Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — How much fuel is in your body?

→ Part 2 — How do your muscles burn fuel?

→ Part 3 — How long can you go?

→ Part 4 — Carboloading

→ Part 5 — Race day carb availability

→ Part 6 — Putting it into practice

→ Part 1 — How much fuel is in your body?

→ Part 2 — How do your muscles burn fuel?

→ Part 3 — How long can you go?

→ Part 4 — Carboloading

→ Part 5 — Race day carb availability

→ Part 6 — Putting it into practice

Performance nutrition: Part 6 of 6:

Putting it into practice — how can you maintain high carbohydrate availability during a race?

Thomas Solomon PhD.

3rd July 2021.

If you have followed this series, you know why you should consider establishing high carbohydrate availability before your race — glycogen loading — and why you should consider maintaining high carbohydrate availability to your muscles during a race. Current sports nutrition guidelines are pretty clear but understanding their nuances will help you design your feeding plan. An awareness of race-day logistics is also key for maximizing your race-day performance. So, having a practical feeding plan is a vital part of logistical success. To wrap up this tasty series, today I will provide some practical “food for thought” to help shape your race-day feeding strategy.

Reading time ~25-mins.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Your bodily stores of carbohydrate (glucose) are limited. Since maintaining high carbohydrate availability is a key factor for endurance performance, for key races (and indeed also for key sessions), it is sensible to consider increasing your muscle glycogen stores beforehand — carbo-load before the race — and to maximise your liver glycogen store on race morning — eat carbs at breakfast. And, if the race (or session) is long — ~60-mins or more — it is sensible to consider sparing liver glycogen and providing continual carbohydrate availability to your muscles during the race — eat carbs during the race. Doing these simple things for a long duration race will help prevent hypoglycemia while maintaining fuel availability to “feed” your hungry muscles’ persistently high demand for ATP (energy). During a race where you wish to “compete”, your metabolic goal is to facilitate continuous, rapid, and forceful muscle contractions for as long as possible before fatigue.

There are many causes of fatigue but, from a metabolic perspective, muscle and liver glycogen depletion are golden tickets to meet Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue. In particular, if liver glycogen runs out, you can no longer maintain blood glucose levels in the healthy range and once they drop below ~3.5 mM (~0.6 g/L, or ~3 grams), signs of hypoglycemia will develop and signals will be sent to the brain causing muscle contractions to cease. In essence, it is all about saving the brain. If no glucose is available in the blood, the brain stops functioning and you perish. No matter what your habitual diet is, to fulfil your genetic potential on race day — to “compete” not merely “complete” — you will need to race with a high carb availability.

The recommended approaches for establishing and maintaining high carb availability are clear — you can hear all about them in Part 5 of this series — but there are some caveats…

Given these limitations, the massively important take-home from this whole series so far is that:

To put that knowledge into practice, let's take a look at something tasty...

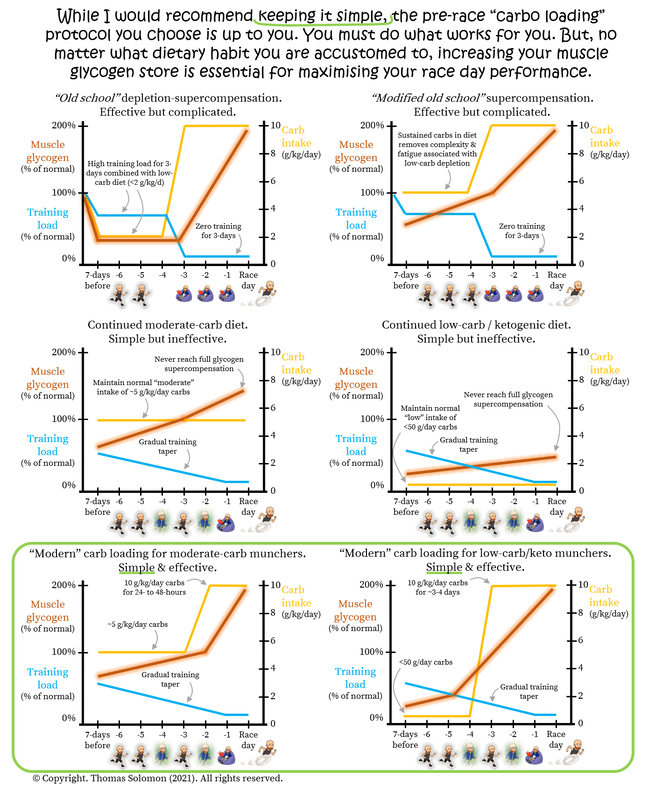

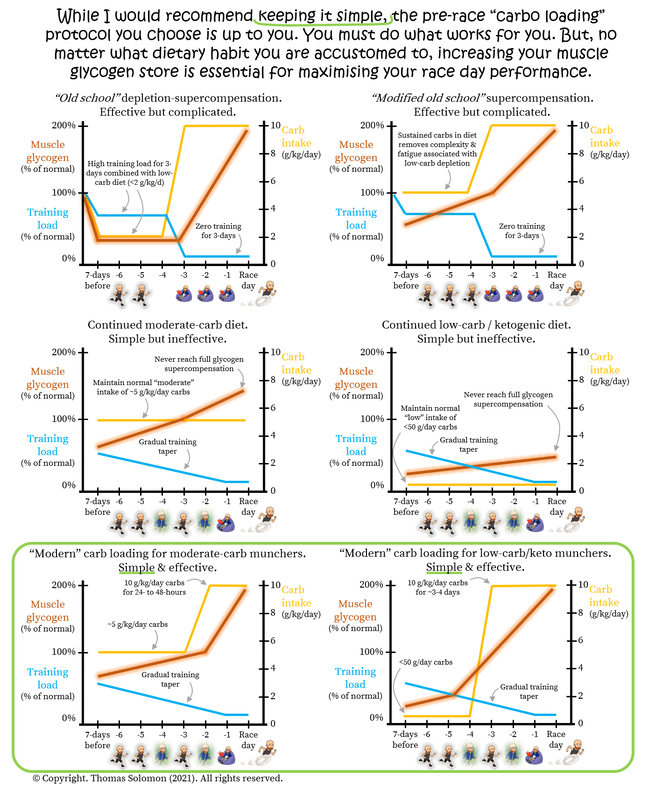

As I discussed in Part 4, the route to fill your muscles with glycogen does not have to be complicated. The old school depletion-supercompensation and modified depletion-supercompensation protocols are unnecessary for maximizing muscle glycogen in time for race day — 2-days of high-carb intake (aiming for 10 grams of carbs per kg bodyweight per day) is all you need.

Assuming you will take the simple and equally effective journey to glycogen supercompensation — a couple of days of high-carb intake — how will that look?

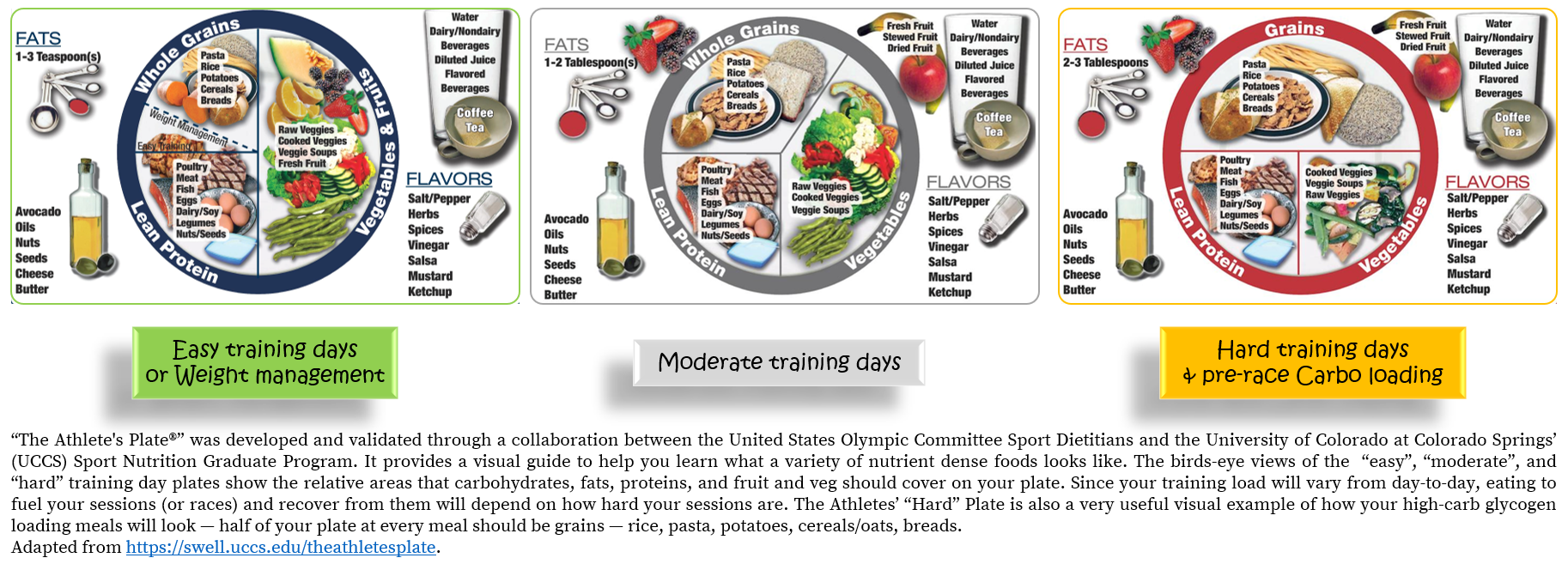

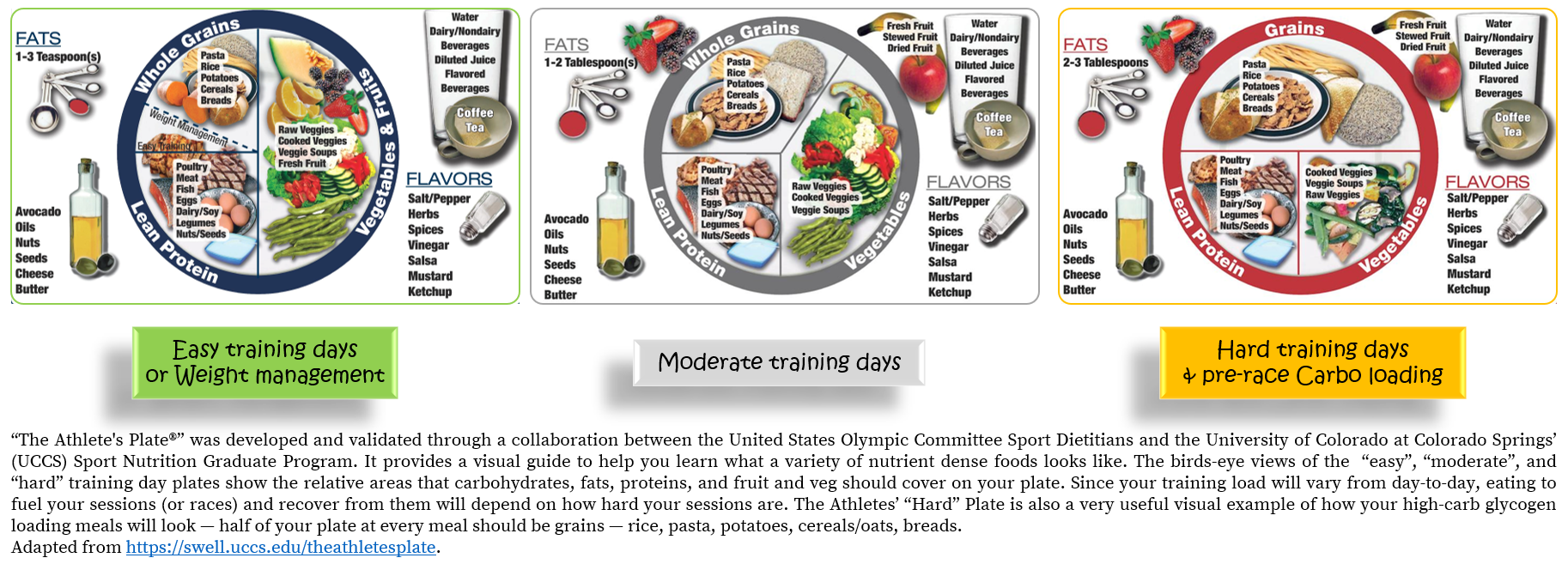

“The Athlete's Plate®” can be a useful guide. These birds-eye views of “easy”, “moderate”, and “hard” training day plates show the relative areas that carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and fruit and veg can be distributed on your plate at each meal. The plates were developed and validated at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs’ (UCCS) and are designed to provide a visual guide of what a variety of nutrient dense foods looks like. They do not suggest any caloric loads but are a visual tool to help learn 3 important facets of an athlete’s nutrition: The abundance and variety of whole foods… The presence of all food groups, including lean protein, at every meal… And, the increasing contribution of carbohydrate-containing foods as training intensity increases from easy to moderate to hard.

Since your training load will vary from day-to-day, eating to fuel your sessions (or races) and recover from them will depend on how hard your daily sessions are. So, The Athlete's Plate® provides useful visual clues as to how the relative amounts of the different food groups might vary in line with different daily training loads. Importantly, the Athletes’ “Hard” Plate is also a very useful visual example of how your high-carb glycogen loading meals might look — at least half of your plate at every meal should be grains — rice, pasta, potatoes, cereals/oats, breads, couscous, quinoa, polenta, etc.

I can comfortably eat ~3600 kcals per day during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load (I weigh 65 kg).

I can comfortably eat ~3600 kcals per day during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load (I weigh 65 kg).

I cannot eat 10 g/kg/day (~650 g/day) of carbs without feeling horrible.

I cannot eat 10 g/kg/day (~650 g/day) of carbs without feeling horrible.

I can comfortably eat 7 to 8 g/kg/day (~450-500 g/day) during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load (I typically eat 4 to 5 g/kg/day).

I can comfortably eat 7 to 8 g/kg/day (~450-500 g/day) during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load (I typically eat 4 to 5 g/kg/day).

I know what I like, what I have access to, and where to buy it. If I don’t, because I’m embarking on some race tourism, I bring the foods I need with me.

I know what I like, what I have access to, and where to buy it. If I don’t, because I’m embarking on some race tourism, I bring the foods I need with me.

My sources of carbs during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load come from oats, honey and/or brown sugar, bread, corn chips, and spaghetti, couscous, or rice, plus snacks in the form of dark chocolate, apples, bananas, berries, and usually about 80 grams of maltodextrin (a starch polysaccharide of glucose) dissolved in 1 L of water.

My sources of carbs during my 2-day pre-race glycogen load come from oats, honey and/or brown sugar, bread, corn chips, and spaghetti, couscous, or rice, plus snacks in the form of dark chocolate, apples, bananas, berries, and usually about 80 grams of maltodextrin (a starch polysaccharide of glucose) dissolved in 1 L of water.

This works for me. You are not me. Start building your evidence base today — learn what you like, what you don’t like, and how much you can handle. To help log your intake use a reputable and accurate nutrition database. (I suggest something like Nutritionix and their app.) [Note: I am not affiliated with or receiving royalties from Nutritionix; I just value and trust their product].

So, that will give you some food for thought for your pre-race carbo loading.

Next up...

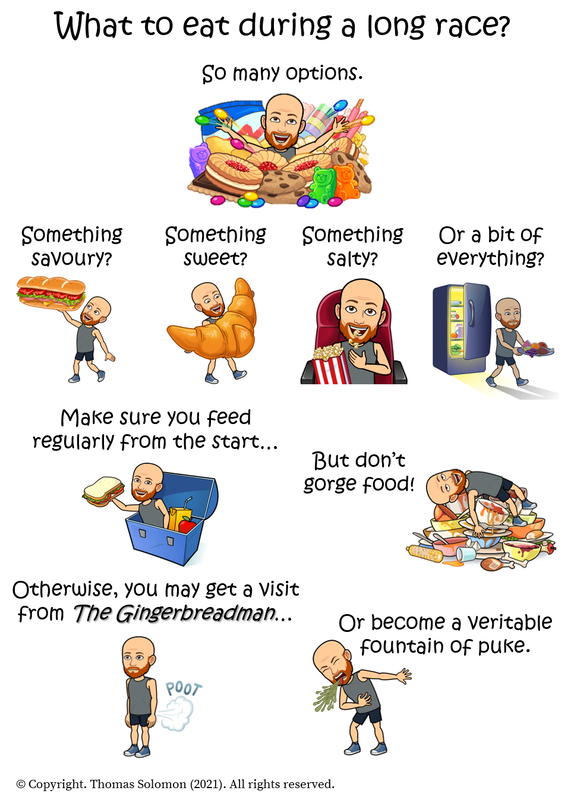

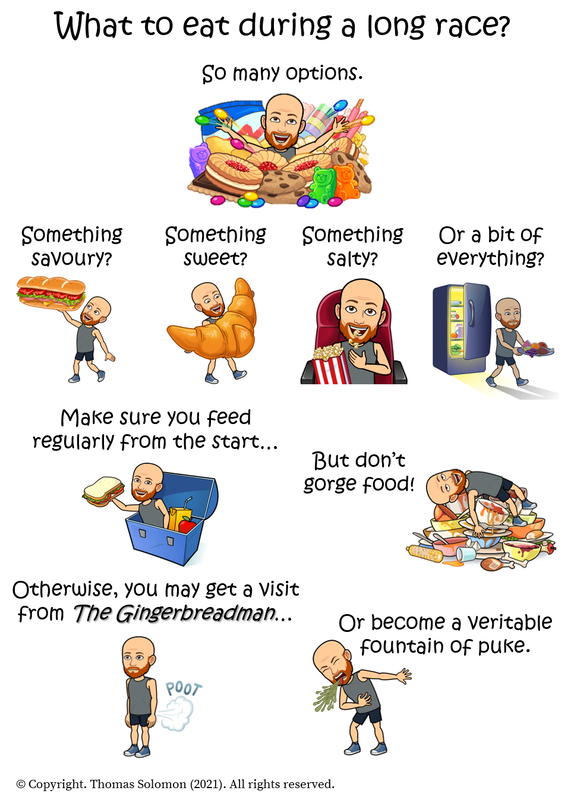

The guidelines state to aim for 1 to 4 g/kg of carbs around 1 to 4 hours before gun time. This is a massive range. And, for good reason... I know athletes who can eat ~4 g/kg of carbs within 2-hours of a race, chug beers, and do cartwheels, with no GI issues at all. On the contrary, some folks I have trained with or coached need as long as 4-hours having only eaten 1 to 2 g/kg and even then are anxious about meeting the gingerbreadman or becoming a veritable fountain of puke. Another consideration is the specific gun time: is it at 7 am? When do you need to wake to have time to digest? Do you typically race poorly after a short night of sleep?

A simple check for whether eating 2-hours before a race is enough time for you and/or whether you are trying to eat too much is to ask yourself, “do I feel full on the start line?”. If yes, you should try eating earlier before race time, i.e. 2 ½ hours. Some guidelines also advocate for consuming small amounts of carbs during the hour before gun time. But, I know many athletes, including myself, who experience signs of hypoglycemia during the early stages of a race when doing so. So, another question to ask yourself is, “Do I feel dizzy, light-headed, or lacking power in the first 20-30 mins of a race?”. If so, it is likely that the insulin response from the carbs (which causes muscles to remove glucose from blood) combined with the muscle contraction induced increase in muscle glucose uptake is causing your blood glucose levels to drop too low. Therefore, if this is the case, carb munching during the hour before the race is probably not for you.

Although I have had 26-years of gathering my empirical evidence, my tasty race morning breakfast has looked the same for the past 15-years — about 3-hours before gun time, no matter what time the gun fires, I eat the following:

Oats (100 grams, overnight soaked in 100 mL of cold 2% moo milk if hot weather, or “cooked” in 100mL of boiling water if cold weather).

Oats (100 grams, overnight soaked in 100 mL of cold 2% moo milk if hot weather, or “cooked” in 100mL of boiling water if cold weather).

Moo milk (2%, additional 100 mL).

Moo milk (2%, additional 100 mL).

Salt (½ gram of iodised table salt).

Salt (½ gram of iodised table salt).

Blueberries or Raspberries (a small handful).

Blueberries or Raspberries (a small handful).

Honey or brown sugar (40 grams). And

Honey or brown sugar (40 grams). And

Whey protein (15 grams). Plus,

Whey protein (15 grams). Plus,

Water-on-tap (volume to quench thirst, ice-cold if hot, and possibly with sodium if weather is fecking hot and humid and/or if the race is very long, e.g. >3-hours).

Water-on-tap (volume to quench thirst, ice-cold if hot, and possibly with sodium if weather is fecking hot and humid and/or if the race is very long, e.g. >3-hours).

This provides me with about 650 kcals of energy and about 110 grams of carbs to help replenish my liver glycogen. Since I weigh 65 kg, my race morning breakfast provides ~1.7 g/kg of carbs.

These are foods I like, always have available, always know where to source them, and are typically always available anyway in the world. If not, I bring them along. Also, this is typically very similar to what I eat every morning (the only difference is I add way more Blueberries and Raspberries, some seeds, some cashews or Peanut butter, and more protein, either more Whey [~20-30 grams] or 2 or 3 eggs). By keeping things similar, my race morning feels “normal” (ignoring the high probability of an impending visit from Darth Fader).

But you are not me. Remember: you are the only you — you need to practice your race-morning meals. Start building your evidence base today — learn what you like, what you don’t like, and how much you can handle. Food first but if food doesn’t work for you on race morning, try a supplemental carb-containing sports bar or beverage.

Nailing it. Now...

So, let’s delve into these things...

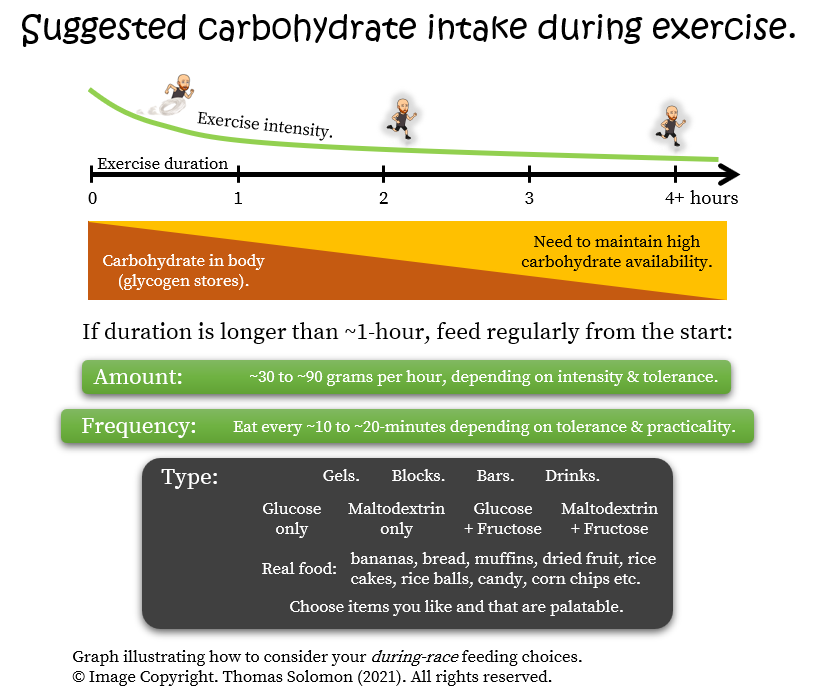

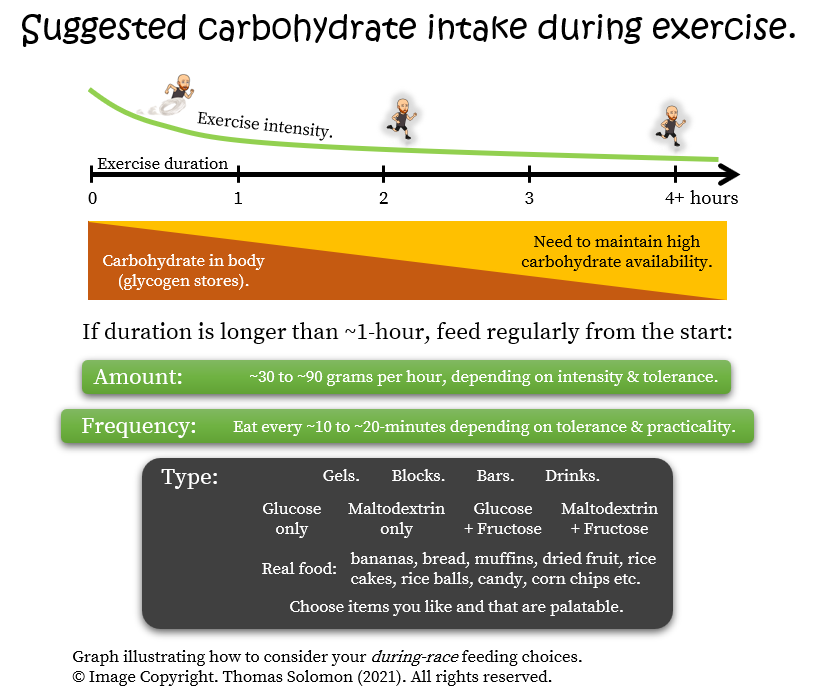

Remember that your initial decision as to whether during-race carb intake is necessary (or not) is shaped by the duration of the event. There is no need to feed during short-duration races (or sessions) lasting less than 60-minutes. Going beyond 60-mins and it becomes more likely that carb intake will help boost performance. Moving as fast as you can — high-intensity “competers” — will necessitate higher rates of carb intake to meet the high rate of carb oxidation. To accommodate that need, sports products (gels, bars, blocks, & drinks etc) that provide quickly-absorbed carbs may be more suitable. But for folks who are perhaps not moving as fast as possible — “completers” — the lower intensity will allow for a lower rate of during-race carb intake for which real foods can easily meet their metabolic demands.

To put this in context, 60 to 90 g/hour is the equivalent to eating:

~60 to 90 jelly beans

~60 to 90 jelly beans

or ~3 to 5 energy gels

~3 to 5 energy gels

or ~500 to 800 mL of Coke

~500 to 800 mL of Coke

or ~2 to 3 medium bananas

~2 to 3 medium bananas

or ~3 to 5 slices of white bread, every hour. None of which sounds very appetising to feast on for several hours.

~3 to 5 slices of white bread, every hour. None of which sounds very appetising to feast on for several hours.

The limiting factor to this maximal rate of orally-ingested carbohydrate oxidation during exercise is the ability of the intestine to absorb and deliver ingested carbohydrate into the blood. Even when carbs are eaten at a rate higher than 60 to 90 g/h during exercise, the rate at which they are “burned” does not exceed that value. This limitation is theorised to be the cause of maximal sustainable energy expenditure during extreme endurance events.

The implication of this limitation is that consuming more carbohydrate than you can “burn” increases the risk of accumulation of carbs in your gut and/or intestine, which leads delays gastric emptying, causes osmotic diuresis, increasing the risk of a subsequent visit from the gingerbreadman or becoming a veritable fountain of vomit. It is also important to know that diluting too much sugar in water will cause the same issue; hence why guidelines suggest 6–8% solutions (6 to 8 grams of carbs per 100 mL of water) are optimal. In the studies establishing sports nutrition guidelines, it was observed that some athletes could tolerate more, some less. I know first-hand, because I was a subject in very many of these studies and I am someone who does not deal well with extreme rates of carb intake (90+ g/h) during-exercise.

Whether humans can “gut train” their gastrointestinal system to absorb more carbs, as some sports nutritionists claim, is debatable — there is an absence of clinical evidence (but that isn’t necessarily evidence of absence and I will delve into that topic soon). However, whether there are physiological adaptations or not, you must practice and experiment with the dose that works for you.

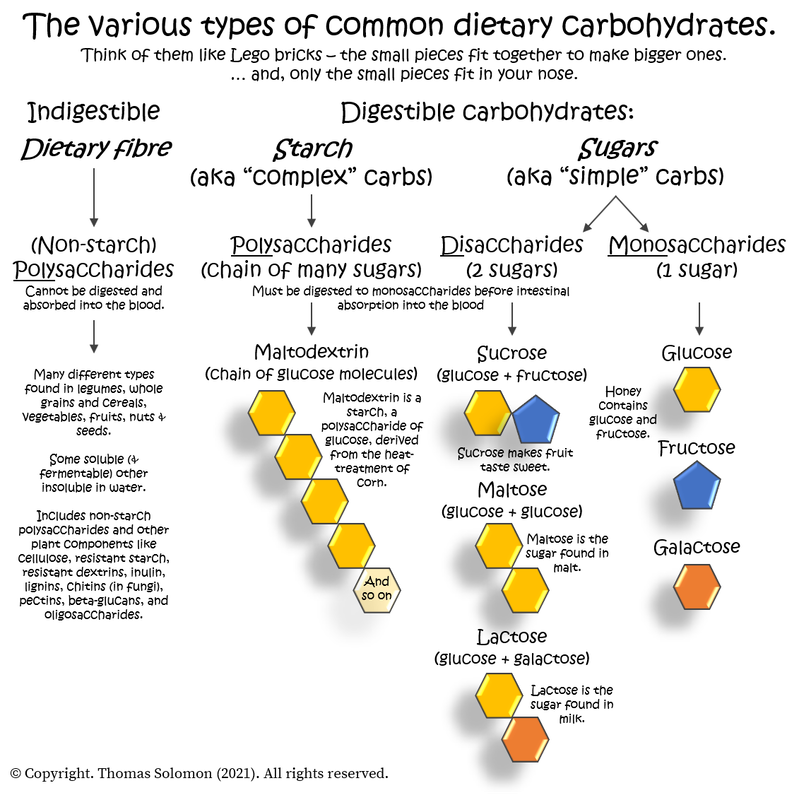

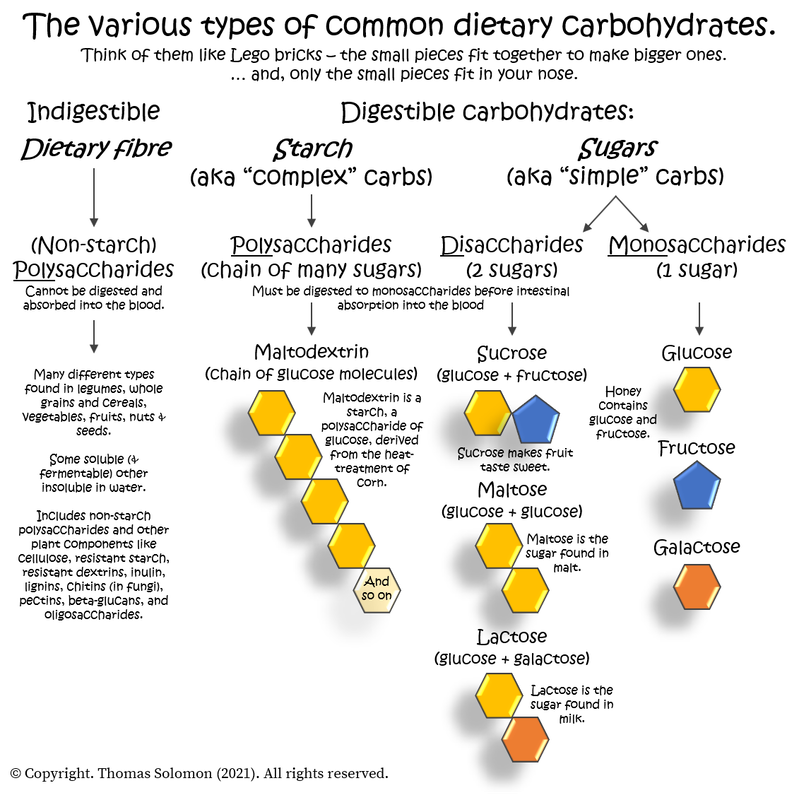

We eat and metabolise a symphony of carbohydrates, which have different tastes and metabolic/pharmacokinetic properties. But when it comes to intestinal absorption, we can only absorb sugars — all the digestible carbs we eat, which includes polysaccharide starch (e.g. maltodextrin, etc) and disaccharides (e.g. sucrose, lactose, maltose, etc) are digested and broken down into their monosaccharide building blocks: glucose, fructose, and galactose. To give this some context, grains, fruit, veg, and sweets all contain digestible and indigestible carbs (fibre). Table sugar is sucrose (a disaccharide of glucose and fructose). Honey contains glucose and fructose. Maltodextrin is a starch, a polysaccharide of glucose, derived from the heat-treatment of corn. But there are many other starches (complex carbs) and sugars (simple carbs) found in our diet, including lactose (the sugar found in milk that is a disaccharide of glucose and galactose).

No scientific evidence or marketing blurb can inform what will work for you — you are the only you. A basic rule of thumb is, “If you like the taste of it, it contains carbs at a rate that works for you, and does not make you feel sick, then that is the food for you”.

Some folks like gels, some like bars, some like real food, and some only ingest “sugar water” — Magda Boulet “relied exclusively on Roctane Energy Drink Mix for the entire 19 hours” to win the 2015 Western States 100) — that’s a lot of monotonous sticky fluid. Personally, I have tried all strategies with success and find no problems stomaching real food when running. But, you are not me. So, here are some nuances to help choose your foods.

During road marathons and trail/mountain/ocr races up to 3-hours, I find that water and performance gels (gels specifically designed for rapid sugar delivery into the blood that contain ~20 g of carbs in a blend of glucose/maltodextrin/fructose) work for me. I can tolerate (and just about like) those types of gels for up to 3-hours, consuming about 60 to 80 grams per hour — any more, I feel sick. I have experimented with many such gels and for me, it comes down to taste and palatability. I find that blackcurrant flavoured gels taste like vomit and I prefer that vomit only comes out of my belly, not into it.

I have also experimented with fluid only approaches, delivering glucose/maltodextrin and fructose dissolved in water at ~60-80 g/hour, and again find no problem in races up to 3-hours. For longer epics, I move towards a buffet of fluid (water and energy drink), gels, bars, and real food. And in doing so, I can tolerate ~80 g/hour for up to 7-hours (I’ve never run for longer than 7-hours). But the food-like additions to this menu have needed some experimentation. If I choose a crunchy cereal bar, I find they release solid lumps of hardness into my mouth that cause breathing issues as I fire food pellets either down my trachea or up my nasal cavity (or into the path of anyone nearby). So, I typically use softer bars or food (bread with banana/jam/honey/peanut butter).

As for performance gels, there’s a truckload of options... Science in Sport, Powerbar, Gu, the list is endless. But not all gels are created equally — the key consideration is their concentration, which, by extension, drives their osmolality (a kind of “liquid pressure” that describes how many “things”, carbs etc, are dissolved in water). What does that mean? Some gels are so highly-concentrated (lots of sugar, little water) that they have a higher osmolality than your blood and are said to be “hypertonic”. They draw water into your gut, slowing down the rate of absorption, increasing the risk of GI issues. You must drink water with these types of gels. But there are “isotonic” and “hypotonic” types of gels that contain carbs at a lower concentration because of their higher water content. Most energy drinks are “isotonic” but, of course, always check the label.

Another consideration is taste. Sugar (glucose & fructose, or sucrose) tastes very sweet while starch (e.g. maltodextrin) is near-tasteless. Many companies blend sugars with starch, making them less sweet. Some companies (like Maurten) use “hydrogel” technology to make products that are tasteless and very palatable but relatively expensive and, despite what their marketing and sponsored athletes are paid to say, the current evidence does not show that hydrogel-encapsulated carbs increase carb oxidation rates during exercise beyond that of non-hydrogel products (experimental evidence here, here, here, here, and here, and reviewed here). Other companies (like Vitargo and UCAN) even make starch-only products, which are also pretty low on sweetness.

Sports nutrition products designed to be ingested during exercise have traditionally contained carbohydrates (and caffeine, which will be discussed in a separate post) but such products are increasingly being laced with many other ingredients — fat, protein, specific fatty acids like medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), specific amino acids (like BCAAs), and ketone salts. While this is interesting, the entirety of the current evidence does not indicate that you should focus on those things first. For that reason, I will not discuss such things here but I am preparing an article on the evidence underpinning the utility (and lack thereof) of these “alternative” substrates in your race-day feeding strategy.

With the veritable smorgasbord of options available, remember to keep this post-it note at hand to remind you why you are eating during a race: help the liver, save the brain, support your hungry muscles. “Shorter” long races (e.g. ~1 to 3 hours) that you are planning to smash to “compete” will necessitate carb intake at the highest rate you can tolerate. In that scenario, eating fat-, protein-, and fibre-containing foods would simply delay carb transit through your stomach and absorption in your intestine. For “longer” long races (e.g. longer than 3-4 hours), to help increase the palatability of your carb intake strategy for the many hours you are out on the trails (and maintain adequate daily energy intake if your race is a Frodo-esque multi-day epic), then some fat-, protein-, and fibre-containing foods may help.

You must find what you like the taste of, what you can stomach, how much you can handle each hour.

Next up...

Individualized “grams per kilo” and “grams per hour” carb intakes sound pretty sexy but are a little reductionist because they ignore a key caveat every racer knows about: when and where are the opportunities to eat during a race? Therefore, for each race, you need a tailored plan that exploits the opportunities to eat throughout the race while minimising gut discomfort, maintaining high carb availability, and managing hunger.

Road marathons are logistically easy because there are feeding stations every 5 km, at which you usually know exactly what will be provided. Multi-loop trail and ultra races are also pretty easy since they pass a feeding zone at least once every 30- to 60-minutes — regular opportunities to feed, drink, and re-stock. Things get a little trickier during long-duration point-to-point or single-loop trail/ultra races, and even trickier in the mountains, because now you have to be largely self-sufficient and carry supplies — pack in, pack out. And, then there are obstacle races, where there are often no feeding stations, which can prove particularly problematic when you have several hours in the mountains with intermittent high-intensity bursts (obstacles/carries etc). So, to deal with these nuances, there are some considerations:

How will you know when to eat? That’s easy: just count to 60 fifteen times, that’s 15-minutes, time to eat. Just kidding. You can write timings on your arm or race number, or set an alarm on your watch (most GPS watches now have auto-repeating alarms), or use geographical triggers (feeding station or mile markers). Whatever you choose, aim to be frequent with your feeding rather than having a binge once an hour. And, be careful when trying to eat solid food on a climb because the increased breathing rate will cause said food to turn into bullets that either mow down your competitors or fire into your bronchioles, making breathing somewhat horrible. If you need to stop and walk to eat and drink, do it — seconds lost can be minutes gained. Don’t rush through a food station because you feel that stopping is bad; missing a feeding opportunity will be worse... and the consequence won’t reveal itself until it is too late. I got sucked into a fun mid-race “race” at a mountain marathon in 2020, whizzing down a descent in a group of folks — it was ace but I whizzed right past a food station I had planned to eat at. Naturally, the wheels fell off and the final few kms of that race sucked.

How will you know when to eat? That’s easy: just count to 60 fifteen times, that’s 15-minutes, time to eat. Just kidding. You can write timings on your arm or race number, or set an alarm on your watch (most GPS watches now have auto-repeating alarms), or use geographical triggers (feeding station or mile markers). Whatever you choose, aim to be frequent with your feeding rather than having a binge once an hour. And, be careful when trying to eat solid food on a climb because the increased breathing rate will cause said food to turn into bullets that either mow down your competitors or fire into your bronchioles, making breathing somewhat horrible. If you need to stop and walk to eat and drink, do it — seconds lost can be minutes gained. Don’t rush through a food station because you feel that stopping is bad; missing a feeding opportunity will be worse... and the consequence won’t reveal itself until it is too late. I got sucked into a fun mid-race “race” at a mountain marathon in 2020, whizzing down a descent in a group of folks — it was ace but I whizzed right past a food station I had planned to eat at. Naturally, the wheels fell off and the final few kms of that race sucked.

How will you carry your food/drink? In a bag, a bottle, a waist belt, or your shorts’ pockets? Bags are useful but can be bulky and over-the-top for many races. Hand-held bottles are great but get “sloshy” as they empty. Waist belts are also useful but I typically find that they either bounce around like a spacehopper or apply pressure on my colon — a gingerbreadman catalyst. Short pockets can be awesome but are limited for space. Or you can stick things down your shorts, but beware of food wrappers digging into your skin or the post-race shower will suck!

How will you carry your food/drink? In a bag, a bottle, a waist belt, or your shorts’ pockets? Bags are useful but can be bulky and over-the-top for many races. Hand-held bottles are great but get “sloshy” as they empty. Waist belts are also useful but I typically find that they either bounce around like a spacehopper or apply pressure on my colon — a gingerbreadman catalyst. Short pockets can be awesome but are limited for space. Or you can stick things down your shorts, but beware of food wrappers digging into your skin or the post-race shower will suck!

So, as part of your race day mastery, check the rules of the race to understand what you are allowed/not allowed/have to bring (for example, in most obstacle races you are not allowed outside assistance, which includes being given water or food from a spectator). Find out what will be and not be provided during the race — it can be a massive help to know which drinks/gels/foods will be at the feeding zones so you can use them in training. Plan where and when you will feed. And, without fail, learn to understand the demands of your race to inform the amount of carbs you will need and learn what you do and don’t like to eat/drink during a race so you can meet the demands with comfort — racing is tough enough; don’t allow your gut to be your downfall.

All of these considerations will also help you...

During some sessions, I advise folks to train as if it was race day — to wear the same kit and feed the same way. To help them start adapting to race day feeding, I start by advising them to ingest ~20 grams of carbs in gel, bar, or liquid form, starting every 30 to 40 mins and increasing the frequency of feeding every couple of weeks until they find a frequency that works for them. I advise that they find a food that they like and stick to it. Besides the debated possibility that you can “gut train”, what is very clear, is that you can and should train your during-race feeding strategy — the logistics, the feel, the timing, and so on — and practice it to the point it becomes intuitive. My athletes essentially conduct their own experiments with different products and feeding frequencies. Try the same — train your nutritional strategies during long sessions to maximise the chance of them working (metabolically and logistically) on race day. Practice race day.

I was fortunate to do my PhD in the lab where some of the g/min and glucose vs. fructose vs. maltodextrin knowledge was developed. I spent my entire career with access to the equipment I needed to dial in my personal carbohydrate and fat “burning” rates. For example, going into my first road marathon in 2008, I used indirect calorimetry to estimate that I could run for a long time (a marathon) at 3:45/km (6:00/mile) and that my body “burned” carbs at 3.8±0.3 g/min at that estimated marathon pace. I also knew that the volume of liquid my mouth could comfortably contain (98±10 mLs of fluid). Therefore, I knew that 3-mouthfuls of Lucozade Sport Orange (the drink provided every 5 km en route at the London marathon that contains 6.5 grams of glucose per 100 mL) would provide me with ~20-grams of carbs every 5 km (or 18-minutes). And, doing so at every food station would provide me with ~60-grams of carbs every hour. I also learned during that marathon that having 300 mL of fluids sloshing around in one's belly every 18-minutes is not ideal. But I also knew that my sweat rate (body fluid loss) at marathon pace in cool conditions (15 to 20°C) was ~1.5 liters per hour, so drinking ~900 mLs/hour would not place me at a higher risk of hyponatremia (low blood sodium caused by hyperhydration). In prep for that marathon, I also trained by setting up drinking tables at the track and doing drink station workouts to practice how to drink fluid while running at 3:45/km.

In subsequent marathons, I ditched energy drinks and used the least offensively tasting gels I could find while consuming water at drink stations to quench my thirst. Ahead of those races, I invested time working out the best ways I could carry gels — I tried belts, pockets, gloves, and even gaffer tape (the most effective and failsafe). Although my road marathon days are now long gone, these days, my favourite approach is to use shorts with side pockets and front and back zipped pockets. Since most of my time is now spent running in the mountains, I often run with a small pack with real food (very rarely gels) and water or I bring a drinking cup to get fluid from taps or natural springs. Plus, where I live there are hundreds of beer and sausage selling huts deep into the mountains — nutritional mastery achieved.

My example is not intended to suggest that you be so militant with g/min and mouth volume but to suggest that you experiment and adapt what works for you. Practicing your feeding plan regularly will help you develop contingency plans forif when it goes off the (t)rails. Practice will help you stay calm when things don’t go as planned. On race day, you might discover that a feeding zone was falsely advertised, or you might drop a gel, miss a bottle, or feel sick and not want to eat. Be calm. You are smart. Practice will help you find a solution. And, always remember that, if you can’t get the carbs down, at least get them in your mouth — a carbohydrate mouth rinse might boost your performance by increasing power output via stimulation of your central nervous system (see systematic reviews by Silva et al 2014 and Brietzke et al 2019, to be discussed in the future).

Sports nutrition guidelines are based on mean values, i.e. the average grams per minute rate of oxidation or average grams per hour rate of ingestion. Around the average there is a spread of values (the standard deviation) within which your oxidation rates and optimal intake rate will likely fall. ”You are the only you” and the sentiment of the need for an individualized approach is echoed in position statements from ACSM, IAAF, and ISSN, and roared by experts in the field. For these reasons, you must consider how you will establish and maintain high carbohydrate availability during your races (and key sessions).

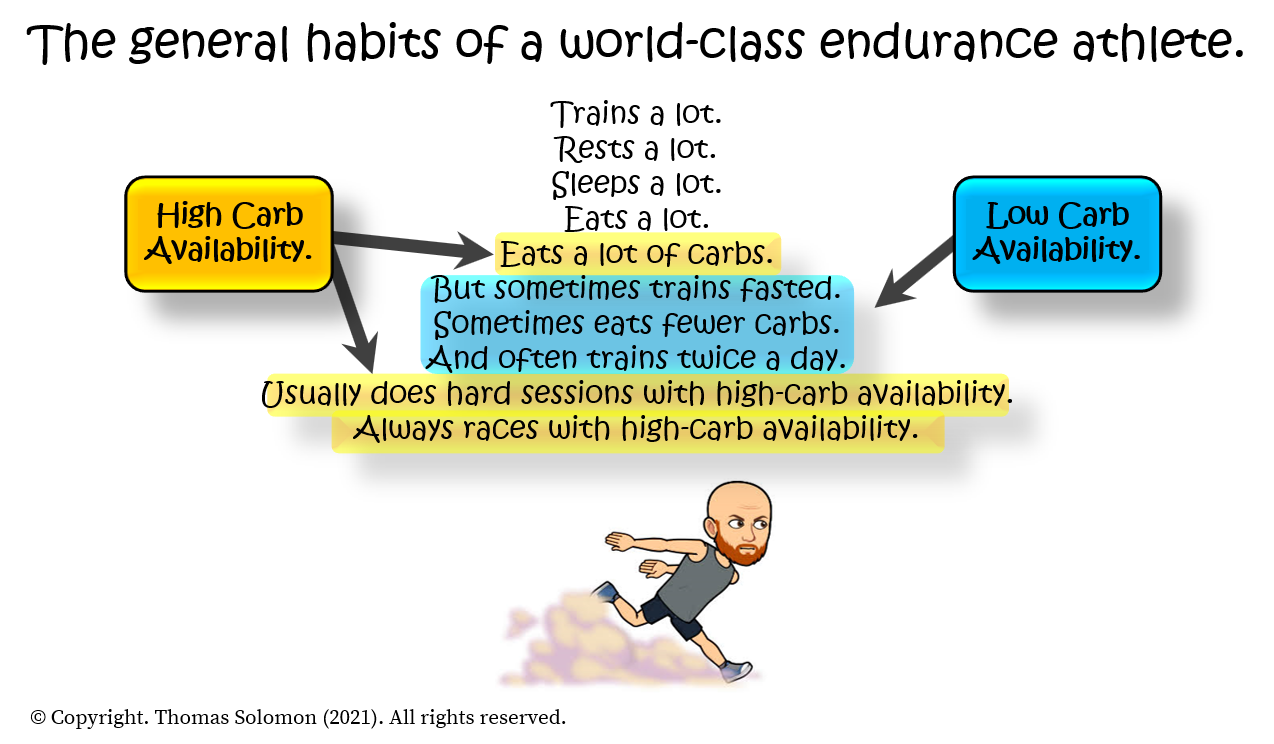

Yes, your body stores far more fat than glucose. And, yes, fat produces more energy (ATP) per gram than glucose. Therefore, being able to “burn” fat at a high rate for as long as possible is useful. But, glucose produces energy more rapidly than fat. And, glucose is more economical, producing more energy per litre of oxygen than fat. So, when operating at high intensities, when oxygen uptake (VO2) becomes a limiting factor because you are approaching your VO2max, it is entirely intuitive that your body will use the most economical fuel to keep moving forward fast with grace (or, at the very least, with a powerful war face).

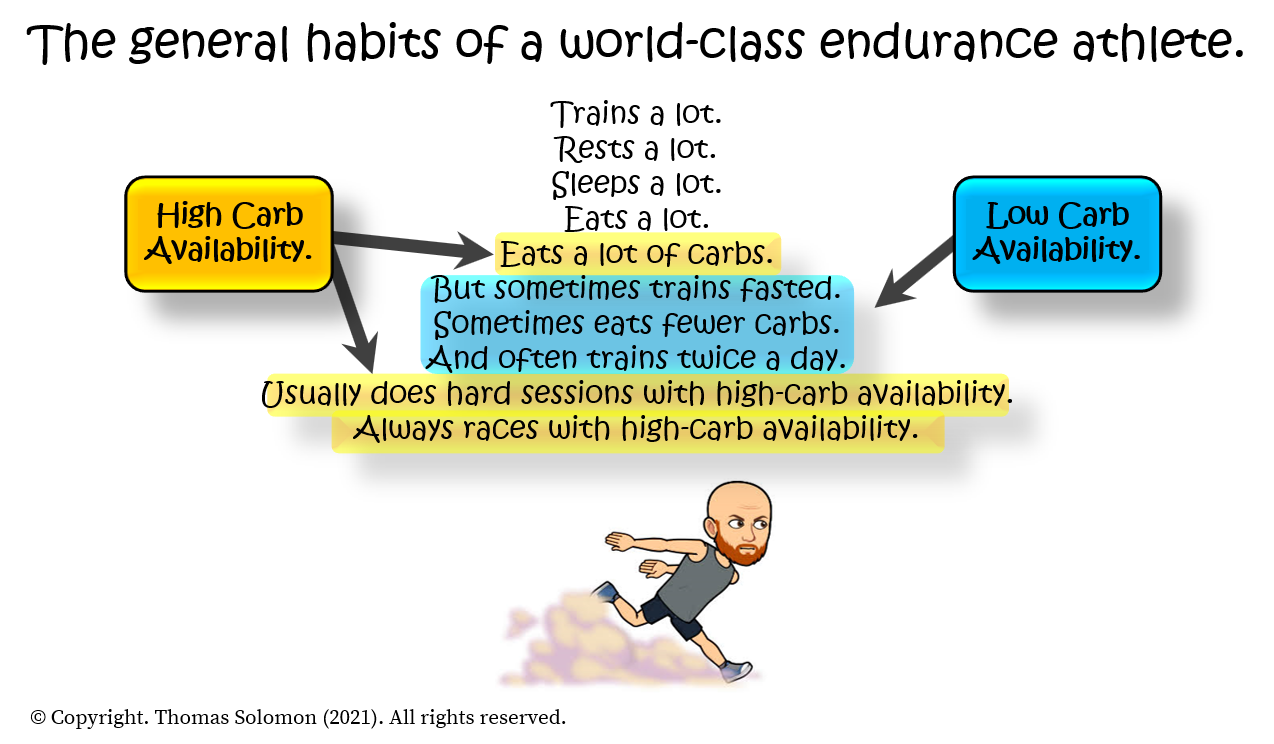

For these reasons, the metabolic goal of your training is to be fat and carb adapted — i.e. to have the ability to “burn” high amounts of fat for as long as possible but to also have the enzymatic and metabolic capacity to burn carbs at a high rate when you need to move fast (to go deep on that, see my series on Nutritional Manipulations for your Training). Meanwhile, the metabolic key to race success is high carbohydrate availability — i.e. if your glycogen stores are high and/or carbohydrates are ingested, you’ll be able to move fast when you need to. So, when wondering if you should always race with high carbohydrate availability… think: “Would you turn up to a gunfight with a sword in your hand?”... Of course not — always race with a high carbohydrate availability!

On this journey, I hope to have helped you understand that carbohydrates are your speedy friend. So, to leave you with a simple-to-remember take-home message to summarise the entirety of my banter on nutritional manipulations for training and performance:

You can train “low” some of the time but you should compete “high” all of the time.

You can train “low” some of the time but you should compete “high” all of the time.

And, to “compete high”, your performance nutrition can be simplified as follows:

Eat a high-carb diet for at least 2-days before race day, a high-carb breakfast on race morning, and eat carbs during your race

Eat a high-carb diet for at least 2-days before race day, a high-carb breakfast on race morning, and eat carbs during your race

And, keep it simple. You don’t need to overthink your performance nutrition:

Learn the basic needs of your event (how long is it?), and

Learn the basic needs of your event (how long is it?), and

Remember the basic biology of the human body (if the event is high-intensity and/or long-duration, your body will use glycogen and blood glucose as a fuel), then

Remember the basic biology of the human body (if the event is high-intensity and/or long-duration, your body will use glycogen and blood glucose as a fuel), then

Formulate a feeding strategy (to provide sufficient grams of carbs per hour) with products you like the taste of, then

Formulate a feeding strategy (to provide sufficient grams of carbs per hour) with products you like the taste of, then

Practice it (to find the strategy that works for you).

Practice it (to find the strategy that works for you).

Thanks for joining me on this journey back to 1920s Boston and into your muscles. Without your eyes and ears, I would not write. But please also consider contributing to my buy me a beer fund at buymeacoffee.com/thomas.solomon, which keeps my neurons uninhibited and creative during the writing process by maintaining a high carbohydrate availability.

Until next time, keep fueling smart.

There are many causes of fatigue but, from a metabolic perspective, muscle and liver glycogen depletion are golden tickets to meet Darth Fader, the Sith Lord of fatigue. In particular, if liver glycogen runs out, you can no longer maintain blood glucose levels in the healthy range and once they drop below ~3.5 mM (~0.6 g/L, or ~3 grams), signs of hypoglycemia will develop and signals will be sent to the brain causing muscle contractions to cease. In essence, it is all about saving the brain. If no glucose is available in the blood, the brain stops functioning and you perish. No matter what your habitual diet is, to fulfil your genetic potential on race day — to “compete” not merely “complete” — you will need to race with a high carb availability.

The recommended approaches for establishing and maintaining high carb availability are clear — you can hear all about them in Part 5 of this series — but there are some caveats…

Limitations in scientific evidence.

Nearly all of the systematic reviews on this topic (see Part 5 ) note a key observation: the between-study heterogeneity of study design is large — in other words, it is very difficult to compare trials because of their different protocols. There is also a lack of dose-response studies — I am only familiar with three dose-response RCTs (see here, here, and here) and they’re all in moderately-trained male cyclists. Furthermore, the vast majority of studies have been conducted using carbohydrate-containing fluids in young adult male cyclists. Little data is available in relation to race performance, in females, using other food formats or a combination of food/liquid/gels etc, and under conditions of heat-stress or during ultra-endurance exercise, where carbohydrate demands may differ. With specific attention to running, Patrick Wilson’s systematic review concluded that “studies should conduct trials under fed conditions, enroll women and adolescents, and carefully document blinding procedures”.Given these limitations, the massively important take-home from this whole series so far is that:

high carbohydrate availability is important for successful endurance racing but you must

find what works for you.

There is a veritable smorgasbord of sports products available, each one accompanied by a sexy marketing campaign. Should you be wary? Certainly. In 2018, the British Medical Journal dropped a bomb when they published a systematic analysis of sports products, science, and marketing by Carl Henneghan and colleagues from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: “Forty years of sports performance research and little insight gained”. The paper noted the general poor quality of study design and low quality of evidence in the field, concluding that “people should develop their own strategies for carbohydrate intake largely by trial and error”. While several scientists were pissed that their field was belittled, few can disagree with the authors’ sentiment that “people should develop their own strategies” — this is completely on-point. But, “little insight gained” is rather off-point. Through 100-years of research, we know the importance of glycogen stores and how to fill those stores, how to spare those stores, and how to keep an endurance athlete moving fast at a high-intensity for many hours (see Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5 of this series).

find what works for you.

To put that knowledge into practice, let's take a look at something tasty...

What does a glycogen loading feeding plan look like?

Daily nutrition is about making good choices to help follow a healthy eating pattern. The essence of healthy eating is to choose “food first” and to “take meals seriously but don’t stress. All is not lost if things get eff dup from time to time. Just aim to eat well on as many days as possible by including a variety of nutrient-dense foods of all colours across and within all food groups.” Your glycogen loading feeding plan is no different. “Carbo loading” before race day fills your muscles with glycogen to help them work harder for longer. Carbo loading is a “food first” approach — you do not need to be chugging bottle-after-bottle of “Energyzade” sugar water. As an athlete, you should never replace meals of real food with supplements. Supplements do what they say on the tin — they are for “supplementing” your real food.As I discussed in Part 4, the route to fill your muscles with glycogen does not have to be complicated. The old school depletion-supercompensation and modified depletion-supercompensation protocols are unnecessary for maximizing muscle glycogen in time for race day — 2-days of high-carb intake (aiming for 10 grams of carbs per kg bodyweight per day) is all you need.

×

![]()

If you do opt to use a depletion-supercompensation protocol, note that during the low-carb diet portion of these approaches (after the glycogen depleting exercise), you may experience signs of hypoglycaemia including fatigue and mood disturbances like irritability — aka “you might unnecessarily and inexplicably throw your toys out of the pram”. These depletion-supercompensation protocols might also make you feel anxious that you are not training at all. Plus, you need to make sure that you sustain your total energy availability by replacing lost carb calories with additional calories from fats and protein — an acute and drastic change in your diet can be tricky to perfect with foods you like and the unfamiliarity with excess fat/protein foods may cause gastrointestinal issues. It is not my agenda to tell you not to deplete-then-supercompensate but simply a heads up that it won’t be a cruise on the Danube and that you must practice-and-perfect it before your “A” race.

Assuming you will take the simple and equally effective journey to glycogen supercompensation — a couple of days of high-carb intake — how will that look?

“The Athlete's Plate®” can be a useful guide. These birds-eye views of “easy”, “moderate”, and “hard” training day plates show the relative areas that carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and fruit and veg can be distributed on your plate at each meal. The plates were developed and validated at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs’ (UCCS) and are designed to provide a visual guide of what a variety of nutrient dense foods looks like. They do not suggest any caloric loads but are a visual tool to help learn 3 important facets of an athlete’s nutrition: The abundance and variety of whole foods… The presence of all food groups, including lean protein, at every meal… And, the increasing contribution of carbohydrate-containing foods as training intensity increases from easy to moderate to hard.

Since your training load will vary from day-to-day, eating to fuel your sessions (or races) and recover from them will depend on how hard your daily sessions are. So, The Athlete's Plate® provides useful visual clues as to how the relative amounts of the different food groups might vary in line with different daily training loads. Importantly, the Athletes’ “Hard” Plate is also a very useful visual example of how your high-carb glycogen loading meals might look — at least half of your plate at every meal should be grains — rice, pasta, potatoes, cereals/oats, breads, couscous, quinoa, polenta, etc.

×

![]()

To reach the recommended 10 g/kg/day guideline during your carbo load, between meals you might choose to eat carb-containing snacks. Again, this does not mean that you need to eat candy and guzzle more “Energyzade”. Choose food first. But remember that 10 g/kg/day is a guide not a rule. I started experimenting with my carb loading approaches when I was 15. I now have 26 years of empirical evidence to learn from. Along my journey, my neurons have sculpted some important and bespoke rules:

So, that will give you some food for thought for your pre-race carbo loading.

Next up...

What does a race-morning meal look like?

A carb-containing breakfast replenishes your liver glycogen, which has been depleted after a night of sleep. Again, I will emphasise: choose food first. Eat a carb-containing meal. Don’t binge on fibre, protein, or fat. Options include cereals, oats, bread/toast, bagels, rice, pancakes, etc. When you eat food, it must pass through the stomach (gastric emptying) and the nutrients must be absorbed into the blood (intestinal absorption). Sugars (glucose/fructose) start to appear in the blood after ~5-10 minutes but it can take up to 2-4 hours for a carbohydrate meal to fully absorb, and longer for a mixed nutrient or high fat meal to absorb. Plus, it takes several hours for non absorbed matter (e.g. fiber) to travel through the large intestine to where the sun doesn't shine. Choose foods you like and foods that you know you can digest and tolerate.The guidelines state to aim for 1 to 4 g/kg of carbs around 1 to 4 hours before gun time. This is a massive range. And, for good reason... I know athletes who can eat ~4 g/kg of carbs within 2-hours of a race, chug beers, and do cartwheels, with no GI issues at all. On the contrary, some folks I have trained with or coached need as long as 4-hours having only eaten 1 to 2 g/kg and even then are anxious about meeting the gingerbreadman or becoming a veritable fountain of puke. Another consideration is the specific gun time: is it at 7 am? When do you need to wake to have time to digest? Do you typically race poorly after a short night of sleep?

A simple check for whether eating 2-hours before a race is enough time for you and/or whether you are trying to eat too much is to ask yourself, “do I feel full on the start line?”. If yes, you should try eating earlier before race time, i.e. 2 ½ hours. Some guidelines also advocate for consuming small amounts of carbs during the hour before gun time. But, I know many athletes, including myself, who experience signs of hypoglycemia during the early stages of a race when doing so. So, another question to ask yourself is, “Do I feel dizzy, light-headed, or lacking power in the first 20-30 mins of a race?”. If so, it is likely that the insulin response from the carbs (which causes muscles to remove glucose from blood) combined with the muscle contraction induced increase in muscle glucose uptake is causing your blood glucose levels to drop too low. Therefore, if this is the case, carb munching during the hour before the race is probably not for you.

Although I have had 26-years of gathering my empirical evidence, my tasty race morning breakfast has looked the same for the past 15-years — about 3-hours before gun time, no matter what time the gun fires, I eat the following:

These are foods I like, always have available, always know where to source them, and are typically always available anyway in the world. If not, I bring them along. Also, this is typically very similar to what I eat every morning (the only difference is I add way more Blueberries and Raspberries, some seeds, some cashews or Peanut butter, and more protein, either more Whey [~20-30 grams] or 2 or 3 eggs). By keeping things similar, my race morning feels “normal” (ignoring the high probability of an impending visit from Darth Fader).

But you are not me. Remember: you are the only you — you need to practice your race-morning meals. Start building your evidence base today — learn what you like, what you don’t like, and how much you can handle. Food first but if food doesn’t work for you on race morning, try a supplemental carb-containing sports bar or beverage.

Nailing it. Now...

What does a during-race feeding plan look like?

During-race carb feeding helps the liver and saves the brain, while supporting your hungry muscles. During race nutrition is where the “food first” rule has exceptions. The goal of during-race nutrition is to deliver carbohydrate to your working muscles quickly and continuously. To achieve this goal, you must consider the amount, type, and frequency of carbohydrate intake. Plus, no matter what the logical theory and experimental evidence might dictate, on race day there are two additional major considerations that will influence your feeding plan: personal preference (what you will eat) and logistics (how you will eat it).So, let’s delve into these things...

Consider the amount of carbohydrate intake.

Consider the amount of carbohydrate intake.

Remember that your initial decision as to whether during-race carb intake is necessary (or not) is shaped by the duration of the event. There is no need to feed during short-duration races (or sessions) lasting less than 60-minutes. Going beyond 60-mins and it becomes more likely that carb intake will help boost performance. Moving as fast as you can — high-intensity “competers” — will necessitate higher rates of carb intake to meet the high rate of carb oxidation. To accommodate that need, sports products (gels, bars, blocks, & drinks etc) that provide quickly-absorbed carbs may be more suitable. But for folks who are perhaps not moving as fast as possible — “completers” — the lower intensity will allow for a lower rate of during-race carb intake for which real foods can easily meet their metabolic demands.

As a side note → since there is an emerging area of nutritional research in the ultra running arena, which includes not only carbohydrate intake but also other macros (protein and fat) and supplements (amino acids, fatty acids, and ketones), I am preparing a separate post on that topic.

The recommendation to consume carbs during a race is not a recommendation to gorge unlimited amounts of carbs into your belly. Although us humans can “burn” as much as 5 grams of carbs per minute during exercise, our maximal rate of orally-ingested carbohydrate oxidation during exercise, lies, on average, somewhere between 1 and 1.5 grams per minute — or 60 to 90 grams per hour — which, you will no doubt notice, is very similar to the upper end of suggested carb intake guidelines.

To put this in context, 60 to 90 g/hour is the equivalent to eating:

or

or

or

or

The implication of this limitation is that consuming more carbohydrate than you can “burn” increases the risk of accumulation of carbs in your gut and/or intestine, which leads delays gastric emptying, causes osmotic diuresis, increasing the risk of a subsequent visit from the gingerbreadman or becoming a veritable fountain of vomit. It is also important to know that diluting too much sugar in water will cause the same issue; hence why guidelines suggest 6–8% solutions (6 to 8 grams of carbs per 100 mL of water) are optimal. In the studies establishing sports nutrition guidelines, it was observed that some athletes could tolerate more, some less. I know first-hand, because I was a subject in very many of these studies and I am someone who does not deal well with extreme rates of carb intake (90+ g/h) during-exercise.

Whether humans can “gut train” their gastrointestinal system to absorb more carbs, as some sports nutritionists claim, is debatable — there is an absence of clinical evidence (but that isn’t necessarily evidence of absence and I will delve into that topic soon). However, whether there are physiological adaptations or not, you must practice and experiment with the dose that works for you.

Consider the type of carbohydrate.

Consider the type of carbohydrate.

We eat and metabolise a symphony of carbohydrates, which have different tastes and metabolic/pharmacokinetic properties. But when it comes to intestinal absorption, we can only absorb sugars — all the digestible carbs we eat, which includes polysaccharide starch (e.g. maltodextrin, etc) and disaccharides (e.g. sucrose, lactose, maltose, etc) are digested and broken down into their monosaccharide building blocks: glucose, fructose, and galactose. To give this some context, grains, fruit, veg, and sweets all contain digestible and indigestible carbs (fibre). Table sugar is sucrose (a disaccharide of glucose and fructose). Honey contains glucose and fructose. Maltodextrin is a starch, a polysaccharide of glucose, derived from the heat-treatment of corn. But there are many other starches (complex carbs) and sugars (simple carbs) found in our diet, including lactose (the sugar found in milk that is a disaccharide of glucose and galactose).

×

![]()

Folks have been examining how the different types of carbs may aid performance for nearly 50-years. For example, in 1988, Tim Noakes and colleagues staged an outdoor 42 km marathon, for which runners tapered their training, were fed a high carb diet for 2-days before the race, ate a carb-containing breakfast on the morning of the race, and drank (on average) either 10-grams of glucose, or 38-grams of maltodextrin, or 44-grams of fructose every hour during the race. Performance was not different between the 3 types of carbs and muscle glycogen break down was not prevented but, importantly, blood glucose levels were maintained throughout the race with either carb approach.

However, the biochemistry of sugars provides one explanation of why different folks can handle different doses of carbs during exercise. Only consuming fructose in high amounts during exercise dramatically increases the risk of osmotic diuresis for most people — you will have an epic S.H.I.T (and I do not mean an epic Short High-Intensity Training session but Smelly & Hazardous Intestinal Turmoil). “Single-transporter” sugars like glucose are more suitable than fructose when eaten alone in high amounts. But it is also known that combining “multiple transporter” carbohydrates, e.g. glucose plus fructose can be even tolerated better when ingested in a 1:1 or 1:½ ratio and can help push that ingested oxidation rate up towards the 90 g/h mark. This is because glucose and fructose use different intestinal transporter proteins to be absorbed into the blood; hence ingesting them simultaneously lowers the risk of saturating either transport system. Maltodextrin, a polysaccharide starch made of a chain of glucose molecules, is a tasteless and palatable carb and, when combined with fructose in a 1:1 or 1:½ ratio, typically helps support the highest rates of orally-ingested carbohydrate oxidation with minimal GI discomfort. For a phenomenally detailed deep-dive on this specific topic, I can recommend a 2015 narrative review written by my friend Dave Rowlands.

So, toy around with the different types of carbs and combinations thereof — you might not like what is shown to be optimal, on average, because you might not respond like the average person.

The evidence indicates that using a carb feeding strategy is wise for events longer than ~60-minutes. But this does not mean that you should wait until the 60th minute to start dipping your face into the trough — failure to ingest carbohydrates from the outset of prolonged running increases reliance on muscle glycogen stores (which, as you know, cannot be replenished by subsequent carbohydrate ingestion late in exercise). Nor does it mean waiting until you detonate — hit the wall — during a race to start getting your feed on. We can all relate to the massive pick-me-up we get when eating something when we are completely eff dup. But the “surge” is short lived. By that point, it is too late to save your race — you will finish but you will no longer be competing just completing.

Consuming carbohydrates during a race does not mean you always need to have a sports drink/gel/bar in hand. But, ingesting frequent boluses of carbohydrate from the early stages of your race is sensible to ensure there is a constant availability of glucose to your muscles and a constant sparing of liver glycogen. Aim to find your optimal frequency by aiming to eat somewhere in the region of every 10 to 30-minutes. Interestingly, some evidence shows that too frequent a feed (e.g. every 5-minutes) actually lowers the rate at which you can “burn” ingested carbs during running when compared to every 20-mins.

To put this in context, let’s say that you can handle 60 grams of carbs per hour and you like to do so with energy gels. Each energy gel contains ~20 grams of carbs so

Eating 1 energy gel every 20-minutes will provide you with 60 g of carbs every hour. This still might not sound very appetising but does sound manageable.

Eating 1 energy gel every 20-minutes will provide you with 60 g of carbs every hour. This still might not sound very appetising but does sound manageable.

So, have a play with your feeding frequency. Learn how often you can tolerate feeding. During a race, it is never too late to feed but don’t leave it late to start your feed. Start your carb feeding early in the race and continue it for as long as you can but also know when to stop — piling calories onto a full stomach will quickly transform you into a human version of Old Faithful.

However, the biochemistry of sugars provides one explanation of why different folks can handle different doses of carbs during exercise. Only consuming fructose in high amounts during exercise dramatically increases the risk of osmotic diuresis for most people — you will have an epic S.H.I.T (and I do not mean an epic Short High-Intensity Training session but Smelly & Hazardous Intestinal Turmoil). “Single-transporter” sugars like glucose are more suitable than fructose when eaten alone in high amounts. But it is also known that combining “multiple transporter” carbohydrates, e.g. glucose plus fructose can be even tolerated better when ingested in a 1:1 or 1:½ ratio and can help push that ingested oxidation rate up towards the 90 g/h mark. This is because glucose and fructose use different intestinal transporter proteins to be absorbed into the blood; hence ingesting them simultaneously lowers the risk of saturating either transport system. Maltodextrin, a polysaccharide starch made of a chain of glucose molecules, is a tasteless and palatable carb and, when combined with fructose in a 1:1 or 1:½ ratio, typically helps support the highest rates of orally-ingested carbohydrate oxidation with minimal GI discomfort. For a phenomenally detailed deep-dive on this specific topic, I can recommend a 2015 narrative review written by my friend Dave Rowlands.

So, toy around with the different types of carbs and combinations thereof — you might not like what is shown to be optimal, on average, because you might not respond like the average person.

Consider the frequency of carbohydrate intake.

Consider the frequency of carbohydrate intake.

The evidence indicates that using a carb feeding strategy is wise for events longer than ~60-minutes. But this does not mean that you should wait until the 60th minute to start dipping your face into the trough — failure to ingest carbohydrates from the outset of prolonged running increases reliance on muscle glycogen stores (which, as you know, cannot be replenished by subsequent carbohydrate ingestion late in exercise). Nor does it mean waiting until you detonate — hit the wall — during a race to start getting your feed on. We can all relate to the massive pick-me-up we get when eating something when we are completely eff dup. But the “surge” is short lived. By that point, it is too late to save your race — you will finish but you will no longer be competing just completing.

Consuming carbohydrates during a race does not mean you always need to have a sports drink/gel/bar in hand. But, ingesting frequent boluses of carbohydrate from the early stages of your race is sensible to ensure there is a constant availability of glucose to your muscles and a constant sparing of liver glycogen. Aim to find your optimal frequency by aiming to eat somewhere in the region of every 10 to 30-minutes. Interestingly, some evidence shows that too frequent a feed (e.g. every 5-minutes) actually lowers the rate at which you can “burn” ingested carbs during running when compared to every 20-mins.

To put this in context, let’s say that you can handle 60 grams of carbs per hour and you like to do so with energy gels. Each energy gel contains ~20 grams of carbs so

×

![]()

Use foods that suit your personal preference.

Use foods that suit your personal preference.

No scientific evidence or marketing blurb can inform what will work for you — you are the only you. A basic rule of thumb is, “If you like the taste of it, it contains carbs at a rate that works for you, and does not make you feel sick, then that is the food for you”.

Some folks like gels, some like bars, some like real food, and some only ingest “sugar water” — Magda Boulet “relied exclusively on Roctane Energy Drink Mix for the entire 19 hours” to win the 2015 Western States 100) — that’s a lot of monotonous sticky fluid. Personally, I have tried all strategies with success and find no problems stomaching real food when running. But, you are not me. So, here are some nuances to help choose your foods.

During road marathons and trail/mountain/ocr races up to 3-hours, I find that water and performance gels (gels specifically designed for rapid sugar delivery into the blood that contain ~20 g of carbs in a blend of glucose/maltodextrin/fructose) work for me. I can tolerate (and just about like) those types of gels for up to 3-hours, consuming about 60 to 80 grams per hour — any more, I feel sick. I have experimented with many such gels and for me, it comes down to taste and palatability. I find that blackcurrant flavoured gels taste like vomit and I prefer that vomit only comes out of my belly, not into it.

I have also experimented with fluid only approaches, delivering glucose/maltodextrin and fructose dissolved in water at ~60-80 g/hour, and again find no problem in races up to 3-hours. For longer epics, I move towards a buffet of fluid (water and energy drink), gels, bars, and real food. And in doing so, I can tolerate ~80 g/hour for up to 7-hours (I’ve never run for longer than 7-hours). But the food-like additions to this menu have needed some experimentation. If I choose a crunchy cereal bar, I find they release solid lumps of hardness into my mouth that cause breathing issues as I fire food pellets either down my trachea or up my nasal cavity (or into the path of anyone nearby). So, I typically use softer bars or food (bread with banana/jam/honey/peanut butter).

As for performance gels, there’s a truckload of options... Science in Sport, Powerbar, Gu, the list is endless. But not all gels are created equally — the key consideration is their concentration, which, by extension, drives their osmolality (a kind of “liquid pressure” that describes how many “things”, carbs etc, are dissolved in water). What does that mean? Some gels are so highly-concentrated (lots of sugar, little water) that they have a higher osmolality than your blood and are said to be “hypertonic”. They draw water into your gut, slowing down the rate of absorption, increasing the risk of GI issues. You must drink water with these types of gels. But there are “isotonic” and “hypotonic” types of gels that contain carbs at a lower concentration because of their higher water content. Most energy drinks are “isotonic” but, of course, always check the label.

Another consideration is taste. Sugar (glucose & fructose, or sucrose) tastes very sweet while starch (e.g. maltodextrin) is near-tasteless. Many companies blend sugars with starch, making them less sweet. Some companies (like Maurten) use “hydrogel” technology to make products that are tasteless and very palatable but relatively expensive and, despite what their marketing and sponsored athletes are paid to say, the current evidence does not show that hydrogel-encapsulated carbs increase carb oxidation rates during exercise beyond that of non-hydrogel products (experimental evidence here, here, here, here, and here, and reviewed here). Other companies (like Vitargo and UCAN) even make starch-only products, which are also pretty low on sweetness.

Sidenote → I do not have any affiliations with, nor do I receive any royalties from, the brands or products I mention.

Besides performance gels, companies like Spring Energy, Muir Energy, and Hüma Gel, make “real food” gels, a somewhat paradoxical term for a processed “gel” contained in a plastic wrapper, but they can taste pretty good. And, of course, there is real food. You know, the stuff we evolved to eat. Some folks choose bananas, bread, muffins, dried fruit, rice cakes, rice balls, candy, corn chips… the choice is yours. But remember that, in addition to carbohydrates, food gels and real food typically contain a blend of many things. So, some thought should be given to their fibre content — too much fibre during running = increased visitation risk from the gingerbreadman — and their fat and protein content — macronutrients that you do not necessarily need to eat to fuel a prolonged high-intensity effort and which delay the gastric emptying and absorption of carbohydrate, the fuel you do need to keep on rocking.

Sports nutrition products designed to be ingested during exercise have traditionally contained carbohydrates (and caffeine, which will be discussed in a separate post) but such products are increasingly being laced with many other ingredients — fat, protein, specific fatty acids like medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), specific amino acids (like BCAAs), and ketone salts. While this is interesting, the entirety of the current evidence does not indicate that you should focus on those things first. For that reason, I will not discuss such things here but I am preparing an article on the evidence underpinning the utility (and lack thereof) of these “alternative” substrates in your race-day feeding strategy.

With the veritable smorgasbord of options available, remember to keep this post-it note at hand to remind you why you are eating during a race: help the liver, save the brain, support your hungry muscles. “Shorter” long races (e.g. ~1 to 3 hours) that you are planning to smash to “compete” will necessitate carb intake at the highest rate you can tolerate. In that scenario, eating fat-, protein-, and fibre-containing foods would simply delay carb transit through your stomach and absorption in your intestine. For “longer” long races (e.g. longer than 3-4 hours), to help increase the palatability of your carb intake strategy for the many hours you are out on the trails (and maintain adequate daily energy intake if your race is a Frodo-esque multi-day epic), then some fat-, protein-, and fibre-containing foods may help.

You must find what you like the taste of, what you can stomach, how much you can handle each hour.

Next up...

Plan the logistics.

Plan the logistics.

Individualized “grams per kilo” and “grams per hour” carb intakes sound pretty sexy but are a little reductionist because they ignore a key caveat every racer knows about: when and where are the opportunities to eat during a race? Therefore, for each race, you need a tailored plan that exploits the opportunities to eat throughout the race while minimising gut discomfort, maintaining high carb availability, and managing hunger.

Road marathons are logistically easy because there are feeding stations every 5 km, at which you usually know exactly what will be provided. Multi-loop trail and ultra races are also pretty easy since they pass a feeding zone at least once every 30- to 60-minutes — regular opportunities to feed, drink, and re-stock. Things get a little trickier during long-duration point-to-point or single-loop trail/ultra races, and even trickier in the mountains, because now you have to be largely self-sufficient and carry supplies — pack in, pack out. And, then there are obstacle races, where there are often no feeding stations, which can prove particularly problematic when you have several hours in the mountains with intermittent high-intensity bursts (obstacles/carries etc). So, to deal with these nuances, there are some considerations:

All of these considerations will also help you...

Practice your feeding plan!

None of what you have learned in this series matters unless you practice — The correct load, type, and frequency of carbohydrate-containing foods you like is nuanced to you. Nutrition is part of your training; to master race-day, you MUST practice your feeding plan.During some sessions, I advise folks to train as if it was race day — to wear the same kit and feed the same way. To help them start adapting to race day feeding, I start by advising them to ingest ~20 grams of carbs in gel, bar, or liquid form, starting every 30 to 40 mins and increasing the frequency of feeding every couple of weeks until they find a frequency that works for them. I advise that they find a food that they like and stick to it. Besides the debated possibility that you can “gut train”, what is very clear, is that you can and should train your during-race feeding strategy — the logistics, the feel, the timing, and so on — and practice it to the point it becomes intuitive. My athletes essentially conduct their own experiments with different products and feeding frequencies. Try the same — train your nutritional strategies during long sessions to maximise the chance of them working (metabolically and logistically) on race day. Practice race day.

I was fortunate to do my PhD in the lab where some of the g/min and glucose vs. fructose vs. maltodextrin knowledge was developed. I spent my entire career with access to the equipment I needed to dial in my personal carbohydrate and fat “burning” rates. For example, going into my first road marathon in 2008, I used indirect calorimetry to estimate that I could run for a long time (a marathon) at 3:45/km (6:00/mile) and that my body “burned” carbs at 3.8±0.3 g/min at that estimated marathon pace. I also knew that the volume of liquid my mouth could comfortably contain (98±10 mLs of fluid). Therefore, I knew that 3-mouthfuls of Lucozade Sport Orange (the drink provided every 5 km en route at the London marathon that contains 6.5 grams of glucose per 100 mL) would provide me with ~20-grams of carbs every 5 km (or 18-minutes). And, doing so at every food station would provide me with ~60-grams of carbs every hour. I also learned during that marathon that having 300 mL of fluids sloshing around in one's belly every 18-minutes is not ideal. But I also knew that my sweat rate (body fluid loss) at marathon pace in cool conditions (15 to 20°C) was ~1.5 liters per hour, so drinking ~900 mLs/hour would not place me at a higher risk of hyponatremia (low blood sodium caused by hyperhydration). In prep for that marathon, I also trained by setting up drinking tables at the track and doing drink station workouts to practice how to drink fluid while running at 3:45/km.

In subsequent marathons, I ditched energy drinks and used the least offensively tasting gels I could find while consuming water at drink stations to quench my thirst. Ahead of those races, I invested time working out the best ways I could carry gels — I tried belts, pockets, gloves, and even gaffer tape (the most effective and failsafe). Although my road marathon days are now long gone, these days, my favourite approach is to use shorts with side pockets and front and back zipped pockets. Since most of my time is now spent running in the mountains, I often run with a small pack with real food (very rarely gels) and water or I bring a drinking cup to get fluid from taps or natural springs. Plus, where I live there are hundreds of beer and sausage selling huts deep into the mountains — nutritional mastery achieved.

My example is not intended to suggest that you be so militant with g/min and mouth volume but to suggest that you experiment and adapt what works for you. Practicing your feeding plan regularly will help you develop contingency plans for

×

![]()

What can you put in your performance nutrition toolbox?

To quote Louise Burke and John Hawley, “Modern sports nutrition offers a feast of opportunities to assist elite athletes to train hard, optimize adaptation, stay healthy and injury free, achieve their desired physique, and fight against fatigue factors that limit success.”Sports nutrition guidelines are based on mean values, i.e. the average grams per minute rate of oxidation or average grams per hour rate of ingestion. Around the average there is a spread of values (the standard deviation) within which your oxidation rates and optimal intake rate will likely fall. ”You are the only you” and the sentiment of the need for an individualized approach is echoed in position statements from ACSM, IAAF, and ISSN, and roared by experts in the field. For these reasons, you must consider how you will establish and maintain high carbohydrate availability during your races (and key sessions).

Yes, your body stores far more fat than glucose. And, yes, fat produces more energy (ATP) per gram than glucose. Therefore, being able to “burn” fat at a high rate for as long as possible is useful. But, glucose produces energy more rapidly than fat. And, glucose is more economical, producing more energy per litre of oxygen than fat. So, when operating at high intensities, when oxygen uptake (VO2) becomes a limiting factor because you are approaching your VO2max, it is entirely intuitive that your body will use the most economical fuel to keep moving forward fast with grace (or, at the very least, with a powerful war face).

For these reasons, the metabolic goal of your training is to be fat and carb adapted — i.e. to have the ability to “burn” high amounts of fat for as long as possible but to also have the enzymatic and metabolic capacity to burn carbs at a high rate when you need to move fast (to go deep on that, see my series on Nutritional Manipulations for your Training). Meanwhile, the metabolic key to race success is high carbohydrate availability — i.e. if your glycogen stores are high and/or carbohydrates are ingested, you’ll be able to move fast when you need to. So, when wondering if you should always race with high carbohydrate availability… think: “Would you turn up to a gunfight with a sword in your hand?”... Of course not — always race with a high carbohydrate availability!

On this journey, I hope to have helped you understand that carbohydrates are your speedy friend. So, to leave you with a simple-to-remember take-home message to summarise the entirety of my banter on nutritional manipulations for training and performance:

Until next time, keep fueling smart.

×

![]()

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.