Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — Plan your training.

→ Part 2 — Design your training.

→ Part 3 — Review your training.

→ Part 1 — Plan your training.

→ Part 2 — Design your training.

→ Part 3 — Review your training.

Be the architect of your training. Part 1 of 3:

Plan your training.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

29th Nov 2019.

In this three-part series, I dive a little deeper into my philosophy of training through the use of anecdotes and observations made during my own journey as an academic, coach, and athlete. To help you lead your own training, take inspiration from the path of an architect, by planning, designing, and reviewing. Here in Part 1 of the series, I delve into what training is and how to start planning it.

Reading time ~10-mins (1900-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

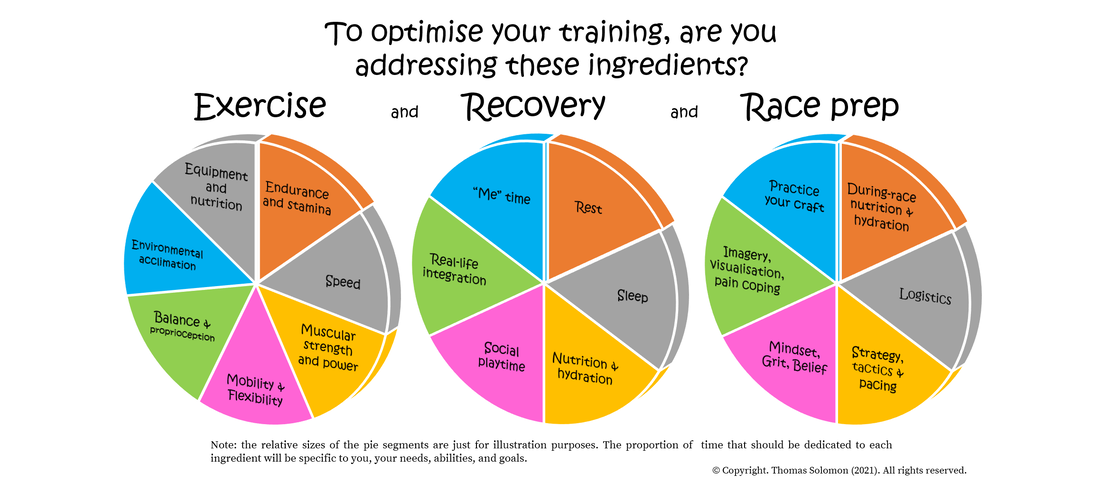

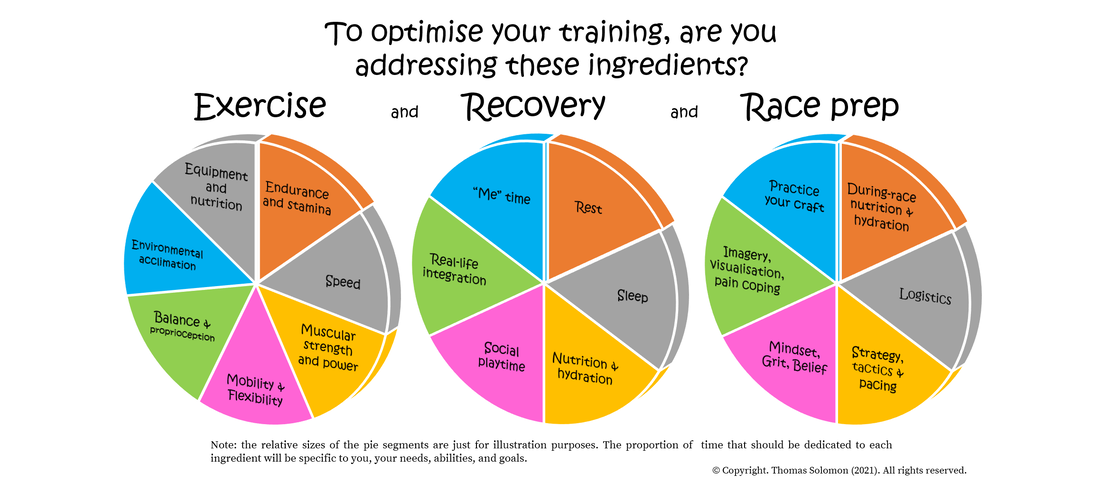

We are all an “N of one” with inherently-defined capacities for growth and adaptations to the specific stimuli to which we are exposed or that we impose on ourselves. Understanding our own nuances is vital for maximising the desired outcomes following a series of specifically-imposed demands. To know where to begin, one must understand that training consists of two equally important components: exercise and recovery. As you will see in the diagram, these two components rather simply break down the philosophy of “stress, rest, adapt, grow, while being patient, staying calm, and having fun” discussed in my previous post.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I like to conceptualise training as a pie of two layers, one layer containing the ingredients of recovery, including rest, sleep, nutrition, playtime, real-life integration, and “me” time, with the other layer consisting of the ingredients of exercise, including sessions aimed at endurance, speed, power, flexibility, balance, acclimation, and equipment and nutrition. If an ingredient is removed, the training approach may not progress with success. At a glance, these ingredients of the basic training pie might seem all too obvious and very simple. Alas, many people must be coached by Jason Biggs because the pie gets “American Pie-ed” far too frequently. In fact, it is very common to see these ingredients become abbreviated to an oversimplified and erroneous notion: run every day, ideally as fast as you can, and move the heaviest objects you can find, all the time. Please, do not do that. Instead, aim for a sensible and holistic approach. To keep things simple, perhaps consider the following framework as a checklist for facilitating success:

Rattling around in my brain is the mantra that “training smart beats talent when talent doesn’t train smart”. Rooted in my belief in this notion are the many “talented” athletes who are seemingly perpetually-injured and/or under-performing. Is it because they are neglecting too many components of holistic training? Possibly. First-hand evidence that converts this “possibly” into a “yes”, comes from the prior training diaries of many folks who have sought my advice or coaching. But evidence of bad habits also very simply presents itself in people’s online training records, despite the widespread availability of position stands, recommendations, advice, and guidance.

So, what goes wrong?

Well, here are my oh-so-frequent observations:

Having an ill-defined goal.

Having an ill-defined goal.

Training too hard, too often, with too much too soon.

Training too hard, too often, with too much too soon.

A disregard for the importance and necessity of recovery.

A disregard for the importance and necessity of recovery.

Training stimuli that lack consistency.

Training stimuli that lack consistency.

No evidence of progression.

No evidence of progression.

Sessions that lack clarity of purpose.

Sessions that lack clarity of purpose.

A lack of variety or “range”.

A lack of variety or “range”.

Indeed, if these errors are deep-rooted, change is a challenge but never impossible. To set yourself up with a clear, holistic, and healthy approach to your training that avoids the above-described faux pas, there is something very simple you can do. Learn from the example of an architect: plan, design, and review your training. In Part 1 of this journey, I will discuss the planning phase.

Set a goal. Without a goal (or a set of goals) it is impossible to understand your needs and therefore it is impossible to know where to begin with your design. To help with this and to motivate your commitment to your training as well as maximise your adherence, set yourself a SMART goal. Your goal should be Specific, Measurable (or quantifiable), Ambitious, Realistic, and have a Time-frame. You can be bold and optimistic, but also be pragmatic. For example, if you have trained consistently for several years and have a 5 km road PB of 16-minutes, it is highly unlikely you have the genetic gifts that can be honed into taking 2-minutes off your 5km time. Similarly, if you possess an all-time 5km road PB of 16-minutes after years of consistent training and now wish to focus on OCR racing, your training will not be specific to the 5 km, you will not often be racing the 5 km, and so it is highly unlikely that you will improve your 5 km PB. You might, however, increase your absolute strength making the art of moving a 30 kg bucket carry more efficient and easier to recover from and, therefore, helping you get back up to a high running speed more rapidly.

Set a goal. Without a goal (or a set of goals) it is impossible to understand your needs and therefore it is impossible to know where to begin with your design. To help with this and to motivate your commitment to your training as well as maximise your adherence, set yourself a SMART goal. Your goal should be Specific, Measurable (or quantifiable), Ambitious, Realistic, and have a Time-frame. You can be bold and optimistic, but also be pragmatic. For example, if you have trained consistently for several years and have a 5 km road PB of 16-minutes, it is highly unlikely you have the genetic gifts that can be honed into taking 2-minutes off your 5km time. Similarly, if you possess an all-time 5km road PB of 16-minutes after years of consistent training and now wish to focus on OCR racing, your training will not be specific to the 5 km, you will not often be racing the 5 km, and so it is highly unlikely that you will improve your 5 km PB. You might, however, increase your absolute strength making the art of moving a 30 kg bucket carry more efficient and easier to recover from and, therefore, helping you get back up to a high running speed more rapidly.

Consider the needs of your event to help identify the purpose of your sessions. Following the recent popularity of short high-intensity interval training (or SHIT), it is particularly common to find folks trying to train for endurance events with nothing but SHIT. Typically, these folks tend to detonate hard during events lasting more than an hour. Neglecting volume solely in favour of intensity will make you pretty darn shit at long-distance endurance events. Yes, if you are a newbie or someone who trains infrequently, throwing any exercise stimulus into the mix will improve your fitness; as the saying goes, “if you throw SHIT at the wall, some of it will stick”. But as a performance athlete seeking success in endurance events, a diet solely consisting of SHIT will not taste good come race day. A good architect will make a needs analysis; identify your needs. If you are an endurance athlete, you will need some volume.

Consider the needs of your event to help identify the purpose of your sessions. Following the recent popularity of short high-intensity interval training (or SHIT), it is particularly common to find folks trying to train for endurance events with nothing but SHIT. Typically, these folks tend to detonate hard during events lasting more than an hour. Neglecting volume solely in favour of intensity will make you pretty darn shit at long-distance endurance events. Yes, if you are a newbie or someone who trains infrequently, throwing any exercise stimulus into the mix will improve your fitness; as the saying goes, “if you throw SHIT at the wall, some of it will stick”. But as a performance athlete seeking success in endurance events, a diet solely consisting of SHIT will not taste good come race day. A good architect will make a needs analysis; identify your needs. If you are an endurance athlete, you will need some volume.

Identify your strengths and weaknesses. Write a list of what you are good at. Make sure you plan to consolidate and exploit those merits. Now, identify your kryptonite; make a list of your weaknesses. Plan to overcome them; turn them into strengths. Now consider these lists of factors in line with the needs of your event. Some clarity will emerge...

Identify your strengths and weaknesses. Write a list of what you are good at. Make sure you plan to consolidate and exploit those merits. Now, identify your kryptonite; make a list of your weaknesses. Plan to overcome them; turn them into strengths. Now consider these lists of factors in line with the needs of your event. Some clarity will emerge...

Take responsibility and be accountable. It is not necessary to become a “strava”-slave but it can be very useful to log your training in some form along with weekly or even daily notes about how well prepared you were for key sessions, how well they went, and how you felt afterwards. This can help track your progress, help you be accountable for what you are doing, and help identify patterns that align with feeling good or bad for specific quality sessions.

Take responsibility and be accountable. It is not necessary to become a “strava”-slave but it can be very useful to log your training in some form along with weekly or even daily notes about how well prepared you were for key sessions, how well they went, and how you felt afterwards. This can help track your progress, help you be accountable for what you are doing, and help identify patterns that align with feeling good or bad for specific quality sessions.

Identify how much time you have. Which days can you commit? How much time can you commit each day. Be realistic. It doesn't matter what you plan to do if it doesn't fit in with real life. You need time for work, sleep, meals, rest, playtime, family time, etc etc. Use a time-planner or calendar to find a regular schedule of time blocks. This will help make your training work for you and will help you be realistic about the total training load your real life can handle.

Identify how much time you have. Which days can you commit? How much time can you commit each day. Be realistic. It doesn't matter what you plan to do if it doesn't fit in with real life. You need time for work, sleep, meals, rest, playtime, family time, etc etc. Use a time-planner or calendar to find a regular schedule of time blocks. This will help make your training work for you and will help you be realistic about the total training load your real life can handle.

Make time and space for your key sessions. This includes time for the prep, time for the work-out itself, and time for the recovery from the work-out. A long hard run can completely obliterate your body and mind for a few hours afterwards, necessitating a focus on good nutrition, rehydration, and rest - remember to factor that truth into the day surrounding such a workout.

Make time and space for your key sessions. This includes time for the prep, time for the work-out itself, and time for the recovery from the work-out. A long hard run can completely obliterate your body and mind for a few hours afterwards, necessitating a focus on good nutrition, rehydration, and rest - remember to factor that truth into the day surrounding such a workout.

Allow for some flexibility in your design. Unless you are a professional athlete, your training is unlikely to be your sole priority and real-life events will frequently become an obstacle. If you must miss a session, do not panic. No single session defines your fitness. You are on a journey. Just like any journey, you may encounter delays. Stay calm, and like Forrest Gump taught us, “Shit”, “It happens”, “sometimes”. So, if you need to rest, rest; if you need to cut-short, abort mission. Be like Gump; allow for some flexibility, re-group and just keep on running.

Allow for some flexibility in your design. Unless you are a professional athlete, your training is unlikely to be your sole priority and real-life events will frequently become an obstacle. If you must miss a session, do not panic. No single session defines your fitness. You are on a journey. Just like any journey, you may encounter delays. Stay calm, and like Forrest Gump taught us, “Shit”, “It happens”, “sometimes”. So, if you need to rest, rest; if you need to cut-short, abort mission. Be like Gump; allow for some flexibility, re-group and just keep on running.

Always remember that you can say yes to that beer. Your brain needs social interaction with people, real people, in person. Your exercise adaptations won’t be impeded by being social unless alcohol is involved immediately after a session. Put down that device, stop staring at people online, and go join your friends or family for some playtime.

Always remember that you can say yes to that beer. Your brain needs social interaction with people, real people, in person. Your exercise adaptations won’t be impeded by being social unless alcohol is involved immediately after a session. Put down that device, stop staring at people online, and go join your friends or family for some playtime.

Make recovery the best session of every week. Learn to embrace recovery as the most important component of your training and not simply as something that magically happens in between exercise sessions. I encourage everyone to invest resources into making their recovery from exercise as high-quality as possible. It is important to realise that “to recover” is not simply what you do when you sit down between sessions. Being patient, staying calm, having fun, eating, sleeping, resting, relaxing, meditating are all important facets of recovery when you are not exercising. Think about how you address these in your training.

Make recovery the best session of every week. Learn to embrace recovery as the most important component of your training and not simply as something that magically happens in between exercise sessions. I encourage everyone to invest resources into making their recovery from exercise as high-quality as possible. It is important to realise that “to recover” is not simply what you do when you sit down between sessions. Being patient, staying calm, having fun, eating, sleeping, resting, relaxing, meditating are all important facets of recovery when you are not exercising. Think about how you address these in your training.

Start embedding the mindset that you will rest when you need to rest. No single missed session will ruin your fitness. Learn to be self-aware. Listen to your body. Learn to know when to rest. Don’t rely on gadgets and devices to tell you when enough is enough; your brain processes all feedback whether it be emotional or physiological, allowing you to answer very simple questions, like “how do I feel?”. To help with such decisions, you are very welcome to use my simple training decision tool. But rest is not only for when you are feeling like you’ve worked too hard. Rest is an integral part of recovery and, unlike pedigree sledge-racing malamutes who adapt to exercise while exercising, we, unfortunately, do not. Once in a while, we must sit down and stop moving. So, plan to build rest into your training. Rest your body, rest your mind. Be calm. If you are into meditation and mindfulness, schedule such sessions into your training. If you are yet to nestle a pair of big woollen socks carefully into your sandals, then just sit down in a quiet space, close your eyes, listen to your breathing and think about how you feel, right now, in the moment. There you go, you are already meditating, you hippie.

Start embedding the mindset that you will rest when you need to rest. No single missed session will ruin your fitness. Learn to be self-aware. Listen to your body. Learn to know when to rest. Don’t rely on gadgets and devices to tell you when enough is enough; your brain processes all feedback whether it be emotional or physiological, allowing you to answer very simple questions, like “how do I feel?”. To help with such decisions, you are very welcome to use my simple training decision tool. But rest is not only for when you are feeling like you’ve worked too hard. Rest is an integral part of recovery and, unlike pedigree sledge-racing malamutes who adapt to exercise while exercising, we, unfortunately, do not. Once in a while, we must sit down and stop moving. So, plan to build rest into your training. Rest your body, rest your mind. Be calm. If you are into meditation and mindfulness, schedule such sessions into your training. If you are yet to nestle a pair of big woollen socks carefully into your sandals, then just sit down in a quiet space, close your eyes, listen to your breathing and think about how you feel, right now, in the moment. There you go, you are already meditating, you hippie.

Well, that is the end of Part 1 on this three-part journey. You will now be armed with some skills to start your planning phase.

Thanks for reading and see you next time for further tips on becoming an architect of your training. In the meantime, stay active and keep training smart.

×

![]()

I like to conceptualise training as a pie of two layers, one layer containing the ingredients of recovery, including rest, sleep, nutrition, playtime, real-life integration, and “me” time, with the other layer consisting of the ingredients of exercise, including sessions aimed at endurance, speed, power, flexibility, balance, acclimation, and equipment and nutrition. If an ingredient is removed, the training approach may not progress with success. At a glance, these ingredients of the basic training pie might seem all too obvious and very simple. Alas, many people must be coached by Jason Biggs because the pie gets “American Pie-ed” far too frequently. In fact, it is very common to see these ingredients become abbreviated to an oversimplified and erroneous notion: run every day, ideally as fast as you can, and move the heaviest objects you can find, all the time. Please, do not do that. Instead, aim for a sensible and holistic approach. To keep things simple, perhaps consider the following framework as a checklist for facilitating success:

| Component of your training | Are you addressing these factors? | |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise = stress |

Endurance. | Progress to running lots of kilometres. |

| Speed. | Some of them quickly. | |

| Muscular strength and power. | Progress to move heavy objects, sometimes rapidly. | |

| Flexibility and mobility. | Learn to move and flow like Bruce Lee, without all the punching. | |

| Balance and proprioception. | Become an Ibex, minus the horns. | |

| Grip strength. | Become Alex Honnold, but perhaps use a rope. | |

| Environmental acclimation. | Become a Tardigrade and be resilient to heat, cold, altitude, and water immersion. | |

| Equipment and nutrition. | Become a Sherpa - know exactly what to bring, how to carry it, and when to use it - bags, belts, poles, energy, fluid. | |

| Recovery = rest, adapt, grow, while being patient, staying calm, and having fun. |

Rest. | Until the next session. |

| Sleep. | Rediscover your teenagehood - sleep a lot, sleep well. | |

| Nutrition and hydration. | Fuel your demands with high-quality and timely nutrient intake. | |

| Social playtime. | Engage in non-exercise related funtivities. | |

| Real-life integration. | Find a happy balance between work, people, and training, with an emphasis on people. | |

| “Me” time - calm, mindfulness, meditation. | Treat your mind well. It is in control. Healthy mind; strong body. | |

| Race prep = be prepared for race day. |

Practice your craft.. | Technique, climbing, descending, steeple barriers, obstacles, etc.. |

| During-race nutrition and hydration. | Fuel your demands with timely food and fluid intake. Practice in training. Find what you like. | |

| Logistics. | Registration, travel, sleep, jet lag, etc. | |

| Strategy, tactics & pacing. | How will you win? | |

| Mindset, grit, belief, imagery, visualisation, pain coping. | Psychology 101. Get your mind in the game. | |

Rattling around in my brain is the mantra that “training smart beats talent when talent doesn’t train smart”. Rooted in my belief in this notion are the many “talented” athletes who are seemingly perpetually-injured and/or under-performing. Is it because they are neglecting too many components of holistic training? Possibly. First-hand evidence that converts this “possibly” into a “yes”, comes from the prior training diaries of many folks who have sought my advice or coaching. But evidence of bad habits also very simply presents itself in people’s online training records, despite the widespread availability of position stands, recommendations, advice, and guidance.

So, what goes wrong?

Well, here are my oh-so-frequent observations:

Part 1: Plan your training.

Well, that is the end of Part 1 on this three-part journey. You will now be armed with some skills to start your planning phase.

Thanks for reading and see you next time for further tips on becoming an architect of your training. In the meantime, stay active and keep training smart.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Driftline and Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.