Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — What causes cramps?

→ Part 2 — How to prevent & treat cramps.

→ Part 1 — What causes cramps?

→ Part 2 — How to prevent & treat cramps.

Muscle cramps. Part 2 of 2:

How to stop muscle cramps during training and racing.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

11th Dec 2021.

In the first part of this series, I introduced you to the phenomenon of sudden involuntary muscle contractions, aka cramping... a runner’s nightmare. In this second part, I dig into what you really care about — how to stop the Krampus monster.

Reading time ~16-mins.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

To pick up where we left off and build a foundation for strategies for preventing and treating cramps, we must ask a simple question...

Dehydration — loss of body water and sodium.

Dehydration — loss of body water and sodium.

Hypoglycemia — low blood glucose.

Hypoglycemia — low blood glucose.

Glycogen depletion — low fuel stores.

Glycogen depletion — low fuel stores.

Metabolic acidosis — hydrogen ion accumulation.

Metabolic acidosis — hydrogen ion accumulation.

Hyperthermia — high core temperature.

Hyperthermia — high core temperature.

Hypothermia — low core temperature.

Hypothermia — low core temperature.

Muscle damage and neuromuscular dysfunction, and so on…

Muscle damage and neuromuscular dysfunction, and so on…

Given this complexity, it isn’t possible to assign your (poor) body water and electrolyte balance as the sole cause of your (failed) performance. Yet, we fall foul to our cognitive biases and use mental shortcuts to jump to what is available — “I have had cramps before, so it must be common.” and “I’ve heard cramping is related to salt so I must be dehydrated and needing sodium”.

Yes, if you hadn’t drunk any water for hours before a race, had been sweating balls, and were thirsty on the start line, then a cramp-induced poor race performance might be attributable to dehydration, especially if it was hot. If you had been guzzling large amounts of water or low-sodium sports drinks while sweating a lot in the heat, then yes, you might blame sodium depletion as the cause of your cramp. But, if you started euhydrated and drank-to-thirst during the race, dehydration and/or sodium loss are far less likely to be the culprit.

On EVERY occasion I have finished a race and heard my competitors clamour, “Man, i needed salt today, my cramps were so bad”, we had just finished a race that was either far further or far more technical and mountainous than any of us were familiar with or prepared for. Personally, on all 4 occasions, I have suffered cramps during a race, I was way out of my depth. Two examples: racing over 3000 metres of elevation gain off-trail in Norway when to that point I had only ever done ~1000m in a single run. And, carrying 2 × 60 lb (2 × 27 kg) sandbags up a ski slope in the closing kms of a 2-hour race in the mountains. In those scenarios, my brain immediately diagnosed the problem as “By the beard of Zeus, I was not conditioned for that.”. Yet, on both those occasions, it was also hot. And, on one of the occasions, there were no opportunities for cooling, drinking, or eating en route.

Did I jump to conclusions?

Maybe.

But, what about the hundreds of other times I’ve raced/trained in the heat without access to fluid and did not get any cramps? Oh how difficult you are to understand.

The other problem is that it is impossible to immediately study cramping in an athlete during a race. We have no choice but to use retrospective designs that backtrack and try to unravel what factors predict the cramping or to use prospective study designs using methods that “mimic” what might happen during exercise. For example, exercise-associated muscle cramps can be induced in the lab using a sustained voluntary contraction with muscles held at a short length. But this does not mimic what happens during a race. Alternatively, cramps can be induced using electrical nerve stimulation. Doing so, allows us to find the lowest nerve stimulation frequency that causes cramping — the threshold frequency — and to see how much this changes under various conditions (dehydration, fatigue, etc). Interestingly, the threshold frequency is often lower in folks with a history of cramping. But, once again, this does not reflect the real-world athlete race setting because it only reveals the susceptibility to cramps and cannot unravel what caused your cramping on race day.

My point is that cramps are notoriously difficult to study in an ecologically-meaningful way. Consequently, it is near-impossible to know the cause of your cramping when it happens during a session or race and, therefore, it is near-impossible to specify a prevention and/or treatment strategy that will work every time. Cramping is like chasing a rainbow. Fortunately, this rainbow has some arcs of colourful clarity:

Cramps most often occur when you are fatigued, so you need a strategy that helps you resist fatigue for longer.

Cramps most often occur when you are fatigued, so you need a strategy that helps you resist fatigue for longer.

Cramps are more likely when muscle damage has occured, so you need a strategy that makes you more durable.

Cramps are more likely when muscle damage has occured, so you need a strategy that makes you more durable.

Cramps are more likely when it is hot, so you need a strategy that keeps you cool.

Cramps are more likely when it is hot, so you need a strategy that keeps you cool.

Cramps are more likely when you are dehydrated, so you need a strategy that keeps you hydrated.

Cramps are more likely when you are dehydrated, so you need a strategy that keeps you hydrated.

Since you might associate thirst, hydration, and salt with your cramps while ignoring your state of fatigue, muscle damage, and race day temperature, these knowns provide some clues as to the thing you are probably most interested in…

If your current prevention and treatment approaches are based on a combination of a lack of knowledge, personal experience, anecdotes, and belief in a particular method, consider adding an evidence-informed preventative approach to your practice…

Start by thinking:

Sleep — A lack of sleep impairs neuromuscular function and reduces endurance and strength performance. Ensuring adequate sleep prior to a race may help you resist fatigue and lower your risk of cramping. So, educate yourself in the art of sleep hygiene.

Sleep — A lack of sleep impairs neuromuscular function and reduces endurance and strength performance. Ensuring adequate sleep prior to a race may help you resist fatigue and lower your risk of cramping. So, educate yourself in the art of sleep hygiene.

Training — Cramping is essentially your brain saying “Yeah, but nah”. If you consider cramps this way, you will realise that you must prepare your body for the imposed demands of race day by exposing your brain to the intensity, duration, and technicality of the event during your training build-up. I have found it very common for athletes accustomed to flat level non-technical running, to suffer cramps when racing on highly-technical (uneven/lumpy/rocky/boggy) and mountainous terrain, which includes a vicious mix of energy-demanding climbing and cognitively-demanding and muscle-damaging descending. I have also found it common for athletes with low volume training or low volume long runs to experience cramps during long-duration races. Interestingly, the 2020 study of marathon runners that found greater muscle damage in crampers vs. non-crampers also found that runners who included strength conditioning in their training were less likely to suffer cramping during their marathons. If you have no idea how to train for the demands of your event, then you need to educate yourself in the architecture of your training (planning, designing, and reviewing) and training load management because you need to be durable to minimise muscle damage and to resist fatigue for as long as possible.

Training — Cramping is essentially your brain saying “Yeah, but nah”. If you consider cramps this way, you will realise that you must prepare your body for the imposed demands of race day by exposing your brain to the intensity, duration, and technicality of the event during your training build-up. I have found it very common for athletes accustomed to flat level non-technical running, to suffer cramps when racing on highly-technical (uneven/lumpy/rocky/boggy) and mountainous terrain, which includes a vicious mix of energy-demanding climbing and cognitively-demanding and muscle-damaging descending. I have also found it common for athletes with low volume training or low volume long runs to experience cramps during long-duration races. Interestingly, the 2020 study of marathon runners that found greater muscle damage in crampers vs. non-crampers also found that runners who included strength conditioning in their training were less likely to suffer cramping during their marathons. If you have no idea how to train for the demands of your event, then you need to educate yourself in the architecture of your training (planning, designing, and reviewing) and training load management because you need to be durable to minimise muscle damage and to resist fatigue for as long as possible.

Resting — As I discussed in Part 1, an insufficient taper and pre-race muscle damage increase the risk of cramping. But, in addition to physical fatigue, cognitively demanding tasks (aka mental fatigue) also impair neuromuscular function and reduce endurance and strength performance. So, ensuring adequate physical and mental rest before a race may help scare the Krampus monster away.

Resting — As I discussed in Part 1, an insufficient taper and pre-race muscle damage increase the risk of cramping. But, in addition to physical fatigue, cognitively demanding tasks (aka mental fatigue) also impair neuromuscular function and reduce endurance and strength performance. So, ensuring adequate physical and mental rest before a race may help scare the Krampus monster away.

Eating — Glycogen depletion causes fatigue. Fatigue causes cramps. If you have no idea how to establish and maintain high carbohydrate availability during your sessions and races to help resist fatigue, then you need to educate yourself in the art of performance nutrition.

Eating — Glycogen depletion causes fatigue. Fatigue causes cramps. If you have no idea how to establish and maintain high carbohydrate availability during your sessions and races to help resist fatigue, then you need to educate yourself in the art of performance nutrition.

Travelling — To echo what I just said, cognitively demanding tasks (aka mental fatigue) impair neuromuscular function and reduce endurance and strength performance. I.e. mental fatigue causes muscle fatigue. Driving or flying for a million hours to your race is cognitively demanding. Consider travelling to your “A races” well ahead of time so you can recover from the travel, acclimate to the new environment, locate food, and rest, and sleep. Yes, this might sound expensive but why are you diverting so much of your time towards training if you aren’t willing to focus time on nailing race day?

Travelling — To echo what I just said, cognitively demanding tasks (aka mental fatigue) impair neuromuscular function and reduce endurance and strength performance. I.e. mental fatigue causes muscle fatigue. Driving or flying for a million hours to your race is cognitively demanding. Consider travelling to your “A races” well ahead of time so you can recover from the travel, acclimate to the new environment, locate food, and rest, and sleep. Yes, this might sound expensive but why are you diverting so much of your time towards training if you aren’t willing to focus time on nailing race day?

Cooling — Overheating causes fatigue. Being cold causes fatigue. Fatigue causes cramps. If it is hot and you have no idea how to stay cool during your sessions and races, then you need to educate yourself in pre- and during-exercise cooling methods and heat acclimation strategies. Similarly, if it is cold, educate yourself how to stay warm and cold acclimation strategies.

Cooling — Overheating causes fatigue. Being cold causes fatigue. Fatigue causes cramps. If it is hot and you have no idea how to stay cool during your sessions and races, then you need to educate yourself in pre- and during-exercise cooling methods and heat acclimation strategies. Similarly, if it is cold, educate yourself how to stay warm and cold acclimation strategies.

Hydrating — In extreme circumstances — in the heat — cramping can be triggered by dehydration, sodium depletion. But guzzling large unnecessary volumes of water can dilute plasma sodium. And, remember, most “standard” sports drinks are low in sodium and drinking large volumes when you are sweating a lot will further dilute plasma sodium (see Table of drinks here). If you have no idea what hydration is and/or no clue when dehydration and sodium depletion do and do not affect performance, then you need to educate yourself in the art of hydration.

Hydrating — In extreme circumstances — in the heat — cramping can be triggered by dehydration, sodium depletion. But guzzling large unnecessary volumes of water can dilute plasma sodium. And, remember, most “standard” sports drinks are low in sodium and drinking large volumes when you are sweating a lot will further dilute plasma sodium (see Table of drinks here). If you have no idea what hydration is and/or no clue when dehydration and sodium depletion do and do not affect performance, then you need to educate yourself in the art of hydration.

A 2021 narrative review by world experts in the prevention of cramps, concluded by saying: “Individualizing EAMC [exercise-associated muscle cramps] prevention strategies will likely be more effective than generalized advice (e.g., drink more fluids).”. While there is an emerging preventative approach called “cramp training”, where repeated exposure to electrically-induced cramps has been shown to reduce cramp susceptibility, this has only been demonstrated in one study and we must await more evidence. In the meantime, if you are cramp-prone, the previously mentioned S.T.R.E.T.C.H. framework is an essential checklist! If you are not cramp-prone but an athlete trying to be the best you can be, you should be doing these things anyway.

Now you are armed with preemptive prevention strategies. But, what if Krampus attacks during your race...

So, when the cramp monster attacks, what can you do? Provide sympathy or, in the case of Lebron James, start an onslaught of “LeBroning” memes and publish completely uninformative “how to avoid cramps” articles? Or, do your homework…

An internet search will reveal a cauldron full of wonderful cramp-treating pills, potions, and “violent” tasting shots, including magnesium, sodium, vitamins, quinine, pickle juice, mustard, vinegar, capsaicin, ginger, and so on… The list is diverse, which means they cannot tackle the same cause. And, much of that list has not been studied, except through anecdotes. So, let’s look at what we do know...

When the cramping brings you down, your options are simple:

Stop — you probably have no choice but to stop and wait. Cramping often equals pain. Stopping and resting is sometimes all it needs. And, since you are stopped, you might as well be proactive. So...

Stop — you probably have no choice but to stop and wait. Cramping often equals pain. Stopping and resting is sometimes all it needs. And, since you are stopped, you might as well be proactive. So...

Orally hydrate — As you learned in Part 1, we’ve known since the 1930s that drinking salt water, not water alone, reduces the risk of muscle cramps while working hard in the heat. Studies in runners have confirmed that susceptibility to (electrically-induced) calf muscle cramping in the heat is reduced when an electrolyte and glucose-containing solution is drunk during 40 to 60-mins of downhill running, and that drinking water alone worsens cramping susceptibility when dehydrated. These findings emphasise that, when dehydration occurs during exercise in the heat, consuming electrolytes and glucose is a better option than water alone for keeping the Krampus monster at bay.

Orally hydrate — As you learned in Part 1, we’ve known since the 1930s that drinking salt water, not water alone, reduces the risk of muscle cramps while working hard in the heat. Studies in runners have confirmed that susceptibility to (electrically-induced) calf muscle cramping in the heat is reduced when an electrolyte and glucose-containing solution is drunk during 40 to 60-mins of downhill running, and that drinking water alone worsens cramping susceptibility when dehydrated. These findings emphasise that, when dehydration occurs during exercise in the heat, consuming electrolytes and glucose is a better option than water alone for keeping the Krampus monster at bay.

Stretch — In the “cramping soccer player” scenario, you probably also recall a coach slowly pushing the affected player’s straightened leg towards their face — the classic post-sniper hammy stretch. While systematic reviews find no utility of a regular muscle stretching regimen for preventing cramps, stretching the affected area does relieve muscle cramps, sometimes, and is the current gold standard treatment. In the 1957 paper I discussed in Part 1 that induced muscle cramps in college students with prolonged maximal bicep contractions in a shortened position, the authors wrote that “stretching of the affected muscles was an effective way of abolishing most cramps”. Remarkably, however, almost no studies have examined the effect of stretching as an immediate treatment for cramping during exercise. A study in 1993 by Bertolasi et al. found that stretching alleviated cramps induced by voluntary contraction or electrical stimulation but a 2017 study by Panza et al. showed static stretching did not change the susceptibility to electrical-stimulation-induced cramps. In the field, stretching is the go-to and just seems to work, sometimes.

Stretch — In the “cramping soccer player” scenario, you probably also recall a coach slowly pushing the affected player’s straightened leg towards their face — the classic post-sniper hammy stretch. While systematic reviews find no utility of a regular muscle stretching regimen for preventing cramps, stretching the affected area does relieve muscle cramps, sometimes, and is the current gold standard treatment. In the 1957 paper I discussed in Part 1 that induced muscle cramps in college students with prolonged maximal bicep contractions in a shortened position, the authors wrote that “stretching of the affected muscles was an effective way of abolishing most cramps”. Remarkably, however, almost no studies have examined the effect of stretching as an immediate treatment for cramping during exercise. A study in 1993 by Bertolasi et al. found that stretching alleviated cramps induced by voluntary contraction or electrical stimulation but a 2017 study by Panza et al. showed static stretching did not change the susceptibility to electrical-stimulation-induced cramps. In the field, stretching is the go-to and just seems to work, sometimes.

However, there is a major problem…

The simple act of stopping, orally hydrating and stretching — S.O.S. — sounds nice and easy but it does not work for everyone and it does not work every time. Plus, if there is muscle damage, which is quite likely during a long, hard, and technical race, stretching a muscle may further exacerbate the problem by further damaging the tissue.

So, what else can you consider?

Of all the many pills and potions advertised on the internet, the experimental evidence is currently not convincing. For example, systematic reviews of the evidence do not support the use of quinine or magnesium for preventing or treating cramps. For other pills and potions, you will always find enticing anecdotes — some approaches may work sometimes for some athletes — but it doesn’t mean they will work for you. That said, having “belief” in an approach and the placebo effect can be a wonderful thing. But, there is no guarantee that the placebo effect is consistent — it is very likely that what worked for you once won’t work again in a different context. Nonetheless, if it is safe, legal and will not hinder performance, it is probably worth a shot to see whether it might help.

One biological mechanism with treatment potential being exploited by companies like HotShot and CrampFix, is transient receptor potential (TRP) channel agonists.

Say what?!

TRP channel agonists is a mouthful of hot and spicy jargon. In fact, that’s exactly what it is. TRP channel agonists being used for treating muscle cramps are hot and spicy foods, which activate receptors (called TRP channels) in your mouth and/or nasal cavity that trigger nerve impulses. These “shock” therapies taste pretty violent — they contain things like mustard, vinegar, ginger, capsaicin, etc. As you can tell, they don’t taste marvelous. What they do is not entirely clear. But, some work has shown such things to alleviate prolonged-contraction-induced cramping while other studies have found no effect on electrically-induced cramps.

There’s not a mass of data and such products have not been well studied, yet. They might help some people go “Yeah but nah... but yeaaah.”. If you want to try them, firstly make sure the product has been independently tested in the name of “clean sport”. Then, make sure you try the product during a long arduous session because you do not want to wait until race day to discover that it tastes like a shot of shit and makes you wanna emulate a veritable fountain of puke. But, the most important thing to consider if you are a regular cramper, is that no matter how sexy a transient receptor potential channel agonist sounds, a “shock” therapy won’t address the underlying cause of the cramping; it will simply mask the issue. So, I always recommend my athletes to start by picking the low hanging fruit:

Always optimise your training load, nutrition, sleep, and rest before reaching for pills, potions, and devices...

Always optimise your training load, nutrition, sleep, and rest before reaching for pills, potions, and devices...

During a race or session, your goal is to finish. You want to avoid having to abort mission. Stopping, resting, and stretching means you lose time during a race. But, if they allow you to continue, they will minimise your losses and may prevent a DNF. Meanwhile, hydrating with some high sodium drink or “getting weird” with a TRP channel agonist means you might not have to stop at all and might not lose any time... if they work. As I said, cramp is complicated and you have to work out what works for you.

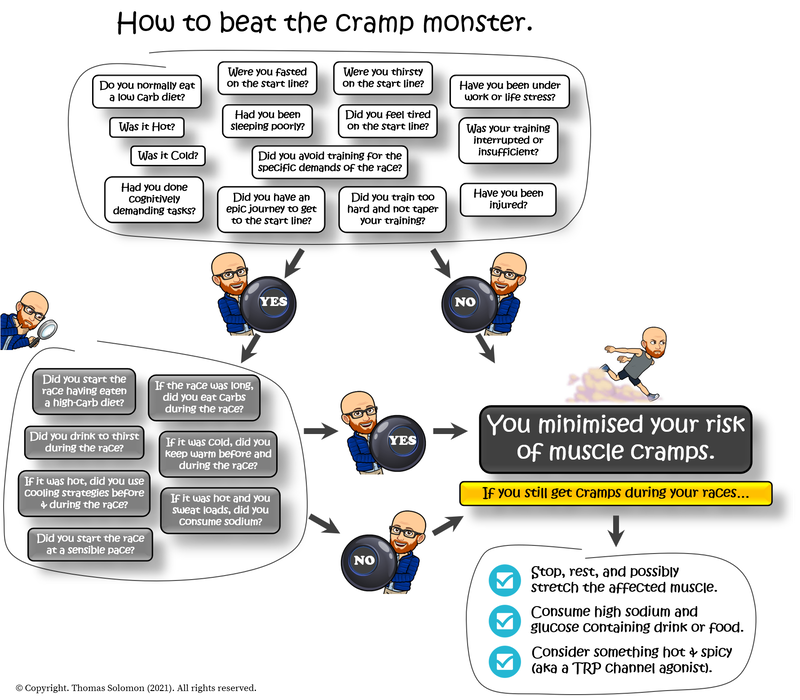

Did you sleep well in the days leading into the race?

Did you sleep well in the days leading into the race?

Had you been well-rested and avoiding cognitively-demanding tasks?

Had you been well-rested and avoiding cognitively-demanding tasks?

Did you taper your training into the race?

Did you taper your training into the race?

Did you have an epic journey to get to the start of the race?

Did you have an epic journey to get to the start of the race?

Did you start the race adequately hydrated? Or... Were you thirsty on the start line?

Did you start the race adequately hydrated? Or... Were you thirsty on the start line?

Did you start the race with high carbohydrate availability?

Did you start the race with high carbohydrate availability?

Did you maintain high carb availability during the race?

Did you maintain high carb availability during the race?

If it was hot, did you keep cool before and during the race? Or… If it was cold, did you keep warm before and during the race?

If it was hot, did you keep cool before and during the race? Or… If it was cold, did you keep warm before and during the race?

If it was hot, did you guzzle large volumes of water or low-sodium sports drinks?

If it was hot, did you guzzle large volumes of water or low-sodium sports drinks?

And, most importantly,

Had your training prepared you for the duration, intensity, and technicality of the race?

Had your training prepared you for the duration, intensity, and technicality of the race?

And/or,

During the race, did you push far too hard, far too soon and start to fade?

During the race, did you push far too hard, far too soon and start to fade?

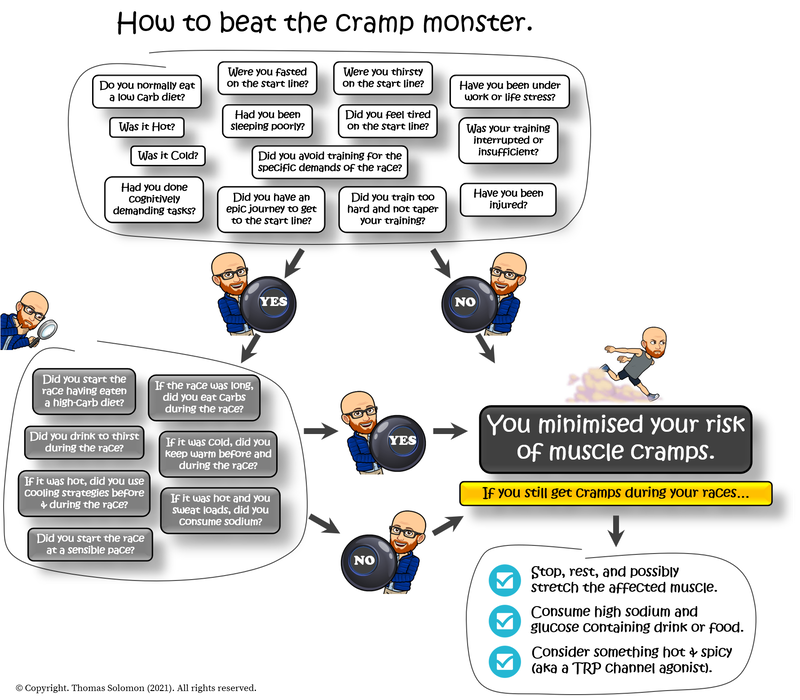

Now, to preemptively minimise your risk of cramping, use this framework:

Train to meet the imposed demands (duration, intensity, & technicality) of your event.

Train to meet the imposed demands (duration, intensity, & technicality) of your event.

Leading into your race, minimise muscle fatigue and damage by tapering your training.

Leading into your race, minimise muscle fatigue and damage by tapering your training.

Leading into your race, minimise mental fatigue by resting and sleeping lots and avoiding stressful environments and cognitively-demanding tasks.

Leading into your race, minimise mental fatigue by resting and sleeping lots and avoiding stressful environments and cognitively-demanding tasks.

If you have to travel far, travel ahead of time (e.g. the day before) to allow mental fatigue to subside and to familiarise to the new environment.

If you have to travel far, travel ahead of time (e.g. the day before) to allow mental fatigue to subside and to familiarise to the new environment.

Always start a race adequately hydrated.

Always start a race adequately hydrated.

During the race, drink to thirst. If the race is long, you typically sweat a lot, and it is hot, consider using sodium.

During the race, drink to thirst. If the race is long, you typically sweat a lot, and it is hot, consider using sodium.

Start every race with high carbohydrate availability (glycogen load).

Start every race with high carbohydrate availability (glycogen load).

If the race is long, eat calories to maintain high carbohydrate availability during the race.

If the race is long, eat calories to maintain high carbohydrate availability during the race.

If it's hot, keep cool before and during the race, and consider a heat acclimation strategy.

If it's hot, keep cool before and during the race, and consider a heat acclimation strategy.

If it's cold, keep warm before and during the race, and consider a cold acclimation strategy.

If it's cold, keep warm before and during the race, and consider a cold acclimation strategy.

If it's high, consider an altitude acclimation strategy.

If it's high, consider an altitude acclimation strategy.

If the cramp monster attacks during the race, stop, stretch, and consume some glucose- and high-sodium-containing food/beverage.

If the cramp monster attacks during the race, stop, stretch, and consume some glucose- and high-sodium-containing food/beverage.

If all else fails, consider a “shock” therapy during the race (strong-tasting TRP receptor agonist products that contain spices like mustard, chilli, capsaicin, etc) but test its palatability during training and ensure it is safe, legal, and will not hinder your performance.

If all else fails, consider a “shock” therapy during the race (strong-tasting TRP receptor agonist products that contain spices like mustard, chilli, capsaicin, etc) but test its palatability during training and ensure it is safe, legal, and will not hinder your performance.

However… Because Krampus is a mysteriously unpredictable beast, and because there is no single cause for every occurence of cramping, and because prevention and treatment strategies are not consistently effective, you must...

Use whatever works for you.

Use whatever works for you.

But be aware that it might not work next time.

But be aware that it might not work next time.

And,

If it works for you, don’t force it on others; it might not work for them.

If it works for you, don’t force it on others; it might not work for them.

Until next time, stay nerdy and keep empowering yourself to be the best athlete you can be, by training smart…

Why are exercise-associated muscle cramps so difficult to understand?

The problem is complex because, during long arduous sessions and races, many factors are smashing your body’s homeostasis and causing fatigue:

Yes, if you hadn’t drunk any water for hours before a race, had been sweating balls, and were thirsty on the start line, then a cramp-induced poor race performance might be attributable to dehydration, especially if it was hot. If you had been guzzling large amounts of water or low-sodium sports drinks while sweating a lot in the heat, then yes, you might blame sodium depletion as the cause of your cramp. But, if you started euhydrated and drank-to-thirst during the race, dehydration and/or sodium loss are far less likely to be the culprit.

On EVERY occasion I have finished a race and heard my competitors clamour, “Man, i needed salt today, my cramps were so bad”, we had just finished a race that was either far further or far more technical and mountainous than any of us were familiar with or prepared for. Personally, on all 4 occasions, I have suffered cramps during a race, I was way out of my depth. Two examples: racing over 3000 metres of elevation gain off-trail in Norway when to that point I had only ever done ~1000m in a single run. And, carrying 2 × 60 lb (2 × 27 kg) sandbags up a ski slope in the closing kms of a 2-hour race in the mountains. In those scenarios, my brain immediately diagnosed the problem as “By the beard of Zeus, I was not conditioned for that.”. Yet, on both those occasions, it was also hot. And, on one of the occasions, there were no opportunities for cooling, drinking, or eating en route.

Did I jump to conclusions?

Maybe.

But, what about the hundreds of other times I’ve raced/trained in the heat without access to fluid and did not get any cramps? Oh how difficult you are to understand.

The other problem is that it is impossible to immediately study cramping in an athlete during a race. We have no choice but to use retrospective designs that backtrack and try to unravel what factors predict the cramping or to use prospective study designs using methods that “mimic” what might happen during exercise. For example, exercise-associated muscle cramps can be induced in the lab using a sustained voluntary contraction with muscles held at a short length. But this does not mimic what happens during a race. Alternatively, cramps can be induced using electrical nerve stimulation. Doing so, allows us to find the lowest nerve stimulation frequency that causes cramping — the threshold frequency — and to see how much this changes under various conditions (dehydration, fatigue, etc). Interestingly, the threshold frequency is often lower in folks with a history of cramping. But, once again, this does not reflect the real-world athlete race setting because it only reveals the susceptibility to cramps and cannot unravel what caused your cramping on race day.

My point is that cramps are notoriously difficult to study in an ecologically-meaningful way. Consequently, it is near-impossible to know the cause of your cramping when it happens during a session or race and, therefore, it is near-impossible to specify a prevention and/or treatment strategy that will work every time. Cramping is like chasing a rainbow. Fortunately, this rainbow has some arcs of colourful clarity:

How can you prevent cramps during running?

Exercise-associated muscle cramps — sudden involuntary muscle contractions that can be painful and thwart progress — can end your race. An Olympic gold medal can spontaneously dissolve into a DNF. Because cramps have been around since muscles began contracting, we should have the answers. But the Krampus monster is sneaky. The risk of cramping varies from person to person. And, because of differences in environmental conditions on subsequent race days and changes in your fitness, your risk of cramping also varies from race to race. Consequently, it is important to identify your risk factors, intervene to minimise them, and have strategies on hand to deal with cramping if it occurs.If your current prevention and treatment approaches are based on a combination of a lack of knowledge, personal experience, anecdotes, and belief in a particular method, consider adding an evidence-informed preventative approach to your practice…

Start by thinking:

S.T.R.E.T.C.H.

Sleeping. Training. Resting. Eating. Travelling. Cooling. Hydrating.

This incorporates all the things that can cause fatigue and all the things associated with cramps. So, let’s examine them...

Sleeping. Training. Resting. Eating. Travelling. Cooling. Hydrating.

Now you are armed with preemptive prevention strategies. But, what if Krampus attacks during your race...

How can you treat cramps during running?

Anyone who follows soccer will have memories of players during extra time suddenly limping and falling to the ground in pain holding a hammie or calf. “Dehydration is setting in!”, the commentators would yell. Maybe. But, let’s not forget that these players have been intermittently sprinting, sweating balls for nearly 2-hours having consumed little. To pick that apart physiologically, I see a very long and unfamiliar high-intensity and highly-technical session very likely causing muscle damage coupled with an elevated core temperature, dehydration, and glycogen depletion, all causing physical and cognitive fatigue.So, when the cramp monster attacks, what can you do? Provide sympathy or, in the case of Lebron James, start an onslaught of “LeBroning” memes and publish completely uninformative “how to avoid cramps” articles? Or, do your homework…

An internet search will reveal a cauldron full of wonderful cramp-treating pills, potions, and “violent” tasting shots, including magnesium, sodium, vitamins, quinine, pickle juice, mustard, vinegar, capsaicin, ginger, and so on… The list is diverse, which means they cannot tackle the same cause. And, much of that list has not been studied, except through anecdotes. So, let’s look at what we do know...

When the cramping brings you down, your options are simple:

S.O.S.

Stop. Orally hydrate. Stretch.

Stop. Orally hydrate. Stretch.

The simple act of stopping, orally hydrating and stretching — S.O.S. — sounds nice and easy but it does not work for everyone and it does not work every time. Plus, if there is muscle damage, which is quite likely during a long, hard, and technical race, stretching a muscle may further exacerbate the problem by further damaging the tissue.

So, what else can you consider?

Of all the many pills and potions advertised on the internet, the experimental evidence is currently not convincing. For example, systematic reviews of the evidence do not support the use of quinine or magnesium for preventing or treating cramps. For other pills and potions, you will always find enticing anecdotes — some approaches may work sometimes for some athletes — but it doesn’t mean they will work for you. That said, having “belief” in an approach and the placebo effect can be a wonderful thing. But, there is no guarantee that the placebo effect is consistent — it is very likely that what worked for you once won’t work again in a different context. Nonetheless, if it is safe, legal and will not hinder performance, it is probably worth a shot to see whether it might help.

One biological mechanism with treatment potential being exploited by companies like HotShot and CrampFix, is transient receptor potential (TRP) channel agonists.

Say what?!

TRP channel agonists is a mouthful of hot and spicy jargon. In fact, that’s exactly what it is. TRP channel agonists being used for treating muscle cramps are hot and spicy foods, which activate receptors (called TRP channels) in your mouth and/or nasal cavity that trigger nerve impulses. These “shock” therapies taste pretty violent — they contain things like mustard, vinegar, ginger, capsaicin, etc. As you can tell, they don’t taste marvelous. What they do is not entirely clear. But, some work has shown such things to alleviate prolonged-contraction-induced cramping while other studies have found no effect on electrically-induced cramps.

There’s not a mass of data and such products have not been well studied, yet. They might help some people go “Yeah but nah... but yeaaah.”. If you want to try them, firstly make sure the product has been independently tested in the name of “clean sport”. Then, make sure you try the product during a long arduous session because you do not want to wait until race day to discover that it tastes like a shot of shit and makes you wanna emulate a veritable fountain of puke. But, the most important thing to consider if you are a regular cramper, is that no matter how sexy a transient receptor potential channel agonist sounds, a “shock” therapy won’t address the underlying cause of the cramping; it will simply mask the issue. So, I always recommend my athletes to start by picking the low hanging fruit:

Note: To go deeper on this topic, I can recommend Shawn Bearden’s SOUP podcast episode 115, a 2008 narrative review by Martin Schwellnus comparing neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion as causes of cramp, a 2019 narrative review by legends of cramp, Ron Maughan and Susan Shirreffs on causes and solutions, and a 2021 narrative review by current leaders in the field of cramp, including Kevin Miller and Martin Schwellnus.

What can you add to your cramp-eradication toolbox?

During a race, many factors are smashing your body’s homeostasis and causing fatigue and muscle damage, major culprits of cramps. Therefore, it is almost always impossible to assign your (poor) hydration status as the sole cause of your cramp-induced (failed) performance. So, don’t immediately blame your cramp-attack on dehydration and/or a lack of salt/sodium — they are a possible cause but not always the cause. Instead, think:And, most importantly,

And/or,

And,

×

![]()

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I am passionate about equality in access to free education. If you find value in my content, please help keep it alive by sharing it on social media and buying me a beer at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon. For more knowledge, join me @thomaspjsolomon on Twitter, follow @veohtu on Facebook and Instagram, subscribe to my free email updates at veothu.com/subscribe, and visit veohtu.com to check out my other Articles, Nerd Alerts, Free Training Tools, and my Train Smart Framework. To learn while you train, you can even listen to my articles by subscribing to the Veohtu podcast.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.