Opinion:

We are not getting faster; there are just more of us and we are more accessible.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

28th Oct 2020.

Reading time ~7-mins (1400-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Since the late 1800s, our knowledge of training methods, nutrition, exercise-nutrient interactions, supplements, etc, has boomed. In this electronic web-connected age, access to this knowledge is ubiquitous. Unfortunately, knowledge of and access to performance-enhancing drugs have also increased while the rate of development to increase testing sensitivity has not kept up.

Technology has also improved — track spikes first appeared in the 1850s, then we had cushioned “waffle sole” shoes, now we have carbon-fibre plated shoes with crazy stack heights and super-light foams. Each thing we add to the mix “might” add something to our performance — the collection of 1-percents is what Dave Brailsford would call “marginal gains”. But there is a limit to how many marginal gains can be made.

Once upon a time, we stood up — Homo erectus — our likely (and also now extinct) ancestor. We evolved to move on hindlimbs. We evolved to run, to “outrun” prey so that we could eat. Running is one of the many attributes that have helped us survive the test of time. But today, our running performance no longer needs to “evolve” because most of us no longer need to outrun lions — to avoid being eaten — or outrun antelope — to avoid being hungry — and those of us who do need these skills are already well-adapted for doing so, otherwise they would not be here.

So, the first important question to consider is...

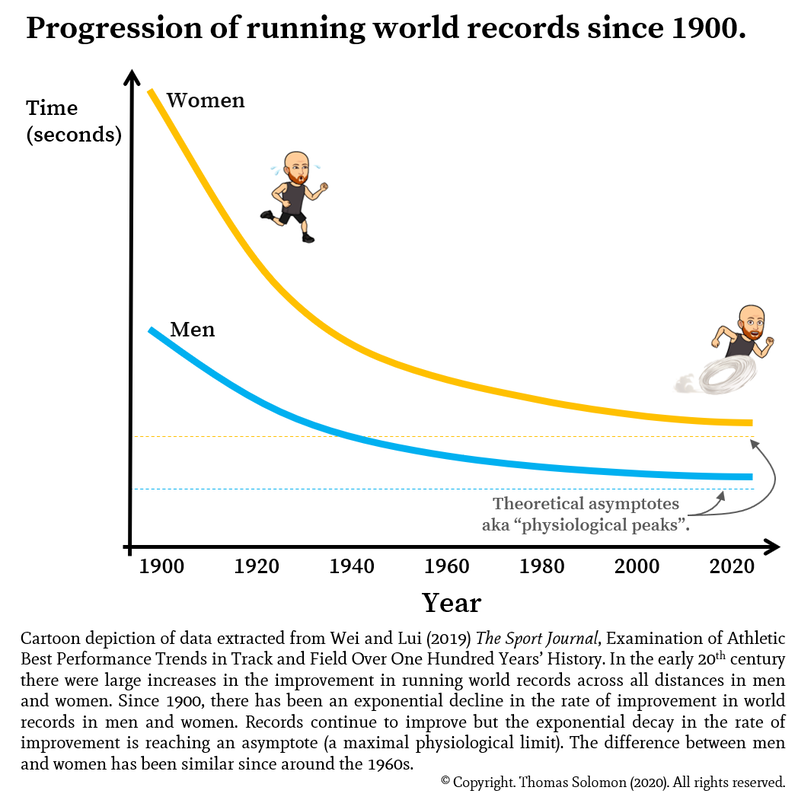

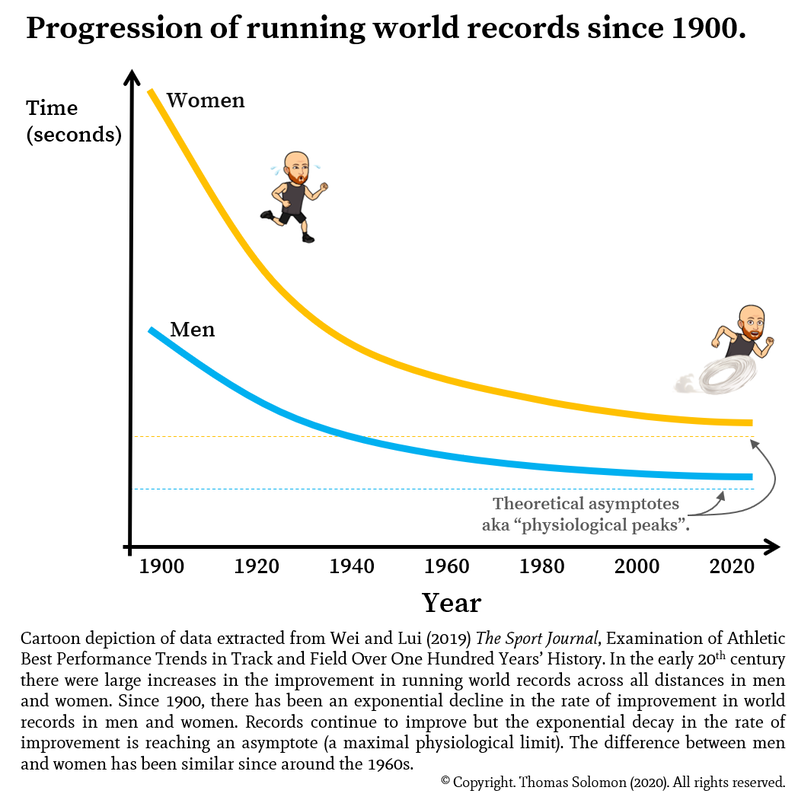

But isolated observations simply tickle our excitement and do not tell us much regarding progress. Examining the trends in world records across the ages reveals some clues. Recently, scientists at Western Michigan University examined the best running performances in distances from 100m to the marathon between 1900 and 2018. They found that performances in all events have made massive improvements but are reaching an asymptote — a physiological peak — in both men and women. Other research has identified the same trends in swimming, race walking, and powerlifting, and shows that world records have reached about 99% of their predicted asymptotes.

Similar work from Giuseppe Lippi at the University of Verona and his colleagues from various universities around the world, found that the time-dependent progression in world record running times over the same timeframe has slowed to a near plateau, concluding that the dramatic advances in times since 1900 “might be explained by a variety of factors, including social and environmental changes, natural selection, advances in training and sport physiology, ergogenic aids and, possibly, doping”.

This conclusion from Lippi and colleagues is a pretty typical comment from observers of trends in improvements in human performance. We certainly cannot deny that there have been advancements in the knowledge of and access to training, supplements, and doping. Plus, there have indeed been sociological advances in sport (for example, more women are choosing to participate and are now allowed to compete in all events), as well as technical progress (for example, Dick Fosbury’s flop or the Shot putters spin) and technological progress (spikes, cushioning, and the most important technological advance ever made in men’s running — the side-split flappy short-shorts). More recently, we also have the moral dilemma of carbon-fibre plated shoes, which sprinkle the most recent records with “technological artefact”, just like the now-banned “LZR” sharkskin suit did in swimming.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

But, I pose an additional perspective to ponder…

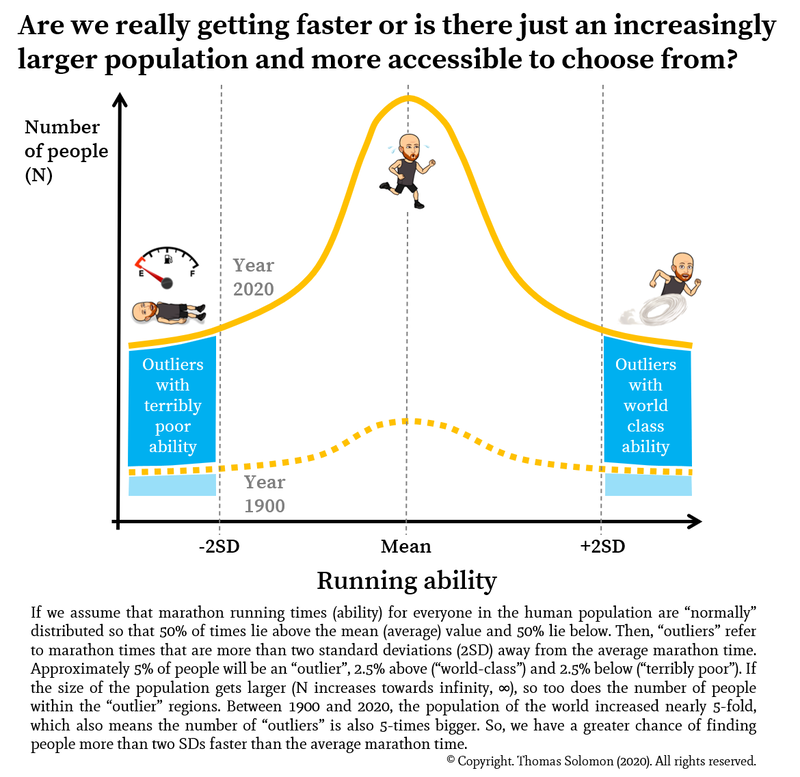

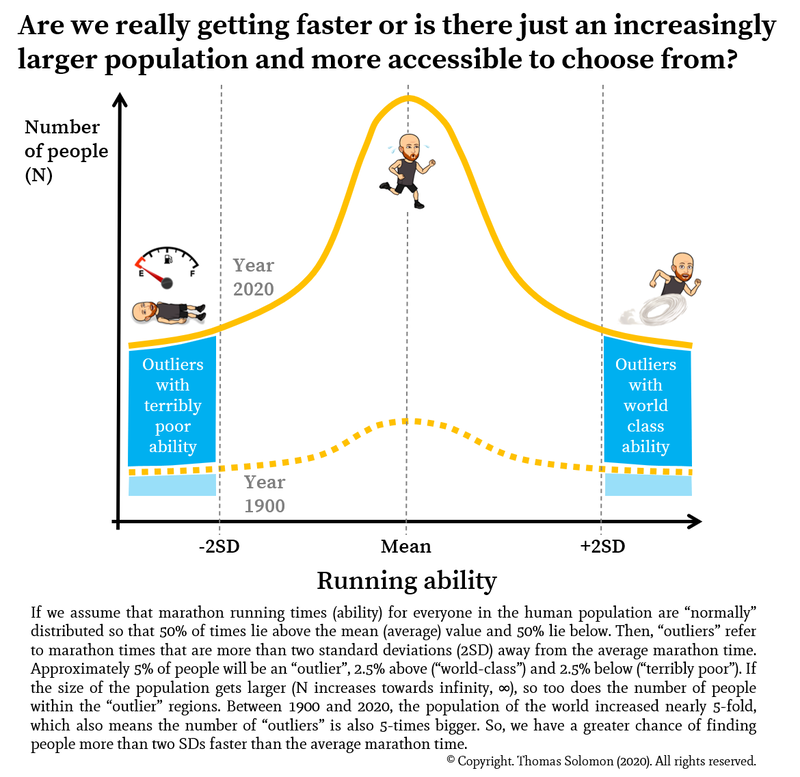

For the sake of keeping my argument simple, let’s look at a single event: the marathon… If we assume that marathon running times for everyone in the human population are “normally” distributed — meaning that 50% of times lie above the mean (average) value and 50% lie below the average — then, “outliers” would refer to marathon times that are more than two standard deviations away from the average marathon time. Without delving into the maths, this would mean that approximately 5% of times will be an “outlier” — 2.5% above (“world-class”) and 2.5% below (“terribly slow”). If the size of the population gets larger, so too does the number of people within the “outlier” regions of the normal distribution of times.

Between 1900 and 2020, the population of the world increased nearly 5-fold, which also means the number of “outliers” is now also 5-times bigger than it was in 1900. This means that we have a greater chance of finding people more than two standard deviations faster than the average marathon time.

So, with the increasing population of the world, we have a greater chance of finding a world-class performer. But my argument does not stop there…

Not only are there more people but we are also more connected — the space sphere got smaller — or, more accurately, the metaphorical distance that separates us is smaller.

We’d never seen East African athletes on the running scene until the late and great Abebe Bikila from Ethiopia won the Olympic marathon barefoot in Rome in 1960. In Tokyo 1964, Bikila struck marathon gold again as Kenyan Wilson Kiprugut took bronze in the 800m. But the East African floodgate was not truly opened until the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, where East African men, including the great Kip Keino, took gold in the 1500m, 10,000m, 3000m Steeplechase, and the marathon. Since the late 1960s, East African men and women have dominated endurance events. At Rio 2016, athletes from Kenya and Ethiopia won 21 medals in distance events! And, the current middle and long-distance world records are dominated by athletes from East Africa.

Part of this dominance could be attributed to the increased “connectivity” with the world driven by the training camps that were established in the Rift Valley in the 1970s, pioneered by Bruce Tulloh. It's certainly not that athletes from these parts of the globe suddenly got good at running, they are now simply enabled to have running goals besides the necessities of daily living...

Strikingly, average marathon finish times are not improving. In 2020, the Danish statistician and athlete, Jens Jakob Andersen, and his colleague, Vania Nikolova, conducted a wonderful analysis of around 108-million marathon results from ~70,000 races between 1986 and 2018 worldwide (an update to their 2018 analysis). They found that although marathon participation has steadily increased in both men and women and that overseas travel to race a marathon is increasingly common, the average marathon finish time is 40 minutes and 14 seconds slower in 2020 than it was in 1986, slowing from 3:52 to 4:32. To put things in perspective, the current average finish times for men and women (~4:20 and ~4:50) are more than twice as slow as the fastest times — 2:01 for men and 2:14 for women.

There are multiple reasons for the average times getting slower, such as the increase in mass-participation and the shift from physiological goals (getting a PB) to psychological goals (having greater wellbeing from being active, being social, and feeling connected to others). At the top end, however, the best times are still making small inch-worm crawls forward. But, I argue that this is not because “we” are improving as a species but that the size of the “world-class” sample being selected from the population has increased — there is a greater chance of finding really fast people — and, given that there there are fewer barriers to travel and participation, the opportunity for finding the really fast people has gone through the roof.

So, are humans continuing to get faster? Perhaps not. If we strip away the carbon-fibre embedded shoes and side-split flappy short-shorts, perhaps there are simply increasingly more humans and the “world-class” humans are increasingly more accessible.

Thanks for joining me to hear this viewpoint. Until next time, keep thinking outside the box and keep training smart.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Once upon a time, we stood up — Homo erectus — our likely (and also now extinct) ancestor. We evolved to move on hindlimbs. We evolved to run, to “outrun” prey so that we could eat. Running is one of the many attributes that have helped us survive the test of time. But today, our running performance no longer needs to “evolve” because most of us no longer need to outrun lions — to avoid being eaten — or outrun antelope — to avoid being hungry — and those of us who do need these skills are already well-adapted for doing so, otherwise they would not be here.

So, the first important question to consider is...

Are we getting faster?

The current world records in track and road running are way beyond the capabilities of the average human. Indeed some of the world records over the last 12-months have been phenomenal — Eliud Kipchoge’s and Brigid Kosgei’s 2:01 and 2:14 marathons, Ababel Yeshaneh 1:04 half-marathon, Joshua Cheptegei’s 26:11 and 12:35 10,000 and 5000m records, and Letesenbet Gidey’s 14:06 5000m are all incredible.But isolated observations simply tickle our excitement and do not tell us much regarding progress. Examining the trends in world records across the ages reveals some clues. Recently, scientists at Western Michigan University examined the best running performances in distances from 100m to the marathon between 1900 and 2018. They found that performances in all events have made massive improvements but are reaching an asymptote — a physiological peak — in both men and women. Other research has identified the same trends in swimming, race walking, and powerlifting, and shows that world records have reached about 99% of their predicted asymptotes.

Similar work from Giuseppe Lippi at the University of Verona and his colleagues from various universities around the world, found that the time-dependent progression in world record running times over the same timeframe has slowed to a near plateau, concluding that the dramatic advances in times since 1900 “might be explained by a variety of factors, including social and environmental changes, natural selection, advances in training and sport physiology, ergogenic aids and, possibly, doping”.

This conclusion from Lippi and colleagues is a pretty typical comment from observers of trends in improvements in human performance. We certainly cannot deny that there have been advancements in the knowledge of and access to training, supplements, and doping. Plus, there have indeed been sociological advances in sport (for example, more women are choosing to participate and are now allowed to compete in all events), as well as technical progress (for example, Dick Fosbury’s flop or the Shot putters spin) and technological progress (spikes, cushioning, and the most important technological advance ever made in men’s running — the side-split flappy short-shorts). More recently, we also have the moral dilemma of carbon-fibre plated shoes, which sprinkle the most recent records with “technological artefact”, just like the now-banned “LZR” sharkskin suit did in swimming.

×

![]()

So, yes, world record times have indeed gotten quicker albeit at a progressively decreasing rate of improvement.

But, I pose an additional perspective to ponder…

Are there just more of us and are we just more connected?

In 1900, the population of the world was estimated to be around 1.6 billion. Jump forward 120-years and there are an estimated 7.8 billion of us humans roaming this planet. Yes, these are estimates and, yes, there is a range of “probable” values around these estimates but, on average, there has been approximately a 5-fold increase in the number of jolly folks bumbling around our space sphere.For the sake of keeping my argument simple, let’s look at a single event: the marathon… If we assume that marathon running times for everyone in the human population are “normally” distributed — meaning that 50% of times lie above the mean (average) value and 50% lie below the average — then, “outliers” would refer to marathon times that are more than two standard deviations away from the average marathon time. Without delving into the maths, this would mean that approximately 5% of times will be an “outlier” — 2.5% above (“world-class”) and 2.5% below (“terribly slow”). If the size of the population gets larger, so too does the number of people within the “outlier” regions of the normal distribution of times.

Between 1900 and 2020, the population of the world increased nearly 5-fold, which also means the number of “outliers” is now also 5-times bigger than it was in 1900. This means that we have a greater chance of finding people more than two standard deviations faster than the average marathon time.

So, with the increasing population of the world, we have a greater chance of finding a world-class performer. But my argument does not stop there…

Not only are there more people but we are also more connected — the space sphere got smaller — or, more accurately, the metaphorical distance that separates us is smaller.

We’d never seen East African athletes on the running scene until the late and great Abebe Bikila from Ethiopia won the Olympic marathon barefoot in Rome in 1960. In Tokyo 1964, Bikila struck marathon gold again as Kenyan Wilson Kiprugut took bronze in the 800m. But the East African floodgate was not truly opened until the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, where East African men, including the great Kip Keino, took gold in the 1500m, 10,000m, 3000m Steeplechase, and the marathon. Since the late 1960s, East African men and women have dominated endurance events. At Rio 2016, athletes from Kenya and Ethiopia won 21 medals in distance events! And, the current middle and long-distance world records are dominated by athletes from East Africa.

Part of this dominance could be attributed to the increased “connectivity” with the world driven by the training camps that were established in the Rift Valley in the 1970s, pioneered by Bruce Tulloh. It's certainly not that athletes from these parts of the globe suddenly got good at running, they are now simply enabled to have running goals besides the necessities of daily living...

Strikingly, average marathon finish times are not improving. In 2020, the Danish statistician and athlete, Jens Jakob Andersen, and his colleague, Vania Nikolova, conducted a wonderful analysis of around 108-million marathon results from ~70,000 races between 1986 and 2018 worldwide (an update to their 2018 analysis). They found that although marathon participation has steadily increased in both men and women and that overseas travel to race a marathon is increasingly common, the average marathon finish time is 40 minutes and 14 seconds slower in 2020 than it was in 1986, slowing from 3:52 to 4:32. To put things in perspective, the current average finish times for men and women (~4:20 and ~4:50) are more than twice as slow as the fastest times — 2:01 for men and 2:14 for women.

There are multiple reasons for the average times getting slower, such as the increase in mass-participation and the shift from physiological goals (getting a PB) to psychological goals (having greater wellbeing from being active, being social, and feeling connected to others). At the top end, however, the best times are still making small inch-worm crawls forward. But, I argue that this is not because “we” are improving as a species but that the size of the “world-class” sample being selected from the population has increased — there is a greater chance of finding really fast people — and, given that there there are fewer barriers to travel and participation, the opportunity for finding the really fast people has gone through the roof.

So, are humans continuing to get faster? Perhaps not. If we strip away the carbon-fibre embedded shoes and side-split flappy short-shorts, perhaps there are simply increasingly more humans and the “world-class” humans are increasingly more accessible.

Thanks for joining me to hear this viewpoint. Until next time, keep thinking outside the box and keep training smart.

×

![]()

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.