Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — What is fatigue?

→ Part 2 — Do your muscles slow you down?

→ Part 3 — Does your brain slow you down?

→ Part 4 — Why do you slow down?

→ Part 5 — How to resist slowing down.

→ Part 6 — There’s always something left in the tank.

→ Part 1 — What is fatigue?

→ Part 2 — Do your muscles slow you down?

→ Part 3 — Does your brain slow you down?

→ Part 4 — Why do you slow down?

→ Part 5 — How to resist slowing down.

→ Part 6 — There’s always something left in the tank.

Fatigue in runners. Part 1 of 6:

What is fatigue?

Thomas Solomon PhD.

26th March 2022.

This 6-part series on fatigue in runners is ultimately designed to help you understand how to resist fatigue during your races. To achieve that goal, I start at the basics and try to unravel what fatigue is… And, by “fatigue”, I do not mean chronic fatigue or overtraining syndrome or feeling tired. I am referring to the kind of fatigue that causes you to eventually slow down when you are working hard.

Reading time ~14-mins (2800-words).

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Meet Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue  . Fader likes to drag you down into the darkness when you least want it. As an athlete, resisting fatigue is your primary goal and no athlete wants to turn to the Darkside. Understanding fatigue is the solution… Now meet Luke Skyrunner, Jedi Master of the Fatigue Resistance

. Fader likes to drag you down into the darkness when you least want it. As an athlete, resisting fatigue is your primary goal and no athlete wants to turn to the Darkside. Understanding fatigue is the solution… Now meet Luke Skyrunner, Jedi Master of the Fatigue Resistance  . Luke can help you learn how to resist fatigue. But before we get there, I want to help you understand what fatigue is and, more importantly, what causes it.

. Luke can help you learn how to resist fatigue. But before we get there, I want to help you understand what fatigue is and, more importantly, what causes it.

Why?

Because this is incredibly important for maximising your performance — it is fundamental. Understanding why you slow down will ultimately help you plan and design your training and use strategies that help you resist fatigue for as long as possible during your races. When we have a bad race, it is oh-so-easy to use our inherent availability bias to blame our visit from Lord Fader on a specific detail that jumps to mind. As you’ll discover in this series, there are multiple causes of fatigue. My goal is to help you build a “fatigue checklist” on which you can systematically ensure you tick every box. So…

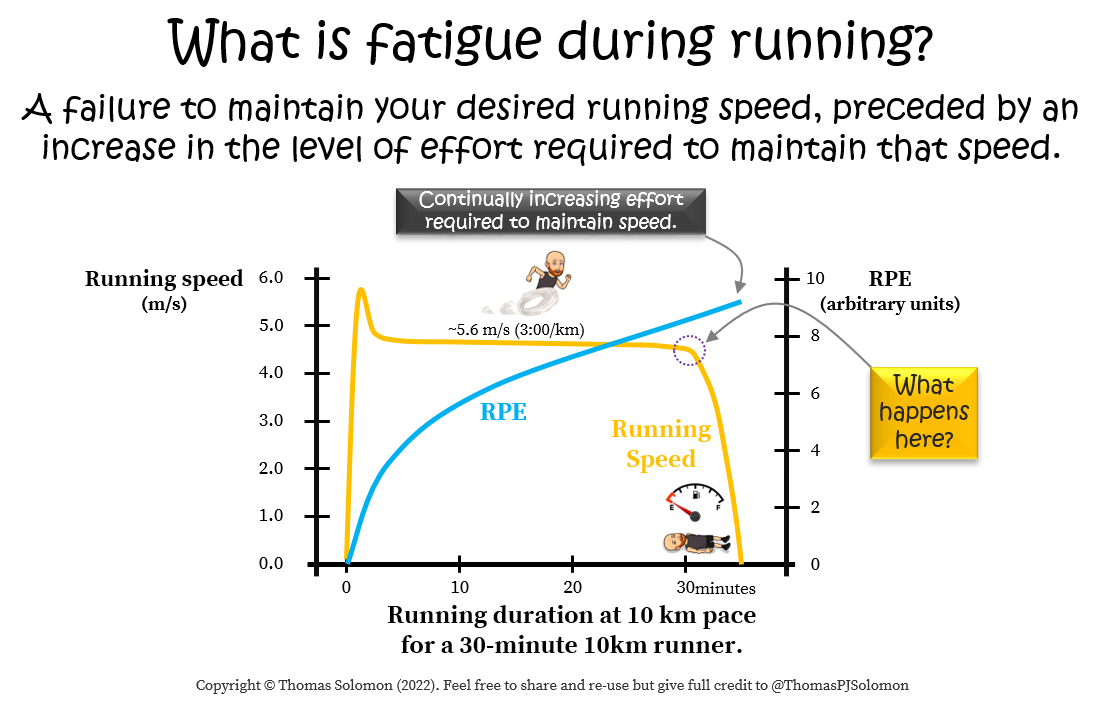

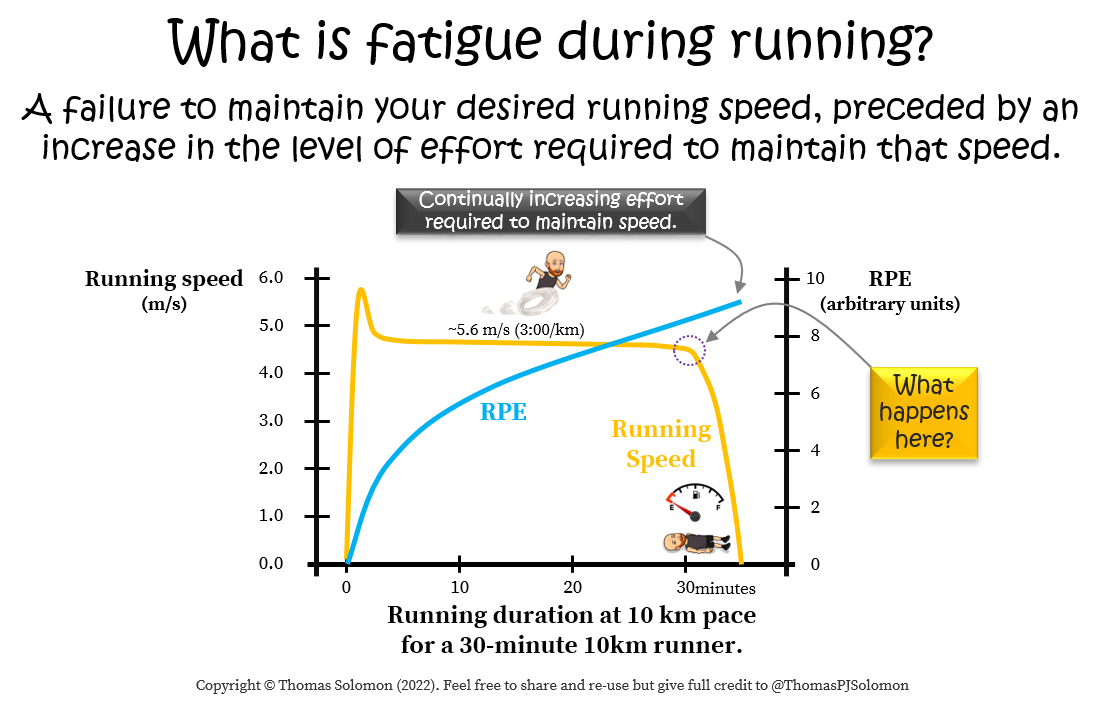

From a physiological perspective, fatigue is commonly defined as an exercise-induced reduction in maximal voluntary muscle force — a failure to maintain expected force (or expected rate of force development, aka power). This can be conceptualised as, for example, your loss of maximal sprinting speed after a long hard run. But, this failure in maximal force is also always preceded by an increase in the level of effort required to maintain that force. Plus, fatigue is not only about maximal force but also a failure to maintain submaximal efforts for long periods — you are probably familiar with the feeling of increased effort required to maintain speed when you start to lose speed. Anyone who has raced long distances will also know that fatigue is also associated with a loss of cognitive ability and skill (decreased motor function).

As you can see, fatigue during exercise marries your physiology with your psychology and feelings (or emotions). I like to think of fatigue as your legs saying “Yeah, let’s do this!” and your brain saying “Yeah… but nah”. And I will dig into what that really means in this series.

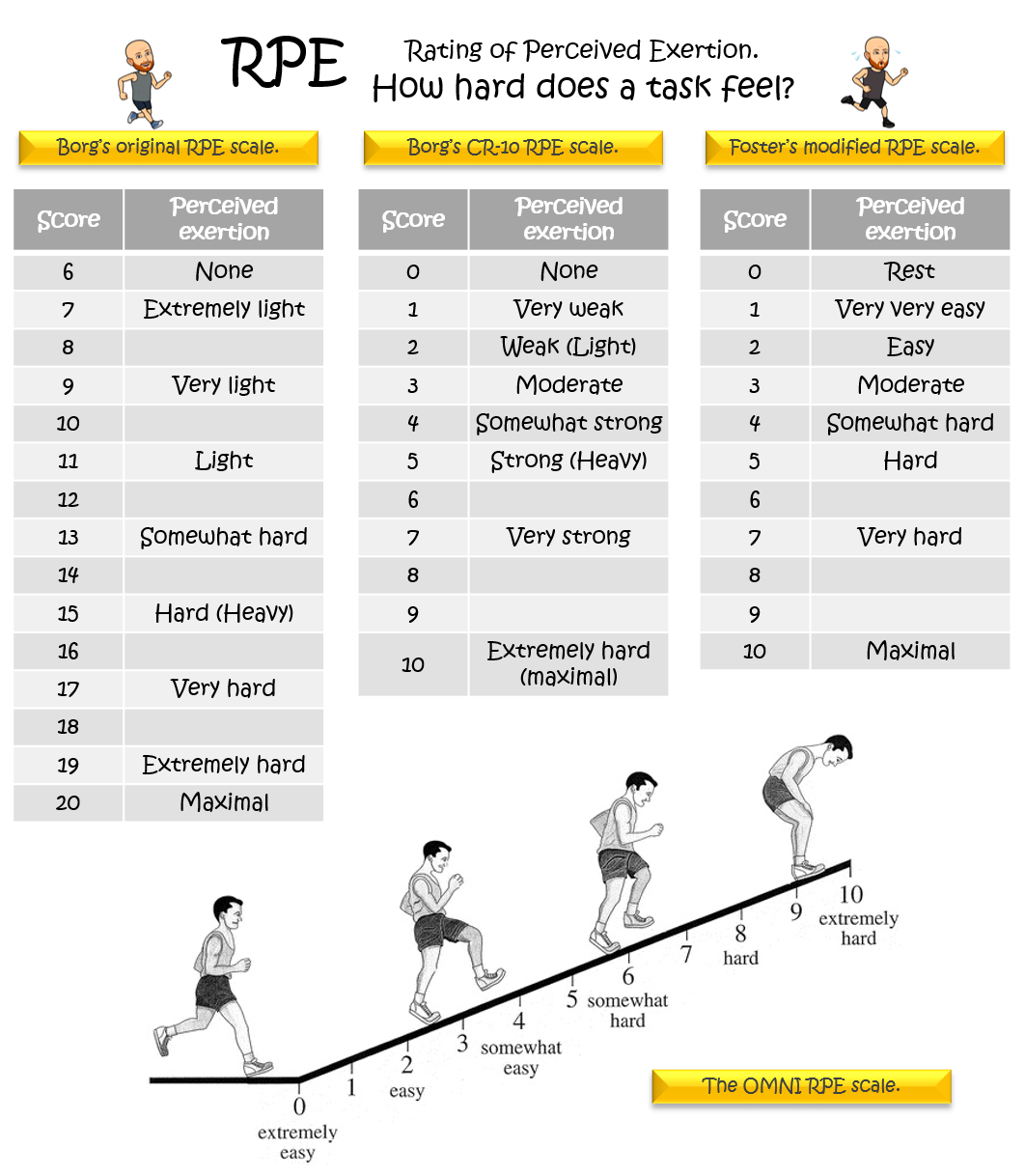

In the 1960s, Gunnar Borg of “Borg Scale” fame applied the “perceived effort” concept to physical work, noting that we are not simply machines; we also show “feelings” of exhaustion related to physical effort. (If you are wondering, no, Gunnar Borg did not invent cyborgs, which are machines that do not have feelings.) Borg’s acknowledgement of “feelings” has become a major part of our understanding of the psychophysiological basis for perceived exertion and no doubt you are familiar with the original 20-point Borg scale rating of perceived exertion (RPE) and/or the subsequent 10-category ratio (the CR-10) RPE scale. If this is news to you, RPE is essentially asking yourself how hard a task feels — “what is my level of exertion right now?”. Pretty simple.

. But if you know you have done the work to make this happen, you will know you are a worthy Jedi of the Fatigue Resistance and can win

. But if you know you have done the work to make this happen, you will know you are a worthy Jedi of the Fatigue Resistance and can win ! Plus, self-efficacy also influences your enjoyment of effort (see here) — on a start line you might believe you will do well until you discover everyone in the race is way faster than you. Shit.

! Plus, self-efficacy also influences your enjoyment of effort (see here) — on a start line you might believe you will do well until you discover everyone in the race is way faster than you. Shit.

So, why on Earth did I tell you about all of it?

Because, as you will discover in Part 2 and Part 3, these concepts will eventually form a foundation of your “how to resist fatigue” checklist.

Now you know what fatigue is, it's a good time to discuss the wicked ways fatigue rears its ugly head… So,

How does Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue

Going deep on race day tests all your physiological, psychological, and emotional attributes and pushes you towards your metabolic, cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular, nutritional, thermoregulatory, psychological, and emotional capacities. If you cannot resist fatigue, you feel more discomfort, you feel less springy, and you slow down as things feel harder. “I have you now, Obi wan.”, Darth Fader would say.

So, how does fatigue present itself on race day?

One of the most amusing things in exercise science is a 2013 paper presenting the stages of collapse during fatigue in runners, aka the “Foster collapse”. For me, dramatic collapses are stereotypical of the finish line mayhem in Decathlon/Heptathlon 800m/1500m races, xc-ski races, and Laura Muir at the end of any race she ever does. Anyone who has ever “bonked” on a long run, or failed a set of lifts or pull-ups, or developed so much “arm pump” that you can no longer hang on a wall or swing through an OCR rig, has experienced some kind of “collapse”. If you have not, fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on perspective), some incredible detonations have been captured live during world-class championships events.

There is the classic Sian Welch & Wendy Ingraham “full Foster” crawl to become Iron(wo)man. Gabriela Andersen-Schiess stumbling to marathon completion at the 1984 Olympics in LA. We’ve seen Paula Newby Fraser collapse at Ironman World Champs 2005. In 2016, we saw Jonny Brownlee’s complete detonation when his brother had to carry him to the finish at a World Cup triathlon race. In 2017, we saw Joshua Cheptegai assuredly on his way to gold at the World Cross Country champs in front of his ecstatic home crowd in Uganda, only to completely detonate in the final km. Callum Hawkins lost gold when he collapsed at the 2018 Commonwealth Games marathon in Australia. And, in Tokyo 2020, the Brazilian runner, Daniel Do Nascimento, had multiple collapses until his eventual DNF in the Olympic marathon. World-class athletes are not immune to fatigue; they just move faster and resist fatigue for longer.

Perhaps you tried to run at Kipchoge pace on a treadmill and slowed down rapidly — this is fatigue. Maybe you’ve experienced a race-day (or during-session) TNT-like detonation — a sudden bonk — or a race-day (or during-session) fade — a gradual deterioration in power output. Perhaps you’ve experienced a kinematic/biomechanical deterioration during closing stages of a race — shortening strides, lessening knee lift, or “pedalling in squares” on a bike. Maybe you’ve experienced muscle cramps. Perhaps you’ve encountered heat stress — “I can’t see, I feel like a furnace, I feel sick, and now I am on the ground”. Or maybe cold stress or hypothermia — “I can’t see, I am shivering, I am making silly decisions, and now I am on the ground”. Or perhaps, you’ve lost motivation to push hard during a race — a brain fade, “I just can’t be bothered to push today”. In all scenarios, it feels like your effort is high but progress is poor — you try to give it large but can only give it medium-small.

Essentially… we slow down during prolonged and/or hard efforts to protect the body from damage and complete failure. For example, prolonged exposure to low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) or high core temperature (hyperthermia) can also irreversibly damage nerves and blood vessels. So, maybe Darth Fader isn’t such a bad dude after all. Perhaps the Sith Lord of Fatigue is actually protecting you from permanent damage. That sounds great but let’s be honest, during a race, your goal is to win, not survive.

Fatigue during exercise is slowing down when you don’t expect (or want) to.

Fatigue during exercise is slowing down when you don’t expect (or want) to.

You have probably experienced this and it usually manifests when all the physiological, psychological, and emotional factors simultaneously culminate in a dramatic race-ending, PB-fading, medal-losing visit from Lord Fader.

Fatigue (or slowing down) is related to your level of effort but the level of effort you are willing to make is also related to your feelings of fatigue. When we measure (or attempt to measure) fatigue, it involves a balance of your actual effort, your expected effort, your enjoyment, your motivation, and your self-belief, and as you might by now have realised these things cannot be entirely driven by what is happening in your muscles. If you have come to that conclusion, you are bang on the money and in Part 2 and Part 3 I will go deep on all the various causes of why we slow down when we don’t expect to and least want to — the various causes that invite a visit from the Sith Lord of Fatigue . Until that time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be by training smart.

. Until that time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be by training smart.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I am passionate about equality in access to free education. If you find value in my content, please help keep it alive by sharing it on social media and buying me a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join me @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to my free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out my other Articles, Nerd Alerts, Free Training Tools, and my Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to my articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Why?

Because this is incredibly important for maximising your performance — it is fundamental. Understanding why you slow down will ultimately help you plan and design your training and use strategies that help you resist fatigue for as long as possible during your races. When we have a bad race, it is oh-so-easy to use our inherent availability bias to blame our visit from Lord Fader on a specific detail that jumps to mind. As you’ll discover in this series, there are multiple causes of fatigue. My goal is to help you build a “fatigue checklist” on which you can systematically ensure you tick every box. So…

What is fatigue?

The classic textbook definition of fatigue was proposed by Richard Edwards in 1981:From a physiological perspective, fatigue is commonly defined as an exercise-induced reduction in maximal voluntary muscle force — a failure to maintain expected force (or expected rate of force development, aka power). This can be conceptualised as, for example, your loss of maximal sprinting speed after a long hard run. But, this failure in maximal force is also always preceded by an increase in the level of effort required to maintain that force. Plus, fatigue is not only about maximal force but also a failure to maintain submaximal efforts for long periods — you are probably familiar with the feeling of increased effort required to maintain speed when you start to lose speed. Anyone who has raced long distances will also know that fatigue is also associated with a loss of cognitive ability and skill (decreased motor function).

As you can see, fatigue during exercise marries your physiology with your psychology and feelings (or emotions). I like to think of fatigue as your legs saying “Yeah, let’s do this!” and your brain saying “Yeah… but nah”. And I will dig into what that really means in this series.

×

![]()

The next obvious question is…

How do we monitor fatigue during exercise?

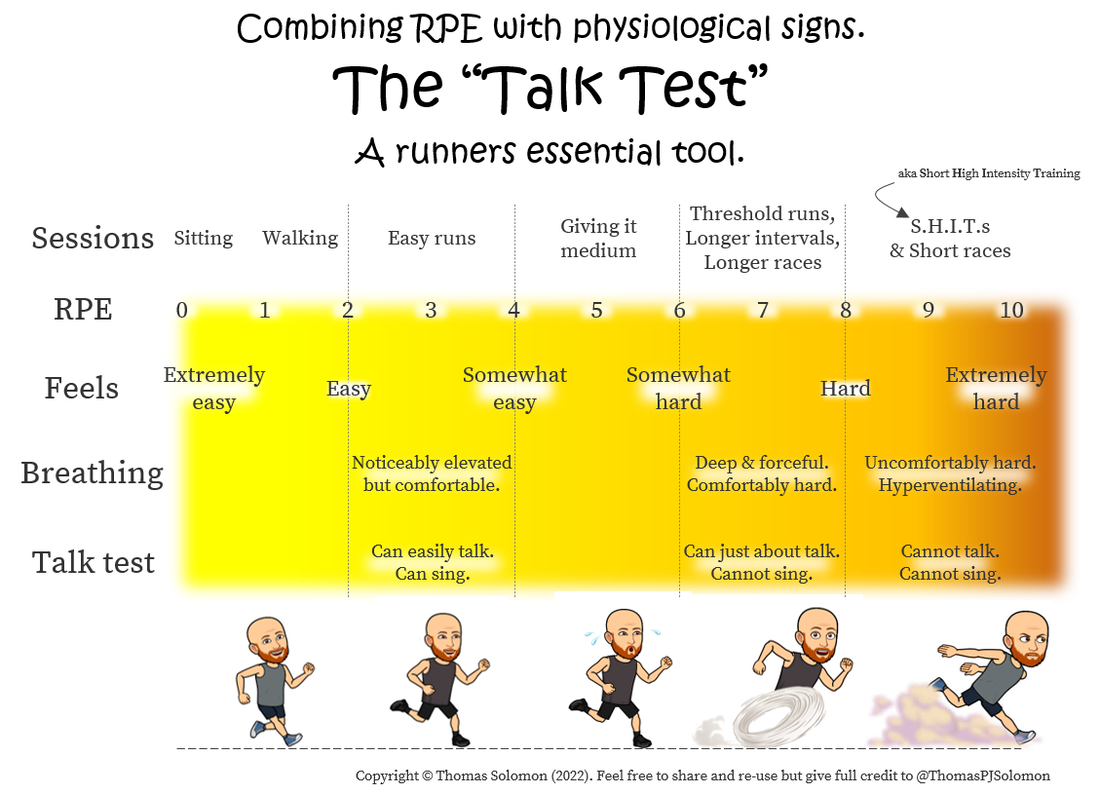

You have probably reached the rather intuitive conclusion that your level of effort during a race (or session) is proportional to your level of fatigue. But, it is equally true that your level of fatigue influences your level of effort. And so, things are already “chicken and egging” out of control. But, don’t worry about that for now…In the 1960s, Gunnar Borg of “Borg Scale” fame applied the “perceived effort” concept to physical work, noting that we are not simply machines; we also show “feelings” of exhaustion related to physical effort. (If you are wondering, no, Gunnar Borg did not invent cyborgs, which are machines that do not have feelings.) Borg’s acknowledgement of “feelings” has become a major part of our understanding of the psychophysiological basis for perceived exertion and no doubt you are familiar with the original 20-point Borg scale rating of perceived exertion (RPE) and/or the subsequent 10-category ratio (the CR-10) RPE scale. If this is news to you, RPE is essentially asking yourself how hard a task feels — “what is my level of exertion right now?”. Pretty simple.

×

![]()

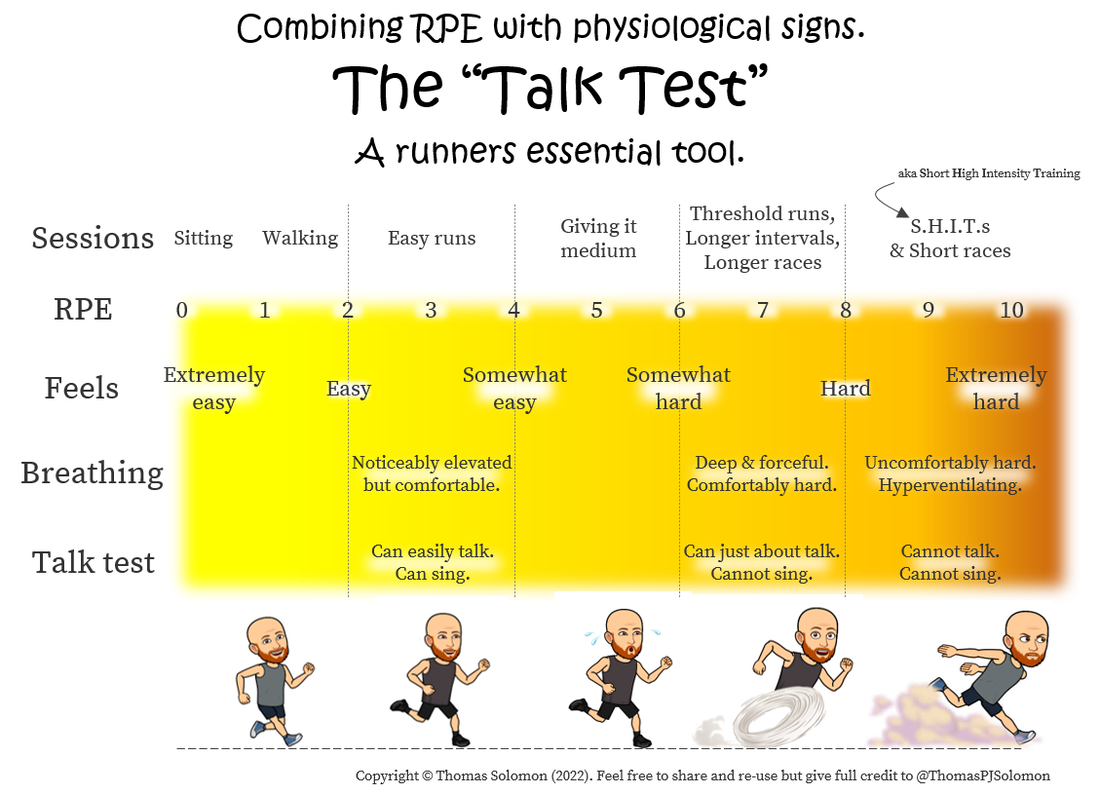

In the early 2000s, Carl Foster and colleagues developed a new approach — the session-RPE, where athletes rate the average intensity of their sessions to help monitor and quantify training load. In doing so, Foster modified the verbal anchors used in the original Borg scale — using “easy” instead of “light” and “hard” instead of “strong” — to help make it more applicable to general exercise. This was further modified with the OMNI RPE scale to provide context to what Easy and Hard feels like specifically during running. In brief, an RPE of 1 is basically sitting down, anything less than 5/10 is “easy effort” exercise, RPE 6 to 8/10 would be equivalent to approaching your critical speed (10km to half marathon pace — “giving it medium large”), anything 8 or above is “giving it large”, and RPE 10/10 is an extremely hard maximal effort (e.g. a sprint race or a sprint for the line).

×

![]()

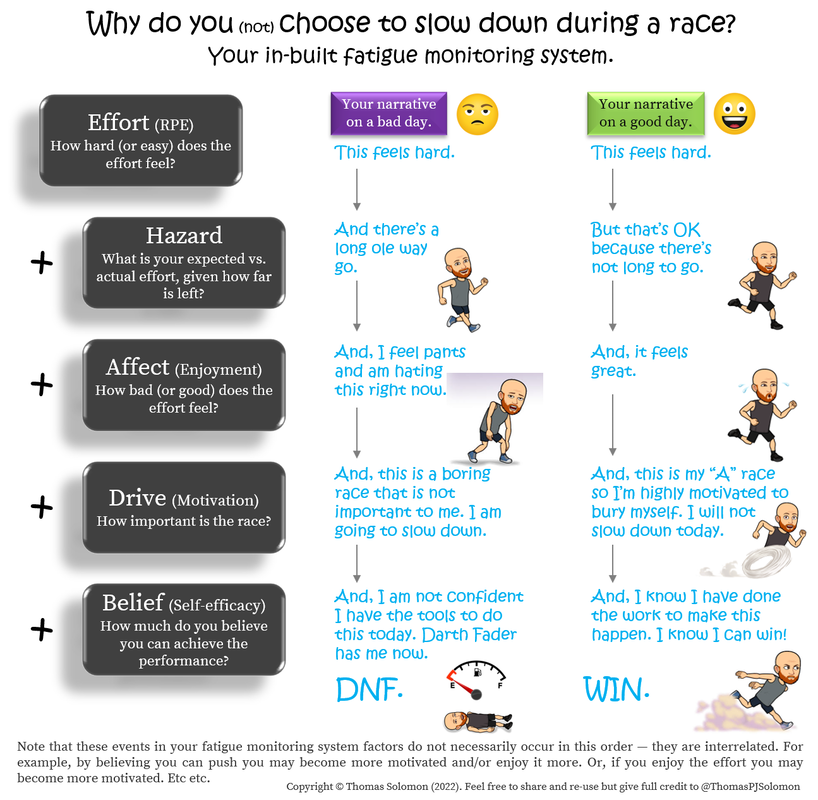

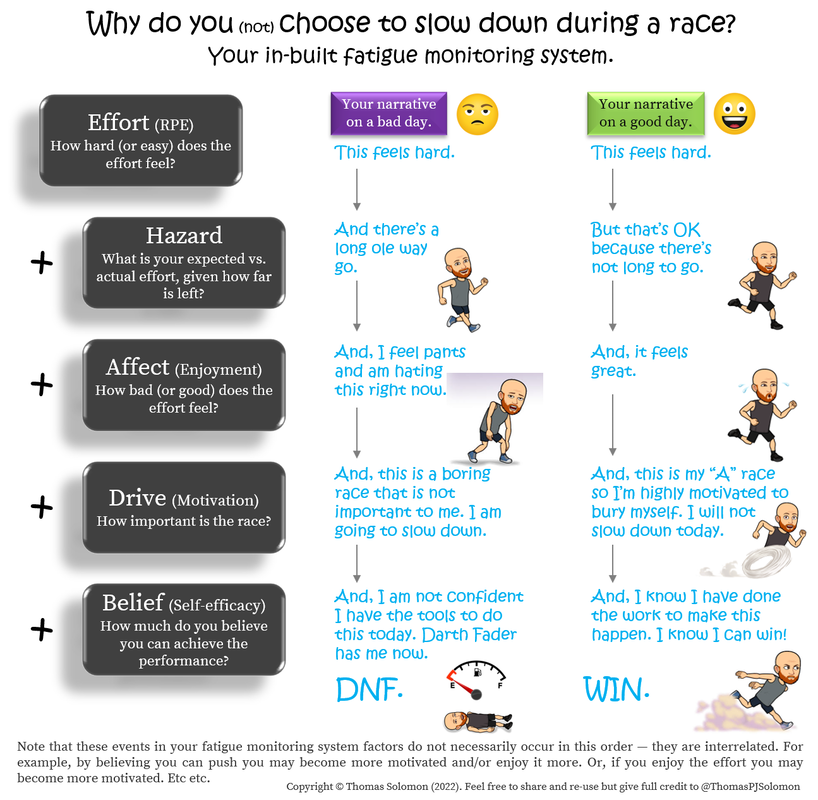

Perceived exertion is essentially your emotive feeling of effort to the physical work of your muscles, heart, lungs, etc — “How hard does the effort feel?”. Your level of perceived exertion (your RPE) is driven by a combination of the external load (pace/speed) and how well conditioned (physically, psychologically, and emotionally) you are to deal with it. If you speed up, you need to activate more muscle fibres so your brain sends a signal to the muscles to make that happen. Similarly, if you are slowing down (due to fatigue), you need to activate more muscle fibres to prevent loss of speed so your brain once again sends a signal. Interestingly, in both contexts, speeding up and not wanting to slow down requires a higher level of effort. But, when considering fatigue, RPE misses some important things…

How does the effort “affect” you?

RPE misses how the effort affects your feelings of enjoyment. This is important because how enjoyable an effort feels can affect your “feelings” of fatigue. An Easy effort run at RPE 4/10 can feel great — low effort, good affect — but it can also feel terrible — low effort, bad affect. Similarly, the effort of a solo 5 km time trial can generate feelings of hatred while the effort of a 5 km race with three-dimensional human competitors around you can be fun.

What is the “hazard” of this current effort?

RPE misses the hazard of your current effort in relation to how long you have left, a mismatch between your expected feeling and your actual feeling of exertion (see here here). For example, you are currently at RPE 9/10 but expected to be at RPE 6-8/10 and still have an hour to go — uh oh. Alternatively, you are at RPE 8/10 but only have 400m to go — you can easily up the effort, don your war face, and unleash the beast.

How “motivated” are you to maintain this current effort?

RPE misses the psychological “drive” required to maintain the effort — i.e. your motivation to continue. For example, a boring session or race that is unimportant to you might make you decide to slow down whereas you might be highly motivated to bury yourself during an “A” race and will not slow down.

Do you “believe” you can maintain this current effort?

RPE also misses “self-efficacy” — the degree to which you “believe” you can keep pushing and achieve your performance goal. If you are not confident you have the tools to unleash today, then Darth Fader may bring you down

×

![]()

To summarise, the reasons you slow down (fatigue) are related to your level of effort (RPE), the hazard of your current effort, your enjoyment of the effort, your motivation to continue, and how much you believe you can maintain the effort. And, all these factors are interrelated — for example, by believing you can push you may become more motivated and/or enjoy it more; or, if you enjoy the effort, you may become more motivated, etc etc. As you can see, it is complicated. To simplify things, consider this… During a race, your RPE tends to increase linearly until it reaches a maximal level, most likely (and hopefully) close to when you dip for the line. But your “maximal tolerable” RPE is a fickle beast and is influenced by circumstance:

You will tolerate more discomfort and enjoy a higher RPE for longer when you are highly motivated and believe you can.

A very simple self-demonstration of this is the Strongman-esque “Thor’s hammer” test. You don't need a pair of Thor’s hammers but go fetch a pair of books (or beers or dumbbells) of equal size, place one in each hand and hold them out to your sides, arms parallel to the ground and palms facing to Asgard. Hold those books for as long as you can. Recognize the stages of fatigue you go through — the level of effort compared to how hard you thought it would be, your sensations of increasing muscular discomfort and pain, your desire to end, and your motivation to continue… Keep holding… This is no different from giving it large in a race and then trying to continue giving it large when things get tough. Physiology, psychology, and emotions in action.

×

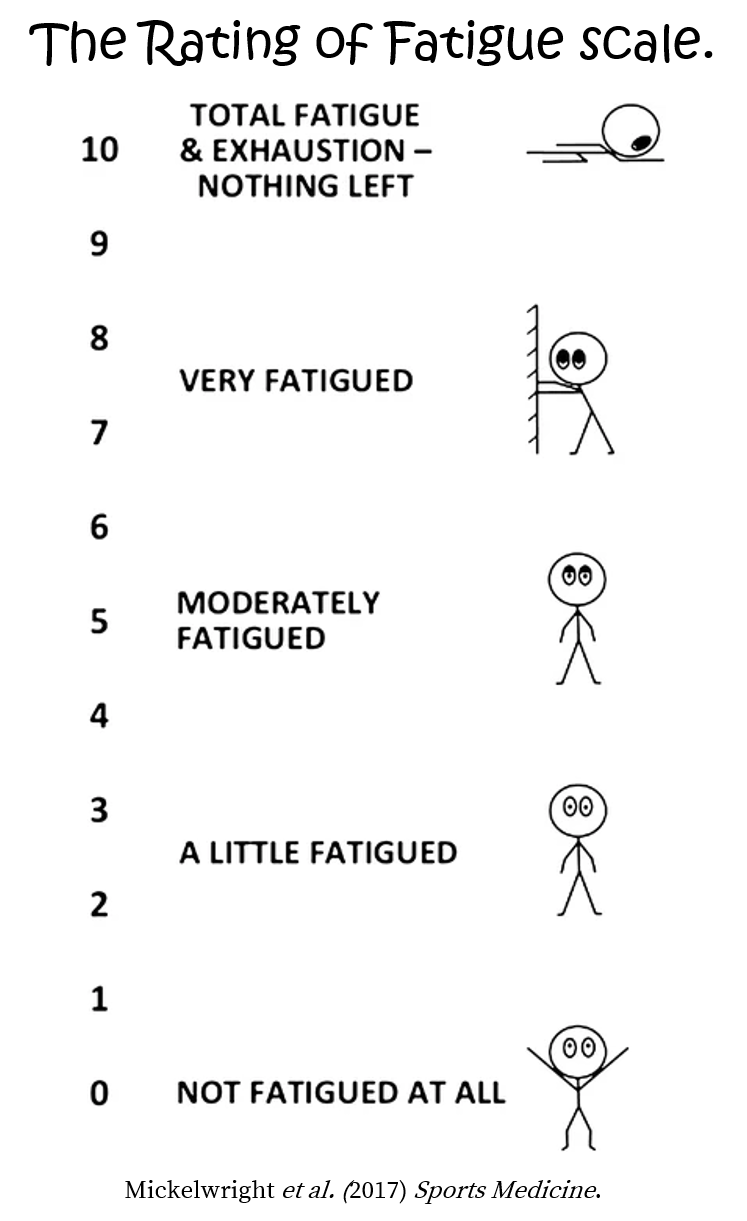

![]()

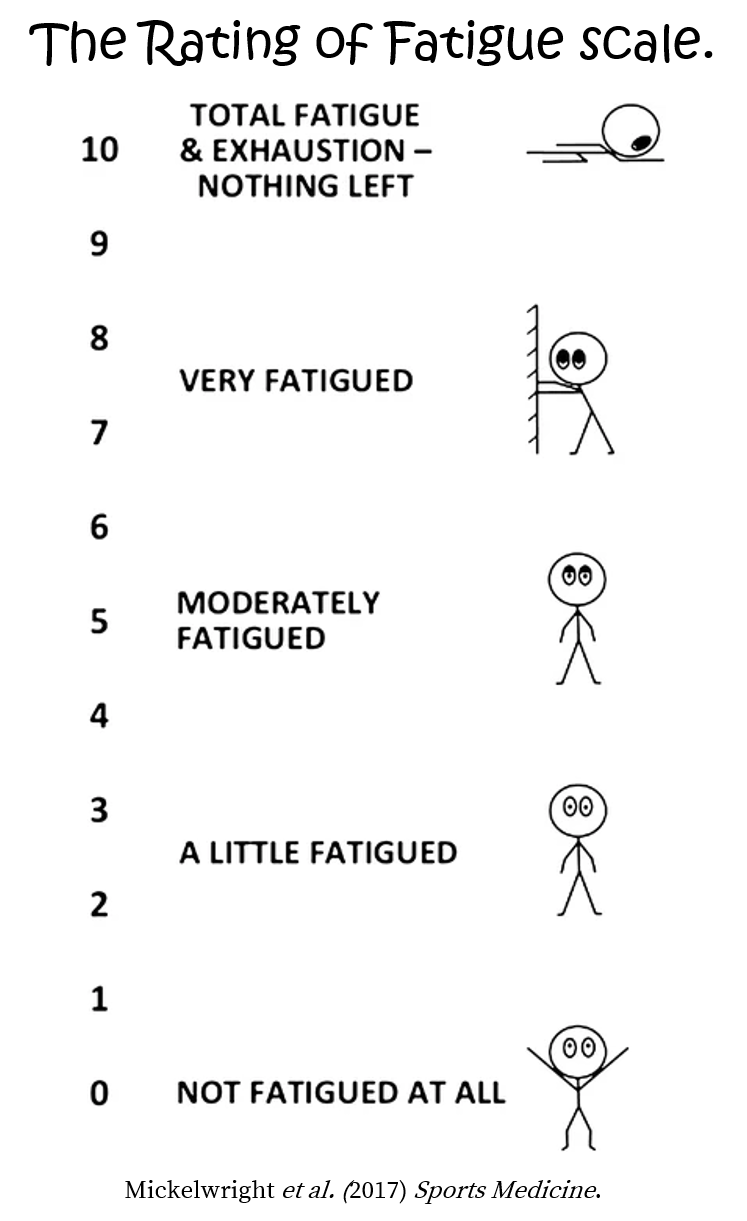

So, you are probably now starting to see that you slow down during exercise because of the level of physical and psychological effort, which combines actual effort, expected effort, enjoyment, motivation, and self-belief. Because perceived fatigue is a personal perceptual phenomenon — only you know how fatigued you feel. Consequently, the simplest way to assess your perceived fatigue during exercise is to use a validated rating-of-fatigue scale — on a scale of zero to 10, how fatigued do you feel? In their validation of such a scale, Dominic Micklewright and colleagues argued that perceived fatigue during exercise is “a feeling of diminishing capacity to cope with physical or mental stressors, either imagined or real”. I rather like that. But, the best thing about all of this, is you don’t need to invest much thought into rating your fatigue when you are giving it large during a race — you don’t need to worry about all the “chicken and egging” between fatigue and effort because your mighty brain does all that in the background, monitoring all the physiological inputs to protect you from perishing. Similarly, you also don’t need to complicate things during a race by trying to rate your psychological or emotional state (affect, hazard, drive, belief, etc).

So, why on Earth did I tell you about all of it?

Because, as you will discover in Part 2 and Part 3, these concepts will eventually form a foundation of your “how to resist fatigue” checklist.

Now you know what fatigue is, it's a good time to discuss the wicked ways fatigue rears its ugly head… So,

How does Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue  , reveal himself during a race?

, reveal himself during a race?

Going deep on race day tests all your physiological, psychological, and emotional attributes and pushes you towards your metabolic, cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular, nutritional, thermoregulatory, psychological, and emotional capacities. If you cannot resist fatigue, you feel more discomfort, you feel less springy, and you slow down as things feel harder. “I have you now, Obi wan.”, Darth Fader would say.

So, how does fatigue present itself on race day?

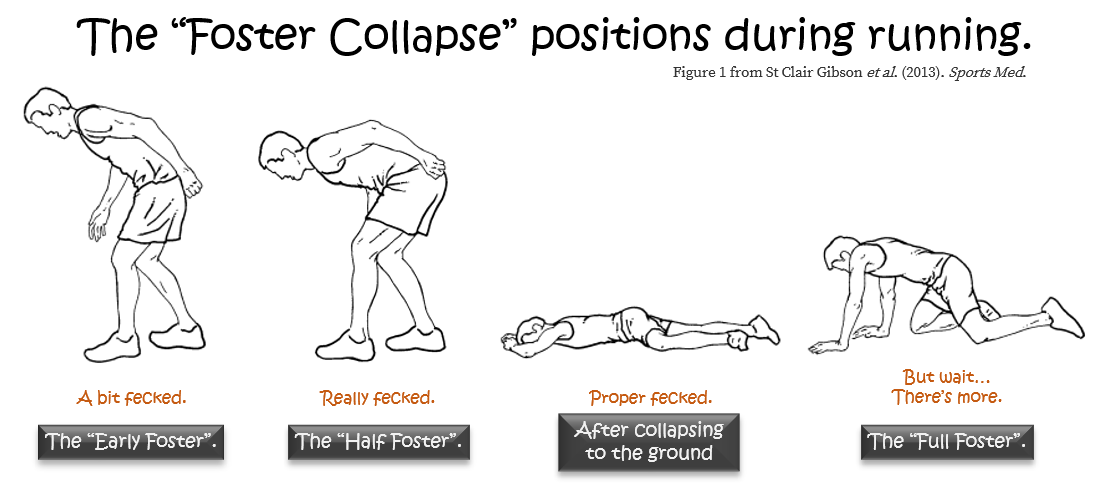

One of the most amusing things in exercise science is a 2013 paper presenting the stages of collapse during fatigue in runners, aka the “Foster collapse”. For me, dramatic collapses are stereotypical of the finish line mayhem in Decathlon/Heptathlon 800m/1500m races, xc-ski races, and Laura Muir at the end of any race she ever does. Anyone who has ever “bonked” on a long run, or failed a set of lifts or pull-ups, or developed so much “arm pump” that you can no longer hang on a wall or swing through an OCR rig, has experienced some kind of “collapse”. If you have not, fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on perspective), some incredible detonations have been captured live during world-class championships events.

There is the classic Sian Welch & Wendy Ingraham “full Foster” crawl to become Iron(wo)man. Gabriela Andersen-Schiess stumbling to marathon completion at the 1984 Olympics in LA. We’ve seen Paula Newby Fraser collapse at Ironman World Champs 2005. In 2016, we saw Jonny Brownlee’s complete detonation when his brother had to carry him to the finish at a World Cup triathlon race. In 2017, we saw Joshua Cheptegai assuredly on his way to gold at the World Cross Country champs in front of his ecstatic home crowd in Uganda, only to completely detonate in the final km. Callum Hawkins lost gold when he collapsed at the 2018 Commonwealth Games marathon in Australia. And, in Tokyo 2020, the Brazilian runner, Daniel Do Nascimento, had multiple collapses until his eventual DNF in the Olympic marathon. World-class athletes are not immune to fatigue; they just move faster and resist fatigue for longer.

×

![]()

These TNT-like detonations send folks from emulating an economical butterfly floating on the wind to impersonating a heavy, sludge-dredging tug boat spluttering like the doom of time. It's like someone filled their shoes with tar and stuck pins in their quads. While all of these examples end in the same thing — slowing down followed by either a DNF or a loss of medals — they occur for different reasons (I will get to that in Part 2 and Part 3) and you can see how heroically they all try to keep going — not all heroes wear capes. But, for now, let’s consider how fatigue might appear to you…

Perhaps you tried to run at Kipchoge pace on a treadmill and slowed down rapidly — this is fatigue. Maybe you’ve experienced a race-day (or during-session) TNT-like detonation — a sudden bonk — or a race-day (or during-session) fade — a gradual deterioration in power output. Perhaps you’ve experienced a kinematic/biomechanical deterioration during closing stages of a race — shortening strides, lessening knee lift, or “pedalling in squares” on a bike. Maybe you’ve experienced muscle cramps. Perhaps you’ve encountered heat stress — “I can’t see, I feel like a furnace, I feel sick, and now I am on the ground”. Or maybe cold stress or hypothermia — “I can’t see, I am shivering, I am making silly decisions, and now I am on the ground”. Or perhaps, you’ve lost motivation to push hard during a race — a brain fade, “I just can’t be bothered to push today”. In all scenarios, it feels like your effort is high but progress is poor — you try to give it large but can only give it medium-small.

Essentially… we slow down during prolonged and/or hard efforts to protect the body from damage and complete failure. For example, prolonged exposure to low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) or high core temperature (hyperthermia) can also irreversibly damage nerves and blood vessels. So, maybe Darth Fader isn’t such a bad dude after all. Perhaps the Sith Lord of Fatigue is actually protecting you from permanent damage. That sounds great but let’s be honest, during a race, your goal is to win, not survive.

To summarise…

As I said at the beginning, this series is not about chronic fatigue or overtraining syndrome or simply feeling tired, it is about failing to maintain power output or speed during exercise. From that perspective, in this series,Fatigue (or slowing down) is related to your level of effort but the level of effort you are willing to make is also related to your feelings of fatigue. When we measure (or attempt to measure) fatigue, it involves a balance of your actual effort, your expected effort, your enjoyment, your motivation, and your self-belief, and as you might by now have realised these things cannot be entirely driven by what is happening in your muscles. If you have come to that conclusion, you are bang on the money and in Part 2 and Part 3 I will go deep on all the various causes of why we slow down when we don’t expect to and least want to — the various causes that invite a visit from the Sith Lord of Fatigue

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I am passionate about equality in access to free education. If you find value in my content, please help keep it alive by sharing it on social media and buying me a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join me @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to my free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out my other Articles, Nerd Alerts, Free Training Tools, and my Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to my articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.