, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be...

Every day is a school day.

Empower yourself to train smart.

Think critically. Be informed. Stay educated.

Empower yourself to train smart.

Think critically. Be informed. Stay educated.

Disclaimer: We occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that we are not sponsored by or receiving advertisement royalties from anyone. We have conducted biomedical research for which we have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies. We have also advised and consulted for private companies on their product developments. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of our work. Any recommendations we make are, and always will be, based on our own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. The information we provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information we provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in these nerd-alerts, please help keep them alive and buy us a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

If you enjoy this free content, please like and follow @thomaspjsolomon and @veohtu and share these posts on your social media pages.

About the authors:

Matt and Thomas are both passionate about making science accessible and helping folks meet their fitness and performance goals. They both have PhDs in exercise science, are widely published, have had their own athletic careers, and are both performance coaches alongside their day jobs. Originally from different sides of the Atlantic, their paths first crossed in Copenhagen in 2010 as research scientists at the Centre for Inflammation and Metabolism at Rigshospitalet (Copenhagen University Hospital). After discussing lots of science, spending many a mile pounding the trails, and frequent micro brew pub drinking sessions, they became firm friends. Thomas even got a "buy one get one free" deal out of the friendship, marrying one of Matt's best friends from home after a chance encounter during a training weekend for the CCC in Schwartzwald. Although they are once again separated by the Atlantic, Matt and Thomas meet up about once a year and have weekly video chats about science, running, and beer. This "nerd alert" was created as an outlet for some of thehundreds of scientific papers craft beers they read drink each month.

Matt and Thomas are both passionate about making science accessible and helping folks meet their fitness and performance goals. They both have PhDs in exercise science, are widely published, have had their own athletic careers, and are both performance coaches alongside their day jobs. Originally from different sides of the Atlantic, their paths first crossed in Copenhagen in 2010 as research scientists at the Centre for Inflammation and Metabolism at Rigshospitalet (Copenhagen University Hospital). After discussing lots of science, spending many a mile pounding the trails, and frequent micro brew pub drinking sessions, they became firm friends. Thomas even got a "buy one get one free" deal out of the friendship, marrying one of Matt's best friends from home after a chance encounter during a training weekend for the CCC in Schwartzwald. Although they are once again separated by the Atlantic, Matt and Thomas meet up about once a year and have weekly video chats about science, running, and beer. This "nerd alert" was created as an outlet for some of the

To read more about the authors, click the buttons:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

Copyright © Thomas Solomon and Matt Laye. All rights reserved.