Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — Plan your training.

→ Part 2 — Design your training.

→ Part 3 — Review your training.

→ Part 1 — Plan your training.

→ Part 2 — Design your training.

→ Part 3 — Review your training.

Be the architect of your training. Part 2 of 3:

Design your training.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

2nd Dec 2019.

In the previous part of this three-part series of articles, I outlined the two components of training — exercise and recovery — and thereby gave some clues as to how you can begin to plan your training. In this second part, I will provide insight into your run towards becoming an architect by digging into the design phase of your journey.

Reading time ~15-mins (2800-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

During Part 1, the starting point was to set a goal and then to consider the needs of your event in relation to your strengths and weaknesses. That starting point is the backbone that will help you identify what key workouts you may need to succeed with your goal. It is prudent to prioritise your key workouts by making the time and space in your life for them while also aiming not to neglect the easy days and recovery days; get it right every day. Yes, rest when you need to rest yet additionally learn to embrace recovery as an integral part of your training. At the same time, allow for some flexibility when life goes awry and always allow for some relaxation and playtime.

To continue your architecture education, here in Part 2 I will delve into how you might optimise your training design. The purpose of this article is not to tell you how many times a week to train, how many kilometres to run, or how much weight to lift since those variables are unique to you. Instead, my aim is to arm you with additional tools with which to become knowledgeable in safe and effective design.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Training too hard, too often, are two ingredients for the perfect storm. The eye of that storm can then very quickly be found by doing too much too soon before your body has adapted to prior loads and before it is ready for greater demands. When you track down the training weeks of top endurance athletes, it may look like they run 160 kilometres (100 miles) a week at phenomenal speeds. But, it is all relative. If your marathon pace is 2:55 per kilometre (4:40 per mile) and you are very much accustomed to running 160 kilometres (100 miles) a week, popping out for a pre-breakfast 16 km (10 mile) run at 3:45 per km (6:00 per mile) is literally no sweat, even though to others that may seem incredibly quick. Do not simply copy what others are doing; it most likely won’t work for you. Instead, learn from the habits of “successful” others. I grew up in the 90s on the London-Surrey border, training at Kingsmeadow track, Richmond Park, and Bushey Park. The pleasure in this upbringing was not being able to rock my socks off whenever Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, or Rage Against the Machine came to London but in that my training locations were where Kenyan athletes used to train during their summer track season. Watching these folks effortlessly tick off eternal 55-second 400-repeats was something my ginger brain found pretty tough to handle. Nonetheless, it was actually watching them on their easy days that really made my ginger hair wither in astonishment. It was common to see them bouncing along around the streets of Teddington at 5 to 6-mins/km (8 to 10-minutes per mile). At the age of 17, this was my first introduction to “go easy on easy days”, a concept that the athletes and coaches surrounding me at the time seemingly misunderstood. Be more Kenyan.

Training too hard, too often, are two ingredients for the perfect storm. The eye of that storm can then very quickly be found by doing too much too soon before your body has adapted to prior loads and before it is ready for greater demands. When you track down the training weeks of top endurance athletes, it may look like they run 160 kilometres (100 miles) a week at phenomenal speeds. But, it is all relative. If your marathon pace is 2:55 per kilometre (4:40 per mile) and you are very much accustomed to running 160 kilometres (100 miles) a week, popping out for a pre-breakfast 16 km (10 mile) run at 3:45 per km (6:00 per mile) is literally no sweat, even though to others that may seem incredibly quick. Do not simply copy what others are doing; it most likely won’t work for you. Instead, learn from the habits of “successful” others. I grew up in the 90s on the London-Surrey border, training at Kingsmeadow track, Richmond Park, and Bushey Park. The pleasure in this upbringing was not being able to rock my socks off whenever Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, or Rage Against the Machine came to London but in that my training locations were where Kenyan athletes used to train during their summer track season. Watching these folks effortlessly tick off eternal 55-second 400-repeats was something my ginger brain found pretty tough to handle. Nonetheless, it was actually watching them on their easy days that really made my ginger hair wither in astonishment. It was common to see them bouncing along around the streets of Teddington at 5 to 6-mins/km (8 to 10-minutes per mile). At the age of 17, this was my first introduction to “go easy on easy days”, a concept that the athletes and coaches surrounding me at the time seemingly misunderstood. Be more Kenyan.

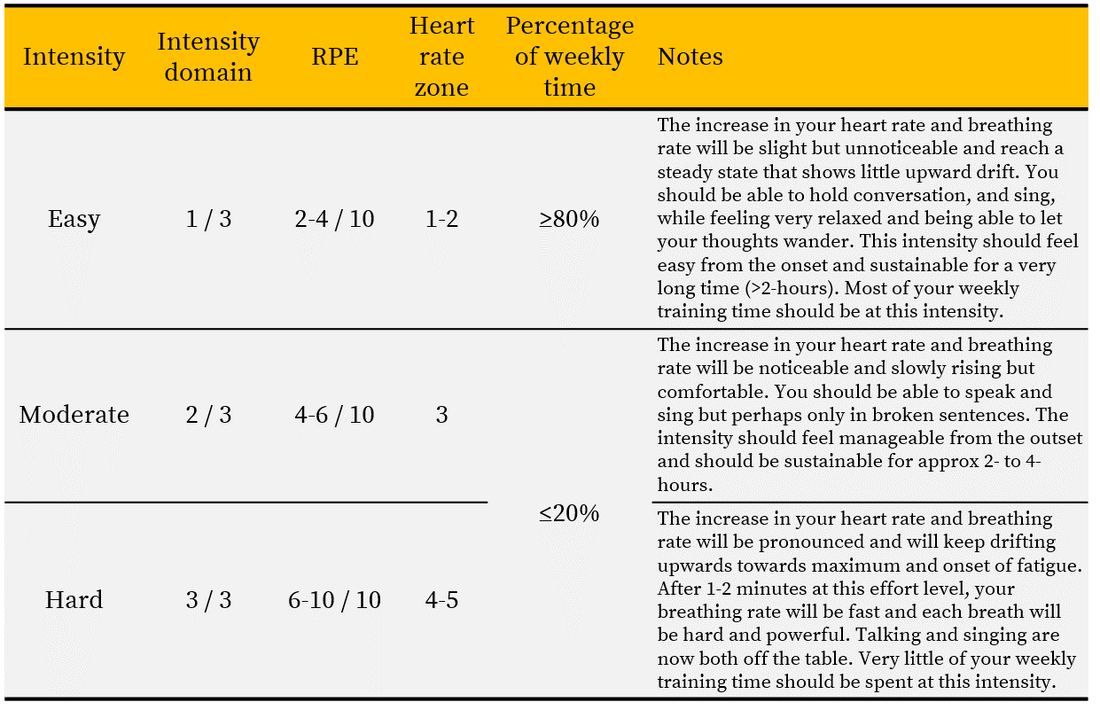

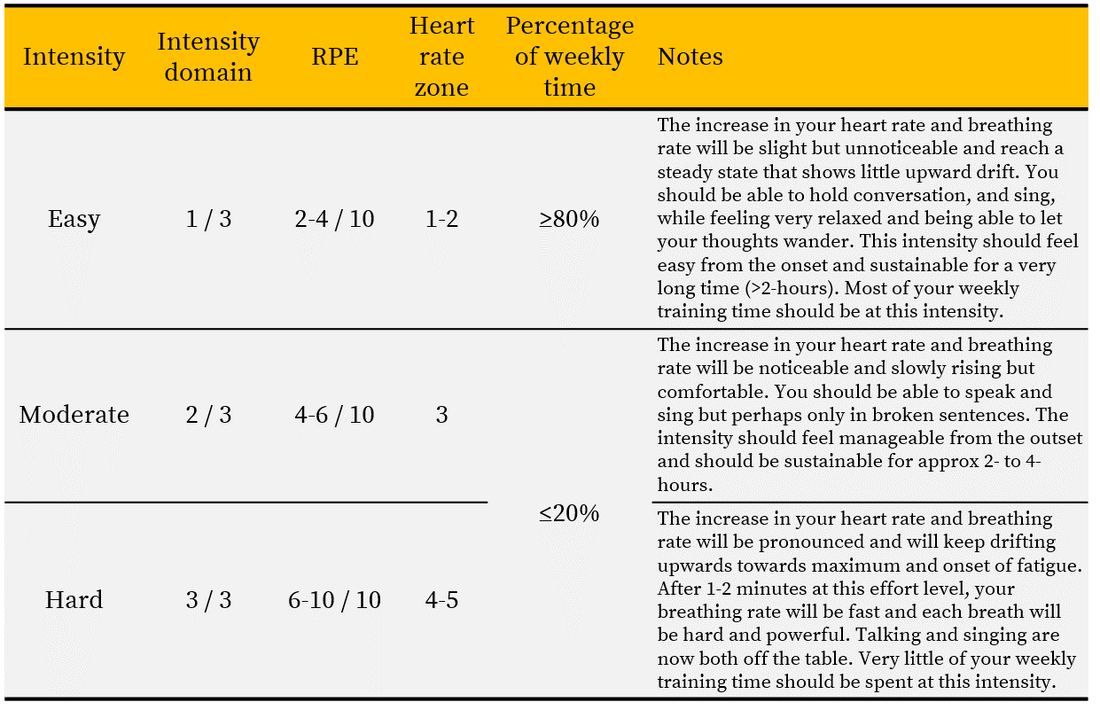

Easy means easy. Rate your maximal perceived exertion (or RPE) during any activity as 10 out of 10. At this rating you are moving rapidly, your heart is pounding, and you are breathing so hard that you do not feel like you have long until you will fatigue. Now, an easy day should rate somewhere between 2 and 4 out of 10. At this level of exertion, the intensity of your work will cause an unnoticeable increase in your heart rate and breathing rate, where you could easily hold a long soliloquy, you could even sing a song without losing your breath. If you measure heart rate, you should not notice any (or very little) upward drift as the workout proceeds, your effort level will elicit a heart rate somewhere in zone 1 or 2. This means moving slowly, really slowly, even on flat terrain. Furthermore, when going up an incline, you will need to step off the gas entirely, likely even slowed to a walk. And that is totally fine because this type of training is building your foundation to handle tougher work. Go slow, take it easy, and invest the majority of your time training “easy”. Boost your training volume with “easy” efforts and easy days, not with additional hard days.

Easy means easy. Rate your maximal perceived exertion (or RPE) during any activity as 10 out of 10. At this rating you are moving rapidly, your heart is pounding, and you are breathing so hard that you do not feel like you have long until you will fatigue. Now, an easy day should rate somewhere between 2 and 4 out of 10. At this level of exertion, the intensity of your work will cause an unnoticeable increase in your heart rate and breathing rate, where you could easily hold a long soliloquy, you could even sing a song without losing your breath. If you measure heart rate, you should not notice any (or very little) upward drift as the workout proceeds, your effort level will elicit a heart rate somewhere in zone 1 or 2. This means moving slowly, really slowly, even on flat terrain. Furthermore, when going up an incline, you will need to step off the gas entirely, likely even slowed to a walk. And that is totally fine because this type of training is building your foundation to handle tougher work. Go slow, take it easy, and invest the majority of your time training “easy”. Boost your training volume with “easy” efforts and easy days, not with additional hard days.

Sprinkling some tougher sessions into your training is sensible, but not every day. Referring back to your rating of perceived exertion, the RPE scale, your Easy workouts should always rate no harder than RPE 4/10. But what RPE should you target during tougher sessions? Well... it depends on the purpose. The table below provides some clues. For a long easy run or a mountain hike, for example, you should aim for 2 to 4 out of 10. During a long, marathon-paced effort, on the other hand, you should aim to start at an RPE of around 4/10, progressing up towards 6 to 8 out of 10 by the end of 1- to 2-hours of running. A threshold run, is a little tougher, during which you should be aiming to run at an RPE of around 8/10; whereas a session of SHIT (short high-intensity training) may be above RPE 8/10 at 9-10 out of 10. Importantly, you should consider that just 1 hard session a week may be sufficient for you; it is for most people. For some folks, two, maybe even three, hard sessions per week can be achieved. But this should not be the goal. Find the frequency that works for you. If you find that only one tough session per week is manageable then stick to that for several weeks. Be patient. The adaptations will come.

Sprinkling some tougher sessions into your training is sensible, but not every day. Referring back to your rating of perceived exertion, the RPE scale, your Easy workouts should always rate no harder than RPE 4/10. But what RPE should you target during tougher sessions? Well... it depends on the purpose. The table below provides some clues. For a long easy run or a mountain hike, for example, you should aim for 2 to 4 out of 10. During a long, marathon-paced effort, on the other hand, you should aim to start at an RPE of around 4/10, progressing up towards 6 to 8 out of 10 by the end of 1- to 2-hours of running. A threshold run, is a little tougher, during which you should be aiming to run at an RPE of around 8/10; whereas a session of SHIT (short high-intensity training) may be above RPE 8/10 at 9-10 out of 10. Importantly, you should consider that just 1 hard session a week may be sufficient for you; it is for most people. For some folks, two, maybe even three, hard sessions per week can be achieved. But this should not be the goal. Find the frequency that works for you. If you find that only one tough session per week is manageable then stick to that for several weeks. Be patient. The adaptations will come.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Keep the stimuli consistent but avoid doing the same exact sessions week-in-week-out. Physical inactivity, i.e. prolonged sitting is the root of many evils, including chronic disease. Even just a few days of inactivity can unfavourably alter body composition and reduce cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max). So, aim to do something every day. It might be a run, it might be a strength workout. It might be a hike, perhaps some non-loading activity (biking, swimming), it might be some mobility or balance exercises, or it may be an R&R day to relax, gently walk, sleep, and recover. Whatever it is, keep your microcycles consistently loaded, aiming to maintain a sensible minimum training dose (i.e. a sensible frequency, intensity, and time) that it is in tune with your current fitness level and that fits in with your life tasks.

Keep the stimuli consistent but avoid doing the same exact sessions week-in-week-out. Physical inactivity, i.e. prolonged sitting is the root of many evils, including chronic disease. Even just a few days of inactivity can unfavourably alter body composition and reduce cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max). So, aim to do something every day. It might be a run, it might be a strength workout. It might be a hike, perhaps some non-loading activity (biking, swimming), it might be some mobility or balance exercises, or it may be an R&R day to relax, gently walk, sleep, and recover. Whatever it is, keep your microcycles consistently loaded, aiming to maintain a sensible minimum training dose (i.e. a sensible frequency, intensity, and time) that it is in tune with your current fitness level and that fits in with your life tasks.

Be consistent with your training but stay calm in the face of adversity. “Use it or lose it” is not just a cliché. Learn to manage your distractions to help your adherence to your plan and to fuel your commitment to consistency. But, if you miss a day, learn to understand that that is totally fine. Each training session provides physical stress. The days you do not train, removes that physical stress. Often a session is missed because of another stress; for example, the psychological stress of an event that was out of your control or physiological stress like an illness or an injury. Don’t try to make up for the missed session by adding more exercise intensity or time the next day, just take the mindset that you are simply on the same roller coaster of stress that all athletes face. The missed day will lessen the physical stress and help you to recover appropriately and adapt accordingly. By “making up for it” when you miss a day, your next physical stress will likely be too large and take too many resources to recover from. So relax and pretend you are taking orders from Stormtroopers in Mos Eisley, “move along, move along”...

Be consistent with your training but stay calm in the face of adversity. “Use it or lose it” is not just a cliché. Learn to manage your distractions to help your adherence to your plan and to fuel your commitment to consistency. But, if you miss a day, learn to understand that that is totally fine. Each training session provides physical stress. The days you do not train, removes that physical stress. Often a session is missed because of another stress; for example, the psychological stress of an event that was out of your control or physiological stress like an illness or an injury. Don’t try to make up for the missed session by adding more exercise intensity or time the next day, just take the mindset that you are simply on the same roller coaster of stress that all athletes face. The missed day will lessen the physical stress and help you to recover appropriately and adapt accordingly. By “making up for it” when you miss a day, your next physical stress will likely be too large and take too many resources to recover from. So relax and pretend you are taking orders from Stormtroopers in Mos Eisley, “move along, move along”...

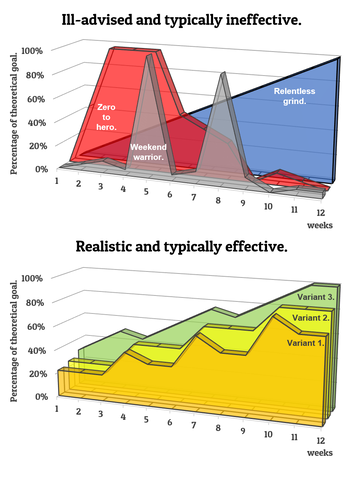

Be consistent with your progression. To help achieve your maximal fitness level, it is sensible to optimise recovery while considering increasing your exercise dose (i.e. your workload). Not every day, not necessarily always every week. But from time to time, do a little bit more. Your training should be designed to provide gradual increases in physical stress over time with daily fluctuations driven by adding and removing different doses of stimuli. Exercise progression may be achieved by adjusting either the frequency, intensity, and/or time, of your running sessions or by adjusting the frequency, resistance, and/or repetitions of your strength sessions, thus progressing the overall exercise dose. There are several models of progression, which I get to in a moment. I have experimented with most of these models in my own training and in clients’ programming. My empirical observations, as well as the published evidence, show the same thing: there is no perfect approach. Whether you choose blocks of phases of 2-, 3-, or 4-weeks, divided into 7-, 10-, or 14-day microcycles, it is indeed possible to cherry-pick someone's training or an article somewhere to say, “yep, that works”. In reality, the importance of making fitness gains is found in progressively-increasing your exercise dose from time to time (primarily through increments in the duration of your “easy” sessions), reducing the dose occasionally, and maintaining some speed work year-round. A major risk factor for soft tissue injury is a rapid increase in exercise dose. So, by making small and gradual increments to your duration, intensity, and/or frequency of your sessions, you may mitigate that risk. The mantra of “start low and go slow” is perfect for helping to avoid crashing and burning through physical and/or mental fatigue, minimising injury risk, and maximising adherence. The increments in stress need to be gradual for the body to optimally adapt.

Be consistent with your progression. To help achieve your maximal fitness level, it is sensible to optimise recovery while considering increasing your exercise dose (i.e. your workload). Not every day, not necessarily always every week. But from time to time, do a little bit more. Your training should be designed to provide gradual increases in physical stress over time with daily fluctuations driven by adding and removing different doses of stimuli. Exercise progression may be achieved by adjusting either the frequency, intensity, and/or time, of your running sessions or by adjusting the frequency, resistance, and/or repetitions of your strength sessions, thus progressing the overall exercise dose. There are several models of progression, which I get to in a moment. I have experimented with most of these models in my own training and in clients’ programming. My empirical observations, as well as the published evidence, show the same thing: there is no perfect approach. Whether you choose blocks of phases of 2-, 3-, or 4-weeks, divided into 7-, 10-, or 14-day microcycles, it is indeed possible to cherry-pick someone's training or an article somewhere to say, “yep, that works”. In reality, the importance of making fitness gains is found in progressively-increasing your exercise dose from time to time (primarily through increments in the duration of your “easy” sessions), reducing the dose occasionally, and maintaining some speed work year-round. A major risk factor for soft tissue injury is a rapid increase in exercise dose. So, by making small and gradual increments to your duration, intensity, and/or frequency of your sessions, you may mitigate that risk. The mantra of “start low and go slow” is perfect for helping to avoid crashing and burning through physical and/or mental fatigue, minimising injury risk, and maximising adherence. The increments in stress need to be gradual for the body to optimally adapt.

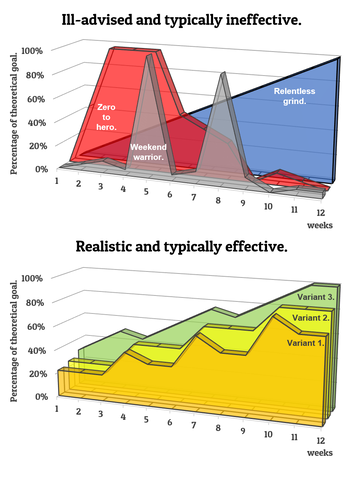

There are several examples of ill-advised and typically ineffective progression models I regularly see people using, that more often than not cause injury, chronic fatigue, mental burn-out, or loss-of-interest. These are shown in the figure below and include the “zero to hero to zero”, where the afflicted crashes straight into high-volume, high-intensity work, to then burn and fall by the wayside.; the “weekend warrior” is a classic where very little physical stress is applied for several weeks with intermittent crash weeks; and the “relentless grind”, which just piles on the volume and intensity week-after-week hoping that nothing falls apart. Anecdotally, I only see these models used by people not too focussed on their fitness gains or by those who spend most of their time “recovering from injury” or simply joining and leaving the competitive scene like a yo-yo. Instead of such foolish approaches, more realistic and effective approaches involve small increments in overall physical stress interspersed with “recovery” weeks where no further increments are made. There are several permutations of a “realistic” progression model, each of which have been shown to be effective by published papers, empirical observations in textbooks. Furthermore, such realistic models are that which the progressions of world-class athletes tend to display. So, aim to be realistic.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

If you do not understand the purpose of a certain session, question it. “What is the purpose of today’s workout?” is a question you should always strive to answer while designing your training. Is it to build endurance, hone speed, bolster strength? Some of the people I have advised/coached are inquisitive and naturally wish to understand the why in their training, while others are silent. Because of the numerous “tasks” of modern daily living that we have conjured up, on a personal level I always need to know why I am doing what I am doing in every aspect of life. This trait helps me characterise and prioritise, and then accept or reject the various tasks and/or requests that are presented to me. This is much to the annoyance of many a teacher/colleague/student in my life, but I prefer efficient living. As an extension of this trait, in relation to training, I need to know the purpose of a session before I am released into the outdoors to “waste” precious time on said session. As a coach, whether an athlete needs or wants clarity, my mind is only clear if I am able to provide or explain the purpose in a particular approach. So, in becoming an architect of your own journey, aim for clarity in the purpose of each session. In doing so, your training design will manifest with simplicity.

If you do not understand the purpose of a certain session, question it. “What is the purpose of today’s workout?” is a question you should always strive to answer while designing your training. Is it to build endurance, hone speed, bolster strength? Some of the people I have advised/coached are inquisitive and naturally wish to understand the why in their training, while others are silent. Because of the numerous “tasks” of modern daily living that we have conjured up, on a personal level I always need to know why I am doing what I am doing in every aspect of life. This trait helps me characterise and prioritise, and then accept or reject the various tasks and/or requests that are presented to me. This is much to the annoyance of many a teacher/colleague/student in my life, but I prefer efficient living. As an extension of this trait, in relation to training, I need to know the purpose of a session before I am released into the outdoors to “waste” precious time on said session. As a coach, whether an athlete needs or wants clarity, my mind is only clear if I am able to provide or explain the purpose in a particular approach. So, in becoming an architect of your own journey, aim for clarity in the purpose of each session. In doing so, your training design will manifest with simplicity.

Take your legs for a test-drive once in a while. After progressing the dose of his activity for a few months, once again Forrest Gump proved he was a genius. What did he do? Yep, he tested his new legs out and ran as fast as he could (very smart)... against a speeding car (less smart; not recommended). Having a goal to aim towards will help motivate you to keep up your new habits. So, after several weeks to allow adaptations, try out your “new legs” and build test-drives into your design. It is fun to track how your fitness is changing. Find a local race, a park run, or run a self-timed time-trial on your local running track. Maybe your peak sprint velocity has increased? Has your sustained pace at a particular RPE increased? Has your heart rate at a particular pace decreased? Has your 1RM increased on a particular lift? Can you hang on a bar for longer? Can you do more unbroken pull-ups than ever before? You do not have to answer yes to all these questions every time they are tested, but the general trend in your fitness with time should be an increasing one. To help monitor that, aim to incorporate “test-drives” into your schedule...

Take your legs for a test-drive once in a while. After progressing the dose of his activity for a few months, once again Forrest Gump proved he was a genius. What did he do? Yep, he tested his new legs out and ran as fast as he could (very smart)... against a speeding car (less smart; not recommended). Having a goal to aim towards will help motivate you to keep up your new habits. So, after several weeks to allow adaptations, try out your “new legs” and build test-drives into your design. It is fun to track how your fitness is changing. Find a local race, a park run, or run a self-timed time-trial on your local running track. Maybe your peak sprint velocity has increased? Has your sustained pace at a particular RPE increased? Has your heart rate at a particular pace decreased? Has your 1RM increased on a particular lift? Can you hang on a bar for longer? Can you do more unbroken pull-ups than ever before? You do not have to answer yes to all these questions every time they are tested, but the general trend in your fitness with time should be an increasing one. To help monitor that, aim to incorporate “test-drives” into your schedule...

Thus concludes Part 2 on your three-part journey. Having now learned how to plan and design, go ahead and get started using the FITT-PR framework:

Thanks for joining me on this second part of your architectural training journey. Complete your training in the final review phase of the journey.

Until next time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be by training smart...

To continue your architecture education, here in Part 2 I will delve into how you might optimise your training design. The purpose of this article is not to tell you how many times a week to train, how many kilometres to run, or how much weight to lift since those variables are unique to you. Instead, my aim is to arm you with additional tools with which to become knowledgeable in safe and effective design.

Part 2: Design your training.

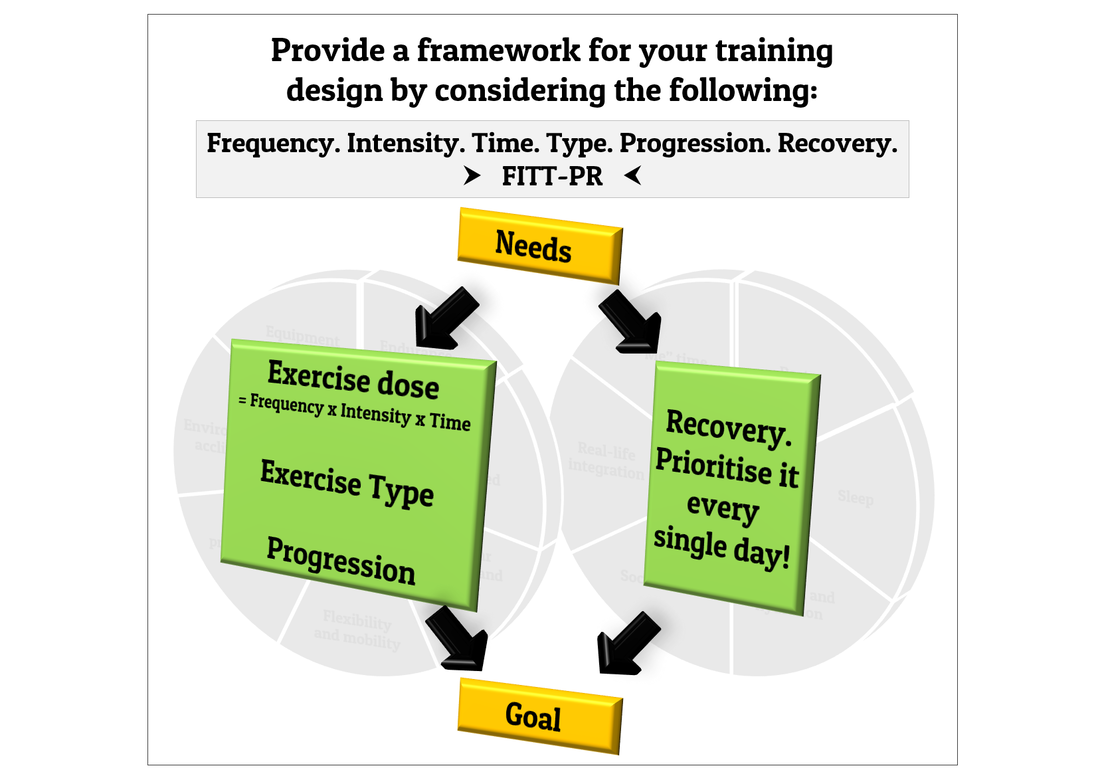

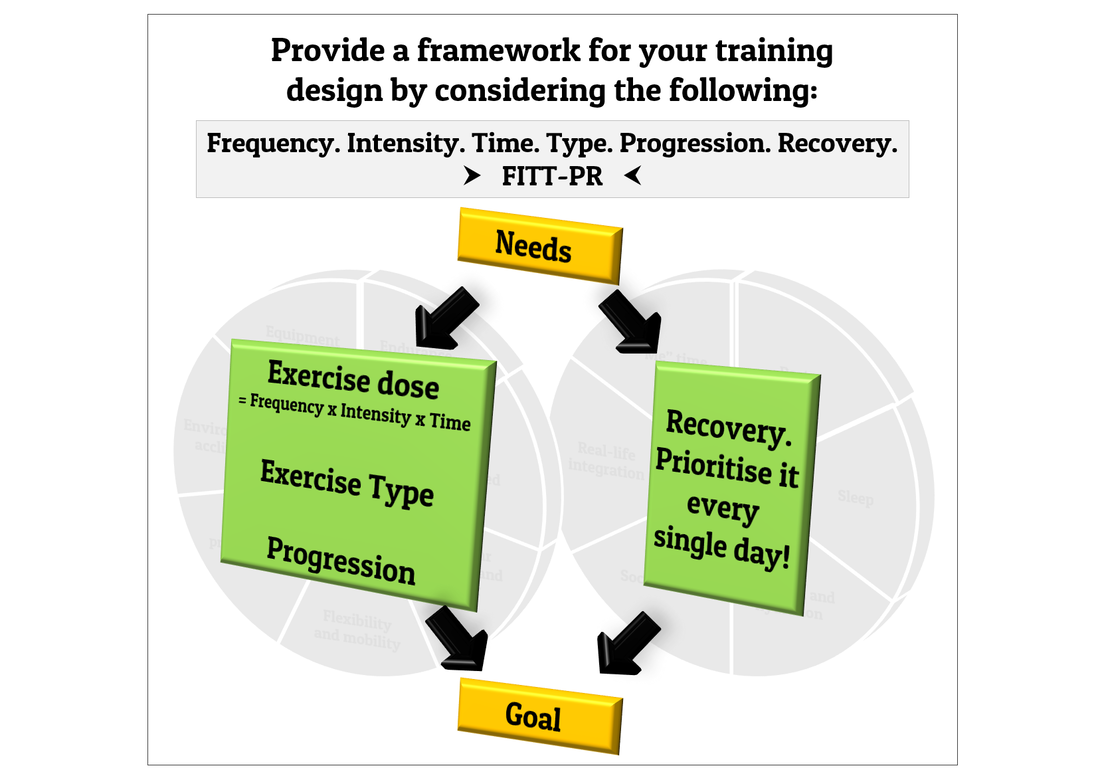

To appropriately build your training using the ingredients of the original training pie, you may now consider those ingredients using a simple framework. Thus, having already identified your SMART goal and having already made a needs analysis, some clarity will emerge as to how you might design your training. As shown in the diagram below, you should think about the dose of exercise you will start with, which is a function of frequency, intensity, and time; you should also contemplate the type of exercise you will use, for example aerobic, strength, flexibility sessions etc; and you should ponder how you will progress the dose of the different types of exercise. Furthermore, to maximise the chance of optimally adapting to the physical stress you will impose on yourself, also strive to prioritise the ingredients of “Recovery” every single day. To keep things simple and help materialise the clarity in your design, you may consider using the simple mantra of Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type, Progression, and Recovery (FITT-PR) as a framework.

×

![]()

Understanding this framework in the context of your needs and goal will help maximise success. But, like I said last time, it is my observation that the training design frequently goes wrong. To help understand how to mitigate the common occurrence of heading off piste with your training design, please read on:

×

![]()

There are several examples of ill-advised and typically ineffective progression models I regularly see people using, that more often than not cause injury, chronic fatigue, mental burn-out, or loss-of-interest. These are shown in the figure below and include the “zero to hero to zero”, where the afflicted crashes straight into high-volume, high-intensity work, to then burn and fall by the wayside.; the “weekend warrior” is a classic where very little physical stress is applied for several weeks with intermittent crash weeks; and the “relentless grind”, which just piles on the volume and intensity week-after-week hoping that nothing falls apart. Anecdotally, I only see these models used by people not too focussed on their fitness gains or by those who spend most of their time “recovering from injury” or simply joining and leaving the competitive scene like a yo-yo. Instead of such foolish approaches, more realistic and effective approaches involve small increments in overall physical stress interspersed with “recovery” weeks where no further increments are made. There are several permutations of a “realistic” progression model, each of which have been shown to be effective by published papers, empirical observations in textbooks. Furthermore, such realistic models are that which the progressions of world-class athletes tend to display. So, aim to be realistic.

×

![]()

But how much and how far should you progress? There is no hard and fast rule on the approach. As for how far you can progress, you will learn what you can handle on your own journey. As for how much you should progress… Yes, you have heard of the 10% rule of weekly mileage increments for minimising injury risk. I, for one, cannot trace the origin of this “rule”. It may work for you, it may not. Published data do not support 10% increments as a “rule” per se. And, if you do some simple calculations of 10% increments from a range of starting points, you will immediately see its limitations. My advice: focus on consistency, be sensible, learn to understand yourself, and only increase when you feel ready. By learning to understand your body; you will know when you are ready. Furthermore, by planning recovery sessions and recovery and/or rest days within your week while integrating recovery weeks within your training cycles, you will further help to maximise your adaptations while mitigating risks. Remember, your fitness increases in between exercise sessions not during them. So, the higher you raise your exercise dose, the more important recovery becomes. Yes, ultra-legend speed demon Jim Walmsley can handle 200-kilometre weeks; at the moment, you probably cannot.

Thus concludes Part 2 on your three-part journey. Having now learned how to plan and design, go ahead and get started using the FITT-PR framework:

Frequency. Intensity. Time. Type. Progression. Recovery.

Until next time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be by training smart...

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Driftline and Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.