Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — What is fatigue?

→ Part 2 — Do your muscles slow you down?

→ Part 3 — Does your brain slow you down?

→ Part 4 — Why do you slow down?

→ Part 5 — How to resist slowing down.

→ Part 6 — There’s always something left in the tank.

→ Part 1 — What is fatigue?

→ Part 2 — Do your muscles slow you down?

→ Part 3 — Does your brain slow you down?

→ Part 4 — Why do you slow down?

→ Part 5 — How to resist slowing down.

→ Part 6 — There’s always something left in the tank.

Fatigue in runners. Part 4 of 6:

What causes fatigue during exercise?

Thomas Solomon PhD.

16th April 2022.

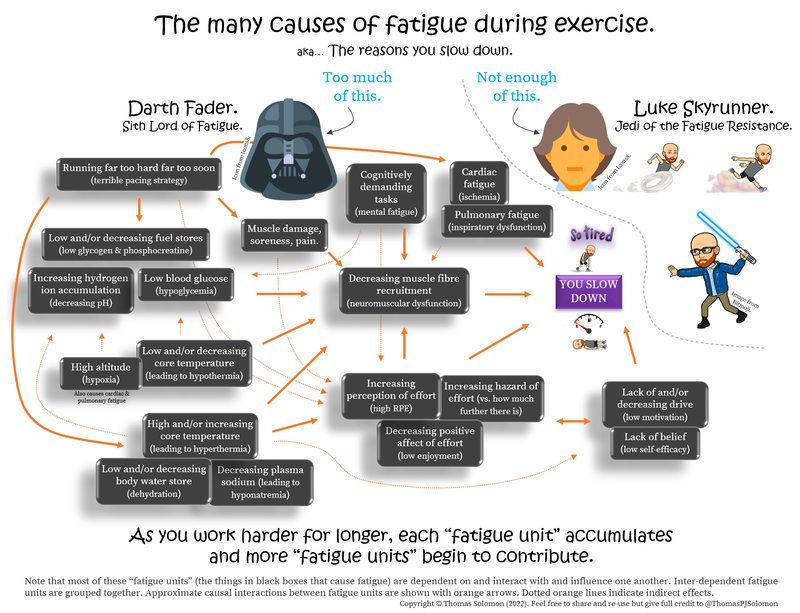

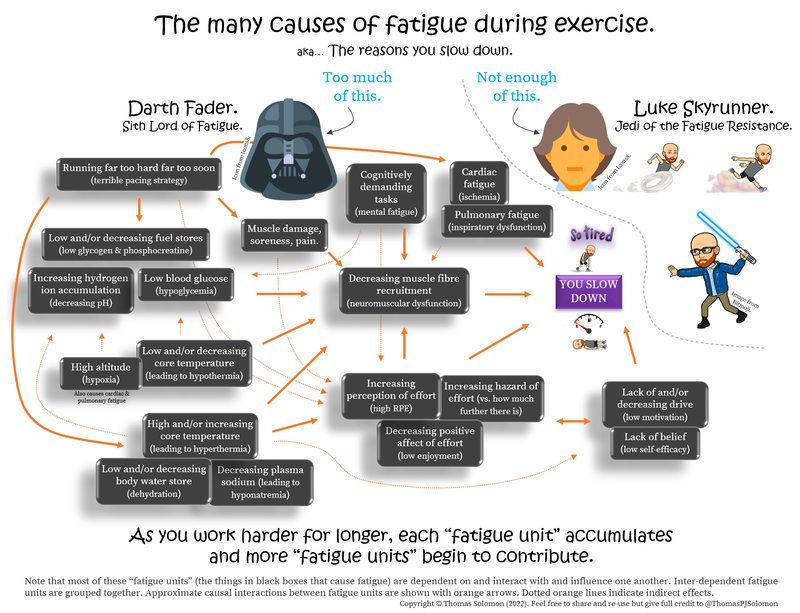

Part 2 and Part 3 dug deep into the mechanistic details of the many theoretical models explaining why you slow you down when you are working hard, including “peripheral” things (in your muscles, heart, and lungs) and “central” things (in your brain). Now it is time to stir everything into the pot and find out what invites a visit from Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue , on race day. So, if you’re less interested in the why and more interested in the what, this part is for you…

, on race day. So, if you’re less interested in the why and more interested in the what, this part is for you…

Reading time ~10-mins (2000-words).

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

I think of fatigue during exercise as your legs saying “Yeah, let’s do this!” and your brain saying “Yeah… but nah.”. Now I’ve gone deep on the many routes to fatigue, you probably realise that while a large part of the physiology of fatigue manifests in your muscles (and heart and lungs, etc), an equally large part of fatigue develops in your brain to include your (neuro)physiology (nerve impulses), psychology (motivation and belief), and emotions (feelings). Some scientists even argue that fatigue during exercise is an emotional state not a physical event because your perceived feeling of exertion (RPE) steadily increases to a maximum, at which point you slow down and stop. But, the reality is that...

Sometimes, limitations in your muscles, heart, and lungs slow you down.

Sometimes, limitations in your muscles, heart, and lungs slow you down.

Sometimes, your lack of resilience to environmental extremes slows you down.

Sometimes, your lack of resilience to environmental extremes slows you down.

Sometimes, your brain makes you slow down.

Sometimes, your brain makes you slow down.

Other times, you choose to slow down.

Other times, you choose to slow down.

Fatigue is caused by the depletion of energy. Fatigue is caused by the accumulation of metabolites that decrease the ability to utilise chemical energy and decrease muscle contractility. Fatigue is caused by damage to structural proteins (in muscle and tendons) that impair biomechanics and cause soreness and pain. Fatigue is caused by hyperthermia (high core body temperature) and hypoxia (low atmospheric oxygen). All these things are sensed by the brain, which integrates these signals with your level of motivation and self-belief and feelings of perceived exertion to alter your work output ultimately protecting the body from damage. So,

Your pace adjustment “choices” during a race may be conscious or subconscious and involve your body and mind and all that’s around you…

Your pace adjustment “choices” during a race may be conscious or subconscious and involve your body and mind and all that’s around you…

It's a complex decision-making process involving physiological, psychological, environmental, and tactical information.

It's a complex decision-making process involving physiological, psychological, environmental, and tactical information.

In Part 2 and Part 3 you learned about the several distinct “models” of fatigue and that scientists have “tidied” them into two distinct halves: peripheral and central fatigue. But your races (and sessions) are not tidy laboratory experiments — it is highly unlikely that the distinct models work in isolation nor that peripheral and central fatigue are truly segregated. During your races, all these “things” — hypoglycemia, low glycogen, metabolic acidosis, rising body temperature, eccentric muscle damage, soreness/pain, neuromuscular dysfunction, poor central drive, low motivation, low belief, etc — are simultaneously smashing your homeostasis. For that reason, it is almost always impossible to assign one factor as the sole cause of your failed performance on race day. You must think broadly… Was it because of:

Pre-existing or increasing muscle damage, and/or soreness, and/or pain.

Pre-existing or increasing muscle damage, and/or soreness, and/or pain.

Decreasing muscle fibre recruitment (aka neuromuscular dysfunction; leading to less force production.

Decreasing muscle fibre recruitment (aka neuromuscular dysfunction; leading to less force production.

Low and/or decreasing fuel stores (glycogen and/or phosphocreatine depletion).

Low and/or decreasing fuel stores (glycogen and/or phosphocreatine depletion).

Increasing hydrogen ion (H+) accumulation (aka metabolic acidosis due to low pH).

Increasing hydrogen ion (H+) accumulation (aka metabolic acidosis due to low pH).

Low blood glucose concentration (aka hypoglycemia).

Low blood glucose concentration (aka hypoglycemia).

High and/or increasing core temperature (leading to decreased thermal comfort and hyperthermia). Or, on the flip side, low and/or decreasing core temperature (leading to hypothermia).

High and/or increasing core temperature (leading to decreased thermal comfort and hyperthermia). Or, on the flip side, low and/or decreasing core temperature (leading to hypothermia).

Low and/or decreasing body water store (aka dehydration) and/or decreasing plasma sodium concentration (leading to hyponatremia).

Low and/or decreasing body water store (aka dehydration) and/or decreasing plasma sodium concentration (leading to hyponatremia).

Low blood oxygen saturation due to hypoxia (“thin air” at altitude) and/or low blood haemoglobin mass (aka anaemia caused by low iron stores and/or blood loss).

Low blood oxygen saturation due to hypoxia (“thin air” at altitude) and/or low blood haemoglobin mass (aka anaemia caused by low iron stores and/or blood loss).

Increasing perception of effort (aka rising RPE), and/or increasing hazard of effort (vs. how much further there is), and/or loss of enjoyment of effort (aka decreasing positive affect).

Increasing perception of effort (aka rising RPE), and/or increasing hazard of effort (vs. how much further there is), and/or loss of enjoyment of effort (aka decreasing positive affect).

Running far too hard far too soon — a terrible pacing strategy causing all of the above to happen far sooner than desired.

Running far too hard far too soon — a terrible pacing strategy causing all of the above to happen far sooner than desired.

Lack of and/or decreasing motivation (aka low drive) and/or lack of belief (aka low self-efficacy). Or,

Lack of and/or decreasing motivation (aka low drive) and/or lack of belief (aka low self-efficacy). Or,

High level of and/or increasing amount of cognitively demanding tasks (leading to mental fatigue and stress) like hearing this list of things.

High level of and/or increasing amount of cognitively demanding tasks (leading to mental fatigue and stress) like hearing this list of things.

And, so on…

These are the many “things” that cause fatigue on race day. It’s like a “pick and mix” — either one, some, or all these factors may be observed at the onset of fatigue. Your ultimate decision to slow down or, worst case, stop, is a result of a wicked network of signals being detected and processed. I think of these things as “fatigue units” — as you work harder for longer, each fatigue unit accumulates and more fatigue units begin to contribute.

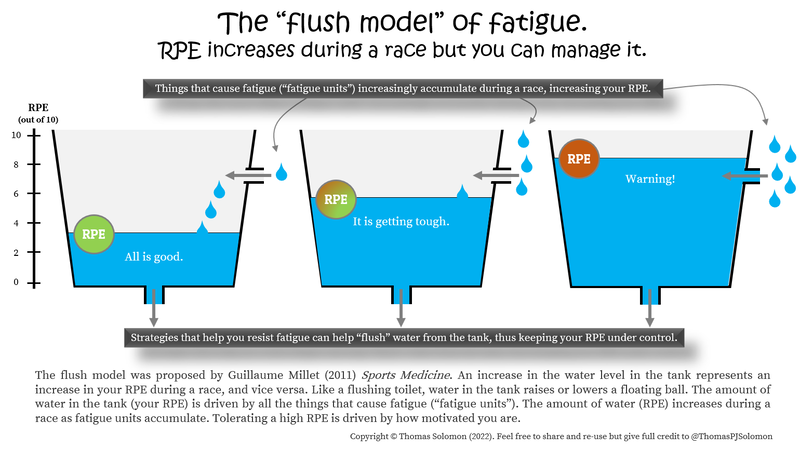

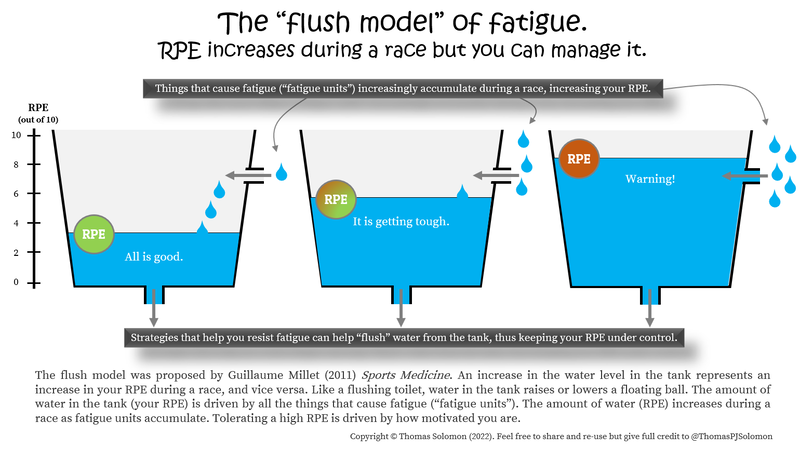

In 2011, Guillaume Millet proposed a “flush” model of fatigue in which your increasing feeling of exertion (RPE) during a race is caused by a combination of both central and peripheral things and external factors like energy availability and weather, etc. In the flush model, Millet uses a metaphor where water in a tank represents RPE. During a race, RPE gradually increases (due to the accumulation of things that I call “fatigue units”) but the rate of increase in RPE can be tempered by “flushing water” out of the tank through a “waste pipe”. This is a nice way to conceptualise fatigue during a race, particularly because it illustrates that increasing RPE can be “managed” and prevented from getting too high. All you need is a selection of the right tools in your fatigue resistance toolbox (more on that in Part 5).

For the first session, I simply shoehorned it into my schedule among my work tasks. I did not target the session and did not think about it until gun time. For the second session 9-days later, I focussed everything on it. I scheduled it in my calendar, I thought about my emotions, I visualised how it would feel, I planned an if-then strategy to overcome the escalating discomfort. Essentially, I treated it like an “A” race.

What happened?

At the start of each session, I felt cool and calm. But, during the warm-up for the first session, the one I had not targeted, my legs did not feel “springy” and I was not excited for the session. As I embarked on the 1-mile push, it hurt — my legs burned, my breathing felt out of control, my RPE shot through the roof, and I was distracted by pedestrians and motorists. I was not “in the zone” and was completely unmotivated. In fact, I “aborted mission” shortly into it — I was apathetic, had zero motivation to push, and zero motivation to complete.

Meanwhile, for the second session, I felt great. The warm-up was fun and springy, and I couldn’t wait for the session — I felt happy and highly motivated to smash. Yes, the efforts hurt and my legs burned but I embraced and enjoyed riding the wave of pain. I felt strong and was able to push hard for the whole session.

These are the many faces of fatigue in action — physiology, psychology, and emotion. Perhaps you can relate to this. If you want to nail a workout or race and unleash your physiological potential, perhaps you need to “emphasise it” and make it matter — perhaps, you need to be highly motivated… Similarly, if you followed Part 1, you will remember Thor’s Hammer test — holding books, cans, or dumbbells out to your sides, parallel to the ground, for as long as possible. Try it. Notice the level of effort compared to how hard you thought it would be. Notice your sensations of muscular discomfort and pain. Notice your desire to end. Notice your motivation to continue. It’s like a race — giving it large and then trying to continue giving it large when things get tough. Naturally, if you are strong you’ll be pretty good at Thor’s Hammer. If you have specifically trained for Strongman, you’ll be really good. But also remember that you will tolerate more discomfort and enjoy a higher RPE for longer when you are highly motivated, believe you can, and highly value the goal. Thor’s Hammers reveal many of the things you need to train to win on race day.

.

.

In my experience as an athlete and a coach, during long-duration high-intensity races (including half-marathons, full marathons, trail races, mountains races, and obstacle course races), raceday “post-mortems” typically identify that poor race day nutrition (starting with and maintaining low carbohydrate availability) and/or an overly ambitious race strategy (starting out way too hard) and/or starting the race with mental fatigue (from cognitively-demanding tasks) are present when an athlete gets a race day visit from Lord Fader. But, remember, a race-day fade can be caused by poor pacing decisions, muscle damage, soreness/pain, glycogen depletion, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, hyperthermia or hypothermia, dehydration, mental fatigue and stress, lack of motivation, lack of belief, etc etc.

In endurance racing, “fatigue resistance” is what separates champions from losers. But, the mechanisms of fatigue are complex and not entirely understood, and, in some cases, like the central governor theory, largely theoretical. Therefore, it is difficult to know exactly how to plan and design your training and/or which racing strategies to use to help you delay a visit from Lord Fader.

Well, that sounds pessimistic!

Fear not… The glass of fatigue units is half full and Luke Skyrunner can help you become a Master of the Fatigue Resistance by encouraging you to think like a Jedi… Ask yourself the following questions:

can help you become a Master of the Fatigue Resistance by encouraging you to think like a Jedi… Ask yourself the following questions:

Did your training under-prepare you for the duration, intensity, and technicality of the race?

Did your training under-prepare you for the duration, intensity, and technicality of the race?

Did you run far too hard far too soon during the race (terrible pacing)?

Did you run far too hard far too soon during the race (terrible pacing)?

Did you start the race with low carbohydrate availability (glycogen depleted)?

Did you start the race with low carbohydrate availability (glycogen depleted)?

Did you start the race feeling thirsty and/or craving salt?

Did you start the race feeling thirsty and/or craving salt?

Did you start the race feeling heavy-legged and sluggish and/or sore?

Did you start the race feeling heavy-legged and sluggish and/or sore?

Did you start the race feeling tired or having been under unusual levels of stress?

Did you start the race feeling tired or having been under unusual levels of stress?

Did you complete an epic Frodo-like journey to get to the race venue?

Did you complete an epic Frodo-like journey to get to the race venue?

If the race was “high”, hot, or cold, did you fail to use acclimation strategies before the race?

If the race was “high”, hot, or cold, did you fail to use acclimation strategies before the race?

If it was hot, did you fail to keep cool before and during the race?

If it was hot, did you fail to keep cool before and during the race?

If it was cold, did you fail to keep warm before and during the race?

If it was cold, did you fail to keep warm before and during the race?

If it was a long race, did you fail to maintain high carb availability (eat carbs) during the race?

If it was a long race, did you fail to maintain high carb availability (eat carbs) during the race?

If it was a long race and if it was hot, did you fail to drink any fluid to quench your thirst during the race?

If it was a long race and if it was hot, did you fail to drink any fluid to quench your thirst during the race?

During the race, did you develop signs of damage (soreness and/or pain) in your muscles or joints?

During the race, did you develop signs of damage (soreness and/or pain) in your muscles or joints?

Did the hard effort feel terrible during the race? Were you unmotivated to push hard during the race? Did you lack the belief that you could push hard during the race?

Did the hard effort feel terrible during the race? Were you unmotivated to push hard during the race? Did you lack the belief that you could push hard during the race?

Answering yes to any one of these questions adds a “fatigue unit” to the list of possible causes of your race-day visit from Lord Fader. Using this framework will help inform your training and racing decisions to become the best athlete you can be.

It is clear that several factors (“fatigue units”) contribute to slowing you down during exercise and all of them are also influenced by what you have done recently — i.e. your underlying feeling of fatigue when you start a session or race is also determined by accumulated physical and/or mental fatigue and by your nutritional and hydration status etc. For these reasons, resisting fatigue is indeed a complex problem but a problem for which a solution is found via many routes. But that will have to wait until Part 5... Until that time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I am passionate about equality in access to free education. If you find value in my content, please help keep it alive by sharing it on social media and buying me a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join me @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to my free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out my other Articles, Nerd Alerts, Free Training Tools, and my Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to my articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

And, so on…

×

![]()

In 2011, Guillaume Millet proposed a “flush” model of fatigue in which your increasing feeling of exertion (RPE) during a race is caused by a combination of both central and peripheral things and external factors like energy availability and weather, etc. In the flush model, Millet uses a metaphor where water in a tank represents RPE. During a race, RPE gradually increases (due to the accumulation of things that I call “fatigue units”) but the rate of increase in RPE can be tempered by “flushing water” out of the tank through a “waste pipe”. This is a nice way to conceptualise fatigue during a race, particularly because it illustrates that increasing RPE can be “managed” and prevented from getting too high. All you need is a selection of the right tools in your fatigue resistance toolbox (more on that in Part 5).

×

![]()

Putting fatigue into practice.

When I started putting this series together (which, I admit, was about a year ago and I got distracted with another topic), I completed two identical sessions 9-days apart. Each session started with my standard warm-up of activation exercises, progressive effort running, some drills, and some strides. Then I unleashed the session: a hard 1-mile effort followed by 4 × (1-min hard, 1-min Easy). During the 3-days preceding each workout, I had slept consistently (~7 h/night; quality 4/5), eaten well, and felt fresh and ready-to-go, having only done easy-effort (RPE less than 5/10), short duration (less than 60-mins) workouts each day. Both sessions were completed 2½ hours after a ~400 kcal meal containing ~60 grams of carbohydrate to ensure similar liver glycogen levels and stable blood glucose, and the conditions were similar on both days — ~5°C (~40°F), ~60% relative humidity, dry, and calm. The specific purpose of the session was to take my body and mind to the well — to induce fatigue. And, conditions surrounding the two sessions were as identical as they could be, except for one important caveat…For the first session, I simply shoehorned it into my schedule among my work tasks. I did not target the session and did not think about it until gun time. For the second session 9-days later, I focussed everything on it. I scheduled it in my calendar, I thought about my emotions, I visualised how it would feel, I planned an if-then strategy to overcome the escalating discomfort. Essentially, I treated it like an “A” race.

What happened?

At the start of each session, I felt cool and calm. But, during the warm-up for the first session, the one I had not targeted, my legs did not feel “springy” and I was not excited for the session. As I embarked on the 1-mile push, it hurt — my legs burned, my breathing felt out of control, my RPE shot through the roof, and I was distracted by pedestrians and motorists. I was not “in the zone” and was completely unmotivated. In fact, I “aborted mission” shortly into it — I was apathetic, had zero motivation to push, and zero motivation to complete.

Meanwhile, for the second session, I felt great. The warm-up was fun and springy, and I couldn’t wait for the session — I felt happy and highly motivated to smash. Yes, the efforts hurt and my legs burned but I embraced and enjoyed riding the wave of pain. I felt strong and was able to push hard for the whole session.

These are the many faces of fatigue in action — physiology, psychology, and emotion. Perhaps you can relate to this. If you want to nail a workout or race and unleash your physiological potential, perhaps you need to “emphasise it” and make it matter — perhaps, you need to be highly motivated… Similarly, if you followed Part 1, you will remember Thor’s Hammer test — holding books, cans, or dumbbells out to your sides, parallel to the ground, for as long as possible. Try it. Notice the level of effort compared to how hard you thought it would be. Notice your sensations of muscular discomfort and pain. Notice your desire to end. Notice your motivation to continue. It’s like a race — giving it large and then trying to continue giving it large when things get tough. Naturally, if you are strong you’ll be pretty good at Thor’s Hammer. If you have specifically trained for Strongman, you’ll be really good. But also remember that you will tolerate more discomfort and enjoy a higher RPE for longer when you are highly motivated, believe you can, and highly value the goal. Thor’s Hammers reveal many of the things you need to train to win on race day.

What can you put in your fatigue toolbox?

What causes you to slow down and stop? Is it peripheral fatigue, central fatigue, perception of effort? It’s hard to say. Does the specific reason matter? Probably not. Why not? Because as I’ve mentioned before, fatigue during exercise is a complicated soup of many things — it is almost always impossible to assign a single “fatigue unit” as the sole cause of your race day visit from Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigueIn my experience as an athlete and a coach, during long-duration high-intensity races (including half-marathons, full marathons, trail races, mountains races, and obstacle course races), raceday “post-mortems” typically identify that poor race day nutrition (starting with and maintaining low carbohydrate availability) and/or an overly ambitious race strategy (starting out way too hard) and/or starting the race with mental fatigue (from cognitively-demanding tasks) are present when an athlete gets a race day visit from Lord Fader. But, remember, a race-day fade can be caused by poor pacing decisions, muscle damage, soreness/pain, glycogen depletion, metabolic acidosis, hypoglycemia, hyperthermia or hypothermia, dehydration, mental fatigue and stress, lack of motivation, lack of belief, etc etc.

In endurance racing, “fatigue resistance” is what separates champions from losers. But, the mechanisms of fatigue are complex and not entirely understood, and, in some cases, like the central governor theory, largely theoretical. Therefore, it is difficult to know exactly how to plan and design your training and/or which racing strategies to use to help you delay a visit from Lord Fader.

Well, that sounds pessimistic!

Fear not… The glass of fatigue units is half full and Luke Skyrunner

It is clear that several factors (“fatigue units”) contribute to slowing you down during exercise and all of them are also influenced by what you have done recently — i.e. your underlying feeling of fatigue when you start a session or race is also determined by accumulated physical and/or mental fatigue and by your nutritional and hydration status etc. For these reasons, resisting fatigue is indeed a complex problem but a problem for which a solution is found via many routes. But that will have to wait until Part 5... Until that time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I am passionate about equality in access to free education. If you find value in my content, please help keep it alive by sharing it on social media and buying me a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join me @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to my free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out my other Articles, Nerd Alerts, Free Training Tools, and my Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to my articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.