Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — Training load using your brain.

→ Part 2 — TRIMP, HRSS, and rTSS.

→ Part 1 — Training load using your brain.

→ Part 2 — TRIMP, HRSS, and rTSS.

How to measure your training load? Part 1 of 2.

How to monitor your training load with help from your self-assessing brain.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

18th Apr 2020.

Your training must be continually evolved in line with your needs to facilitate maximal gains and subsequent achievement of your goals. However, to “evolve” you need to monitor the stress being placed on you — you need to monitor your training load.

Reading time ~20-mins (4000-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

In the context of exercise, physical fitness is a set of attributes that you have or achieve that allow you to perform physical activity with vigour while physical fatigue is the reduction in the maximal force-generating capacity of your muscles which would lead to an inability to complete a task that was once achievable within a recent time frame. We can all agree that progressively-increasing your exercise dose over time leads to an increase in fitness. The Italian farm boy, Milo of Crotona, who lifted a growing bullock every day to become a legend of the ancient Olympiad and the “world’s strongest man”, understood this concept quite well. We can also agree that on a day-to-day basis you might feel fatigued following a hard session or a hard week of training. Both fitness and fatigue are influenced by the dose and type of exercise, your physiological and psychological characteristics, your current training status, and the environmental conditions, and all of these factors act simultaneously.

“Training load” reflects the physical and psychological stress (or strain) imposed on you, and it is influenced by all of these factors.

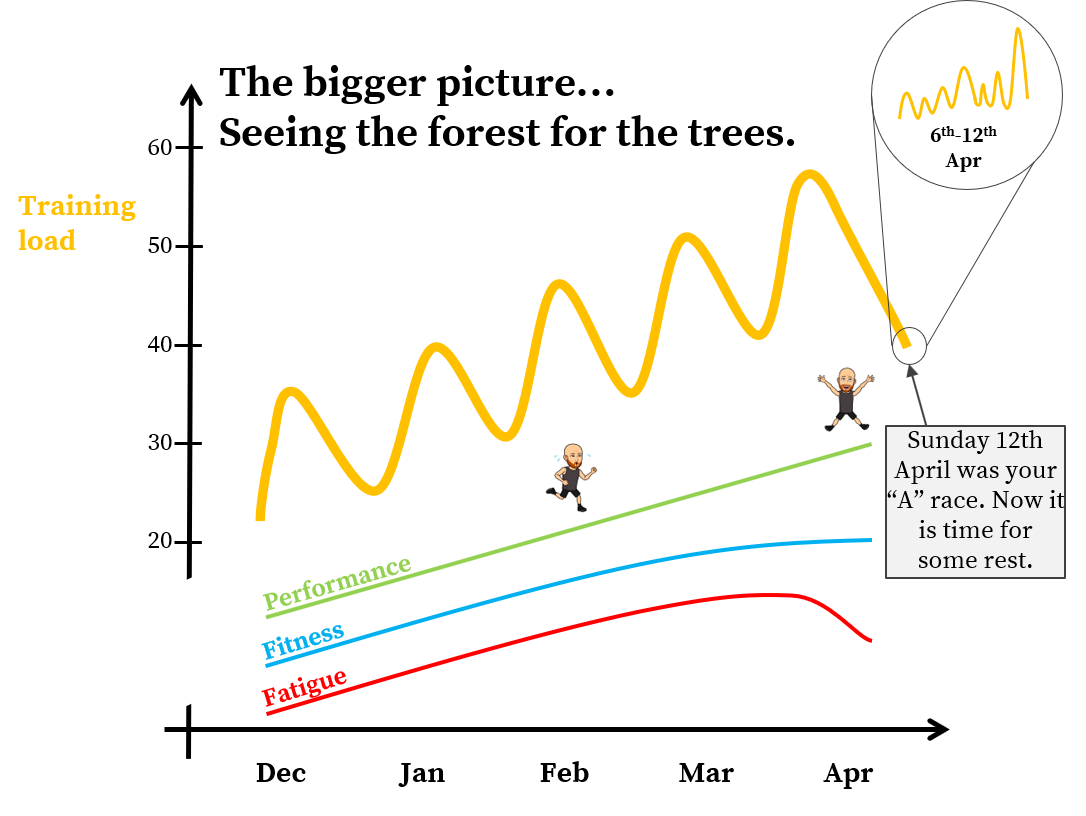

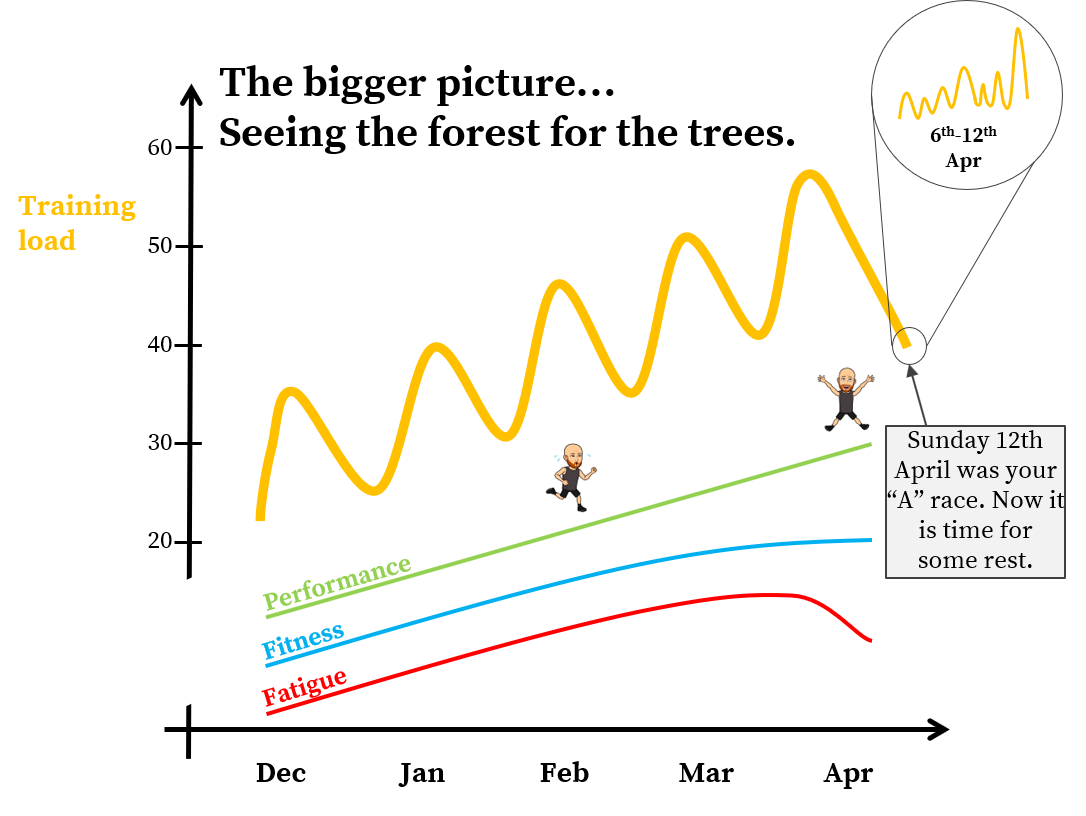

The main goal of your training is to “peak” your performance to be race-ready. To do so, you must tinker with your training load to elicit stress at various times of your training cycle. If we conceptualise your performance as a function of your accumulated fitness and current state of fatigue, adequate stress will be required to produce fatigue which, if adequate recovery is provided, prompts a stimulus for adaptation and a subsequent elevation in fitness and, eventually, performance.

Monitoring your training load is a scientific approach that helps you understand your responses to specific sessions and helps indicate whether or not you are adapting to your training programme. Analysing your past “load versus performance relationships” can also help you optimise your planned training load going forward. With such information, you can minimise the risk of non-functional overreaching (fatigue lasting weeks to months) and injury or illness, and you will be able to better hone your “race-readiness”. But, to monitor your training load you need to be able to measure it.

Measuring external load helps you understand your capabilities, and can include things like time, speed, and power output, etc. For example:

Exercise dose. The dose, i.e. the frequency, intensity, and time of each running session, and the volume load (sets × reps × weight per rep) for each strength session can easily be monitored.

Exercise dose. The dose, i.e. the frequency, intensity, and time of each running session, and the volume load (sets × reps × weight per rep) for each strength session can easily be monitored.

Exercise type. The type or modality of exercise can also easily be monitored. Running? Cycling? Lifting? Circuits? The number of intervals, their duration, etc.

Exercise type. The type or modality of exercise can also easily be monitored. Running? Cycling? Lifting? Circuits? The number of intervals, their duration, etc.

Velocity. Speed or pace, and acceleration can easily and accurately be measured in a sport-specific way with commercially-available GPS-on-the-wrist devices. Some platforms use (grade-adjusted) pace and time to generate a running total stress score (rTSS) metric to monitor training load.

Velocity. Speed or pace, and acceleration can easily and accurately be measured in a sport-specific way with commercially-available GPS-on-the-wrist devices. Some platforms use (grade-adjusted) pace and time to generate a running total stress score (rTSS) metric to monitor training load.

Power. Power output can also be measured in a sport-specific way. Some platforms use power and time to generate a running total stress score (rTSS) metric to monitor training load. But be aware that commercial accelerometry devices that estimate power during running can vary in their precision and repeatability.

Power. Power output can also be measured in a sport-specific way. Some platforms use power and time to generate a running total stress score (rTSS) metric to monitor training load. But be aware that commercial accelerometry devices that estimate power during running can vary in their precision and repeatability.

Neuromuscular function. Isokinetic dynamometry, is the gold standard for limb-specific measures of neuromuscular function but is expensive, cumbersome, and does not model sport-specific movements and is, therefore, typically uninformative for prescribing training. On the contrary, maximal height during vertical jumps, sprint performance, or 1-rep max (1RM) lifts can easily provide measures of neuromuscular function.

Neuromuscular function. Isokinetic dynamometry, is the gold standard for limb-specific measures of neuromuscular function but is expensive, cumbersome, and does not model sport-specific movements and is, therefore, typically uninformative for prescribing training. On the contrary, maximal height during vertical jumps, sprint performance, or 1-rep max (1RM) lifts can easily provide measures of neuromuscular function.

Measuring internal load helps you understand the subsequent adaptation to the exercise stimulus, and might include measuring perceived effort (RPE), heart rate, sleep, mood, etc. For example:

Rating of perceived exertion (RPE). A rating of perceived exertion or effort (RPE) is one of the most common means of assessing internal load. An athlete can self-monitor their RPE during an exercise bout (or reps-in-reserve during a lifting session) to ensure they are working at the correct intensity and a “session RPE” can be self-reported after the bout as a means of measuring internal load simply and quickly with no cost.

Rating of perceived exertion (RPE). A rating of perceived exertion or effort (RPE) is one of the most common means of assessing internal load. An athlete can self-monitor their RPE during an exercise bout (or reps-in-reserve during a lifting session) to ensure they are working at the correct intensity and a “session RPE” can be self-reported after the bout as a means of measuring internal load simply and quickly with no cost.

Heart rate. Monitoring heart rate (HR) is one of the most common means of assessing internal load in athletes. Resting heart rate is simple to measure and a lower resting HR correlates well with increased fitness but it only provides information about one aspect: how well the parasympathetic nervous system is working to calm down your physiological responses. Because HR is linearly related to the rate of oxygen consumption (VO2) during exercise, HR is also popularly used to monitor and prescribe exercise intensities. Some platforms track your average HR during a session in relation to your heart rate reserve, the difference between resting and maximum HR, to generate a heart rate stress score (HRSS) metric to monitor training load. Heart rate recovery from exercise can also be useful since it is a marker of autonomic function (the battle between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity), improves with training, remains unchanged during constant training, and deteriorates with inactivity. However, because of the natural day-to-day variation and the massive effect of things like hydration, environmental conditions, medications, and illness, daily HR variability can be as high as 6.5%, making heart rate variability a very difficult metric to interpret with confidence (Note: this is a topic I will discuss in detail very soon).

Heart rate. Monitoring heart rate (HR) is one of the most common means of assessing internal load in athletes. Resting heart rate is simple to measure and a lower resting HR correlates well with increased fitness but it only provides information about one aspect: how well the parasympathetic nervous system is working to calm down your physiological responses. Because HR is linearly related to the rate of oxygen consumption (VO2) during exercise, HR is also popularly used to monitor and prescribe exercise intensities. Some platforms track your average HR during a session in relation to your heart rate reserve, the difference between resting and maximum HR, to generate a heart rate stress score (HRSS) metric to monitor training load. Heart rate recovery from exercise can also be useful since it is a marker of autonomic function (the battle between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity), improves with training, remains unchanged during constant training, and deteriorates with inactivity. However, because of the natural day-to-day variation and the massive effect of things like hydration, environmental conditions, medications, and illness, daily HR variability can be as high as 6.5%, making heart rate variability a very difficult metric to interpret with confidence (Note: this is a topic I will discuss in detail very soon).

Sleep. Sleep duration and quality are associated with recovery from, adaptations to, and performance during exercise. Polysomnography is the gold-standard measurement for quantifying sleep quality. While consumer devices are becoming increasingly popular and, in some cases useful for detecting sleep duration, they are not yet an accurate surrogate for polysomnography-derived sleep quality. That said, nightly sleep duration and sleep quality can easily be recorded using a simple diary. More in-depth assessments can be made with a questionnaire like the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Sleep. Sleep duration and quality are associated with recovery from, adaptations to, and performance during exercise. Polysomnography is the gold-standard measurement for quantifying sleep quality. While consumer devices are becoming increasingly popular and, in some cases useful for detecting sleep duration, they are not yet an accurate surrogate for polysomnography-derived sleep quality. That said, nightly sleep duration and sleep quality can easily be recorded using a simple diary. More in-depth assessments can be made with a questionnaire like the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Nutrition. Energy availability, carbohydrate availability, and fat utilisation are also associated with recovery from, adaptations to, and performance during exercise. Nutritional analyses from daily diet records are difficult to perform with accuracy but a simple self-assessment of whether you feel you ate enough and whether you feel you ate well are useful for understanding your responses to exercise stimuli.

Nutrition. Energy availability, carbohydrate availability, and fat utilisation are also associated with recovery from, adaptations to, and performance during exercise. Nutritional analyses from daily diet records are difficult to perform with accuracy but a simple self-assessment of whether you feel you ate enough and whether you feel you ate well are useful for understanding your responses to exercise stimuli.

Menstruation. A high exercise dose combined with insufficient energy availability is associated with loss of reproductive function, which must be avoided in order to maintain an athlete’s reproductive health and bone status. A self-reported log to monitor the regularity of menses can, therefore, help to assess internal load and detect infrequent (oligomenorrhea), or absent (amenorrhoea), menstruation.

Menstruation. A high exercise dose combined with insufficient energy availability is associated with loss of reproductive function, which must be avoided in order to maintain an athlete’s reproductive health and bone status. A self-reported log to monitor the regularity of menses can, therefore, help to assess internal load and detect infrequent (oligomenorrhea), or absent (amenorrhoea), menstruation.

Illness or injury. What is wrong? How long has it been an issue? And, are you seeking professional medical support? A simple log of illness and injuries is a useful way to understand your responses to exercise.

Illness or injury. What is wrong? How long has it been an issue? And, are you seeking professional medical support? A simple log of illness and injuries is a useful way to understand your responses to exercise.

Psychology. Inappropriately increasing one’s training load can suppress mood and decrease performance. Self-reported levels of stress, anxiety, motivation, mood, and feelings of happiness can easily be assessed using questionnaires like the Profile of Mood States (POMS) or Daily Analysis of Life Demands for Athletes (DALDA). Self-reported measures of fatigue can also easily be monitored using questionnaires like the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for athletes (REST-Q-Sport) or Total Recovery Scale (TQR).

Psychology. Inappropriately increasing one’s training load can suppress mood and decrease performance. Self-reported levels of stress, anxiety, motivation, mood, and feelings of happiness can easily be assessed using questionnaires like the Profile of Mood States (POMS) or Daily Analysis of Life Demands for Athletes (DALDA). Self-reported measures of fatigue can also easily be monitored using questionnaires like the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for athletes (REST-Q-Sport) or Total Recovery Scale (TQR).

Blood markers. Common biochemical, hormonal, and immunological blood measurements that are related to fatigue or illness, include creatine kinase, cortisol, testosterone, and IgA. However, these require complex and expensive methodology and expert interpretation and, despite large research efforts, none of them accurately assess recovery or predict performance. On the other hand, blood lactate which can easily be measured with precision and accuracy under laboratory conditions and with some consumer finger-prick devices, gives useful info regarding the intensity of a session. But, training in and experience of appropriate blood sampling and measurement are required and it is not always practical to measure lactate during every session in the field.

Blood markers. Common biochemical, hormonal, and immunological blood measurements that are related to fatigue or illness, include creatine kinase, cortisol, testosterone, and IgA. However, these require complex and expensive methodology and expert interpretation and, despite large research efforts, none of them accurately assess recovery or predict performance. On the other hand, blood lactate which can easily be measured with precision and accuracy under laboratory conditions and with some consumer finger-prick devices, gives useful info regarding the intensity of a session. But, training in and experience of appropriate blood sampling and measurement are required and it is not always practical to measure lactate during every session in the field.

As you can see, the stress imposed on you by your training can be monitored in many ways. But it might also seem obvious that picking just one of the variables will only provide you with one glimpse into your true training load. It is important to think of each variable as a single piece of a complex jigsaw puzzle - the more pieces you have, the clearer the final picture becomes.

In the age of GPS-on-the-wrist, it is very easy to collect speed, distance, and time data, logging it all online to examine it in line with your exercise dose (frequency, intensity, and time) and exercise type. In 2005, scientists in NZ and Australia collected data from ~55 practitioners (coaches and sports scientists) who manage elite or professional athletes in high-performance centres or teams across a large variety of sports, including running. The practitioners reported that the aims of their monitoring systems were “to prevent overtraining, reduce injuries, monitor training effectiveness, and ensure the maintenance of performance throughout competitive periods”. Interestingly, they reported high usage of self-report questionnaires with less reliance on expensive or complex tools. The majority of practitioners also reported that they relied on visually-identifying trends in individual data, usually detected by a decline in a metric over successive days or sessions. Some of the tools like “feelings of fatigue” were used daily while others, like sport-specific fitness tests, were implemented only monthly.

By listening to interviews with many of the greats of the running and obstacle-racing world, including Kilian Jornet, Jon Albon, Lyndsey Webster, Eliud Kipchoge, Jim Walmsley, Camille Heron, and Chrissie Wellington, many of whom self-coach and self-assess their training load and recovery needs, you will hear one very clear and resounding message… “Listen to your body”. Even if your performance level is a world away from theirs, take their resounding memo to heart.

What is the message here? Many high-performance programmes regularly assess training loads primarily using self-reported measures combined with external load metrics. It is very important to collect data, regularly but sensibly so as not to get swamped. It is also important not to forget the highly-informative tool that is the athlete’s subjective self-assessing brain. “Listening to your body” is a metric that can be quantified and monitored, as I will explain in a moment. Combining that with GPS-on-the-wrist-derived speed, elevation gain, distance, and time (or distance and time estimates for my old school folks) has always proven to be very useful.

The rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was originally developed by Gunnar Borg in the 1970s. But, in the 90s, Carl Foster developed the RPE as a gauge of exercise intensity to estimate a training load score. It basically boils down to asking yourself after your session, “how did that feel?”, ranking the feeling of exertion out of 10 to generate a session-RPE and multiplying that by the length of your session. No fancy gadgets, just some mental arithmetic.

Session-RPE is an excellent marker of heart rate and blood lactate responses to exercise. A systematic review recently confirmed the validity and reliability of session-RPE as a measure of training load in men and women of all ages and levels of competition in a large array of sports. The session-RPE training load score has, in many studies, been shown to predict performance as well as heart rate and speed-derived measures in sports that include running and running-related tasks. Furthermore, in runners, RPE shows the lowest day-to-day biological variation when compared to other training load-associated variables, including heart rate and blood lactate. However, the accuracy of session-RPE may deviate when large amounts of training time are spent at very high or very low intensities. Also, a session-RPE reflects the overall intensity of the whole session and may not reflect the true stress imposed by an intermittent session. Hence the need for “exercise type” info such as the number, duration and RPE of intervals.

As a coach, recording basic variables of each session and combining that with the athlete’s subjective assessment of how the session felt and how much effort they unleashed, provides an ever-growing database from which signals can be detected from the noise and out-of-the-ordinary patterns can be recognised and acted on accordingly. I have used this approach for several years, to great effect. Remember that, if a tree in the forest falls with no one around to hear it, it does still make a sound. Based on that principle, here is a suggested approach:

Immediately after every session, ask yourself:

Immediately after every session, ask yourself:

"What was my perceived level of exertion today?" (session-RPE; aka intensity)

Rate your “RPE” during the session out of 10, where 2 = walking and 10 = maximal effort. To supplement the session-RPE intensity rating, you may also record (grade-adjusted) pace, heart rate, power, or weight lifting, in order to help track real performance outcomes.

And,

Ask yourself:

Ask yourself:

"How did I feel?"

Rate your feeling during the session out of 5, where 5 = "I felt like the hulk", 4 = “I felt good”, 3 = “I felt average and/or a bit flat or off”, 2 = “I felt rubbish and could not maintain the quality throughout”, 1 = “I felt so terrible, tired, or ill, that I did not train or had to abort mission”.

Then,

Record:

Record:

Session duration (time, or sets ✕ reps for weights sessions)

Session type (terrain, elevation gain, intervals/steady-state, interval number, interval duration, and interval-RPE)

And,

Calculate your session’s training load:

Calculate your session’s training load:

Multiply the session-RPE by the session-duration (in minutes) or, for a weights session, multiply the session-RPE by the number of sets and the number of reps.

Online platforms like Strava (the paid subscription version only), Training Peaks, and Final Surge feed your exercise intensity, time, and speed or heart rate metrics (HRSS, or rTSS) into their “training impulse” algorithms to derive estimates of your “Fitness” and “Fatigue”, to estimate your “Performance” (or “Form”). The web-based extension Elevate also calculates these metrics and, for the time being (this is due to change soon), “piggy-backs” your Strava account for free. Strava also allows you to rate your “session-RPE” while Training Peaks and Final Surge make additional use of your subjective self-assessing brain and allow you to rate your “session feeling” after each workout. However, none* of these platforms analyses or incorporates your feelings into their fitness-fatigue model “prediction” of your performance (*Strava now do use your RPE but how they use it is proprietary) nor can you view a trend of your self-reported feelings over time. Further considerations are that a fitness-fatigue model is only as accurate as the input, which, in this case, is your HR or pace at lactate threshold, which changes with training and detraining and therefore must be adjusted regularly for the model to fit you more accurately. But the most important limitation of these fitness-fatigue models that all online training platforms use (Strava, Training Peaks, Final Surge, etc etc) is that load and stress are two different things — a “load” such as a running pace can be the same on two sessions but, because of greater prevailing fatigue or poorer nutritional/hydration status, or hotter environmental conditions, the “stress” can be very different. For example, you might go for a 30-minute tempo effort run at 3:45/km (6:00/mile) on one day and record a stable heart rate at 160 bpm over the last 20-mins. But, on a separate day, you attempt the same run on the same course at 3:45/km but it feels harder (greater RPE) from the outset, your heart rate drifts higher and higher and reaches near max, and maintaining 3:45/km becomes nigh on impossible as fatigue sets it. In this scenario, the external load — measured as TSS by online platforms — is the same for the two sessions but the internal load — measured as HRSS by online platforms — is much higher for the second of the two sessions. Obviously, the second of the two workouts “felt harder” and was therefore a bigger “stress” as partly indicated by the greater cardiovascular strain (greater heart rate), which would therefore be captured by a heart-rate-derived metric like HRSS. Meanwhile, the TSS metric would miss the true stress caused by the workout. The same is true for sessions that place you under a heavy load that is not recognised by an overt heart rate response. For example, metrics like TRIMP, HRSS, or TSS that use heart rate or speed above lactate threshold won't detect 6 × 150m sprint off 5-min rest as a significant stress because it is only ~2-mins of fast work. Yet, the biomechanical load and subsequent stress caused by such a session is large but TRIMP, HRSS, or TSS will not see it that way...

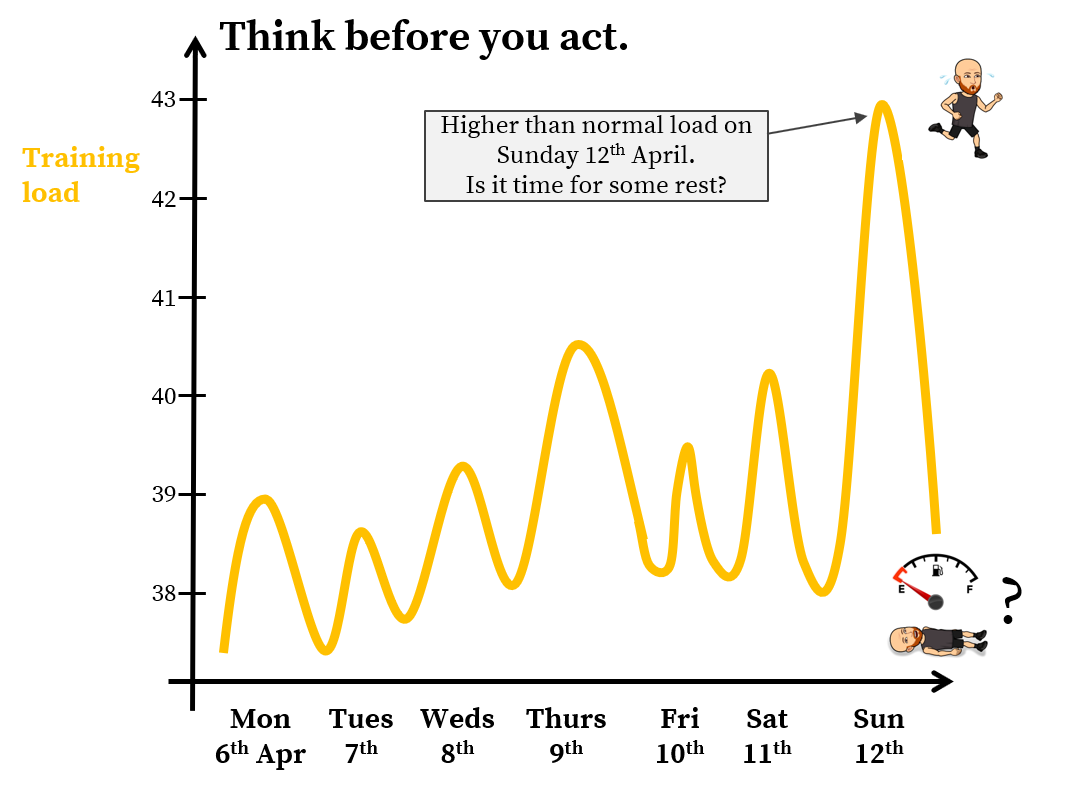

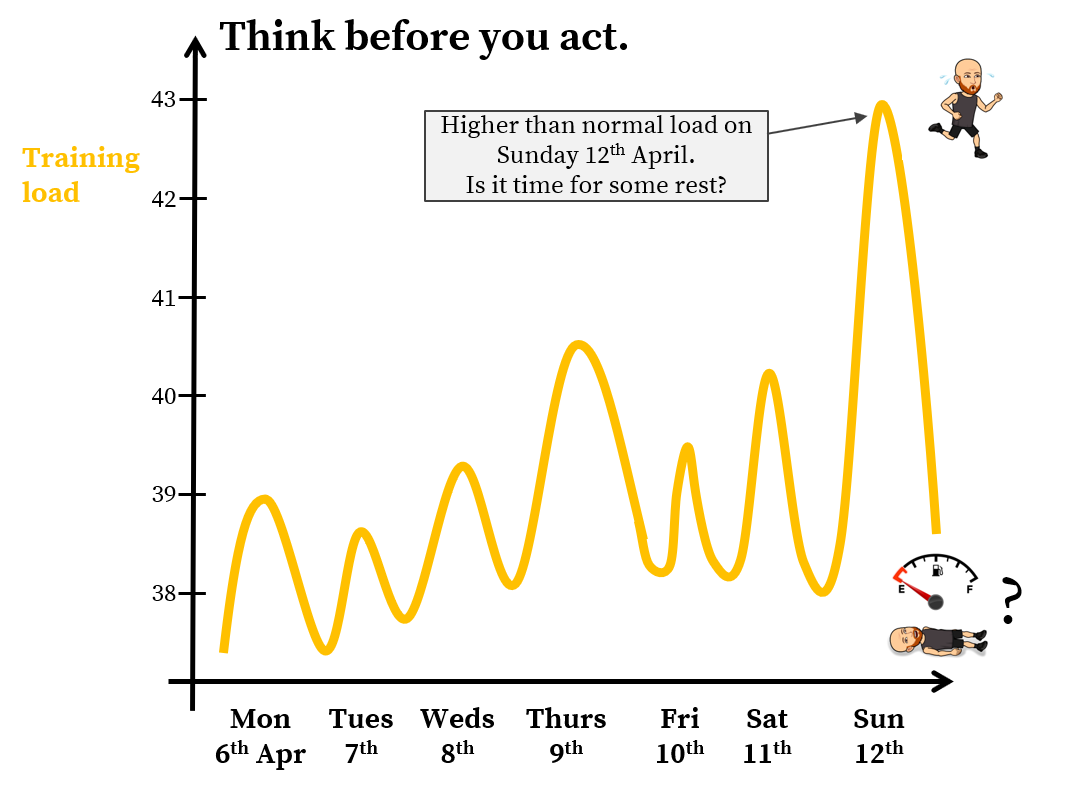

The most important thing to remember is that data without knowledge is useless — as Nate Silver once said, “The numbers have no way of speaking for themselves. We speak for them. We imbue them with meaning”. A single data point without a frame of reference is not useful. Therefore, regular monitoring is very important. Building up a profile of data will help you spot patterns. But, separating a signal from technical noise is tricky, especially when using things like heart rate - so many factors can influence your heart rate, and these go beyond how hard your session was.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

If you are amidst a specifically well-planned week of overreaching (i.e. functional overreaching), where the goal is to accumulate more-than-usual fatigue followed by more-than-usual rest, then the day-to-day session-RPE and your associated feelings will be very predictable and can be temporarily ignored. But, functional overreaching periods should be brief and infrequent and not a weekly feature in your planning. During periods of “normal” training, you must pay attention to your RPE and your feelings as they provide huge amounts of information that automated metrics do not and cannot reveal.

Suggested rule of thumb #1.

Suggested rule of thumb #1.

If you trained Hard today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after. I.e., if your overall session-RPE today was 6 out of 10 or higher then you pushed your body into the “heavy” biological intensity domain and will need to reduce the intensity for one or two days so that you plan only to complete low-intensity activities (RPE less than 5 out of 10) in the “easy” domain.

Suggested rule of thumb #2.

Suggested rule of thumb #2.

If you accumulated Hard-time today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after. I.e., if your session included blocks of time at or above RPE 6/10 (this includes anything at or faster than your marathon pace/effort) then reduce the intensity into the “easy” domain (RPE < 5/10) for one or two days.

Suggested rule of thumb #3.

Suggested rule of thumb #3.

If you felt like total shit today, you probably need some rest. Generally, however, remember that when rating how you felt during a session, not every session has to be a “5” and the occasional “1” is totally fine. But, if things don't feel right, there is no shame in “aborting mission” ; it is ALWAYS best to stop, recover, and delay until you feel ready to produce the goods.

Suggested rule of thumb #4.

Suggested rule of thumb #4.

Do not ignore your feelings - they are your “thermostat”. If you consistently feel like a 3 or lower, don’t just shrug your shoulders and continue as if all is OK. This indicates that you are not recovering sufficiently from prior sessions - something needs to be changed. Without change, you will see the numbers falling, and eventually, you will be a zero - under-recovered and on the path to the dark side…

The world bombards us with devices that produce metrics. All automated metrics on all the above-described platforms make the assumption that looking at one or two pieces of the jigsaw puzzle (time, HR, pace, or power) can predict performance. The fitness (chronic load) vs. fatigue (acute load) models also make the assumption that the rate of decay of load is the same among all people. For example, in the model used by TrainingPeaks, it is assumed that fitness is an accumulation of your last 42-days of load and that fatigue is an accumulation of the last 7-days — sensible but arbitrary values that have not been validated and, since you are the only you, are not bespoke to your fitness/fatigue decay curves. Remember what we learned about assumptions from Tom in Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels? “It's the mother of all f-ups, stupid”. Such assumptions limit the utility of such metrics in sports where physical, technical, and tactical abilities represent true performance. This applies to running, particularly trail or mountain running, and especially obstacle course racing (OCR). The different aspects of fitness, like cardiorespiratory, strength, and skill, may develop and decay at different rates. Furthermore, other important variables, like psychology, environment, and pacing strategy, have a massive impact on competitive performance. Yes, some metrics like HRSS and rTSS sound fancy and help examine your responses to certain sessions, which can be useful for understanding the basic concepts of your fitness-fatigue relationships to help tweak or plan your future training loads. But in isolation, they are just one part of the picture…

I hope to have helped you learn that the stress placed on you as a result of your training is related to more than just time, speed, or heart rate. By now, you will probably have noticed that I like to encourage everyone to train smart. One easy way to help yourself do that is to “check-in” with yourself every day. How do you feel? Are you sleeping well? Are you eating well? Are you resting enough? These are questions only you can answer.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. Until next time, keeptraining smart assessing your feelings.

The main goal of your training is to “peak” your performance to be race-ready. To do so, you must tinker with your training load to elicit stress at various times of your training cycle. If we conceptualise your performance as a function of your accumulated fitness and current state of fatigue, adequate stress will be required to produce fatigue which, if adequate recovery is provided, prompts a stimulus for adaptation and a subsequent elevation in fitness and, eventually, performance.

Monitoring your training load is a scientific approach that helps you understand your responses to specific sessions and helps indicate whether or not you are adapting to your training programme. Analysing your past “load versus performance relationships” can also help you optimise your planned training load going forward. With such information, you can minimise the risk of non-functional overreaching (fatigue lasting weeks to months) and injury or illness, and you will be able to better hone your “race-readiness”. But, to monitor your training load you need to be able to measure it.

The complexity of measuring training load.

Monitoring your training load requires a tool that quantifies both the work done (i.e. your “external” load) and the physiological and psychological stress imposed by the work (i.e. your “internal” load). The relationship between external and internal loads helps to understand changes in accumulated fitness and current fatigue.Measuring external load helps you understand your capabilities, and can include things like time, speed, and power output, etc. For example:

So, what can you do?

Data is nerdy and exciting, and patterns can look cool. Data collection can also enhance the coach-athlete relationship, make athletes be accountable and take responsibility for their training while also fuelling their motivation and helping empower them to lead their own journey. But, data collection also costs time, resources, and, in some cases, money, which are luxuries not everyone can afford. There is also no guarantee that simply having data leads to performance gains because without knowledge and experience, data can be uninformative or misleading and, worst-case, will lead to misinterpretations and poor decision-making.In the age of GPS-on-the-wrist, it is very easy to collect speed, distance, and time data, logging it all online to examine it in line with your exercise dose (frequency, intensity, and time) and exercise type. In 2005, scientists in NZ and Australia collected data from ~55 practitioners (coaches and sports scientists) who manage elite or professional athletes in high-performance centres or teams across a large variety of sports, including running. The practitioners reported that the aims of their monitoring systems were “to prevent overtraining, reduce injuries, monitor training effectiveness, and ensure the maintenance of performance throughout competitive periods”. Interestingly, they reported high usage of self-report questionnaires with less reliance on expensive or complex tools. The majority of practitioners also reported that they relied on visually-identifying trends in individual data, usually detected by a decline in a metric over successive days or sessions. Some of the tools like “feelings of fatigue” were used daily while others, like sport-specific fitness tests, were implemented only monthly.

By listening to interviews with many of the greats of the running and obstacle-racing world, including Kilian Jornet, Jon Albon, Lyndsey Webster, Eliud Kipchoge, Jim Walmsley, Camille Heron, and Chrissie Wellington, many of whom self-coach and self-assess their training load and recovery needs, you will hear one very clear and resounding message… “Listen to your body”. Even if your performance level is a world away from theirs, take their resounding memo to heart.

What is the message here? Many high-performance programmes regularly assess training loads primarily using self-reported measures combined with external load metrics. It is very important to collect data, regularly but sensibly so as not to get swamped. It is also important not to forget the highly-informative tool that is the athlete’s subjective self-assessing brain. “Listening to your body” is a metric that can be quantified and monitored, as I will explain in a moment. Combining that with GPS-on-the-wrist-derived speed, elevation gain, distance, and time (or distance and time estimates for my old school folks) has always proven to be very useful.

The case for using your brain for helping to assess your training load.

While devices can provide some helpful insight, you should never rely on device-derived metrics to tell you how you feel. Your own brain is able to process all inputs rapidly and without error to produce an informative metric of how you feel. Intuitively, therefore, it is you who is the Jedi master of your own feelings and it is you who should be telling your device how you feel, not the other way around. But, how do you rate how you are feeling?The rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was originally developed by Gunnar Borg in the 1970s. But, in the 90s, Carl Foster developed the RPE as a gauge of exercise intensity to estimate a training load score. It basically boils down to asking yourself after your session, “how did that feel?”, ranking the feeling of exertion out of 10 to generate a session-RPE and multiplying that by the length of your session. No fancy gadgets, just some mental arithmetic.

Assess your daily training load with simplicity.

In my experience as a practitioner, after several months of data collection, athletes become intuitive - they learn to understand that a self-assessed “how do I feel” rated at 2 out of 5 on the morning after a very hard session which they rated as 9/10 on an RPE scale, means that you need to go Easy for at least 2-days, perhaps longer.As a coach, recording basic variables of each session and combining that with the athlete’s subjective assessment of how the session felt and how much effort they unleashed, provides an ever-growing database from which signals can be detected from the noise and out-of-the-ordinary patterns can be recognised and acted on accordingly. I have used this approach for several years, to great effect. Remember that, if a tree in the forest falls with no one around to hear it, it does still make a sound. Based on that principle, here is a suggested approach:

"What was my perceived level of exertion today?" (session-RPE; aka intensity)

Rate your “RPE” during the session out of 10, where 2 = walking and 10 = maximal effort. To supplement the session-RPE intensity rating, you may also record (grade-adjusted) pace, heart rate, power, or weight lifting, in order to help track real performance outcomes.

And,

"How did I feel?"

Rate your feeling during the session out of 5, where 5 = "I felt like the hulk", 4 = “I felt good”, 3 = “I felt average and/or a bit flat or off”, 2 = “I felt rubbish and could not maintain the quality throughout”, 1 = “I felt so terrible, tired, or ill, that I did not train or had to abort mission”.

Then,

Session duration (time, or sets ✕ reps for weights sessions)

Session type (terrain, elevation gain, intervals/steady-state, interval number, interval duration, and interval-RPE)

And,

Multiply the session-RPE by the session-duration (in minutes) or, for a weights session, multiply the session-RPE by the number of sets and the number of reps.

But, can’t you just rely on automated metrics?

Over the last 10-years, the wearable industry exploded. Wearable technology, which is a 95-billion dollar industry, took over the no. 1 spot in the ACSM’s “Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2020”. Following the boom in access to wearables, automated metrics have followed. Polar has their “Running Index” score, which estimates your current VO2max based on an algorithm assessing the accumulative 12-minute relationship between HR and speed during a session, while Garmin also automatically guesstimates your VO2max after each session and tells you how many hours you need to rest for until your next session. Garmin also has its “Training Effect” score, which indicates the extent to which your session impacted your fitness. Unfortunately, algorithms behind such metrics are proprietary “black box” models (mostly provided by the Finnish company, Firstbeat Technologies) and their accuracy and precision have not been validated in peer-reviewed scientific studies.Online platforms like Strava (the paid subscription version only), Training Peaks, and Final Surge feed your exercise intensity, time, and speed or heart rate metrics (HRSS, or rTSS) into their “training impulse” algorithms to derive estimates of your “Fitness” and “Fatigue”, to estimate your “Performance” (or “Form”). The web-based extension Elevate also calculates these metrics and, for the time being (this is due to change soon), “piggy-backs” your Strava account for free. Strava also allows you to rate your “session-RPE” while Training Peaks and Final Surge make additional use of your subjective self-assessing brain and allow you to rate your “session feeling” after each workout. However, none* of these platforms analyses or incorporates your feelings into their fitness-fatigue model “prediction” of your performance (*Strava now do use your RPE but how they use it is proprietary) nor can you view a trend of your self-reported feelings over time. Further considerations are that a fitness-fatigue model is only as accurate as the input, which, in this case, is your HR or pace at lactate threshold, which changes with training and detraining and therefore must be adjusted regularly for the model to fit you more accurately. But the most important limitation of these fitness-fatigue models that all online training platforms use (Strava, Training Peaks, Final Surge, etc etc) is that load and stress are two different things — a “load” such as a running pace can be the same on two sessions but, because of greater prevailing fatigue or poorer nutritional/hydration status, or hotter environmental conditions, the “stress” can be very different. For example, you might go for a 30-minute tempo effort run at 3:45/km (6:00/mile) on one day and record a stable heart rate at 160 bpm over the last 20-mins. But, on a separate day, you attempt the same run on the same course at 3:45/km but it feels harder (greater RPE) from the outset, your heart rate drifts higher and higher and reaches near max, and maintaining 3:45/km becomes nigh on impossible as fatigue sets it. In this scenario, the external load — measured as TSS by online platforms — is the same for the two sessions but the internal load — measured as HRSS by online platforms — is much higher for the second of the two sessions. Obviously, the second of the two workouts “felt harder” and was therefore a bigger “stress” as partly indicated by the greater cardiovascular strain (greater heart rate), which would therefore be captured by a heart-rate-derived metric like HRSS. Meanwhile, the TSS metric would miss the true stress caused by the workout. The same is true for sessions that place you under a heavy load that is not recognised by an overt heart rate response. For example, metrics like TRIMP, HRSS, or TSS that use heart rate or speed above lactate threshold won't detect 6 × 150m sprint off 5-min rest as a significant stress because it is only ~2-mins of fast work. Yet, the biomechanical load and subsequent stress caused by such a session is large but TRIMP, HRSS, or TSS will not see it that way...

Separating the signal from the noise

If you're going to collect training data, you need to be able to analyse it, make accurate inferences, and act accordingly and appropriately. The whole purpose of monitoring training load is to keep you on track, progressing gradually in a safe, healthy, and clean manner. The approach must be able to identify what is real and separate it from what is simply a natural variation in your own physiology or technical variation of the method you are using. I.e., the approach must separate the true signal from the noise.The most important thing to remember is that data without knowledge is useless — as Nate Silver once said, “The numbers have no way of speaking for themselves. We speak for them. We imbue them with meaning”. A single data point without a frame of reference is not useful. Therefore, regular monitoring is very important. Building up a profile of data will help you spot patterns. But, separating a signal from technical noise is tricky, especially when using things like heart rate - so many factors can influence your heart rate, and these go beyond how hard your session was.

×

![]()

A reduction in your internal load response (RPE or heart rate, for example) to a standardised external load might indicate that your fitness is increasing and that you are handling the overall training. Conversely, an increase in that same RPE or heart rate response to an identical dose and type of external load might indicate that you are losing fitness or are fatigued. However, in isolation, a single day’s data point is not informative. Minor day-to-day variability can be ignored. Instead of trying to interpret every single blip, use a method to collect frequent sampling points and learn to recognize your patterns. Real “changes” in variables must be larger than their typical error of measurement, i.e. larger than the natural variation of their method. Learning to recognise your own day-to-day variability will also provide you with knowledge of the smallest worthwhile change that should cause you to act. This will bring you confidence when making decisions based on changes in your training load data.

×

![]()

Using data to inform decisions.

Fitness vs. fatigue or acute (very recent) vs. chronic (long-term) load models are useful for understanding your responses to sessions and while helping you to conceptualise the very basic concepts of training adaptations. Doing so can help you plan future training loads in order to hit a peak. But simply “planning” a recipe to “peak” your performance for an event will not achieve maximal results if the pie is simply left in the oven. You must look for the cues that indicate the opportune moments for optimisation. The simple questions, “how hard was it?” and “how did it feel?” provide just the info you need and, as you learn to master the relationship between the answers to those questions, Yoda will soon come knocking to present you with your lightsaber.If you are amidst a specifically well-planned week of overreaching (i.e. functional overreaching), where the goal is to accumulate more-than-usual fatigue followed by more-than-usual rest, then the day-to-day session-RPE and your associated feelings will be very predictable and can be temporarily ignored. But, functional overreaching periods should be brief and infrequent and not a weekly feature in your planning. During periods of “normal” training, you must pay attention to your RPE and your feelings as they provide huge amounts of information that automated metrics do not and cannot reveal.

If you trained Hard today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after. I.e., if your overall session-RPE today was 6 out of 10 or higher then you pushed your body into the “heavy” biological intensity domain and will need to reduce the intensity for one or two days so that you plan only to complete low-intensity activities (RPE less than 5 out of 10) in the “easy” domain.

If you accumulated Hard-time today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after. I.e., if your session included blocks of time at or above RPE 6/10 (this includes anything at or faster than your marathon pace/effort) then reduce the intensity into the “easy” domain (RPE < 5/10) for one or two days.

If you felt like total shit today, you probably need some rest. Generally, however, remember that when rating how you felt during a session, not every session has to be a “5” and the occasional “1” is totally fine. But, if things don't feel right, there is no shame in “aborting mission” ; it is ALWAYS best to stop, recover, and delay until you feel ready to produce the goods.

Do not ignore your feelings - they are your “thermostat”. If you consistently feel like a 3 or lower, don’t just shrug your shoulders and continue as if all is OK. This indicates that you are not recovering sufficiently from prior sessions - something needs to be changed. Without change, you will see the numbers falling, and eventually, you will be a zero - under-recovered and on the path to the dark side…

Avoid becoming a slave to fancy-sounding metrics.

Your system for monitoring your training load should be simple to implement, easy to use, and cost-effective. It should collect data on internal load (e.g. exercise dose [frequency, intensity, time] for each type of training) and external load (e.g. RPE, feelings, mood, sleep, nutrition, etc). Your system should also be easy to analyse and interpret, individualised to you (or your athletes) and therefore taking into account the error of measurement and within-person variability. And, importantly, it should identify meaningful changes (i.e. isolate the signal from the noise) and report meaningful changes clearly so they can be acted on accordingly.The world bombards us with devices that produce metrics. All automated metrics on all the above-described platforms make the assumption that looking at one or two pieces of the jigsaw puzzle (time, HR, pace, or power) can predict performance. The fitness (chronic load) vs. fatigue (acute load) models also make the assumption that the rate of decay of load is the same among all people. For example, in the model used by TrainingPeaks, it is assumed that fitness is an accumulation of your last 42-days of load and that fatigue is an accumulation of the last 7-days — sensible but arbitrary values that have not been validated and, since you are the only you, are not bespoke to your fitness/fatigue decay curves. Remember what we learned about assumptions from Tom in Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels? “It's the mother of all f-ups, stupid”. Such assumptions limit the utility of such metrics in sports where physical, technical, and tactical abilities represent true performance. This applies to running, particularly trail or mountain running, and especially obstacle course racing (OCR). The different aspects of fitness, like cardiorespiratory, strength, and skill, may develop and decay at different rates. Furthermore, other important variables, like psychology, environment, and pacing strategy, have a massive impact on competitive performance. Yes, some metrics like HRSS and rTSS sound fancy and help examine your responses to certain sessions, which can be useful for understanding the basic concepts of your fitness-fatigue relationships to help tweak or plan your future training loads. But in isolation, they are just one part of the picture…

I hope to have helped you learn that the stress placed on you as a result of your training is related to more than just time, speed, or heart rate. By now, you will probably have noticed that I like to encourage everyone to train smart. One easy way to help yourself do that is to “check-in” with yourself every day. How do you feel? Are you sleeping well? Are you eating well? Are you resting enough? These are questions only you can answer.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. Until next time, keep

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.