This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — What heat does to you.

→ Part 2 — How to stay cool on race day.

→ Part 3 — How to heat acclimate before race day.

Also check out my related series on:

Training & racing in the cold.

→ Part 1 — What heat does to you.

→ Part 2 — How to stay cool on race day.

→ Part 3 — How to heat acclimate before race day.

Also check out my related series on:

Training & racing in the cold.

Training and racing in the heat. Part 3 of 3:

Beat the heat — how can you use heat acclimation before race day?

Thomas Solomon PhD.

16th Oct 2021.

In Part 1, you learned what heat does to your physiology and performance and why it is important to “keep your cool”. In Part 2, you learned how to “keep your cool” during your sessions and races. Here in Part 3, I will put the rapidly melting icing on your cake and share with you a powerful tool to arm yourself with on race day — heat acclimation.

Reading time ~18-mins.

or listen to “audiobook” Podcast version here.

or listen to “audiobook” Podcast version here.

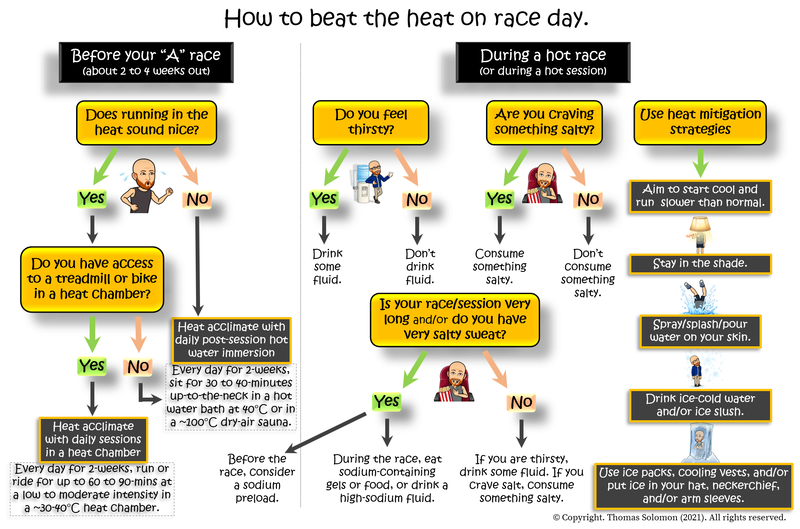

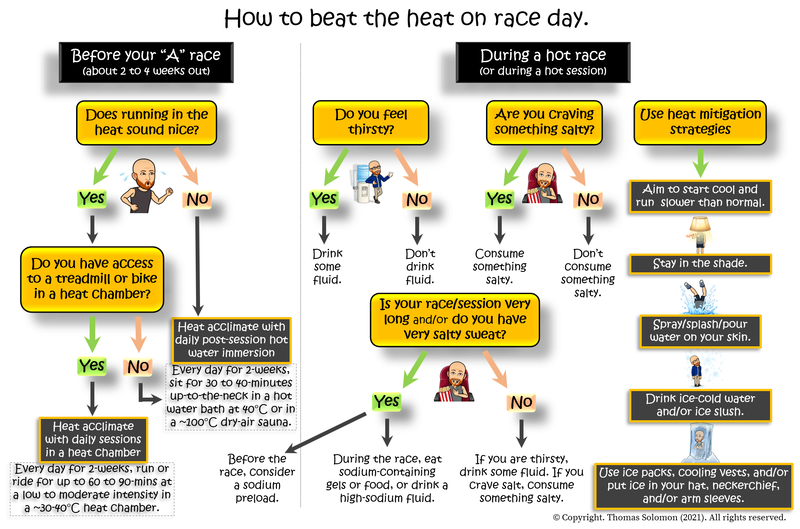

On this step-by-step journey with John Travolta on how you can “Be cool”, you know that lowering your cardiovascular strain (heart rate) and perception of effort (RPE) while boosting your thermal comfort is key for helping you resist fatigue during exercise in the heat. In Part 2, you learned about the heat mitigation strategies you can use during your sessions and races to stay cool but there are also things you can do before race day to adapt to the heat.

The first thing you might not have guessed is that...

That your normal training improves your tolerance to an increasing core temperature during exercise is great but that is not what you came here to hear about… Surely, there is something more you can do?

IMPORTANT: If you are pregnant and/or have any medical conditions, you should consult your doctor before exercising in hot conditions and/or considering using a heat acclimation strategy.

Adapting to the heat does not involve making yourself as dehydrated as possible then running as hard as possible for as long as possible in the hottest air temperature as possible. Being dehydrated and “running hot” for long periods is dangerous (see here & here) and can contribute to acute kidney injury. So, how can you adapt to the heat? Should you exercise in a sauna, sit in a hot pool, eat a Vindaloo, get an infection and ride a fever? All these things make you “feel” hot and increase your cardiovascular strain and sweat rate but only some of them are useful for beating the heat during your next race…

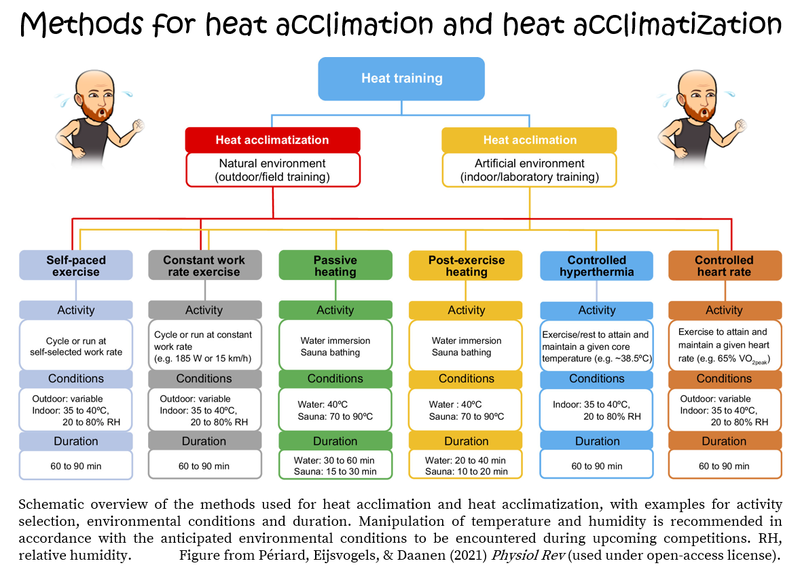

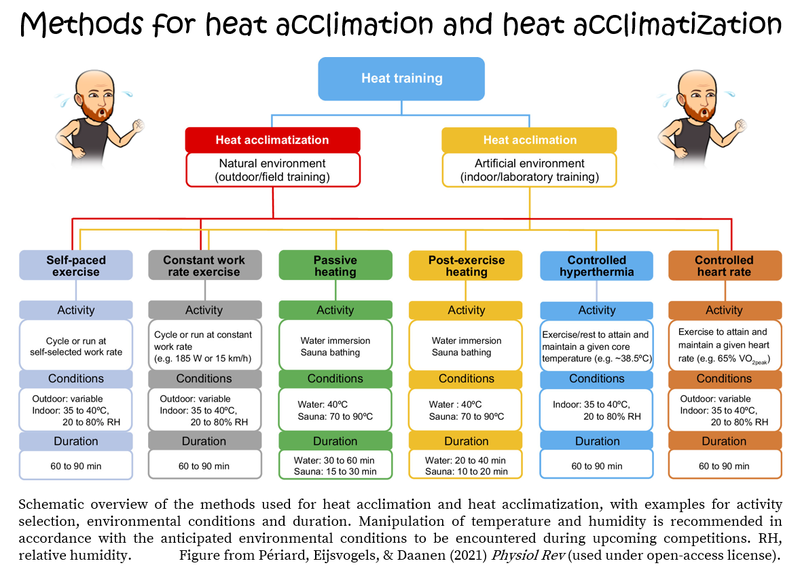

Heat “acclimatization” is what happens when you train outdoors in hot weather, i.e. it is “natural”. Heat “acclimation” is what happens when you adapt following repeated exposure to an artificially hot environment (a hot tub, a sauna, a hot bath, etc). Either way, similar adaptations result… Increased plasma volume (due to increased kidney retention of sodium and better reabsorption of solutes in skin duct cells back into the blood), decreased resting heart rate, less cardiovascular strain during exercise, lower RPE, increased sweat rate at a lower core temperature and, therefore, you start sweating sooner during exercise (fully reviewed in Périard, Eijsvogels, & Daanen in Physiol Rev.).

So,

How can you “acclimatize” to the heat?

How can you “acclimatize” to the heat?

If you live and train in a hot place, you will naturally acclimatize to the hot conditions each summer. This elicits many adaptations and is likely to improve your performance in the heat (see here for a thorough review). If you do not live in a hot place but your “A” race will be in hot conditions, you could choose to “acclimatize” by living and training in the race location for some weeks leading into the event. But, this is not practical for many athletes. Plus, as I will describe below, on its own, acclimatization is likely insufficient for full heat adaptation. Therefore, a simple and highly effective alternative is to heat “acclimate” prior to your race…

How can you “acclimate” to the heat?

How can you “acclimate” to the heat?

Your first option is to sweat in a heat chamber or sauna during your sessions — aka “active” heat acclimation. This is logistically challenging and, as I and many others can attest, is horrible. Plus, because you have to slow down in the heat, your absolute workload is lower and you might come out of a heat-training block slower than you went in. Your second option is to sweat in a sauna, hot tub, or warm bath after your sessions — aka “passive” heat acclimation. Not only is this far less horrible! but you can also train at a normal workload throughout the training block and not worry about any loss of speed. The overall goal of either “heat during” or “heat after” acclimation strategies is simple: raise your core temperature for a prolonged period.

Copyright © Périard, Eijsvogels, & Daanen (2021) Physiol Rev.. Open access licensed under Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY 4.0.

Will adapting to the heat improve your performance?

Will adapting to the heat improve your performance?

First up, doing daily sessions (e.g. running 80-mins/day) in a heat chamber — yuk — has been shown to further benefit runners who are already acclimatized to living and training in hot and humid summer climates. I.e., natural heat acclimatization (i.e. living & training in the heat) may be insufficient for maximal heat adaptation.

Secondly, since training camps are commonly held in hot places, it is important to know that thermoregulatory and performance adaptations following short-term heat acclimation training blocks are rapid. But, not only will you rapidly acquire the adaptations, thermoregulatory and performance benefits are retained for up to 2 to 4-weeks following heat acclimation. For example, Zurawlew et al. (2019) found that 5-days of daily 40-min running at 65%V̇O2max in ~20°C followed by hot water immersion (40 -mins up-to-the-neck in 40 °C water) improved thermoregulatory adaptations during running in the heat (40°C) that persisted for at least 2-weeks (reduced resting and end-exercise core temperature, faster sweating onset, & lower skin temp, heart rate, RPE, and thermal sensation). Meanwhile, Gerrett and colleagues (2021) found improved thermoregulation and performance after 10-days of daily cycling-in-the-heat (35-mins in 33°C) and that thermoregulatory adaptations appeared within 4-days of acclimation and persisted 1-month afterwards.

Whether one acclimation strategy is better than the other is impossible to say based on current evidence, because while McIntyre et al. (2021) found that 6-days of daily post-exercise hot water immersion (40 -mins up-to-the-neck in 40 °C water) elicited larger thermal adaptations and better “hot performance” than daily exercise in the heat (60-min run in 33 °C), Carsten Lundby and colleagues (2021) found that “hot performance” was equally improved by 10-days of daily exercise in the heat (50-min ride in 35 °C), daily exercise (50-min ride) in thermal clothing, or daily exercise (50-min ride) followed by hot water immersion (~30-mins up-to-the-neck in 40°C water).

Fortunately, for the overall

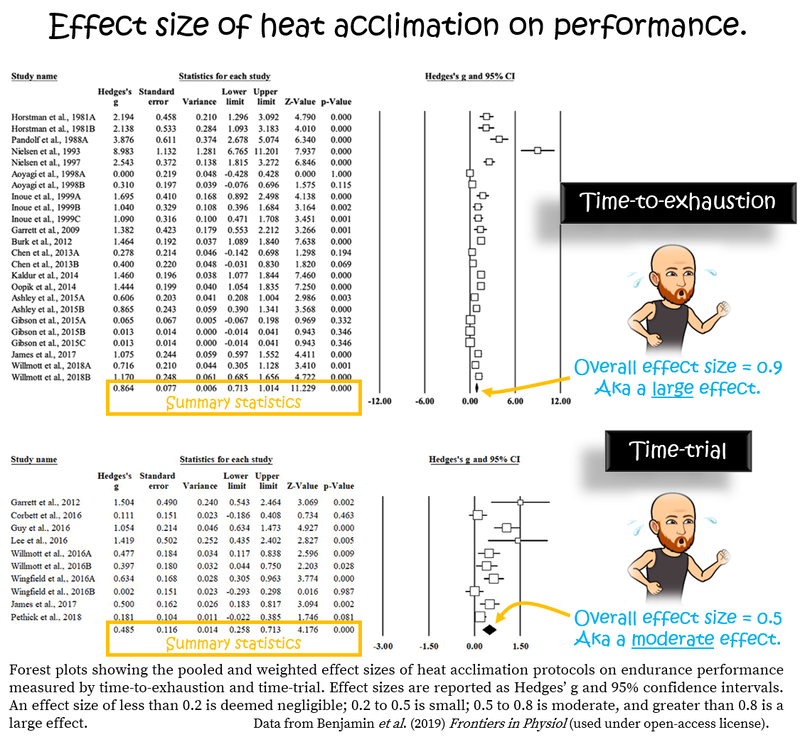

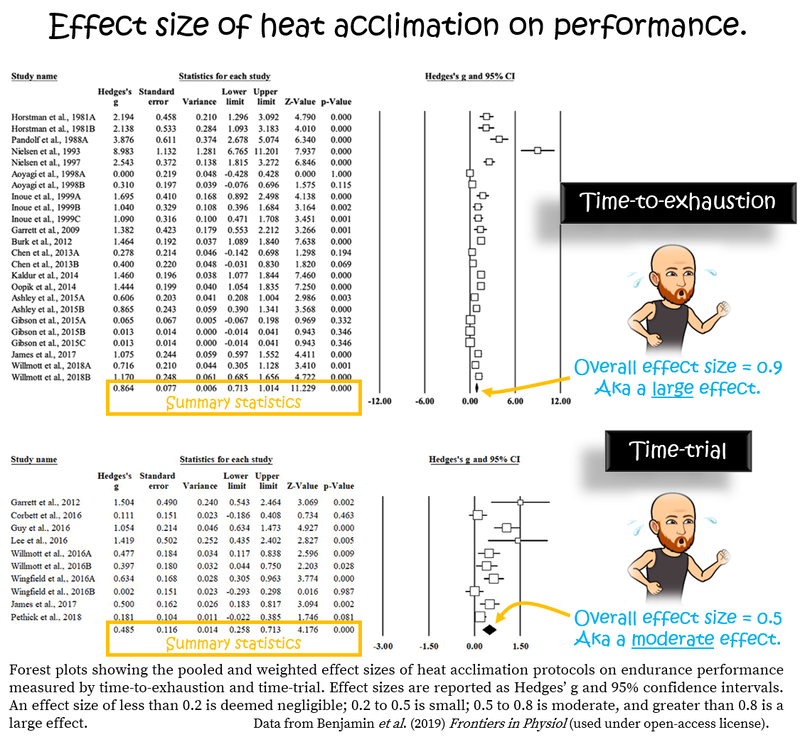

An early systematic review by Chalmers et al. concluded that 4 to 7 sessions in the heat over 5-10 days increases aerobic endurance but not anaerobic performance, although no meta-analysis of effect sizes was reported. In 2016, a meta-analysis by Tyler et al. confirmed that daily sessions in the heat (~30-40°C) had a moderate beneficial effect on performance in the heat (

Copyright © Benjamin et al. (2019) Frontiers in Physiol.. Open access licensed under Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY 4.0.

A 2021 trial from my old colleague Becky Lucas’s lab found that 3-weeks of heat acclimation (a 30-min post-exercise ~100°C dry-air sauna, 3x/wk) not only improved “hot performance” but also increased

In my opinion, the current evidence suggests that all athletes should consider heat acclimation even if they don’t intend to race in the heat. And, this doesn’t have to mean interrupting your training by exercising in a hot room — post-session heat exposure might be just as effective.

In my opinion, the current evidence suggests that all athletes should consider heat acclimation even if they don’t intend to race in the heat. And, this doesn’t have to mean interrupting your training by exercising in a hot room — post-session heat exposure might be just as effective.

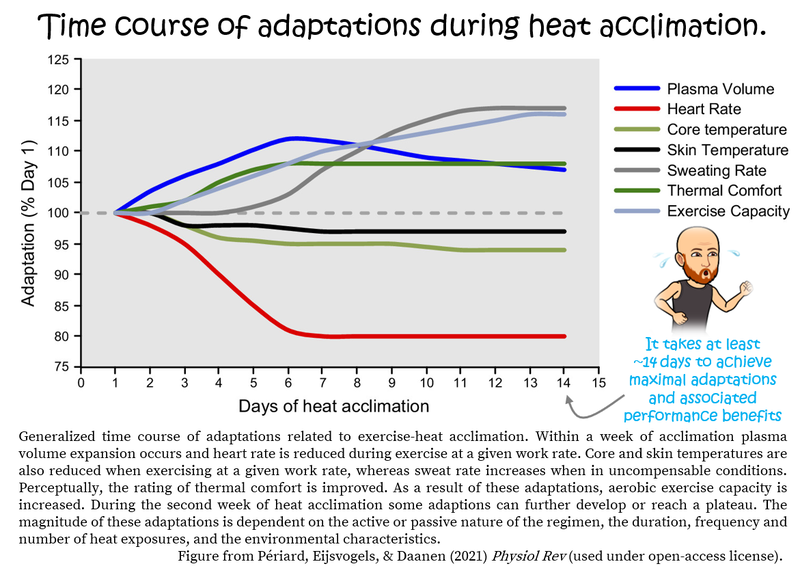

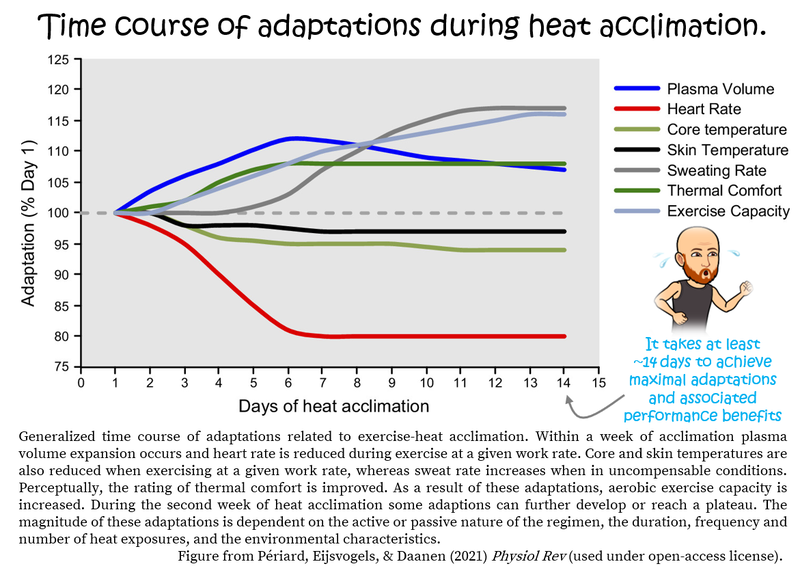

So, why not try a heat acclimation protocol ahead of your next race. If you live outside of Finland, you are far more likely to have access to a bathtub than a sauna. So, for most folks, a post-run lounge in a hot (40°C) bath is a more practical means of heat acclimation than a post-run sauna. But, whichever heat acclimatization/acclimation strategy you use, know that:

Heat adaptations can be rapid but are highly variable between folks — it takes at least ~2-weeks for all folks to achieve full adaptation and associated performance benefits.

Heat adaptations can be rapid but are highly variable between folks — it takes at least ~2-weeks for all folks to achieve full adaptation and associated performance benefits.

Furthermore, when using a heat-beating protocol, always be sure to manage hydration by drinking to thirst. Remember: if you are in a warm bath, sauna, or some kind of hot cave, bring fluid with you to stay hydrated! This will not neutralise your heat adaptations — staying hydrated will help you adapt optimally to your training — and all studies allowed participants to drink ab libitum during hot water immersion. It is also important to remember that neither heat acclimatization or acclimation is permanent — when you remove any regular (heat) stimulus, you lose your (heat) adaptations. But, a very cool 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis by Daanen et al. that examined heat acclimation decay and reintroduction, found that:

Improvements in cardiovascular strain, thermoregulation, and endurance performance following heat acclimation persist for 1–2 weeks and that the rate of adaptation during a subsequent heat re-acclimation is faster than the initial ~2-week acclimation period.

Improvements in cardiovascular strain, thermoregulation, and endurance performance following heat acclimation persist for 1–2 weeks and that the rate of adaptation during a subsequent heat re-acclimation is faster than the initial ~2-week acclimation period.

This means you could easily heat acclimate ahead of a race without disrupting your final taper.

Copyright © Périard, Eijsvogels, & Daanen (2021) Physiol Rev.. Open access licensed under Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY 4.0.

To put the effect size of heat acclimation into perspective, the

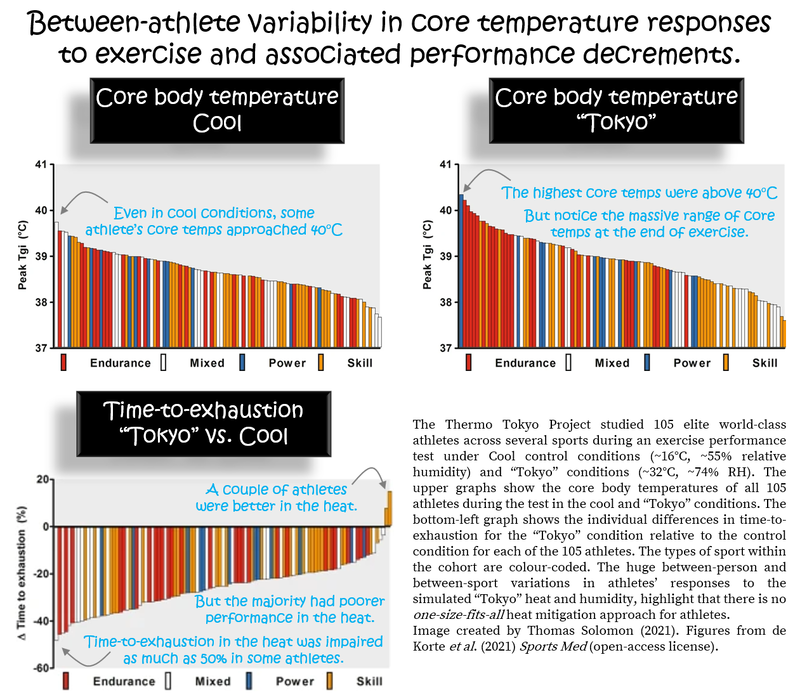

So, yep, you have many worthy options to “be cool”, like Travolta. But, you must conduct your N=1 experiments and use what works for you. The Thermo Tokyo Project, found that the rise in core temperature and the decrement in performance induced by heat and humidity are massively variable among world-class athletes (described in detail in Part 1), indicating that there is no one-size-fits-all heat-mitigating approach — athletes need a bespoke strategy for cooling, hydration, and “heat-beating” on race day. And, it is generally agreed that preventive heat adapting or heat mitigating countermeasures should be used in line with the specific demands of your sport.

If you wear glasses, they steam up so reading is nigh on impossible.

If you wear glasses, they steam up so reading is nigh on impossible.

A bottle of ice-cold water gets warm, fast.

A bottle of ice-cold water gets warm, fast.

It feels pretty rough after a workout when all you want to do is cool down but this feeling subsided after a few days.

It feels pretty rough after a workout when all you want to do is cool down but this feeling subsided after a few days.

The total time taken to complete a session plus post-session bathing becomes a little too much and won’t all folks’ schedules — you have to be efficient and choose in-bath productive tasks.

The total time taken to complete a session plus post-session bathing becomes a little too much and won’t all folks’ schedules — you have to be efficient and choose in-bath productive tasks.

Eating while lying neck-deep in water is tricky — much food ends up being hot water bathed and you’ll technically be lying in a post-exercise soup.

Eating while lying neck-deep in water is tricky — much food ends up being hot water bathed and you’ll technically be lying in a post-exercise soup.

But…

Determine whether your cardiovascular load is lower — is your HR and/or RPE during the run lower than it was before acclimation?

Determine whether your cardiovascular load is lower — is your HR and/or RPE during the run lower than it was before acclimation?

Determine whether your sweat rate is higher — is your body weight loss during the run greater than it was before acclimation?

Determine whether your sweat rate is higher — is your body weight loss during the run greater than it was before acclimation?

Determine whether your thermal comfort is higher — do you “feel” more comfortable during the run than before acclimation?

Determine whether your thermal comfort is higher — do you “feel” more comfortable during the run than before acclimation?

Simple. So...

01 Olympics. This gave athletes and their teams about 7 8-years notice to prepare for the biggest race of their lives in hot and humid conditions. At the Tokyo games, we saw many folks complain about the heat and, clearly, some folks had not prepared (which is regrettable because, as a professional athlete, it is literally your job to prepare immaculately for your target events). While some world-class endurance athletes are well adapted to the heat and have set their best times, even World Records, in hot conditions (see here, here, & here), some athletes also have intelligent teams around them. Ahead of Tokyo 20201, some national federations, like the Canadian Olympic Committee, planned exactly how best to help their athletes prepare... using heat acclimation and pre-race cold water immersion, along with during-race cooling strategies.

Canadian athletes keeping cool before their race in Tokyo.

Photo from Trent Stellingwerff’s Twitter feed @TStellingwerff.

Heat mitigating strategies are fairly autonomic during sessions/races — if you feel effing hot, you’re likely to throw something cold on your head, but only if you have something cold to throw. On the other hand, heat acclimation is far-less-intuitive and requires more planning, and is, therefore, far less used. For example, a huge study of 3317 runners competing in hot and sticky (~30°C, ~74% relative humidity) ultra races in France found that heat preparation strategies were highly-variable among runners — ~45% reported using a cooling strategy during their race, which primarily involved stopping or resting in the shade or cooling their head/neck with a wet sponge, while only ~24% of runners living in temperate climates reported having trained in the heat before their race.

At the super hot Doha 2019 World Athletics Championships, most athletes (80%) planned their pre-race cooling strategies, which included ice vests (53% of athletes), cold towels (45%), neck collars (21%) and ice slurry (21%), and/or their during-race cooling strategies (head/face dousing, 65%; and cold water ingestion, 52%), while menthol usage was negligible (1-2%). Importantly, pre-race core temperature was lower in athletes using ice vests (37.5°C±0.4°C vs 37.8°C±0.3°C, P=0.02) and pre-race skin temperature was higher in athletes caught by the DNF monster (33.8°C±0.9°C vs 32.6°C±1.4°C, P=0.02). Callum Hawkins, a pale-skinned, Caucasian dude from a beautiful land of abundant clouds, rain, and cold — Scotland — performed terrifically in the marathon in Doha, storming through the closing kilometres to finish 4th!

His prep?

Heat acclimation, logging tonnes of weekly miles on a treadmill in his shed with electric heaters. Callum Hawkins did his homework and prepared accordingly.

Pre-cooling and mid-cooling strategy during the World Athletics Championships.

Upper panel: percentage of athletes declaring to plan a pre/mid-cooling strategy. Lower panel: details of the strategy declared (in % of athletes). Getty images for World Athletics.

Image from Racinais et al. (2021) Br J Sports Med.

Some folks indeed prepare immaculately… At Tokyo 2020, ice vests, ice caps, and water pouring were commonplace at the front of the field in all the endurance races. During the men’s triathlon, from what the camera showed me, I counted Kristian Blummenfelt pouring 12 half-litre bottles of water (~6 Litres) over his head, shoulders, and arms on his way to taking gold. That’s the potential to evaporate ~3480 kcal (6 x 580 kcal) of heat energy away from his “burning” body — more than enough to account for the heat produced by his 1h45m of hell he endured to win Olympic gold. But other folks are not well-prepared — the sport during which there was widespread vocal dismay from players was tennis. Yet, the only heat mitigation strategy I saw players use was sitting under a radiation-blocking but heat-trapping and humidity-creating towel — don’t do that!

Instead, don’t make a racket (groan), “be less tennis; be more Hawkins and be more Blummenfelt” — educate yourself and then experiment with what works for you. If you live in a hot land, acclimatise by training in the heat. If you have access to a hot tub, sauna, or bathtub, use them for acclimation. You might only have one hot race a year or you might have a whole season of hot races. Either way, think carefully about how best you can either acclimatize naturally or acclimate artificially ahead of the event(s) and how you can use heat mitigation strategies to keep your cool.

During very short-duration sessions and races (e.g. up to 5-10-mins, you simply do not have enough time to raise your core temperature UNLESS it is already elevated to begin. During longer-duration sessions and races (i.e. longer than 5-10-mins), the quicker you “burn” the faster your core temp will rise and the longer you “burn”, the hotter the furnace will become . These scenarios elevate your risk of “overheating”, causing fatigue sooner than you want while increasing your risk of developing an exertional heat illness. So, rather than finishing a race and complaining that it was “too hot” why not prepare for the heat so that if the Sith Lord of fatigue, Darth Fader

. These scenarios elevate your risk of “overheating”, causing fatigue sooner than you want while increasing your risk of developing an exertional heat illness. So, rather than finishing a race and complaining that it was “too hot” why not prepare for the heat so that if the Sith Lord of fatigue, Darth Fader  , makes an appearance on a hot day, you can be confident that you “beat the heat” and that something else needs fixing… Therefore, a smart athlete will use strategies that slow down the rise in their core (and brain) temperature both before AND during exercise.

, makes an appearance on a hot day, you can be confident that you “beat the heat” and that something else needs fixing… Therefore, a smart athlete will use strategies that slow down the rise in their core (and brain) temperature both before AND during exercise.

In Part 2, I described the free (or very cheap) and highly-effective heat mitigation strategies that will help you stay cool on a hot and humid day. But, to further bolster your chance of race success on a hot and humid day, even if you are naturally acclimatized by living and training in a hot place, as a smart athlete you will also consider using a heat acclimation strategy. This will lower your cardiovascular strain and RPE, and improve your performance in the heat while not jeopardising (and possibly improving) your performance in cool conditions.

The simplest and effective way to achieve this without interrupting your training is to

Sit in a sauna, hot tub, or warm bath after your sessions every day for 2-weeks about 2-4 weeks before your “A” race.

Sit in a sauna, hot tub, or warm bath after your sessions every day for 2-weeks about 2-4 weeks before your “A” race.

You’d be silly not to try it. The only caveats are to

Stay aware of the signs of heat stress and exertional heat illness.

Stay aware of the signs of heat stress and exertional heat illness.

And to

Stay aware of your thirst and your need to drink fluid to quench it.

Stay aware of your thirst and your need to drink fluid to quench it.

Thanks for getting sweaty with me. Until next time, “Be cool”.

IMPORTANT: If you are pregnant and/or have any medical conditions, you should consult your doctor before exercising in hot conditions and/or considering using a heat acclimation strategy.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

The first thing you might not have guessed is that...

Your normal training improves your tolerance to heat stress.

As you learned in Part 1, the onset of sweat is important because sweating = cooling and the sooner you start sweating during exercise, the sooner you start cooling…. And this is one of the many “magical” adaptations you gain from a regular accumulation of purposeful exercise sessions — it is very well known that trained athletes start sweating sooner than untrained inactive folks. And by “sooner” I mean that athletes are more sensitive to a rise in their core body temperature and start sweating following a smaller rise in their core temperature. Furthermore, it is not that “fitter” people have better thermoregulatory responses to exercise (i.e. it is not simply having a higherV̇O2maxMaximal rate of oxygen consumption; a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness and maximal aerobic power, which contributes to endurance performance..

that helps), evidence shows that it is training that directly increases sweat rate and slows the increase in core temperature in the heat. That said, having a higher V̇O2max (being fitter) is associated with an attenuated age-related decline in thermoregulatory function during exercise in the heat. All the more reason to train well and to train up until you are too wrinkly, senile, dusty and grey to breathe any longer...

That your normal training improves your tolerance to an increasing core temperature during exercise is great but that is not what you came here to hear about… Surely, there is something more you can do?

“Naturally” acclimatizing and/or “artificially” acclimating to beat the heat?

IMPORTANT: If you are pregnant and/or have any medical conditions, you should consult your doctor before exercising in hot conditions and/or considering using a heat acclimation strategy.

Heat “acclimatization” is what happens when you train outdoors in hot weather, i.e. it is “natural”. Heat “acclimation” is what happens when you adapt following repeated exposure to an artificially hot environment (a hot tub, a sauna, a hot bath, etc). Either way, similar adaptations result… Increased plasma volume (due to increased kidney retention of sodium and better reabsorption of solutes in skin duct cells back into the blood), decreased resting heart rate, less cardiovascular strain during exercise, lower RPE, increased sweat rate at a lower core temperature and, therefore, you start sweating sooner during exercise (fully reviewed in Périard, Eijsvogels, & Daanen in Physiol Rev.).

So,

×

![]()

But, the important question is,

Secondly, since training camps are commonly held in hot places, it is important to know that thermoregulatory and performance adaptations following short-term heat acclimation training blocks are rapid. But, not only will you rapidly acquire the adaptations, thermoregulatory and performance benefits are retained for up to 2 to 4-weeks following heat acclimation. For example, Zurawlew et al. (2019) found that 5-days of daily 40-min running at 65%V̇O2max in ~20°C followed by hot water immersion (40 -mins up-to-the-neck in 40 °C water) improved thermoregulatory adaptations during running in the heat (40°C) that persisted for at least 2-weeks (reduced resting and end-exercise core temperature, faster sweating onset, & lower skin temp, heart rate, RPE, and thermal sensation). Meanwhile, Gerrett and colleagues (2021) found improved thermoregulation and performance after 10-days of daily cycling-in-the-heat (35-mins in 33°C) and that thermoregulatory adaptations appeared within 4-days of acclimation and persisted 1-month afterwards.

Whether one acclimation strategy is better than the other is impossible to say based on current evidence, because while McIntyre et al. (2021) found that 6-days of daily post-exercise hot water immersion (40 -mins up-to-the-neck in 40 °C water) elicited larger thermal adaptations and better “hot performance” than daily exercise in the heat (60-min run in 33 °C), Carsten Lundby and colleagues (2021) found that “hot performance” was equally improved by 10-days of daily exercise in the heat (50-min ride in 35 °C), daily exercise (50-min ride) in thermal clothing, or daily exercise (50-min ride) followed by hot water immersion (~30-mins up-to-the-neck in 40°C water).

Fortunately, for the overall

effect sizesa quantitative measure of the magnitude of the experimental effect. Less than 0.2 is no effect, 0.2 to 0.5 is small, 0.5 to 0.8 is moderate, greater than 0.8 is large.

of heat acclimatization and acclimation protocols, systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide clarity...

An early systematic review by Chalmers et al. concluded that 4 to 7 sessions in the heat over 5-10 days increases aerobic endurance but not anaerobic performance, although no meta-analysis of effect sizes was reported. In 2016, a meta-analysis by Tyler et al. confirmed that daily sessions in the heat (~30-40°C) had a moderate beneficial effect on performance in the heat (

Hedges’ g=0.63a type of effect size that quantities the average change score relative to the standard deviation (i.e. the range) of the change scores.

; 95%CI 0.46–0.79the 95% CI is a range of values within which the true value would be found 95% of the time if the data was repeatedly collected in different samples of people.

), where longer acclimation periods (≥14-days) were more effective than shorter (<14-days) approaches. Similarly, a 2019 meta-analysis by Benjamin et al. found that daily sessions in the heat improve both time-to-exhaustion (large effect: g=0.86; 95%CI 0.71-1.0) and time-trial performance (moderate effect: g=0.5; 95%CI 0.26-0.71), while another 2019 meta-analysis by Rahimi et al. pooled daily sessions in the heat and daily post-session hot water immersion strategies, finding a moderate effect of heat acclimation on time-trial endurance performance (Cohen’s d=0.5a type of effect size that quantities the average change score relative to the standard deviation (i.e. the range) of the change scores.

; 95%CI 0.03-0.97the 95% CI is a range of values within which the true value would be found 95% of the time if the data was repeatedly collected in different samples of people.

). However, a major limitation of the current evidence is the lack of ecologically-valid performance tests — most studies use a time-to-exhaustion at a moderate intensity in the lab; few studies use a time-trial, and no studies use an outdoor/race-like model of performance (a common limitation across all of exercise science).

×

![]()

So, heat acclimation will clearly bolster your “hot performance” but what about performance in temperate conditions?

A 2021 trial from my old colleague Becky Lucas’s lab found that 3-weeks of heat acclimation (a 30-min post-exercise ~100°C dry-air sauna, 3x/wk) not only improved “hot performance” but also increased

V̇O2maxMaximal rate of oxygen consumption; a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness and maximal aerobic power, which contributes to endurance performance..

and running speed at 4 mmol/L lactate in 18°C in trained runners. Furthermore, a 2021 study from another former colleague, Ed Maunder, found that 3-weeks of endurance training in 33°C more greatly improved 30-min time-trial performance in 18°C than identical training performed in 18°C. Such findings have been collated and a 2021 meta-analysis by Waldron et al. found small to moderate beneficial effect of daily sessions in the heat on V̇O2maxMaximal rate of oxygen consumption; a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness and maximal aerobic power, which contributes to endurance performance..

measured in cool conditions (small effect: g=0.30, 95%CI 0.06–0.54) (and hot conditions (moderate effect: g=0.75, 95%CI 0.22–1.27)), with a greater number of acclimation days and higher during-session temperature predicting bigger improvements in V̇O2max. (Note that the study by Waldron et al. uses the phrases acclimation & acclimatisation interchangeably but only included acclimation papers that used daily exercise in the heat.) Whether this effect is a direct result of the increased cardiovascular strain caused by heat exposure or the ability to keep core temp lower for longer and therefore resist fatigue for longer is unclear. Either way,

×

![]()

Note: For a phenomenally deep-dive into this topic, I recommend reading the 2021 narrative review Exercise under heat stress: thermoregulation, hydration, performance implications, and mitigation strategies by Périard, Eijsvogels, & Daanen in Physiol Rev..

Putting heat acclimation into practice.

A 2019 meta-analytical attempt to compare heat adaptation and heat mitigation strategies by Alhadad et al. found that heat acclimation has a superior effect on endurance performance than pre-exercise cooling, during-exercise cooling, or during-exercise hydration (but there are many limitations of such a comparative approach). Nonetheless, consensus recommendations published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine also tout using heat acclimation prior to a target competition (i.e. before an “A” race) coupled with adequate hydration and pre- and during-exercise cooling strategies. Furthermore, the 2007 American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) position stand on exertional heat illness during training and competition recommends familiarising with exercise in the heat (i.e. acclimation) to reduce the risk of heat illness.To put the effect size of heat acclimation into perspective, the

standard deviationa measure of spread around the mean value (the average value).

of the mens’ finish times at the disgustingly hot (28°C with 72% relative humidity) men’s marathon at Tokyo 2020, was 366-seconds (6m06s) with 76 finishers ranging from 2:08:38 (Eliud Kipchoge) to 2:44:36. Based on the most recent meta-analysis by Benjamin et al., the effect sizea quantitative measure of the magnitude of the experimental effect. Less than 0.2 is no effect, 0.2 to 0.5 is small, 0.5 to 0.8 is moderate, greater than 0.8 is large.

for heat acclimation on time-trial performance is 0.5 standard deviations, equivalent to a performance improvement of 183 seconds (3m03s) in Tokyo. Consequently, any athlete who finished who finished in 2:11:41 or faster (the 2nd to 8th place finishers), might have beaten Kipchoge and won gold if they heat acclimated before the race. Once again, similar to my theoretical analysis on during-race cooling in Part 2, this is a big might and I make the assumption that these competitors did not heat acclimate, which is foolish.

So, yep, you have many worthy options to “be cool”, like Travolta. But, you must conduct your N=1 experiments and use what works for you. The Thermo Tokyo Project, found that the rise in core temperature and the decrement in performance induced by heat and humidity are massively variable among world-class athletes (described in detail in Part 1), indicating that there is no one-size-fits-all heat-mitigating approach — athletes need a bespoke strategy for cooling, hydration, and “heat-beating” on race day. And, it is generally agreed that preventive heat adapting or heat mitigating countermeasures should be used in line with the specific demands of your sport.

×

![]()

What I learned from post-exercise hot water bathing.

I have reccied a 2-week block of daily post-session hot bathing (I never prescribe anything to my athletes that I have not tried). There were some surprising findings:How do you know if your heat acclimation strategy is working?

Well, it is always very difficult to pinpoint which specific stimulus was the cause of the boost (or fall) in your performance. But, to crudely test whether your heat acclimation strategy has worked, there are three very simple things you can measure during a steady state run at the same pace in the same conditions, before and after your acclimation period:How do real people beat the heat?

In September 2013, the IOC announced that Tokyo would host the 202

Photo from Trent Stellingwerff’s Twitter feed @TStellingwerff.

×

![]()

Some of you will simply hate exercising in the heat — an emotive response to heat that slows you down. Some of you will poorly tolerate exercising in the heat — a lack of an appropriate physiological response to the heat. Others of you may fail to stay cool, either because your sweat does not evaporate or because you do not keep your skin cool. However, some of you folks are probably fine in the heat and perhaps don’t even notice it. Personally, I hate being in the heat at rest — sweating when I'm sitting or lying down just pisses me off! But, running in the heat... I’m fine — my sweat response is fast, my sweat rate is high, and my emotive response is positive — yay!

Heat mitigating strategies are fairly autonomic during sessions/races — if you feel effing hot, you’re likely to throw something cold on your head, but only if you have something cold to throw. On the other hand, heat acclimation is far-less-intuitive and requires more planning, and is, therefore, far less used. For example, a huge study of 3317 runners competing in hot and sticky (~30°C, ~74% relative humidity) ultra races in France found that heat preparation strategies were highly-variable among runners — ~45% reported using a cooling strategy during their race, which primarily involved stopping or resting in the shade or cooling their head/neck with a wet sponge, while only ~24% of runners living in temperate climates reported having trained in the heat before their race.

At the super hot Doha 2019 World Athletics Championships, most athletes (80%) planned their pre-race cooling strategies, which included ice vests (53% of athletes), cold towels (45%), neck collars (21%) and ice slurry (21%), and/or their during-race cooling strategies (head/face dousing, 65%; and cold water ingestion, 52%), while menthol usage was negligible (1-2%). Importantly, pre-race core temperature was lower in athletes using ice vests (37.5°C±0.4°C vs 37.8°C±0.3°C, P=0.02) and pre-race skin temperature was higher in athletes caught by the DNF monster (33.8°C±0.9°C vs 32.6°C±1.4°C, P=0.02). Callum Hawkins, a pale-skinned, Caucasian dude from a beautiful land of abundant clouds, rain, and cold — Scotland — performed terrifically in the marathon in Doha, storming through the closing kilometres to finish 4th!

His prep?

Heat acclimation, logging tonnes of weekly miles on a treadmill in his shed with electric heaters. Callum Hawkins did his homework and prepared accordingly.

Upper panel: percentage of athletes declaring to plan a pre/mid-cooling strategy. Lower panel: details of the strategy declared (in % of athletes). Getty images for World Athletics.

Image from Racinais et al. (2021) Br J Sports Med.

×

![]()

Yes, it can be tough to acclimate to truly beat the heat but, with the plethora of effective heat mitigating and heat acclimating strategies available, it is not impossible. After championship races in predictably tough conditions, it is common to hear professional athletes complain that it was “too hot” or “too humid”. Then, when you dig into their preparation, it is also extremely common to find that said athletes did next to nothing to help themselves prepare for the heat on race day. The World Athletics Championships in Doha was a good example, as was the Athens Olympics in 2004, and Tokyo 2020 was no different.

Some folks indeed prepare immaculately… At Tokyo 2020, ice vests, ice caps, and water pouring were commonplace at the front of the field in all the endurance races. During the men’s triathlon, from what the camera showed me, I counted Kristian Blummenfelt pouring 12 half-litre bottles of water (~6 Litres) over his head, shoulders, and arms on his way to taking gold. That’s the potential to evaporate ~3480 kcal (6 x 580 kcal) of heat energy away from his “burning” body — more than enough to account for the heat produced by his 1h45m of hell he endured to win Olympic gold. But other folks are not well-prepared — the sport during which there was widespread vocal dismay from players was tennis. Yet, the only heat mitigation strategy I saw players use was sitting under a radiation-blocking but heat-trapping and humidity-creating towel — don’t do that!

Instead, don’t make a racket (groan), “be less tennis; be more Hawkins and be more Blummenfelt” — educate yourself and then experiment with what works for you. If you live in a hot land, acclimatise by training in the heat. If you have access to a hot tub, sauna, or bathtub, use them for acclimation. You might only have one hot race a year or you might have a whole season of hot races. Either way, think carefully about how best you can either acclimatize naturally or acclimate artificially ahead of the event(s) and how you can use heat mitigation strategies to keep your cool.

Note: for a phenomenal dive into the literature on all things related to exercise in the heat, including performance implications, and mitigation strategies, I thoroughly recommend reading a 2021 narrative review from Julien Périard, Thijs Eijsvogels, and Hein Daanen (2021) Physiol Rev. And, for an interesting listen on this topic, I can recommend Shawn Bearden’s Science of Ultra interview with Dr Chris Minson and Ross Tucker’s Science of Sport podcast on the World Athletics champs in Doha.

What can you add to your training cool box?

You will reach fatigue during exercise in the heat at a specific core temperature unique to you. Increasing your pre-exercise core temperature or the rate of increase of your core temperature, simply means you reach your thermal threshold quicker. Therefore, aim to start cool and be cool.During very short-duration sessions and races (e.g. up to 5-10-mins, you simply do not have enough time to raise your core temperature UNLESS it is already elevated to begin. During longer-duration sessions and races (i.e. longer than 5-10-mins), the quicker you “burn” the faster your core temp will rise and the longer you “burn”, the hotter the furnace will become

In Part 2, I described the free (or very cheap) and highly-effective heat mitigation strategies that will help you stay cool on a hot and humid day. But, to further bolster your chance of race success on a hot and humid day, even if you are naturally acclimatized by living and training in a hot place, as a smart athlete you will also consider using a heat acclimation strategy. This will lower your cardiovascular strain and RPE, and improve your performance in the heat while not jeopardising (and possibly improving) your performance in cool conditions.

The simplest and effective way to achieve this without interrupting your training is to

And to

IMPORTANT: If you are pregnant and/or have any medical conditions, you should consult your doctor before exercising in hot conditions and/or considering using a heat acclimation strategy.

×

![]()

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.