Opinion:

What do you say to a (vapor)fly? … “Shoe”. But supershoes are probably here to stay.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

30th Jan 2021.

Reading time ~20-mins (4000-words).

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

There was a time when a popular running book convinced millions that running barefoot was the path to performance dominance. Occasionally, a Dad would rock up to his kid’s school sports day planning to dominate the dads’ race in his “new shoes” while the other Dads would gaze on in astonishment and shout, “but he isn't wearing anything at all!”...

Those days are long gone and there is a new “Emperor” in town — Eliud Kipchoge — who wore his “new clothes”, the regulation-conforming, 40 mm stack-height, carbon blade-embedded, swoosh-clad shoes, to smash the 2-hour marathon mark. And, he did so with what looked like pain-free ease. Running at 21 KPH should not be easy and it should certainly not be easy to do for 2-hours. That was 2019, when the world was still “normal”, not ordinary, but normal.

What happened next was not normal and it was far from ordinary.

Among the world-class events of 2020, there were several brain-aching efforts:

In January, the year started warming up when Kenya’s Rhonex Kipruto destroyed the men’s 10 km road world record in Valencia — 26:24.

In January, the year started warming up when Kenya’s Rhonex Kipruto destroyed the men’s 10 km road world record in Valencia — 26:24.

In February, Ethiopia’s Ababel Yeshaneh blasted to a new womens’ half-marathon world record in the UAE — 1:04:31.

In February, Ethiopia’s Ababel Yeshaneh blasted to a new womens’ half-marathon world record in the UAE — 1:04:31.

In the same month, Uganda's Joshua Cheptegei smashed the 5 km road world record in Monaco — 12:51.

In the same month, Uganda's Joshua Cheptegei smashed the 5 km road world record in Monaco — 12:51.

Later in the year, in August, on the track in Monaco Cheptegei took the 5000m track world record — 12:35.

Later in the year, in August, on the track in Monaco Cheptegei took the 5000m track world record — 12:35.

In September, Britain’s Mo Farah set a new 1-hour track world record in Brussels — 21,330 m — while Sifan Hassan from The Netherlands followed up an hour later with the womens’ record — 18,930 m.

In September, Britain’s Mo Farah set a new 1-hour track world record in Brussels — 21,330 m — while Sifan Hassan from The Netherlands followed up an hour later with the womens’ record — 18,930 m.

Then, in October, Cheptegei returned to the track to break the 10,000m world record in Valencia — 26:11.

Then, in October, Cheptegei returned to the track to break the 10,000m world record in Valencia — 26:11.

And, just moments later at the same meet, Ethiopia’s Letesenbet Gidey smashed the womens’ 5000m world record — 14:06.

And, just moments later at the same meet, Ethiopia’s Letesenbet Gidey smashed the womens’ 5000m world record — 14:06.

Finally, to add the topper to the tree in December, Kenya’s Kibiwott Kandie annihilated the mens’ half-marathon world record — 57:32 — in Valencia, with the next three folks close behind him also eclipsing the existing record — Uganda’s Jacob Kiplimo (57:37) and Kenyans Rhonex Kipruto (57:49) and Alexander Mutiso (57:59).

Finally, to add the topper to the tree in December, Kenya’s Kibiwott Kandie annihilated the mens’ half-marathon world record — 57:32 — in Valencia, with the next three folks close behind him also eclipsing the existing record — Uganda’s Jacob Kiplimo (57:37) and Kenyans Rhonex Kipruto (57:49) and Alexander Mutiso (57:59).

Plus, we should certainly not forget that at the end of 2019, Kenya's Brigid Kosgei broke the womens’ marathon world record — 2:14:04 — at the Chicago Marathon and Eliud Kichoge ran a ridiculous 1:59:40 exhibition marathon in Vienna.

Plus, we should certainly not forget that at the end of 2019, Kenya's Brigid Kosgei broke the womens’ marathon world record — 2:14:04 — at the Chicago Marathon and Eliud Kichoge ran a ridiculous 1:59:40 exhibition marathon in Vienna.

Phew — I’m breaking my critical speed just thinking about it!

It has indeed been a ridiculous 12(ish)-months. But, while incredible to watch, these events do prompt an important question...

Let’s start with genetics. A riveting topic, but while genetics indeed plays a massive role in performance and adaptations to training, it is highly unlikely that a major genome shift has occurred in the past 12-months.

What about the elephant in the room — doping? In 2020, due to COVID-induced restrictions, fewer out-of-competitions tests were conducted and some anti-doping agencies completely discontinued their testing amidst the lock-downs. But, despite less testing, there were more positive tests in athletics than usual and several high profile bans (Wilson Kipsang, Christian Coleman, Ruth Jebet) have been imposed for doping violations including those three-missed-tests-and-you’re-out departures.

With the COVID-induced break from the norm, it probably has been easier to dope but some folks have also been more able to focus on training and recovery than usual. Additionally, athletes have had no race season to deal with, which means less travel and less training interruption. So a possible explanation for the 12-months of power-ups might be folks’ increased freedom to focus on undistracted training blocks with more time for rest and better quality eats and sleeps. Coupling this with the peace of mind arising from not having to plan logistics, not having to stress over whether training is going well (or not), and not having to stress over beating (or losing to) opponents, may also have allowed more brain peace and calm to further support recovery.

These speculations are fun to ponder but theorising on the recent performance-boosting role of training, recovery, psychology, and doping, while enticing, is not directly supported by evidence. For example, we do not know whether the athletes who have raised the bar in the last 12-months have doped, nor do we know how their lives and training have been affected by COVID, nor do we know whether they have worked-out and/or recovered more optimally than usual.

However, there is one other factor that is a strong candidate for pulling the strings...

In Tokyo, the swoosh-clad Vaporfly dominated with athletes putting down some ridiculous performances: the Japanese National record was smashed, bringing it down to 2:05:29, 28 men broke 2:10, and 10 women went under 2:30.

The US trials were more interesting. Some brands, like ON, allowed their athletes to wear any shoe. Many non sponsored athletes, including the eventual second-placed male, Jake Riley, chose to don swooshed models, which were freely available in the event village. Some athletes even reportedly wore “Transformers” — Nike’s in disguise — to appease their sponsors as athletes have done at other races. In the mens’ race, everyone that wore some derivation of the swoosh-clad Vaporfly or Alphafly dominated the top 10, while the womens’ race was won by a non-swoosh, but still carbon fibre-clad, Hoka shoe and the top 10 included a veritable smorgasbord of carbon-infused brands.

For the other events of 2020 where world records fell like dominos, the epic “feets” of endurance were all achieved with carbon-fibre “super shoes”...

Nike’s Vaporfly NEXT% shoe clung to the feet of Brigid Kosgei and Eliud Kipchoge when they broke the marathon world records, Ababel Yeshaneh when she broke the half-marathon world record, and Joshua Cheptegei when he broke the 5 km road world record. On the track, aided by pacing from the metronome-like “wavelight” technology, Nike’s carbon-fibre Dragonfly spike propelled Joshua Cheptegei’s 5000m and 10,000m world records, Letesenbet Gidey 5000m world record, and Mo Farah’s and Sifan Hassan’s 1-hour records. But Nike were not the only record breakers. Rhonex Kipruto broke the men’s 10 km road world record by floating along in a carbon-fibre Adidas prototype. While at the Valencia half marathon, among Kibiwott Kandie, Jacob Kiplimo, Rhonex Kipruto, and Alexander Mutiso, the four men who dipped under the previous world record, two wore Nike’s Alphafly NEXT% and two wore a prototype of the 5-carbon-rodded Adidas’ Adizero Adios Pro shoes.

A little more insight into how popular these “super shoes” are becoming, was found at the World Half Marathon Champs in October 2020, where a huge number of national records and PBs fell. Of the 117 finishers 50 wore a Vaporfly, 25 donned an Alphafly, and 14 laced up in Adidas' Adizero Adios Pro. Only 8 athletes wore a non-carbon-plated shoe — none of them featured highly in the race — and the remaining athletes wore various carbon-fibre infused shoes from Asics, Saucony, New Balance, and Brooks.

This can be viewed as rather exciting. But there is a tough pill to swallow…

Troop’s feelings were clear — he had to go against his morals to allow Riley to choose his own path. His feelings echo my own. When athletes are racing at the world-class end of the field, I can understand the “levelling the playing field” attitude. But, that is also a dangerous justification because it is the same reason other athletes justify doping. On the other hand, athletes who are further down the field are merely racing themselves in a time trial against the clock. For them, training hard might have gotten them their well-deserved PB but by adding a 40 mm stack-height, carbon blade-embedded, swoosh-clad shoe into the mix, they will never know if “they” are better or if their time was only bettered by technology. Some folks are fine with just running faster, at any cost. I am not. Either way, we should not be having this discussion and would not be having this discussion if World Athletics were protecting the integrity of sport.

The reality is that the discussions are being had and the “next-gen” shoes are now embedded in athletics… So, what is so special about them?

Back in the early 90s, with my long ginger hair and acne, I remember Reebok Graphlites — old school carbon fibre shoes with their bizarre missing wedge under the midfoot. In the early 2000s, Adidas also dabbled in the carbon game. And, let’s definitely not forget that before Oscar Pistorius was locked up behind carbon-containing steel bars, his legs were made of carbon-fibre blades.

My point is that running with carbon fibre is not new. Data shows that inserting carbon fibre plates into a shoe’s midsole to increase longitudinal bending stiffness improves running economy, more greatly so in heavier subjects. We also know that increasing the longitudinal bending stiffness with a thicker carbon plate causes a greater ground reaction force in the lever arms of our lower extremity joints during the push-off phase of running.

Nike was the first brand to go large with carbon and combine it with a low mass, more cushioned shoe, introducing the world to the Vaporfly 4% in 2016. Then, nearly a year later, competing brands followed — Hoka, New Balance, Asics, Brooks, Saucony, and Adidas have since developed their own light-weight, highly cushioned, carbon fibre clogs, but are they lagging behind?

Well, we don’t actually know because there are only published experimental studies on the original Swoosh-clad Vaporfly 4% model. No doubt this will change and I hope it does because, right now, the only comparisons that can be made between the various brands’ carbon-fibre clogs are from anecdotal observations in the field. As the story is unfolding, the Nike Vaporfly/Alphafly NEXT% models dominate the medals and the records, with the Adidas Adizero Adios Pro coming a close second. Sadly, notice how I refer to the race dominance by the shoe not the athlete.

Since fatigue during a long race can alter biomechanics and impair economy, one may speculate that race-day benefits of carbon fibre super shoes are even more pronounced than those found in short-duration lab tests. It is also notable that all lab studies have used level running so we do not yet know the effects of these “super shoes” on incline and decline running, which changes the energy cost of running. That said, manufacturers like Hoka, who released their crazy TenNine downhill shoe, are likely well aware that shoe soles stacks that help offset downhill or uphill grades can minimize oxygen costs. It appears that North Face might also be aware of this, with the recent release of their Flight VECTIV trail shoe.

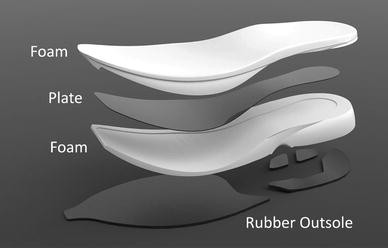

The anatomy of the Nike Vaporfly 4%.

Image Copyright © Hoogkamer et al (2018) Sports Med.

Shared via Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

When examining the type of carbon plate, one study compared four Vaporfly prototypes finding that, when compared to a Vaporfly without a carbon plate, a flat vs. a moderately-curved vs. a highly-curved plate incrementally lowered the energy cost of running. This suggests that when the highly-cushioned ZoomX foam is combined with a highly-curved carbon plate, which is only made possible by a large stack height (e.g. 40 mm), there is a symbiotic 1 + 1 = 3 scenario — you need both components and gain nothing with just one of them.

We also know that the Vaporfly causes less leg soreness and lower levels of muscle damage following a marathon when compared to the Zoom Pegasus and that, during a week of training, the Vaporfly prevents the fatigue-induced decline in pace enabling athletes to maintain training loads for longer. These types of effects combined with improved economy can manifest performance gains — and that is what we are seeing... Athletes are more likely to improve 3 km TT performance in a Vaporfly and a New York Times analysis of 500,000 marathon race entries on Strava data revealed that “Vaporflys ran 3 to 4 percent faster [on average] than similar runners wearing other shoes, and more than 1 percent faster [on average] than the next-fastest racing shoe”.

Given this knowledge, for some reason, only Nike and Adidas have developed shoes pushing right up to the maximum allowable 40 mm stack height. But this does not necessarily mean that the Vaporfly/Alphafly or Adios Pro shoes are the “best” shoe for technologically doping your performance. Think of this: Nike and Adidas have the richest contracts and have had the best runners long before carbon-blades were infused into the foam of your shoes. Also, all of the studies have shown large variability in running economy between subjects — some folks benefit more than others — which is why some smart athletes — Malindi Elmore comes to mind — will conduct their own testing to choose the best shoe for them. Always train smart!

The bottom line is that the use of a large stack height helps elongate the foot and allows for the greatest shoe stiffness when a shoe-length S-shaped curved carbon-fibre blade is surrounded by spongy “spring-like” foam. The result: a dramatic lowering of the energy cost of running.

When Speedo released their LZR suit, FINA clamped down after the frequency of new swimming world records became too many hertz for the brain to handle. Amidst the pandemic of running world records, what has World Athletics done about it...? Well...

A year on, we know the answer. They could not. In fact, they have not even tried.

On 28th July 2020, World Athletics once again amended their rule book to raise the allowed stack height of track spikes to 20 mm for track events up to 800m and up to 25 mm for track events 800m or longer — a confusing split but coincidentally in-keeping with the swoosh’s new Dragonfly spike aimed at middle to long-distance track events. In this amendment, meanwhile, the max stack-height allowance for road shoes remained at 40 mm.

In the same rule amendment, in an attempt to level the playing field, World Athletics also announced that they would create an “Athletic Shoe Availability Scheme” to help make all brands’ shoes available to non-sponsored athletes. This was a useful modification of their original “must be available to all” rule, which was ambiguous and theoretically allowed for small batches of custom “prototype” shoes to be released in a running store for a single day to tick the “available to all” box. The technical rules amendment, C2.1, which can be downloaded here, also stated that “one-off shoes made to order (i.e. that are only ones of their kind) to suit the characteristics of an athlete's foot or other requirements are not permitted.” and that such types of one-off shoes would need to be submitted to World Athletics for review and approval prior to competition.

So, since the middle of 2020, it has been clear that:

Shoes with a stack up to 40 mm are allowed on the road but not on the track.

Shoes with a stack up to 40 mm are allowed on the road but not on the track.

Distance racing spikes are allowed a stack height of up to 25 mm but sprint racing spikes are only allowed 20 mm.

Distance racing spikes are allowed a stack height of up to 25 mm but sprint racing spikes are only allowed 20 mm.

All shoes must be made available to all via the “Athletic Shoe Availability Scheme” .

All shoes must be made available to all via the “Athletic Shoe Availability Scheme” .

And,

One-off shoes (aka prototypes) are not allowed unless submitted to World Athletics for approval at least 4-months prior to competition.

One-off shoes (aka prototypes) are not allowed unless submitted to World Athletics for approval at least 4-months prior to competition.

By the beard of Zeus. A tricky set of rules for World Athletics to control and ones that did not simplify the existing rule book. But surely their Working Group on Athletic Shoes have it under control. Right…?

Since prototypes were not allowed unless submitted to World Athletics for approval at least 4-months prior to competition, it was very surprising to see that in October 2020, Sara Hall was allowed to by-pass these rules to wear a non-available Asics prototype shoe at the London Marathon. This is not a dig at Hall who had an incredible race and an incredible season, eventually going on to run 2:20:32 at The Marathon Project in December 2020, but simply an example of World Athletics not upholding their end of the bargain.

But it must have triggered something because on the 4th December 2020, within days of Kibiwott Kandie, Jacob Kiplimo, Rhonex Kipruto, and Alexander Mutiso all obliterating the preexisting half-marathon world record in various Nike and Adidas clogs, World Athletes released another update to their rule book in which they changed the rules for Development shoes:

Brands still need to submit development shoes (aka “prototypes”) to World Athletics for evaluation and athletes will need to notify at which races they will use them but athletes are not allowed to use development shoes at World Championship events or the Olympics. This sounds good but development shoes are exempt from the Athlete Availability Scheme and they are permitted at big city marathons and road races, which is where pro-athletes make their coin. So, if you don’t have a shoe sponsor, you lose. Or, if your shoe sponsor doesn’t develop supershoes, you also lose.

Since the World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA) states that “Doping is defined as the occurrence of one or more of the anti-doping rule violations” , then I feel confident in saying that the use of these super shoes is technological doping. It also appears that the rules will continue to permit technological doping.

Essentially, these decisions are made in liaison with World Athletics’ newly-formed Working Group on Athletic Shoes, which includes stakeholders with a balance of knowledge on the topic but it includes 6 shoe brand representatives and only one athlete representative. Sadly, whatever opaque discussions go on behind closed doors, it seems clear to me that World Athletics love over-complicating their rules and clearly do not seem to understand what “protecting the integrity of sport” means. As a result, I have no idea what they are doing as it appears that they do not know what they are doing...

Like the Iron curtain doping era of the 70s/80s where world records were deemed “suspicious”, now with the advent of performance-enhancing super shoes we cannot compare the new with the old — is Cheptegai quicker than Gebrselassie or Gidey better than Radcliffe? We will never know. But, perhaps it is no different to being unable to compare Bannister’s cinder-track sub-4-minute mile (on cinder) to the post-Tartan track era of the mid to late 1960s and El Guerrouj’s current 3:43 mile world record — cinder vs. Tartan is not a fair comparison.

Right, rant over. Calm down Solomon; the sun is setting.

Can someone at FINA who was involved in overruling the LZR swimsuit epic of the 2000s please reach out to World Athletics to help educate them in simplicity (and, perhaps, integrity)?

Can someone at FINA who was involved in overruling the LZR swimsuit epic of the 2000s please reach out to World Athletics to help educate them in simplicity (and, perhaps, integrity)?

Or, if that fails,

Can someone at UCI who was involved in establishing cycling’s “athlete’s hour” (the noble, but now defunct, attempt to unify the 1-hour time trial with “old school” tech to allow riders of all eras to be compared) please reach out to World Athletics to help them develop something similar? (Noting of course that the UCI is not at all well-placed to educate anyone in integrity.)

Can someone at UCI who was involved in establishing cycling’s “athlete’s hour” (the noble, but now defunct, attempt to unify the 1-hour time trial with “old school” tech to allow riders of all eras to be compared) please reach out to World Athletics to help them develop something similar? (Noting of course that the UCI is not at all well-placed to educate anyone in integrity.)

Something is needed because Nike has now published work on an ankle exoskeleton that reduces the oxygen cost of running by ~15% compared to normal shoes — the study authors estimate this to be a 10% increase in running speed with no additional energy cost. Great Odin’s raven — that is immense! That would turn Kipchoge’s marathon pace (2:50 min/km) into a blurry-to-the-eye 2:33 min/km. This would be technological doping on steroids. We must not allow ankle exoskeletons to ever start wrapping themselves around Kipchoge’s talocrural joint. If I could write to Nike, it would read something like this:

What do I say to a fly?

… Shoe.

Well, that is all… Thanks for joining me to hear my viewpoint. Until next time, keep thinking outside the box and keep training smart.

Those days are long gone and there is a new “Emperor” in town — Eliud Kipchoge — who wore his “new clothes”, the regulation-conforming, 40 mm stack-height, carbon blade-embedded, swoosh-clad shoes, to smash the 2-hour marathon mark. And, he did so with what looked like pain-free ease. Running at 21 KPH should not be easy and it should certainly not be easy to do for 2-hours. That was 2019, when the world was still “normal”, not ordinary, but normal.

What happened next was not normal and it was far from ordinary.

2020 turned out to be quite a year!

In 2020, the world became infected with a novel coronavirus and the running world became infected with a mix of virtual TTs (aka time trials), FKTs (aka fastest known times), a smattering of Diamond League “exhibition” events, and just a few “real” races, like the World Half Marathon champs and the Valencia marathon. Personally, I was fortunate to take part in two virtual mountain race series in my hometown. But, with the exception of one of our esteemed locals romping up the vertical kilometre route in 38-minutes, these were far from world-class.Among the world-class events of 2020, there were several brain-aching efforts:

It has indeed been a ridiculous 12(ish)-months. But, while incredible to watch, these events do prompt an important question...

Why have there been so many epic performances in such a short period?

We could just argue that it is simply time for a breakthrough. But we are smarter than that and have knowledge of possible reasons.Let’s start with genetics. A riveting topic, but while genetics indeed plays a massive role in performance and adaptations to training, it is highly unlikely that a major genome shift has occurred in the past 12-months.

What about the elephant in the room — doping? In 2020, due to COVID-induced restrictions, fewer out-of-competitions tests were conducted and some anti-doping agencies completely discontinued their testing amidst the lock-downs. But, despite less testing, there were more positive tests in athletics than usual and several high profile bans (Wilson Kipsang, Christian Coleman, Ruth Jebet) have been imposed for doping violations including those three-missed-tests-and-you’re-out departures.

With the COVID-induced break from the norm, it probably has been easier to dope but some folks have also been more able to focus on training and recovery than usual. Additionally, athletes have had no race season to deal with, which means less travel and less training interruption. So a possible explanation for the 12-months of power-ups might be folks’ increased freedom to focus on undistracted training blocks with more time for rest and better quality eats and sleeps. Coupling this with the peace of mind arising from not having to plan logistics, not having to stress over whether training is going well (or not), and not having to stress over beating (or losing to) opponents, may also have allowed more brain peace and calm to further support recovery.

These speculations are fun to ponder but theorising on the recent performance-boosting role of training, recovery, psychology, and doping, while enticing, is not directly supported by evidence. For example, we do not know whether the athletes who have raised the bar in the last 12-months have doped, nor do we know how their lives and training have been affected by COVID, nor do we know whether they have worked-out and/or recovered more optimally than usual.

However, there is one other factor that is a strong candidate for pulling the strings...

Technological “doping”.

At the US Marathon trials in February 2020 and the Tokyo marathon in March 2020, two of the few real races of the year, it was a show-down between the 40 mm stack-height, carbon blade-embedded, swoosh-clad shoes and whatever the non-swoosh-sponsored rivals could clad their feet in.In Tokyo, the swoosh-clad Vaporfly dominated with athletes putting down some ridiculous performances: the Japanese National record was smashed, bringing it down to 2:05:29, 28 men broke 2:10, and 10 women went under 2:30.

The US trials were more interesting. Some brands, like ON, allowed their athletes to wear any shoe. Many non sponsored athletes, including the eventual second-placed male, Jake Riley, chose to don swooshed models, which were freely available in the event village. Some athletes even reportedly wore “Transformers” — Nike’s in disguise — to appease their sponsors as athletes have done at other races. In the mens’ race, everyone that wore some derivation of the swoosh-clad Vaporfly or Alphafly dominated the top 10, while the womens’ race was won by a non-swoosh, but still carbon fibre-clad, Hoka shoe and the top 10 included a veritable smorgasbord of carbon-infused brands.

For the other events of 2020 where world records fell like dominos, the epic “feets” of endurance were all achieved with carbon-fibre “super shoes”...

Nike’s Vaporfly NEXT% shoe clung to the feet of Brigid Kosgei and Eliud Kipchoge when they broke the marathon world records, Ababel Yeshaneh when she broke the half-marathon world record, and Joshua Cheptegei when he broke the 5 km road world record. On the track, aided by pacing from the metronome-like “wavelight” technology, Nike’s carbon-fibre Dragonfly spike propelled Joshua Cheptegei’s 5000m and 10,000m world records, Letesenbet Gidey 5000m world record, and Mo Farah’s and Sifan Hassan’s 1-hour records. But Nike were not the only record breakers. Rhonex Kipruto broke the men’s 10 km road world record by floating along in a carbon-fibre Adidas prototype. While at the Valencia half marathon, among Kibiwott Kandie, Jacob Kiplimo, Rhonex Kipruto, and Alexander Mutiso, the four men who dipped under the previous world record, two wore Nike’s Alphafly NEXT% and two wore a prototype of the 5-carbon-rodded Adidas’ Adizero Adios Pro shoes.

A little more insight into how popular these “super shoes” are becoming, was found at the World Half Marathon Champs in October 2020, where a huge number of national records and PBs fell. Of the 117 finishers 50 wore a Vaporfly, 25 donned an Alphafly, and 14 laced up in Adidas' Adizero Adios Pro. Only 8 athletes wore a non-carbon-plated shoe — none of them featured highly in the race — and the remaining athletes wore various carbon-fibre infused shoes from Asics, Saucony, New Balance, and Brooks.

This can be viewed as rather exciting. But there is a tough pill to swallow…

The moral dilemma.

In October 2020, Olympic marathon legend-turned-coach, Lee Troop was interviewed on the Clean Sport Collective Podcast. Among the many interesting topics, he viewed his opinion on the Swoosh shoe debate, which was heartfelt because his own then unsponsored athlete, Jake Riley, wore a free pair of Vaporflys for the US Olympic marathon trials. Riley finished 2nd that day, earning his spot in Tokyo. But the coach-athlete dynamic was a tricky one: wear a shoe from a brand you do not like, plus wear a shoe you know will enhance your performance, or choose not to wear such a shoe thus metaphorically giving your competitors a head start.Troop’s feelings were clear — he had to go against his morals to allow Riley to choose his own path. His feelings echo my own. When athletes are racing at the world-class end of the field, I can understand the “levelling the playing field” attitude. But, that is also a dangerous justification because it is the same reason other athletes justify doping. On the other hand, athletes who are further down the field are merely racing themselves in a time trial against the clock. For them, training hard might have gotten them their well-deserved PB but by adding a 40 mm stack-height, carbon blade-embedded, swoosh-clad shoe into the mix, they will never know if “they” are better or if their time was only bettered by technology. Some folks are fine with just running faster, at any cost. I am not. Either way, we should not be having this discussion and would not be having this discussion if World Athletics were protecting the integrity of sport.

The reality is that the discussions are being had and the “next-gen” shoes are now embedded in athletics… So, what is so special about them?

The science of a shoe.

Several shoe advances have been made over the years — spikes, cushioning, lighter foams, etc. A systematic review of the literature found that running economy is most improved by a shoe with a lower mass, more cushioning, and a greater longitudinal shoe stiffness, while greater shoe mass impairs running time trial performance.Back in the early 90s, with my long ginger hair and acne, I remember Reebok Graphlites — old school carbon fibre shoes with their bizarre missing wedge under the midfoot. In the early 2000s, Adidas also dabbled in the carbon game. And, let’s definitely not forget that before Oscar Pistorius was locked up behind carbon-containing steel bars, his legs were made of carbon-fibre blades.

My point is that running with carbon fibre is not new. Data shows that inserting carbon fibre plates into a shoe’s midsole to increase longitudinal bending stiffness improves running economy, more greatly so in heavier subjects. We also know that increasing the longitudinal bending stiffness with a thicker carbon plate causes a greater ground reaction force in the lever arms of our lower extremity joints during the push-off phase of running.

Nike was the first brand to go large with carbon and combine it with a low mass, more cushioned shoe, introducing the world to the Vaporfly 4% in 2016. Then, nearly a year later, competing brands followed — Hoka, New Balance, Asics, Brooks, Saucony, and Adidas have since developed their own light-weight, highly cushioned, carbon fibre clogs, but are they lagging behind?

Well, we don’t actually know because there are only published experimental studies on the original Swoosh-clad Vaporfly 4% model. No doubt this will change and I hope it does because, right now, the only comparisons that can be made between the various brands’ carbon-fibre clogs are from anecdotal observations in the field. As the story is unfolding, the Nike Vaporfly/Alphafly NEXT% models dominate the medals and the records, with the Adidas Adizero Adios Pro coming a close second. Sadly, notice how I refer to the race dominance by the shoe not the athlete.

So, what do we know about the science of the Vaporfly 4%?

The experimental data collected to date has been on treadmills during short 3- to 5-minute bouts to measure the oxygen cost (running economy) at various sub-maximal speeds. As yet, only one lab study has examined running time trial performance. However, we do have the real-world race-day data that I just described to act as a surrogate for the lack of time trial performance lab data.Since fatigue during a long race can alter biomechanics and impair economy, one may speculate that race-day benefits of carbon fibre super shoes are even more pronounced than those found in short-duration lab tests. It is also notable that all lab studies have used level running so we do not yet know the effects of these “super shoes” on incline and decline running, which changes the energy cost of running. That said, manufacturers like Hoka, who released their crazy TenNine downhill shoe, are likely well aware that shoe soles stacks that help offset downhill or uphill grades can minimize oxygen costs. It appears that North Face might also be aware of this, with the recent release of their Flight VECTIV trail shoe.

Image Copyright © Hoogkamer et al (2018) Sports Med.

Shared via Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

×

![]()

Experimental studies have clearly shown that when compared to other non-carbon-plated marathon racing shoes or spikes the Vaporfly 4% reduces the oxygen cost of running in trained runners, even when the mass of the different brands’ shoes are matched. This effect is associated with the greater energy storage in the midsole foam, a “lever effect” of the carbon-fibre plate on the ankle joint, plus a stiffening effect of the carbon-fibre plate on the metatarsophalangeal joints in the toes. Other studies have found that the Vaporfly 4% increases stride length and plantarflexion velocity and that improved economy is also associated with lower ground contact times.

When examining the type of carbon plate, one study compared four Vaporfly prototypes finding that, when compared to a Vaporfly without a carbon plate, a flat vs. a moderately-curved vs. a highly-curved plate incrementally lowered the energy cost of running. This suggests that when the highly-cushioned ZoomX foam is combined with a highly-curved carbon plate, which is only made possible by a large stack height (e.g. 40 mm), there is a symbiotic 1 + 1 = 3 scenario — you need both components and gain nothing with just one of them.

We also know that the Vaporfly causes less leg soreness and lower levels of muscle damage following a marathon when compared to the Zoom Pegasus and that, during a week of training, the Vaporfly prevents the fatigue-induced decline in pace enabling athletes to maintain training loads for longer. These types of effects combined with improved economy can manifest performance gains — and that is what we are seeing... Athletes are more likely to improve 3 km TT performance in a Vaporfly and a New York Times analysis of 500,000 marathon race entries on Strava data revealed that “Vaporflys ran 3 to 4 percent faster [on average] than similar runners wearing other shoes, and more than 1 percent faster [on average] than the next-fastest racing shoe”.

Given this knowledge, for some reason, only Nike and Adidas have developed shoes pushing right up to the maximum allowable 40 mm stack height. But this does not necessarily mean that the Vaporfly/Alphafly or Adios Pro shoes are the “best” shoe for technologically doping your performance. Think of this: Nike and Adidas have the richest contracts and have had the best runners long before carbon-blades were infused into the foam of your shoes. Also, all of the studies have shown large variability in running economy between subjects — some folks benefit more than others — which is why some smart athletes — Malindi Elmore comes to mind — will conduct their own testing to choose the best shoe for them. Always train smart!

The bottom line is that the use of a large stack height helps elongate the foot and allows for the greatest shoe stiffness when a shoe-length S-shaped curved carbon-fibre blade is surrounded by spongy “spring-like” foam. The result: a dramatic lowering of the energy cost of running.

When Speedo released their LZR suit, FINA clamped down after the frequency of new swimming world records became too many hertz for the brain to handle. Amidst the pandemic of running world records, what has World Athletics done about it...? Well...

World Athletics, what are you doing?

About a year ago, in February 2020, I wrote an article titled “World Athletics + rule change = confusion + sadness”, in which I outlined the January 2020 rule change that World Athletics implemented in response to the development and release of high stack-height, carbon fibre-laden, swoosh-clad shoes. I also discussed how the new ruling would create a problem — specifically, how could World Athletics monitor legal stack heights and legal usage of carbon fibre prior to every race?A year on, we know the answer. They could not. In fact, they have not even tried.

On 28th July 2020, World Athletics once again amended their rule book to raise the allowed stack height of track spikes to 20 mm for track events up to 800m and up to 25 mm for track events 800m or longer — a confusing split but coincidentally in-keeping with the swoosh’s new Dragonfly spike aimed at middle to long-distance track events. In this amendment, meanwhile, the max stack-height allowance for road shoes remained at 40 mm.

In the same rule amendment, in an attempt to level the playing field, World Athletics also announced that they would create an “Athletic Shoe Availability Scheme” to help make all brands’ shoes available to non-sponsored athletes. This was a useful modification of their original “must be available to all” rule, which was ambiguous and theoretically allowed for small batches of custom “prototype” shoes to be released in a running store for a single day to tick the “available to all” box. The technical rules amendment, C2.1, which can be downloaded here, also stated that “one-off shoes made to order (i.e. that are only ones of their kind) to suit the characteristics of an athlete's foot or other requirements are not permitted.” and that such types of one-off shoes would need to be submitted to World Athletics for review and approval prior to competition.

So, since the middle of 2020, it has been clear that:

And,

Since prototypes were not allowed unless submitted to World Athletics for approval at least 4-months prior to competition, it was very surprising to see that in October 2020, Sara Hall was allowed to by-pass these rules to wear a non-available Asics prototype shoe at the London Marathon. This is not a dig at Hall who had an incredible race and an incredible season, eventually going on to run 2:20:32 at The Marathon Project in December 2020, but simply an example of World Athletics not upholding their end of the bargain.

But it must have triggered something because on the 4th December 2020, within days of Kibiwott Kandie, Jacob Kiplimo, Rhonex Kipruto, and Alexander Mutiso all obliterating the preexisting half-marathon world record in various Nike and Adidas clogs, World Athletes released another update to their rule book in which they changed the rules for Development shoes:

C2.1 - Technical Rules, amendment to Rule 5 (download here).

— “Development shoe means a road, cross-country or track or field shoe which has never been Available for Purchase but which a sports manufacturer is developing to bring to market and would like to conduct tests with their sponsored athletes”.

— “Development Shoes are not permitted to be worn at the World Athletics Series or the Olympic Games”.

— “Development Shoes are not required to be made Available for Purchase or subject to the Availability Scheme”.

So, the update adds a complication.

— “Development shoe means a road, cross-country or track or field shoe which has never been Available for Purchase but which a sports manufacturer is developing to bring to market and would like to conduct tests with their sponsored athletes”.

— “Development Shoes are not permitted to be worn at the World Athletics Series or the Olympic Games”.

— “Development Shoes are not required to be made Available for Purchase or subject to the Availability Scheme”.

Brands still need to submit development shoes (aka “prototypes”) to World Athletics for evaluation and athletes will need to notify at which races they will use them but athletes are not allowed to use development shoes at World Championship events or the Olympics. This sounds good but development shoes are exempt from the Athlete Availability Scheme and they are permitted at big city marathons and road races, which is where pro-athletes make their coin. So, if you don’t have a shoe sponsor, you lose. Or, if your shoe sponsor doesn’t develop supershoes, you also lose.

Since the World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA) states that “Doping is defined as the occurrence of one or more of the anti-doping rule violations” , then I feel confident in saying that the use of these super shoes is technological doping. It also appears that the rules will continue to permit technological doping.

Essentially, these decisions are made in liaison with World Athletics’ newly-formed Working Group on Athletic Shoes, which includes stakeholders with a balance of knowledge on the topic but it includes 6 shoe brand representatives and only one athlete representative. Sadly, whatever opaque discussions go on behind closed doors, it seems clear to me that World Athletics love over-complicating their rules and clearly do not seem to understand what “protecting the integrity of sport” means. As a result, I have no idea what they are doing as it appears that they do not know what they are doing...

Like the Iron curtain doping era of the 70s/80s where world records were deemed “suspicious”, now with the advent of performance-enhancing super shoes we cannot compare the new with the old — is Cheptegai quicker than Gebrselassie or Gidey better than Radcliffe? We will never know. But, perhaps it is no different to being unable to compare Bannister’s cinder-track sub-4-minute mile (on cinder) to the post-Tartan track era of the mid to late 1960s and El Guerrouj’s current 3:43 mile world record — cinder vs. Tartan is not a fair comparison.

Right, rant over. Calm down Solomon; the sun is setting.

A suggestion for moving forward...

I don’t hate tech. Tech is exciting. But, as I have said before, I don’t watch sport to see how technology improves human endeavour and I certainly don’t watch sport to cheer on a shoe. Nonetheless, I will have to get used to it since “the race of the branded feet” is very likely here to stay… In the meantime, I can only wish for one of two things:Or, if that fails,

Dear Phil,

I hope your swoosh is in the right place. Robotics have a place in the world for rehab from injury and illness and for helping disabled folks improve their quality of life. In these cases, reducing the energy cost of movement is a welcome treat. But, please don't mess with the beauty of running!

But, when I see Swoosh ticks co-authoring and funding work examining ankle robots, my immediate thought goes to the World Athletics and what they will next ignore and allow to be fitted into a shoe.

I hope your swoosh is in the right place. Robotics have a place in the world for rehab from injury and illness and for helping disabled folks improve their quality of life. In these cases, reducing the energy cost of movement is a welcome treat. But, please don't mess with the beauty of running!

What do I say to a fly?

… Shoe.

Well, that is all… Thanks for joining me to hear my viewpoint. Until next time, keep thinking outside the box and keep training smart.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.