Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 1 — Hypothermia

→ Part 2 — Risk management

→ Part 3 — Cold acclimation

Also check out my related series on:

Training & racing in the heat.

→ Part 1 — Hypothermia

→ Part 2 — Risk management

→ Part 3 — Cold acclimation

Also check out my related series on:

Training & racing in the heat.

Training & racing in the cold. Part 2 of 3:

How to stay warm and minimise your risk of hypothermia.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

First released: 17th Feb 2020.Updated & re-released: 16th Oct 2021.

If you joined me for Part 1 of this series, you are now well-informed about the risks of winter training and what hypothermia is. To continue with my quest to help you train smart, here in Part 2 I will delve into what you can do before you step out the door to help manage your risk of succumbing to the dark side of the winter — evaluate your energy status and clothing choices.

Reading time ~22-mins (4000-words).

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

The phrase, risk management, sounds bloody boring but in cold weather it could save your life. That aside, looking through the less morbid “glasses of optimism”, risk management of the cold may keep you progressing through a race or a training session when those around you are fading into the abyss. So, to help yourself consistently train smart through the winter, your first step is to identify the cold hazards and then take steps to mitigate them.

Learning to recognize changes in weather conditions will help alert you to necessary changes in your plans that will reduce cold exposure and reduce the risk of cold injuries. Hypothermia most often develops when you are not prepared for it. If you think things are bad, they will likely get worse. Unexpected rain and/or wind, or unexpected and/or colder-than-expected water immersion can come as a shock and remove large amounts of body heat. As I explained in Part 1, body heat loss is much greater in cold, wet, and windy conditions, and if exercise intensity is not high enough to offset body heat loss, this is when the risk of developing hypothermia is greatest. Therefore, continually reevaluate as more input information becomes available.

As a guide, you can commit to memory a risk management checklist, some of which is adapted from the American College of Sports Medicine’s position stand on the prevention of cold injuries during exercise:

How cold is it outside today?

How cold is it outside today?

What is the air temperature where you are? What is the expected air temperature where you will go (e.g. altitude)? What is the humidity? What is the wind speed? What will be the level of natural shelter? For current weather updates check your local Met Office webpage.

What conditions might I encounter?

What conditions might I encounter?

Are wind, rain, snow, and/or water immersion possible? Know how the expected weather will affect the terrain, e.g. mudslides, wet rocks, avalanches, impassable rivers, strong winds on exposed ridgelines, etc. I was removed from a racecourse and taken to hospital with hypothermia in 2018 when the mid-race temperature abruptly plummeted from +5oC to -5oC as the beast from the east hit the British Isles. This mercury drop combined with high winds, snow, water immersion, and inadequate clothing for the unexpected weather, led to a night of cardiac monitoring and warm soup.

What other factors might affect my body heat retention?

What other factors might affect my body heat retention?

The time of day. Your level of fitness. Your level of fatigue from prior sessions. Your experience. Your general health. Your body size and/or body fat level. The planned exercise intensity and duration. Your feeding and hydration status. The availability of shelter. Standing still - if you are at a race and are forced to stand around before the start or after you have finished, find something to stand on in addition to boots and socks to insulate your feet from the frozen ground - cardboard, foam, or carpet scraps; a trick I have picked up from Austrians standing at ski or bobsleigh events. Water immersion - during an OCR race, do your utmost to keep your head, neck, and shoulders out of the water. If you are able to wade, keep your hands and arms out of the water. Loss of dexterity in your hands will not only prevent you completing rigs and climbing ropes in an OCR race but will also prevent you opening drinks bottles and food packets thus limiting your hydration status and fuel supply to keep you working at a high intensity and generating heat.

What can I do to exercise safely in the cold today?

What can I do to exercise safely in the cold today?

Plan your route – if you are in an unfamiliar area, use local resources or web resources to check the routes and conditions. Lots of offline maps are available for download so you can set your smartphone to low power mode and flight mode to preserve battery life. My favourite offline trail resource is the maps.me app. Tell someone where you’re headed, how long you will be, who is with you, what supplies you have, and what your ETA is. Take supplies but don’t overload – food, fluid, phone, spare clothing, contact numbers, head torch. Obtain accurate weather reports. Use an appropriate feeding and hydration strategy. Use proper clothing and equipment, and plan clothing changes if required. Plan shelter for re-warming at the end.

What can I do when I am out there?

What can I do when I am out there?

Conduct self-checks: ask yourself, “How do I feel? Am I still OK?”. Conduct buddy-checks if you’re with others. Evaluate the changing conditions. Be sensible, know your limits, and abort mission when necessary. Yes, adventure is the goal but know when it is time to stop, seek shelter, and turn back. My wife and I recently aborted a summit on Mount Taranaki when we emerged onto an exposed ridgeline where fog had set in, the rain was lashing down, and the wind speed was knocking us off our feet. Equipped with waterproof gear and good sense, we turned back and all we needed was a little hot chocolate to warm back up.

These five simple questions will help you identify the hazards and assess the risks, and thereby help keep the dark side at bay. So, plan ahead and help yourself train safe.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

No matter how many times weather forecasters will try to convince us, looking into the future is not an accurate endeavour and the weather is out of our control. In Part 1, I alluded to some of the “controllable” factors that can exploit to help mitigate your risk of hypothermia. These include your energy status and clothing choices.

If you can maintain normal core body temperature, cold exposure during exercise does not directly increase oxygen consumption (and therefore caloric requirements) above normal, even in windy conditions. However, it is important to remember that you are still likely to expend slightly more energy during exercise in the cold. This is because your effort level through snow or mud is greater and because you may be carrying more load, like heavier clothing and backpacks for spare food and clothing. You will also expend more energy if you start shivering, but the intention of this series of articles is for you never to get to that point.

Maintaining blood glucose levels within the normal range while maximising muscle glycogen stores will help prevent hypothermia. These physiological goals will also prolong the duration at which you can maintain high-intensity exercise under all conditions. Therefore, it is sensible to include carbohydrates in your diet if you are an athlete seeking to maximise your performance outcome. If you are able to maintain your core and/or muscle temperature, fatigue is most often related to carbohydrate availability rather than thermoregulatory limitations and exercise can be sustained by ingesting carbohydrate in cold conditions. Because maintaining carbohydrate availability is key, it has been shown that maximizing muscle glycogen with carbohydrate loading before exercise in the cold is beneficial.

At breakfast, to replenish your liver glycogen store (which is depleted overnight) and top-up your muscle glycogen stores, and also to provide some warmth from the thermic effect of metabolising food, eat carbohydrate-containing foods.

At breakfast, to replenish your liver glycogen store (which is depleted overnight) and top-up your muscle glycogen stores, and also to provide some warmth from the thermic effect of metabolising food, eat carbohydrate-containing foods.

To prevent a drop in blood glucose levels during a long-duration and/or high-intensity activity, take carbohydrate-containing foods with you, foods that suit your tastes and practicalities of the session/race. These will provide a glucose source to fuel your activity and spare muscle glycogen while also providing a thermic effect to help keep you warm. You might choose energy products like bars, gels, and drinks, but you may also opt for carbohydrate-rich foods like crackers, cereals, or bread.

Plan to bring fluid with you during long sessions.

Plan to bring fluid with you during long sessions.

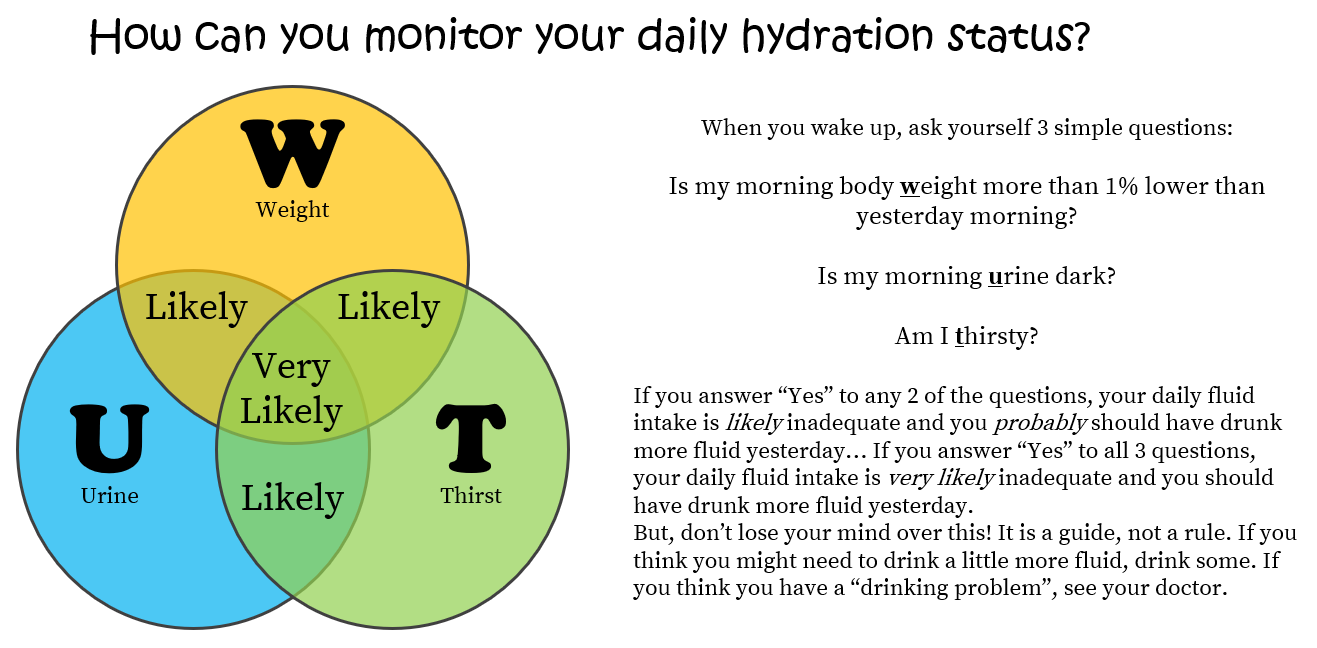

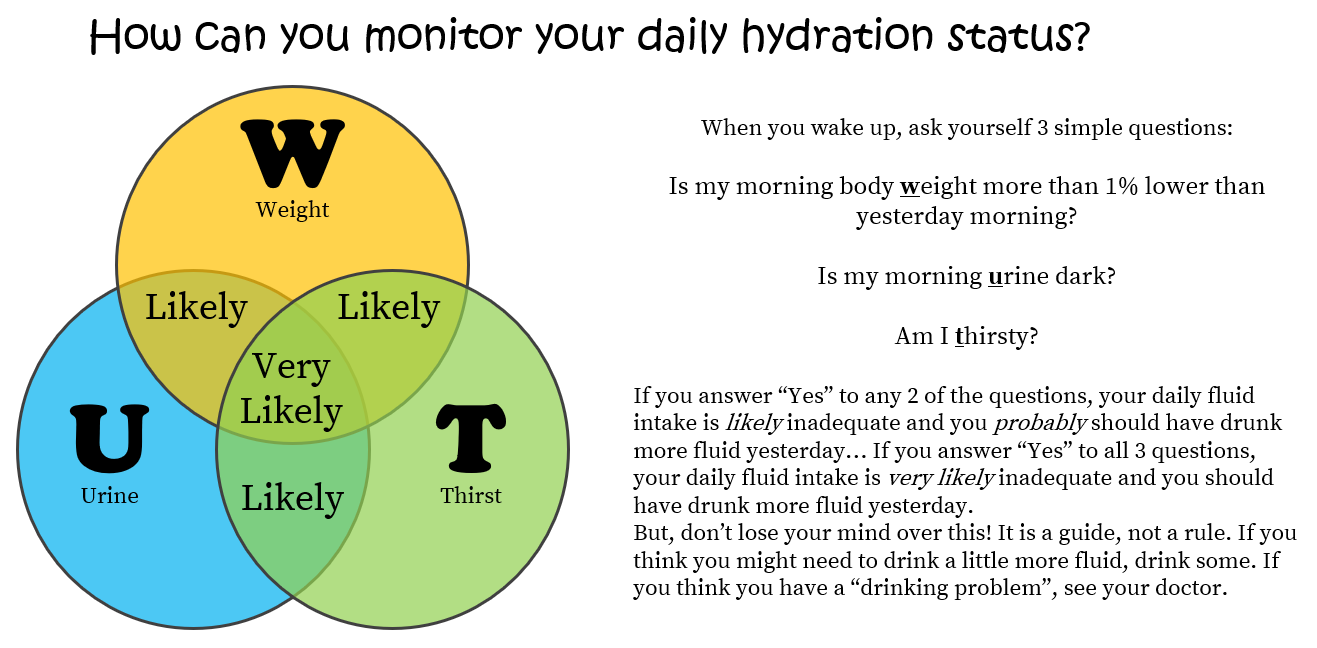

I have learned not to rely on en route water taps in the winter as they are often turned off. But, generally, learning to monitor your hydration is wise so as to optimise performance year-round. To do this during exercise, keep it simple: drink to thirst. Meanwhile, monitoring your daily hydration status is covered in detail in a separate article but you can get started by saying “W U T?” , which provides a useful indication of hydration status in healthy active folks. What? Your daily hydration status can easily be determined by daily tracking of your morning body Weight, Urine colour, and feeling of Thirst. So,to assess your daily hydration status, every morning ask yourself 3 simple questions:

Is my morning body Weight more than 1% lower than yesterday morning? (Note that up to a 1% variation in daily body weight is normal — e.g. up to 0.6 kg if you weigh 60 kg.)

Is my morning body Weight more than 1% lower than yesterday morning? (Note that up to a 1% variation in daily body weight is normal — e.g. up to 0.6 kg if you weigh 60 kg.)

Is my morning Urine dark?

Is my morning Urine dark?

Am I Thirsty?

Am I Thirsty?

If you answer “Yes” to any 2 of the questions, your daily fluid intake is likely inadequate and you probably should have drunk more fluid yesterday… If you answer “Yes” to all 3 questions, your daily fluid intake is very likely inadequate and you should have drunk more fluid yesterday. But, don’t lose your mind over this… It is a guide, not a rule. If you think you might need to drink a little more fluid, drink some. If you think you have a “drinking problem”, see your doctor.

Re-used from Robert W Kenefick, Samuel N Cheuvront’s Hydration for recreational sport and physical activity. Nutrition Reviews (2012).

Avoid cotton.

Avoid cotton.

Cotton is rubbish. When it is wet, cotton retains water, gets heavy, is abrasive, and cools you down fast. I spent my teenage years training in Pearl Jam t-shirts and retro-style event t-shirts. My teenage grunge image was haunted by many a bloody nipple and numerous shivering, bollock-freezing moments. Ditch the “old school” t-shirts but keep listening to Pearl Jam.

Love wool.

Love wool.

Wool is ace. It wicks moisture, is insulative, and, when wet, stays insulative. Use wool base layers and mid layers on your extremities, your torso, your head, and your baby-making bits. Yes, Merino wool products can be expensive but I have never regretted wearing them and there are high-quality, low-cost options around, like the Mountain Warehouse own-brand products, which I have used successfully for several years.

Invest in Gore-Tex.

Invest in Gore-Tex.

Windproof, waterproof, and breathable, Gore-Tex and similar compounds, like Pertex, have combined these important facets into a single material and are an essential addition to your clothing arsenal. Such fabrics are expensive but I have learned from much trial and error that they are worth the investment - some things are just not worth scrimping on.

Layer your clothing.

Layer your clothing.

The aim is to be warm but not excessively sweaty, which will promote heat loss. Layering provides a flexible way to adjust your clothing on the fly to prevent overheating and sweating so as to remain dry. Also aim to avoid bulkiness, which can slow you down and/or cause pressure points that reduce circulation. Typical cold-weather clothing consists of three layers:

Base. A lightweight layer in direct contact with your skin that does not absorb moisture but wicks it to the outer layers to evaporate. Your base layer of cold weather clothing needs to wick perspiration. Microfiber, polyester/polypropylene, or wool products that aren't scratchy all work well.

Base. A lightweight layer in direct contact with your skin that does not absorb moisture but wicks it to the outer layers to evaporate. Your base layer of cold weather clothing needs to wick perspiration. Microfiber, polyester/polypropylene, or wool products that aren't scratchy all work well.

Middle. Your primary insulative layer which holds the heat you are generating. A polyester fleece or wool product can work well, as can down if the temperature is super low and you are moving super slow. The thickness of the middle layer needs to be adjusted depending on the conditions and your work rate.

Middle. Your primary insulative layer which holds the heat you are generating. A polyester fleece or wool product can work well, as can down if the temperature is super low and you are moving super slow. The thickness of the middle layer needs to be adjusted depending on the conditions and your work rate.

Outer. Your protective layer stops wind and rain coming in while allowing moisture to transfer from your body to the air, without adding unnecessary bulk. The outer layer is a tricky one to master because your sweat rate can easily exceed the vapor transfer rate of the outer material, causing moisture to accumulate on the inside. An outer with vented armpit zips can be useful and remember that the outer layer need not be worn during exercise unless it is raining or very windy.

Outer. Your protective layer stops wind and rain coming in while allowing moisture to transfer from your body to the air, without adding unnecessary bulk. The outer layer is a tricky one to master because your sweat rate can easily exceed the vapor transfer rate of the outer material, causing moisture to accumulate on the inside. An outer with vented armpit zips can be useful and remember that the outer layer need not be worn during exercise unless it is raining or very windy.

Invest in your hand-shoes.

Invest in your hand-shoes.

I couldn’t resist dropping one of my favourite German words: Handschuhe. Gloves are essential and will help maintain warmth and dexterity. Using a layering system similar to your normal clothing is very sensible. I have had a lot of success training in the winter with a thin merino glove liner (base) under a heavier wool glove (middle) under a Gore-Tex mitten (outer). The layering is easy to change on the fly. But, like all clothing approaches, do not wait until your hands are cold to put gloves on. Also, as a word of warning, do not blow warm breath into your hand-shoes because the vapour in your breath will add moisture to the glove which will contribute to further cooling, especially if it freezes.

If you stop for a break, add a layer.

If you stop for a break, add a layer.

When you stop moving, your body temperature will drop more rapidly in cold conditions. So, if you stop for food or water, or just for some banter, put on a layer.

Don’t wear too much right away.

Don’t wear too much right away.

When you step out that door, if you start with too many layers you will overheat and sweat. You’ll stop to take off a layer but, because you are wet underneath, then you’ll cool down rapidly and get cold. The solution, leave the house wearing fewer layers and take a pack with extra clothes. To look like a pro, many big name brands make packs of varying sizes that are useful for carrying gear, but they can be expensive. More pocket-friendly options can be found at Decathlon which stocks affordable and good-quality trail running backpacks made by Kalenji and trail running tights that have several zippered pockets for carrying gear.

Protect the muscles that you will need.

Protect the muscles that you will need.

At rest, muscle provides insulation during cold-water immersion but during exercise blood flow increases and the muscle’s insulative property is lost. Using clothing to cover and insulate active muscle is, therefore, very sensible if your race in is cold conditions and will include water immersion.

Protect your lungs.

Protect your lungs.

If the air is cold and dry, exercise can increase the risk of cold-induced bronchoconstriction even if you are healthy. One little trick to helping prevent and remedy this is to wrap a scarf or a buff loosely over your mouth and nose, not so tight that it impedes your breathing but just enough to humidify your breath.

Consider neoprene.

Consider neoprene.

In races that require frequent and/or prolonged water immersion, using neoprene clothing or even a full neoprene wetsuit is sensible and popular and within the rules of most OCR events. Note: as people involved in OCR will know, as of 2020 there is no current universal rule book that governs all races, so check the rules of your event. If the water immersion section requires swimming, neoprene increases core temperature, reduces drag, increases buoyancy and lowers oxygen consumption at a given speed. This is advantageous and in OCR races not yet deemed an unfair performance enhancement. Even without a full wetsuit, neoprene clothing like gloves, rash vests, arm sleeves, and head caps are also useful for maintaining limb-specific thermal balance and limiting heat loss. Protecting the head is particularly important since heat loss from your noggin can be as high as 50% of your total heat production when sitting at -4oC (25oF). A neoprene cap is easy to take on and off and wearing a wool liner under a neoprene cap has consistently proven to be a very useful way to combat mid-race cold water immersion.

Prioritise time in finding great socks.

Prioritise time in finding great socks.

Cotton is a no go - it holds moisture, becomes heavy, and is abrasive when wet. Merino wool socks are a great choice for warmth and fast-drying properties but, as always, it is a matter of personal choice and comfort is a priority. So, try several different types in wet and cold conditions and stick to what works for you. But, take note, don’t double up on socks or wear socks that are too tight - this will restrict adequate blood flow - and remember that thicker socks will require a slightly larger shoe to accommodate them. Also remember that your feet will still sweat in the cold, particularly in heavy boots. A build-up of moisture around your feet for prolonged periods will increase the risk of trench foot. So, if you plan to be out there working hard for several hours in cold and/or wet conditions, always bring one or two changes of socks.

Prioritise time in finding grippy, stable, and quick-draining shoes.

Prioritise time in finding grippy, stable, and quick-draining shoes.

As for shoes, again you can pick all sorts of brands and models, some are even made with Gore Tex in the uppers but it is again a matter of personal choice. Two important lines of thought when choosing a winter shoe are “water drainage”, i.e. shoes need to empty water quickly once dunked and not be sponge-like, and “grip”. Personally, I have never found GoreTex in running shoes to be particularly useful - it adds extra weight and only protects you from incoming moisture that does not rise above the ankle, which in winter is almost never. Slipping, however, is a big issue because not only will it lose you time and places in a race but it can also cause serious injury and even be fatal in the mountains. There is no single shoe that will tackle every type of terrain but there are some shoe companies like Inov8 and VJ Sports that have invested large amounts of time into the soles of their shoes and use a variety of rubbers to help with wet rocks and even ice studs to help in snowy/icy conditions. Other brands like Hoka have partnered with Vibram to provide grippy soles. Again, personal comfort trumps any recommendation, so try some out. Many trail running stores have “try out” days where brands host days where you can borrow a pair of shoes for the day and destroy them on the trails at no cost or hidden agenda to have to purchase - this is a great way to decide which shoe might work for you. If you live in particularly icy conditions, I have had great success when living in Denmark, the US, Austria, and the UK, using Yaktrax attached to the outside of my shoes. In very snowy conditions, as I experienced in the midwest of Ohio and here in Austria, I use snowshoes for a lot of my winter running to great effect. Whatever you choose to put on your feet, side with comfort, and don’t lace too tightly - in a race, your metatarsal companions will be strapped to your feet for many hours, so form a friendly symbiotic relationship with them.

Choose a sensible shoe that meets World Athletics’ regulations.

Photo: Davide Ligabue on Unsplash.

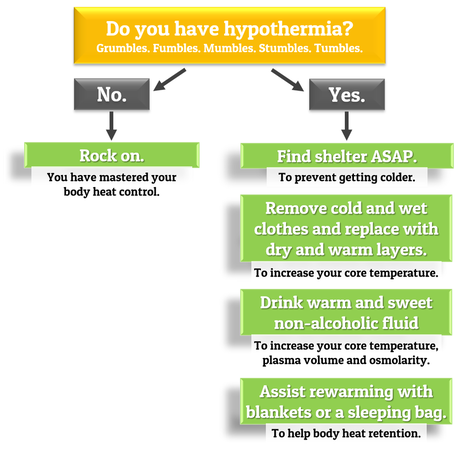

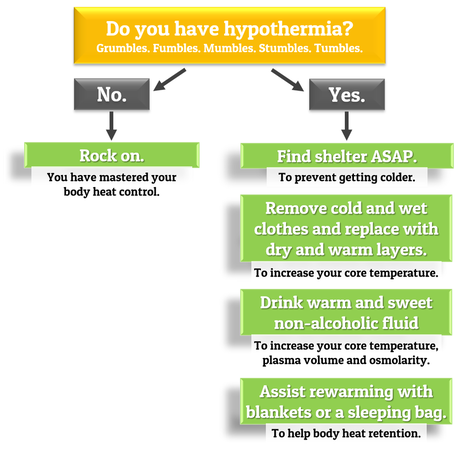

Grumbles - complaining or argumentative

Grumbles - complaining or argumentative

Fumbles - deteriorating hand-eye coordination

Fumbles - deteriorating hand-eye coordination

Mumbles -muttering and unclear speech

Mumbles -muttering and unclear speech

Stumbles - frequent tripping without reason

Stumbles - frequent tripping without reason

Tumbles -falling without obvious cause

Tumbles -falling without obvious cause

If the umbles are in full swing, do not ignore the signs — you are succumbing to hypothermia. Telling yourself to “man-up” is not useful because it will not warm you up. The best way to help yourself is to get away from the cold conditions and find shelter ideally in a warm and dry environment ASAP and begin warming up your body. At an air temperature of 5°C, heat loss in wet clothes is double that in dry conditions. So, if you are wet, follow Nelly’s advice and “take off all your clothes”, then bundle yourself in dry clothing and blankets to start warming yourself up. Shivering can be quite dramatic but it helps maintain core body temperature and is safe; just be prepared for it to take a long time to subside, even up to an hour.

If the umbles are in full swing, do not ignore the signs — you are succumbing to hypothermia. Telling yourself to “man-up” is not useful because it will not warm you up. The best way to help yourself is to get away from the cold conditions and find shelter ideally in a warm and dry environment ASAP and begin warming up your body. At an air temperature of 5°C, heat loss in wet clothes is double that in dry conditions. So, if you are wet, follow Nelly’s advice and “take off all your clothes”, then bundle yourself in dry clothing and blankets to start warming yourself up. Shivering can be quite dramatic but it helps maintain core body temperature and is safe; just be prepared for it to take a long time to subside, even up to an hour.

If someone you are with is experiencing hypothermia, take charge of the situation. Keep them interactive, explain what you want them to do, find out if they have any medical conditions and prevent any loss of consciousness. In the worst-case scenario, if someone does become unconscious, stay calm, place them in the recovery position, check for signs (airway, breathing, circulation; ABC), call for emergency help, keep them warm, and administer CPR (if required).

If someone you are with is experiencing hypothermia, take charge of the situation. Keep them interactive, explain what you want them to do, find out if they have any medical conditions and prevent any loss of consciousness. In the worst-case scenario, if someone does become unconscious, stay calm, place them in the recovery position, check for signs (airway, breathing, circulation; ABC), call for emergency help, keep them warm, and administer CPR (if required).

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Thanks for joining me on this chilly session. Stay tuned for the final part of this series in which I will delve into what you can do to condition yourself to be resilient to the cold. In the meantime, keep active, stay warm, and keep training smart!

Learning to recognize changes in weather conditions will help alert you to necessary changes in your plans that will reduce cold exposure and reduce the risk of cold injuries. Hypothermia most often develops when you are not prepared for it. If you think things are bad, they will likely get worse. Unexpected rain and/or wind, or unexpected and/or colder-than-expected water immersion can come as a shock and remove large amounts of body heat. As I explained in Part 1, body heat loss is much greater in cold, wet, and windy conditions, and if exercise intensity is not high enough to offset body heat loss, this is when the risk of developing hypothermia is greatest. Therefore, continually reevaluate as more input information becomes available.

As a guide, you can commit to memory a risk management checklist, some of which is adapted from the American College of Sports Medicine’s position stand on the prevention of cold injuries during exercise:

What is the air temperature where you are? What is the expected air temperature where you will go (e.g. altitude)? What is the humidity? What is the wind speed? What will be the level of natural shelter? For current weather updates check your local Met Office webpage.

Are wind, rain, snow, and/or water immersion possible? Know how the expected weather will affect the terrain, e.g. mudslides, wet rocks, avalanches, impassable rivers, strong winds on exposed ridgelines, etc. I was removed from a racecourse and taken to hospital with hypothermia in 2018 when the mid-race temperature abruptly plummeted from +5oC to -5oC as the beast from the east hit the British Isles. This mercury drop combined with high winds, snow, water immersion, and inadequate clothing for the unexpected weather, led to a night of cardiac monitoring and warm soup.

The time of day. Your level of fitness. Your level of fatigue from prior sessions. Your experience. Your general health. Your body size and/or body fat level. The planned exercise intensity and duration. Your feeding and hydration status. The availability of shelter. Standing still - if you are at a race and are forced to stand around before the start or after you have finished, find something to stand on in addition to boots and socks to insulate your feet from the frozen ground - cardboard, foam, or carpet scraps; a trick I have picked up from Austrians standing at ski or bobsleigh events. Water immersion - during an OCR race, do your utmost to keep your head, neck, and shoulders out of the water. If you are able to wade, keep your hands and arms out of the water. Loss of dexterity in your hands will not only prevent you completing rigs and climbing ropes in an OCR race but will also prevent you opening drinks bottles and food packets thus limiting your hydration status and fuel supply to keep you working at a high intensity and generating heat.

Plan your route – if you are in an unfamiliar area, use local resources or web resources to check the routes and conditions. Lots of offline maps are available for download so you can set your smartphone to low power mode and flight mode to preserve battery life. My favourite offline trail resource is the maps.me app. Tell someone where you’re headed, how long you will be, who is with you, what supplies you have, and what your ETA is. Take supplies but don’t overload – food, fluid, phone, spare clothing, contact numbers, head torch. Obtain accurate weather reports. Use an appropriate feeding and hydration strategy. Use proper clothing and equipment, and plan clothing changes if required. Plan shelter for re-warming at the end.

Conduct self-checks: ask yourself, “How do I feel? Am I still OK?”. Conduct buddy-checks if you’re with others. Evaluate the changing conditions. Be sensible, know your limits, and abort mission when necessary. Yes, adventure is the goal but know when it is time to stop, seek shelter, and turn back. My wife and I recently aborted a summit on Mount Taranaki when we emerged onto an exposed ridgeline where fog had set in, the rain was lashing down, and the wind speed was knocking us off our feet. Equipped with waterproof gear and good sense, we turned back and all we needed was a little hot chocolate to warm back up.

×

![]()

Optimise the factors that you can control.

Exposure to cold air temperatures, wind, and precipitation is a fact of life during winter training. But your cold-weather training does not have to be thwarted by the elements or moved indoors. The key to winter training is to stay safe and remain warm and dry. Maintaining whole-body or limb-specific thermal balance to maintain exercise performance in cold conditions is tricky. But, with the power of knowledge, you will be able to maintain normal core temperature and maintain adequate circulation in your skin and extremities and thereby prevent hypothermia. And, prevention is always better than treatment.No matter how many times weather forecasters will try to convince us, looking into the future is not an accurate endeavour and the weather is out of our control. In Part 1, I alluded to some of the “controllable” factors that can exploit to help mitigate your risk of hypothermia. These include your energy status and clothing choices.

You are in control of your energy status.

As described in Part 1, food restriction, such as an overnight fast, followed by high-intensity and/or long-duration exercise can cause your blood glucose to fall below normal levels (aka hypoglycaemia) which directly impairs your ability to shiver. Similarly, when your muscle glycogen levels (your cellular stores of glucose) are low, this also impairs your ability to maintain heat production during exercise in the cold and delays the onset of shivering. Therefore, both low blood glucose levels and low muscle glycogen levels remove your defence against heat loss, increasing the risk of hypothermia. Before stepping out of the door for any exercise in cold conditions, always ensure that you are adequately fed and if you plan on being out there for a prolonged period of time plan your nutrition and hydration needs. (Note → check out my series of articles on training nutrition, performance nutrition, and hydration to dive deep into these topics.)If you can maintain normal core body temperature, cold exposure during exercise does not directly increase oxygen consumption (and therefore caloric requirements) above normal, even in windy conditions. However, it is important to remember that you are still likely to expend slightly more energy during exercise in the cold. This is because your effort level through snow or mud is greater and because you may be carrying more load, like heavier clothing and backpacks for spare food and clothing. You will also expend more energy if you start shivering, but the intention of this series of articles is for you never to get to that point.

Maintaining blood glucose levels within the normal range while maximising muscle glycogen stores will help prevent hypothermia. These physiological goals will also prolong the duration at which you can maintain high-intensity exercise under all conditions. Therefore, it is sensible to include carbohydrates in your diet if you are an athlete seeking to maximise your performance outcome. If you are able to maintain your core and/or muscle temperature, fatigue is most often related to carbohydrate availability rather than thermoregulatory limitations and exercise can be sustained by ingesting carbohydrate in cold conditions. Because maintaining carbohydrate availability is key, it has been shown that maximizing muscle glycogen with carbohydrate loading before exercise in the cold is beneficial.

What can you do to help optimise your energy status?

To prevent a drop in blood glucose levels during a long-duration and/or high-intensity activity, take carbohydrate-containing foods with you, foods that suit your tastes and practicalities of the session/race. These will provide a glucose source to fuel your activity and spare muscle glycogen while also providing a thermic effect to help keep you warm. You might choose energy products like bars, gels, and drinks, but you may also opt for carbohydrate-rich foods like crackers, cereals, or bread.

Exercise in the cold initially increases core temperature and causes sweating.

Sweat rate is increased if exercise is at a high-intensity and/or while carrying load. If sweat rates during exercise exceed fluid intake, body water loss will occur and the risk of dehydration increases. Dehydration severely impairs exercise performance in temperate and hot environments. On the contrary, dehydration does not impair the onset of shivering or increase your risk of hypothermia directly, so, moderate fluid loss is less of a concern in the winter and dehydration has been shown to have less of an effect on exercise performance in the cold when compared hot environments. However, poor clothing choices can lead to overheating and high sweat rates, in which case hydration becomes paramount. (Note → you dive deep on this in my article on sweat.)What can you do to help optimise your hydration status?

I have learned not to rely on en route water taps in the winter as they are often turned off. But, generally, learning to monitor your hydration is wise so as to optimise performance year-round. To do this during exercise, keep it simple: drink to thirst. Meanwhile, monitoring your daily hydration status is covered in detail in a separate article but you can get started by saying “W U T?” , which provides a useful indication of hydration status in healthy active folks. What? Your daily hydration status can easily be determined by daily tracking of your morning body Weight, Urine colour, and feeling of Thirst. So,to assess your daily hydration status, every morning ask yourself 3 simple questions:

×

![]()

You are in control of your clothing choices.

There is no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing. This is a somewhat reductionist mantra, but it gets the point across. Clothing does not produce heat, it retains heat produced by your body. It provides insulation directly and indirectly by trapping air within and between layers, thereby reducing the risk of hypothermia and cold injuries to your skin. But your clothing requirements during exercise will change based on the ambient temperature and exercise intensity. As your intensity increases, the amount of clothing needed to maintain your body temperature will decrease at any given air temperature. Also, always remember that your risk of hypothermia increases if it is wet out there and your exercise intensity is low. So, staying dry is extremely important. However, it is not possible to state exactly what you should wear, even if you are in the same conditions. Your fitness, your exercise intensity, your sweat rate, your body size, and your energy status will each affect your ability to produce heat. So, continually practice and perfect your clothing choices, learn, and adapt to your own needs, with the goal of staying warm and dry and minimising sweat build up.What can you do to help optimise your clothing choices?

Cotton is rubbish. When it is wet, cotton retains water, gets heavy, is abrasive, and cools you down fast. I spent my teenage years training in Pearl Jam t-shirts and retro-style event t-shirts. My teenage grunge image was haunted by many a bloody nipple and numerous shivering, bollock-freezing moments. Ditch the “old school” t-shirts but keep listening to Pearl Jam.

Wool is ace. It wicks moisture, is insulative, and, when wet, stays insulative. Use wool base layers and mid layers on your extremities, your torso, your head, and your baby-making bits. Yes, Merino wool products can be expensive but I have never regretted wearing them and there are high-quality, low-cost options around, like the Mountain Warehouse own-brand products, which I have used successfully for several years.

Windproof, waterproof, and breathable, Gore-Tex and similar compounds, like Pertex, have combined these important facets into a single material and are an essential addition to your clothing arsenal. Such fabrics are expensive but I have learned from much trial and error that they are worth the investment - some things are just not worth scrimping on.

The aim is to be warm but not excessively sweaty, which will promote heat loss. Layering provides a flexible way to adjust your clothing on the fly to prevent overheating and sweating so as to remain dry. Also aim to avoid bulkiness, which can slow you down and/or cause pressure points that reduce circulation. Typical cold-weather clothing consists of three layers:

I couldn’t resist dropping one of my favourite German words: Handschuhe. Gloves are essential and will help maintain warmth and dexterity. Using a layering system similar to your normal clothing is very sensible. I have had a lot of success training in the winter with a thin merino glove liner (base) under a heavier wool glove (middle) under a Gore-Tex mitten (outer). The layering is easy to change on the fly. But, like all clothing approaches, do not wait until your hands are cold to put gloves on. Also, as a word of warning, do not blow warm breath into your hand-shoes because the vapour in your breath will add moisture to the glove which will contribute to further cooling, especially if it freezes.

When you stop moving, your body temperature will drop more rapidly in cold conditions. So, if you stop for food or water, or just for some banter, put on a layer.

When you step out that door, if you start with too many layers you will overheat and sweat. You’ll stop to take off a layer but, because you are wet underneath, then you’ll cool down rapidly and get cold. The solution, leave the house wearing fewer layers and take a pack with extra clothes. To look like a pro, many big name brands make packs of varying sizes that are useful for carrying gear, but they can be expensive. More pocket-friendly options can be found at Decathlon which stocks affordable and good-quality trail running backpacks made by Kalenji and trail running tights that have several zippered pockets for carrying gear.

At rest, muscle provides insulation during cold-water immersion but during exercise blood flow increases and the muscle’s insulative property is lost. Using clothing to cover and insulate active muscle is, therefore, very sensible if your race in is cold conditions and will include water immersion.

If the air is cold and dry, exercise can increase the risk of cold-induced bronchoconstriction even if you are healthy. One little trick to helping prevent and remedy this is to wrap a scarf or a buff loosely over your mouth and nose, not so tight that it impedes your breathing but just enough to humidify your breath.

In races that require frequent and/or prolonged water immersion, using neoprene clothing or even a full neoprene wetsuit is sensible and popular and within the rules of most OCR events. Note: as people involved in OCR will know, as of 2020 there is no current universal rule book that governs all races, so check the rules of your event. If the water immersion section requires swimming, neoprene increases core temperature, reduces drag, increases buoyancy and lowers oxygen consumption at a given speed. This is advantageous and in OCR races not yet deemed an unfair performance enhancement. Even without a full wetsuit, neoprene clothing like gloves, rash vests, arm sleeves, and head caps are also useful for maintaining limb-specific thermal balance and limiting heat loss. Protecting the head is particularly important since heat loss from your noggin can be as high as 50% of your total heat production when sitting at -4oC (25oF). A neoprene cap is easy to take on and off and wearing a wool liner under a neoprene cap has consistently proven to be a very useful way to combat mid-race cold water immersion.

You are in control of your footwear choices.

Footwear forms an important part of your clothing choices because your feet need to stay warm and dry. Admittedly that is sometimes very difficult, especially if there are water immersion components of your race - this is particularly pertinent to cross-country races, trail races, and obstacle races.What can you do to help optimise your footwear choices?

Cotton is a no go - it holds moisture, becomes heavy, and is abrasive when wet. Merino wool socks are a great choice for warmth and fast-drying properties but, as always, it is a matter of personal choice and comfort is a priority. So, try several different types in wet and cold conditions and stick to what works for you. But, take note, don’t double up on socks or wear socks that are too tight - this will restrict adequate blood flow - and remember that thicker socks will require a slightly larger shoe to accommodate them. Also remember that your feet will still sweat in the cold, particularly in heavy boots. A build-up of moisture around your feet for prolonged periods will increase the risk of trench foot. So, if you plan to be out there working hard for several hours in cold and/or wet conditions, always bring one or two changes of socks.

As for shoes, again you can pick all sorts of brands and models, some are even made with Gore Tex in the uppers but it is again a matter of personal choice. Two important lines of thought when choosing a winter shoe are “water drainage”, i.e. shoes need to empty water quickly once dunked and not be sponge-like, and “grip”. Personally, I have never found GoreTex in running shoes to be particularly useful - it adds extra weight and only protects you from incoming moisture that does not rise above the ankle, which in winter is almost never. Slipping, however, is a big issue because not only will it lose you time and places in a race but it can also cause serious injury and even be fatal in the mountains. There is no single shoe that will tackle every type of terrain but there are some shoe companies like Inov8 and VJ Sports that have invested large amounts of time into the soles of their shoes and use a variety of rubbers to help with wet rocks and even ice studs to help in snowy/icy conditions. Other brands like Hoka have partnered with Vibram to provide grippy soles. Again, personal comfort trumps any recommendation, so try some out. Many trail running stores have “try out” days where brands host days where you can borrow a pair of shoes for the day and destroy them on the trails at no cost or hidden agenda to have to purchase - this is a great way to decide which shoe might work for you. If you live in particularly icy conditions, I have had great success when living in Denmark, the US, Austria, and the UK, using Yaktrax attached to the outside of my shoes. In very snowy conditions, as I experienced in the midwest of Ohio and here in Austria, I use snowshoes for a lot of my winter running to great effect. Whatever you choose to put on your feet, side with comfort, and don’t lace too tightly - in a race, your metatarsal companions will be strapped to your feet for many hours, so form a friendly symbiotic relationship with them.

Photo: Davide Ligabue on Unsplash.

×

![]()

What to do if you take a turn to the dark side of winter?

In 2019, I spent six weeks, hiking, climbing, and running in the mountains of New Zealand. One of the many things that impressed me about that great country was how on top of outdoor safety the government was. It was not uncommon to be greeted at a trailhead by a park ranger warning of the current and predicted conditions, as well as signs along the way reminding you to conduct “self checks” and how to respond to certain dangers. There are also incredible resources and online courses easily and freely available to help learn a little more about staying safe outdoors. One poignant memory from those six weeks was the Mountain Safety Council's description of the “signs of hypothermia”, aka the -umbles.

×

![]()

Go and enjoy the winter!

Exercising in the cold does not increase musculoskeletal injury risk if you train safe. Nor does being in the cold necessarily mean that you will be cold. A cold environment does not need to be a barrier against effective exercise training or even against physically-active habits of daily living. Understanding the cold will help you make good decisions and making good decisions is the essence of reaching your genetic potential. So, know the weather conditions (i.e. temperature, humidity, and wind speed), understand what you can do to mitigate the risks induced by such conditions, know whether you or others are at greater risk in cold-weather environments, have a plan in place for dealing with a sudden change in conditions (i.e. abort mission and find shelter), and ensure you have immediate access to “re-warming” facilities when you finish your session. And, if your races might occur during cold conditions, training in cold conditions will help you learn which approaches work for you — practice your craft by aiming to get outdoors for as many of your sessions as possible.Thanks for joining me on this chilly session. Stay tuned for the final part of this series in which I will delve into what you can do to condition yourself to be resilient to the cold. In the meantime, keep active, stay warm, and keep training smart!

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.