The running science “nerd alert”

from Thomas Solomon PhD

October 2022

Each month we compile a short list of recently-published papers (full list here) in the world of running science and break them into bite-sized chunks so you can digest them as food for thought to help optimise your training. To help wash it all down, we even review our favourite beer of the month.

Welcome to this month's instalment of our “Nerd Alert”. We hope you enjoy it.

Welcome to this month's instalment of our “Nerd Alert”. We hope you enjoy it.

Click the title of each article to reveal our summary.

Full paper access: click here

What is the hypothesis or research question?

What is the hypothesis or research question?

Injuries are common in runners. Running-related injuries typically affect the lower limb because of overuse and include medial tibial stress syndrome (aka “shin splints”), Achilles tendinopathy, and patellofemoral pain. Changing step rate (aka cadence) is a commonly used approach to prevent and/or treat injuries. But, the scientific basis for doing so is unclear. The authors of this paper aimed to understand the effect of changing running step rates on injury, performance, and biomechanics.

What do the authors do to test the hypothesis or answer the research question?

What do the authors do to test the hypothesis or answer the research question?

— The authors conducted a systematic review to determine the effects of changes in step rate (aka cadence) on injury and performance (primary outcomes) and lower-limb biomechanics (second outcome).

— Thirty-seven studies met their inclusion criteria: 36 studies examined biomechanics but only 2 studies examined injury risk and only 5 others studied performance metrics.

— Standardised mean differences with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the variables of interest to estimate an effect size for each included study. But, no overall summary effect sizes were calculated; i.e. the authors did not do an actual meta-analysis.

What do they find?

What do they find?

— A lot… and yet not that much...

— Almost all of the studies examined the short-term (approx 4 to 12 weeks) effects of changing step rate.

— The two studies on injury risk showed very limited support that increased step rate reduced patellofemoral pain.

— The five studies on performance showed no effect of increasing or decreasing step rate vs. subjects’ preferred rate on oxygen consumption (V̇O2) or running economy, while increasing step rate lowered ratings of perceived exertion (RPE; effect size = -0.49; 95%CI -0.91 to -0.07) and feelings of effort (effect size = -0.69; 95% CI -1.34 to -0.03) in 1 study.

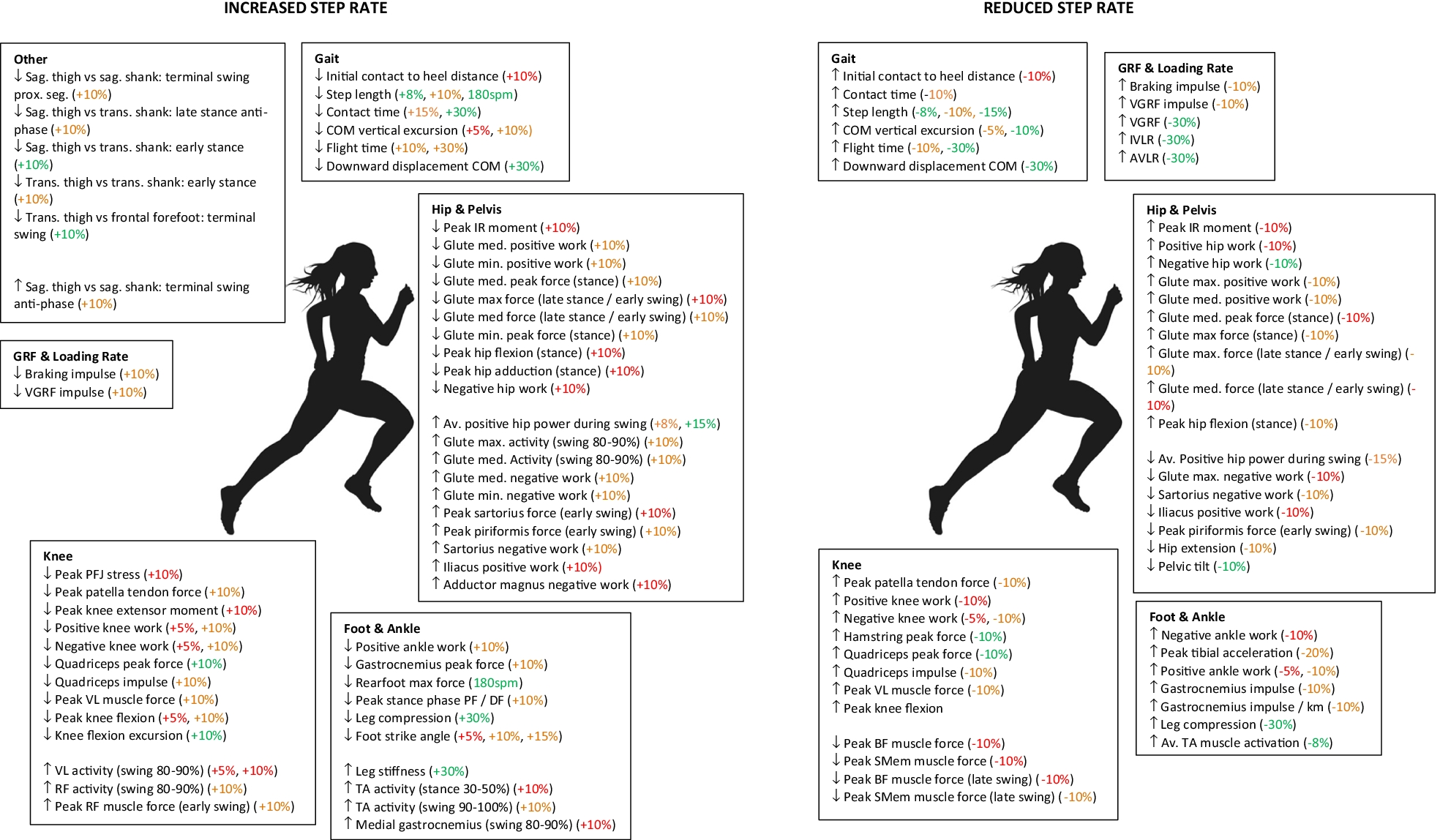

— The main biomechanical changes when the step rate was increased or decreased are summarized in the following image. The main takeaway is that knee flexion does seem to decrease when the step rate is increased from the subjects’ preferred frequency. Furthermore, while the ground impact force may decrease for each gait cycle when step rate is increased, the total load during an entire run is not likely to change because increasing step rate makes a runner take more total steps.

Image Copyright © Anderson et al (2022). Used under open access Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

What are the strengths?

What are the strengths?

— The paper aims to address an important topic that causes much confusion among athletes and coaches.

-- The protocol was prospectively registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews. The published paper adhered to the protocol without amendments or deviations. br> — The methods clearly describe how the systematic review was synthesised and the review follows best practice guidelines.

— The authors included ALL data in the paper — there are several pages of tables — the authors are fully-transparent.

What are the weaknesses?

What are the weaknesses?

— In general, all of the included studies had the following weaknesses:

— The methods do not make it clear what type of study designs were planned for inclusion. For example, was this a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (the best type) or a review of any repeated measures or cross-sectional study including those without a control group (weaker)? As we find out in the results (see Table 1), of the 37 papers included in the systematic review, only 3 were randomised controlled trials while the remainders were non-randomised cross-sectional studies or case-control studies.

— None of the included studies actually measured performance, i.e. changes in time trial time, time-to-exhaustion at a fixed intensity, or race performance. Instead, they measured surrogate markers such as V̇O2, RPE, and “awkwardness” (which we have no idea what that means).

— The data in the many tables are not presented in a visual way, for example with a forest plot that would help readers see the spread of data among studies. But, due to the lack of studies, summary effect sizes could not be calculated for most variables — more studies are needed.

— Due to the lack of summary effect sizes, the paper does not actually include a meta-analysis, contrary to the title of the paper. More future studies will eventually allow for a real meta-analysis.

Are the findings useful in application to training/coaching practice?

Are the findings useful in application to training/coaching practice?

Yes.

In the grunge-filled 1990s, during our high school running careers, both Matt and I received coaching instructions to run at 180 steps per minute because “this is the most efficient way to run” (quoting the words from Thomas’s high school coach). Hmmm. No doubt, you’ve come across this rule of thumb. Where did it come from? No clue. Should you listen to it? Hell no.

The current evidence does not support nor refute the idea of changing running step rate (aka cadence) as a means to improve performance or lower injury risk. Many more high-quality studies are needed to make a conclusion but these studies are tricky to do. That said, step rate is a common and reliable metric spat out from any GPS watch nowadays. Therefore, longer-term studies may become more feasible and questions related to performance and injury could be better studied. But for now, it’s hard to say either way whether changing your natural stride rate will have any meaningful impact.

What is our Rating of Perceived Scientific Enjoyment?

What is our Rating of Perceived Scientific Enjoyment?

RP(s)E = 7 out of 10.

Injuries are common in runners. Running-related injuries typically affect the lower limb because of overuse and include medial tibial stress syndrome (aka “shin splints”), Achilles tendinopathy, and patellofemoral pain. Changing step rate (aka cadence) is a commonly used approach to prevent and/or treat injuries. But, the scientific basis for doing so is unclear. The authors of this paper aimed to understand the effect of changing running step rates on injury, performance, and biomechanics.

— The authors conducted a systematic review to determine the effects of changes in step rate (aka cadence) on injury and performance (primary outcomes) and lower-limb biomechanics (second outcome).

— Thirty-seven studies met their inclusion criteria: 36 studies examined biomechanics but only 2 studies examined injury risk and only 5 others studied performance metrics.

— Standardised mean differences with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the variables of interest to estimate an effect size for each included study. But, no overall summary effect sizes were calculated; i.e. the authors did not do an actual meta-analysis.

— A lot… and yet not that much...

— Almost all of the studies examined the short-term (approx 4 to 12 weeks) effects of changing step rate.

— The two studies on injury risk showed very limited support that increased step rate reduced patellofemoral pain.

— The five studies on performance showed no effect of increasing or decreasing step rate vs. subjects’ preferred rate on oxygen consumption (V̇O2) or running economy, while increasing step rate lowered ratings of perceived exertion (RPE; effect size = -0.49; 95%CI -0.91 to -0.07) and feelings of effort (effect size = -0.69; 95% CI -1.34 to -0.03) in 1 study.

— The main biomechanical changes when the step rate was increased or decreased are summarized in the following image. The main takeaway is that knee flexion does seem to decrease when the step rate is increased from the subjects’ preferred frequency. Furthermore, while the ground impact force may decrease for each gait cycle when step rate is increased, the total load during an entire run is not likely to change because increasing step rate makes a runner take more total steps.

×

![]()

— The paper aims to address an important topic that causes much confusion among athletes and coaches.

-- The protocol was prospectively registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews. The published paper adhered to the protocol without amendments or deviations. br> — The methods clearly describe how the systematic review was synthesised and the review follows best practice guidelines.

— The authors included ALL data in the paper — there are several pages of tables — the authors are fully-transparent.

— In general, all of the included studies had the following weaknesses:

1. They were short-duration (only 4 to 12-weeks).

2. They do not focus on injury or performance.

3. They mostly include young uninjured athletes.

4. They’re limited to changing step rates rather than a combination of approaches to alter biomechanics under the guidance of clinicians and/or coaches.

— The methods do not make it clear what type of subjects were planned for inclusion. For example, trained runners, recreational/sub-elite/elite runners, or any folks? 2. They do not focus on injury or performance.

3. They mostly include young uninjured athletes.

4. They’re limited to changing step rates rather than a combination of approaches to alter biomechanics under the guidance of clinicians and/or coaches.

— The methods do not make it clear what type of study designs were planned for inclusion. For example, was this a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (the best type) or a review of any repeated measures or cross-sectional study including those without a control group (weaker)? As we find out in the results (see Table 1), of the 37 papers included in the systematic review, only 3 were randomised controlled trials while the remainders were non-randomised cross-sectional studies or case-control studies.

— None of the included studies actually measured performance, i.e. changes in time trial time, time-to-exhaustion at a fixed intensity, or race performance. Instead, they measured surrogate markers such as V̇O2, RPE, and “awkwardness” (which we have no idea what that means).

— The data in the many tables are not presented in a visual way, for example with a forest plot that would help readers see the spread of data among studies. But, due to the lack of studies, summary effect sizes could not be calculated for most variables — more studies are needed.

— Due to the lack of summary effect sizes, the paper does not actually include a meta-analysis, contrary to the title of the paper. More future studies will eventually allow for a real meta-analysis.

Yes.

In the grunge-filled 1990s, during our high school running careers, both Matt and I received coaching instructions to run at 180 steps per minute because “this is the most efficient way to run” (quoting the words from Thomas’s high school coach). Hmmm. No doubt, you’ve come across this rule of thumb. Where did it come from? No clue. Should you listen to it? Hell no.

The current evidence does not support nor refute the idea of changing running step rate (aka cadence) as a means to improve performance or lower injury risk. Many more high-quality studies are needed to make a conclusion but these studies are tricky to do. That said, step rate is a common and reliable metric spat out from any GPS watch nowadays. Therefore, longer-term studies may become more feasible and questions related to performance and injury could be better studied. But for now, it’s hard to say either way whether changing your natural stride rate will have any meaningful impact.

RP(s)E = 7 out of 10.

That is all for this month's nerd alert. We hope to have succeeded in helping you learn a little more about the developments in the world of running science. If not, we hope you enjoyed a nice beer…

If you find value in our nerd alerts, please help keep them alive by sharing them on social media and buying us a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join Thomas @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to Thomas’s free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out Thomas’s other articles, nerd alerts, free training tools, and his Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to Thomas’s articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Until next month, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be...

If you find value in our nerd alerts, please help keep them alive by sharing them on social media and buying us a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join Thomas @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to Thomas’s free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out Thomas’s other articles, nerd alerts, free training tools, and his Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to Thomas’s articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Until next month, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be...

Every day is a school day.

Empower yourself to train smart.

Think critically. Be informed. Stay educated.

Empower yourself to train smart.

Think critically. Be informed. Stay educated.

Disclaimer: We occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that we are not sponsored by or receiving advertisement royalties from anyone. We have conducted biomedical research for which we have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies. We have also advised private companies on their product developments. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of our work. Any recommendations we make are, and always will be, based on our own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. The information we provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information we provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in these nerd-alerts, please help keep them alive and buy us a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

If you enjoy this free content, please like and follow @thomaspjsolomon and @veohtu and share these posts on your social media pages.

About the authors:

Matt and Thomas are both passionate about making science accessible and helping folks meet their fitness and performance goals. They both have PhDs in exercise science, are widely published, have had their own athletic careers, and are both performance coaches alongside their day jobs. Originally from different sides of the Atlantic, their paths first crossed in Copenhagen in 2010 as research scientists at the Centre for Inflammation and Metabolism at Rigshospitalet (Copenhagen University Hospital). After discussing lots of science, spending many a mile pounding the trails, and frequent micro brew pub drinking sessions, they became firm friends. Thomas even got a "buy one get one free" deal out of the friendship, marrying one of Matt's best friends from home after a chance encounter during a training weekend for the CCC in Schwartzwald. Although they are once again separated by the Atlantic, Matt and Thomas meet up about once a year and have weekly video chats about science, running, and beer. This "nerd alert" was created as an outlet for some of thehundreds of scientific papers craft beers they read drink each month.

Matt and Thomas are both passionate about making science accessible and helping folks meet their fitness and performance goals. They both have PhDs in exercise science, are widely published, have had their own athletic careers, and are both performance coaches alongside their day jobs. Originally from different sides of the Atlantic, their paths first crossed in Copenhagen in 2010 as research scientists at the Centre for Inflammation and Metabolism at Rigshospitalet (Copenhagen University Hospital). After discussing lots of science, spending many a mile pounding the trails, and frequent micro brew pub drinking sessions, they became firm friends. Thomas even got a "buy one get one free" deal out of the friendship, marrying one of Matt's best friends from home after a chance encounter during a training weekend for the CCC in Schwartzwald. Although they are once again separated by the Atlantic, Matt and Thomas meet up about once a year and have weekly video chats about science, running, and beer. This "nerd alert" was created as an outlet for some of the

To read more about the authors, click the buttons:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

Copyright © Thomas Solomon and Matt Laye. All rights reserved.