Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery for runners and endurance athletes.

→ Part 1 — Eat, sleep, rest, repeat.→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery nutrition for runners and endurance athletes starts with a healthy eating pattern.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

8th Aug 2020.

If you’ve been following this series on recovery, you now know how to sleep and rest to get yourself ready to go again. But, you also need to eat well. Nutrition for recovery includes daily intake of everything the body needs while consuming adequate amounts of specific nutrients in between sessions to prepare you for the subsequent session. Today, I begin our run along the nutritional trails by examining the primary nutritional tool for an athlete: a healthy eating pattern...

Reading time ~25-mins

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Nutrition is a fascinating topic. It has a scientific basis combined with melodramatic undertones. What are my credentials for speaking with authority on this topic? Well, I have been consuming meals and making decisions about meal size and timing since the day I was born. My expertise was then cemented when, at the age of 1, I weaned onto solid food and the veritable smorgasbord of culinary opportunity ensued. That’s 40 years of experience in the field.

I am not alone. There are currently around 7-billion people on Earth who will one day have similar experience and, according to what I witness on social media, many will claim expertise in the topic and parade as practitioners prescribing all manner of dietary practices. Open discussions and idea-sharing on any topic is a fruitful endeavour. Discussing nutrition, like any topic, helps us understand different views. The problem with nutrition is that the points of view discussed sit on a continuum from fact to fiction. Unfortunately, the fictional social media storybooks unfold with vastly greater popularity than the facts...

Besides my 40-year experience with eating food, I have acquired additional knowledge along my journey through culinary time. A degree in Biochemistry, a PhD in Exercise Science, ACSM accreditations in Exercise Physiology (ACSM-EP) and Personal Training (ACSM-PT), and nutritionist registration (RNutr) with the Association for Nutrition. More importantly, I have nearly 20-years of experience in diet and exercise research and practice. And, the learning never ends - I take pride in continuing education - every day is a school day. So, what have I learned on this journey?

Whether you follow the practice of “not fussing and simply relying on autoregulation to intuitively get you through your nutritional life”, or whether you make conscious nutritional decisions based on either personal choices (vegetarianism/veganism), religious beliefs (food exclusion or Ramadan fasting), or genetic conditions (e.g. phenylketonuria) and immunological diseases (e.g. Coeliac disease), the human body has basic needs that can and should be addressed with a healthy eating pattern. There are no short-cuts - you cannot biohack basic biological necessity. The goal of a healthy eating pattern is to eat well, but what on Earth does that mean?

It is always important to remember that you are the only you, but the essence of human biology is the same in all of us. In relation to optimising your recovery from exercise and your return to performance, before worrying about the nuances of your diet, first become a master of what the human body needs to survive, grow, and stay healthy; and learn to understand how your daily demands affect those needs.

Wherever you live in the world, your government will update its healthy eating guidelines every few years. In the US, these guidelines are rather boringly-named the Dietary Guidelines, which have been developed into the excellent Choose My Plate tool. Australia has their Eat for Health guide, while the UK has the similarly named Eatwell Guide, which is presented in a user-friendly image and is clearly summarised by the British Nutrition Foundation. There are some nuances in the precise guidelines and recommended daily amounts (RDAs) between countries (click here for the various Food-based dietary guidelines within the United Nations) but the overall goal is identical - to achieve healthy eating.

Now, I am not going to provide you with number targets and meal-plans because they can be looked up and stressed over if you wish. Specific grams, milligrams, and micrograms of various nutrients are useful in the right hands (see my nutrition reference tables if you are inclined) but, off the top of your head, do you really know how to obtain 30 grams of fibre per day, 1000 mg of calcium, or even 2.4 μgrams of vitamin B12? Some nutrient needs also change with age and physiological states, like pregnancy. Even your religious beliefs or personal dietary choices may change over time. You might even have or develop a disease that dictates a nutrient exclusion. No matter what your needs are, it is important to remember that there is more than one way to achieve a healthy eating pattern. Your healthy eating pattern must be bespoke to your socio-cultural and/or personal preferences. That said, there are some basic rules of engagement based on what the human body needs to keep firing like a well-tuned engine…

The first important bite of knowledge to arm yourself with every time you make a nutritional choice, is that

healthy eating focuses on including a variety of nutrient-dense foods - foods with multiple vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, healthy fats, and lean proteins - while limiting “empty calories” - foods with just a single nutrient.

healthy eating focuses on including a variety of nutrient-dense foods - foods with multiple vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, healthy fats, and lean proteins - while limiting “empty calories” - foods with just a single nutrient.

The second morsel of knowledge is that

a healthy eating pattern limits the intake of sugar, saturated fat, trans-fats, salt (sodium), and alcohol - but that is rather dull because you already knew that. (Note here that high training loads or specific environments sometimes warrant extra intake of sugar and sodium… read on).

a healthy eating pattern limits the intake of sugar, saturated fat, trans-fats, salt (sodium), and alcohol - but that is rather dull because you already knew that. (Note here that high training loads or specific environments sometimes warrant extra intake of sugar and sodium… read on).

To achieve these healthy eating goals, your healthy eating pattern should include:

vegetables of all colours - dark green, red and orange - plus legumes (beans and peas) and starchy veg,

vegetables of all colours - dark green, red and orange - plus legumes (beans and peas) and starchy veg,

fruits of all colours, especially whole fruits rather than sugar-added fruit juice,

fruits of all colours, especially whole fruits rather than sugar-added fruit juice,

grains, especially whole grains (whole-wheat bread, whole-grain cereals and crackers, oatmeal, quinoa, popcorn, brown rice),

grains, especially whole grains (whole-wheat bread, whole-grain cereals and crackers, oatmeal, quinoa, popcorn, brown rice),

oils, especially unsaturated oils and spreads,

oils, especially unsaturated oils and spreads,

protein-containing foods, including seafood and oily fish, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes, and nuts, seeds, and soy products (like tofu),

protein-containing foods, including seafood and oily fish, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes, and nuts, seeds, and soy products (like tofu),

low-fat dairy (including milk, yoghurt, and cheese), and/or soy beverages (fortified with calcium), and

low-fat dairy (including milk, yoghurt, and cheese), and/or soy beverages (fortified with calcium), and

fluid, ideally with low-/no-sugar beverages.

fluid, ideally with low-/no-sugar beverages.

You might also wonder how much food you should eat… Well, it is neither possible nor appropriate to give a single numeric answer to that question. The bottom line is that your daily caloric intake must be sufficient in relation to your daily training load to maintain an adequate “energy availability” that allows your body to maintain normal physiological functions. For athletes, this typically also involves maintaining a healthy and stable body weight (noting of course that for some sports there may be times when weight gain or weight loss is appropriate depending on the time of season or performance goals). As a runner, always keep in mind that being light does not equal being fast, so a constant quest for weight loss is rarely appropriate and body weight must always be considered in the context of your power to weight ratio. NOTE: Energy availability and its relevance to the female athlete triad and reduced energy availability in sport (RED-S, which affects men and women), is a massively important concept that I will discuss in a forthcoming post.

So, as an athlete, healthy eating is achieved by eating a range of whole foods in adequate amounts relative to your needs. The goal for healthy eating is not achieved by a crash diet, sudden food exclusions, or stocking up on a whole array of supplements. The goal is to understand what healthy eating is and then to adopt such practices for the rest of your life - just like your training stimuli, nutritional consistency is key, so take meals seriously.

Poor eating habits are the biggest risk factor for nutritional deficiencies and a cause of body weight fluctuations. Understanding and implementing a healthy eating pattern will prevent you developing nutritional deficiencies and help you maintain body weight stability. You will be healthy. A healthy athlete is a high-performing athlete. An unhealthy athlete might produce pockets of brilliance but their form will gradually decline and they will never fulfil their genetic potential. So, healthy eating can give you the edge. But remember, just as you would when increasing your training load, if you are making changes to your nutritional habits, make gradual changes over time - help yourself adapt to new habits to make them a habit of daily living forever (and not just for a few weeks). And, if you do not know what you are doing, consult a Sports Nutritionist/Dietician.

Yum. A variety of whole foods.

Photo by Anna Pelzer on Unsplash.

Except for fibre, a type of indigestible carbohydrate that feeds your gut microbes and keeps your gastrointestinal system running smoothly, the food you eat is digested into small molecules that are absorbed into the blood and delivered to the different tissues. Carbohydrates (available carbohydrates, not fibre), fats, and proteins are digested into smaller molecules and then used in various processes or used to build new tissue. Carbohydrates and fats can also be stored in certain tissues: carbohydrate is stored as glycogen, primarily in muscles and liver, while fat is primarily stored in adipose tissue. In athletes, there is also an abundance of quickly-accessible fat droplets stored in muscle cells.

The main reason us humans eat food is to produce energy - the products of digestion are used inside the cells of all tissues to synthesize ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the chemical energy currency needed to drive the biochemical reactions taking place in the body. These reactions allow us to be, think, and move. As an athlete, you will have days when you move more and will, therefore, require more food to keep the ATP currency flowing.

To produce ATP, your cells primarily use fatty acids, from digested fats, and glucose, from digested carbohydrates. Amino acids, from digested proteins, can also be used for ATP production but their contribution to producing this chemical energy is negligible and only becomes relevant during starvation and disease. Producing ATP is vastly complicated and requires a large number of enzymes, each one catalysing a specific biochemical reaction in a long chain of events. As an athlete, eating carbohydrate and fat-containing foods is essential, primarily for immediate energy production or to be stored for subsequent energy production.

Amino acids, the protein building blocks, are primarily used to repair and/or build the various proteins needed around the body. Some amino acids are used to build the actual enzymes that help catalyse the reactions that produce ATP in your mitochondria, while other amino acids are incorporated into structural or contractile proteins, like the contractile proteins in your muscles that help you move. Different proteins synthesize and degrade at different rates but the two processes of protein synthesis and protein breakdown are continuous and never take a break. For athletes, daily protein ingestion is essential to create a sufficient availability of amino acids that prevents protein breakdown outweighing protein synthesis. Daily protein ingestion is essential because you do not have a bodily amino acid store.

To keep all of the many thousands of biochemical reactions running smoothly, your body also needs a whole heap of “helpers” in the form of vitamins and minerals. Some of the “helpers” can be synthesised in your body (e.g. vitamin D when exposed to UV), others can even be stored (e.g. vitamin A), but most of them must be consumed daily. Because each “helper” has a different skill set, sufficient availabilities of vitamins, cofactors, and minerals are essential to keep your engine structurally sound and running smoothly.

Athletes need daily dietary sources of carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fluid. As I already described, the healthy eating checklist provides a simple framework for obtaining your needs. But let’s take a slightly more detailed look at what healthy eating provides and which foods can help achieve it:

Carbohydrates in their “starch” form (formerly known as complex carbs) are found in whole grains, potatoes, brown rice, fruits, and vegetables. An indigestible type of starch, called fibre, is also an essential component of the diet and is found in whole grains and fruit and veg. Carbohydrates also come in a “simple” sugar form, which is also found in fruit and veg and other foods including milk, white rice, white bread, table sugar, candy, and sports drinks/bars/gels, etc.

Carbohydrates in their “starch” form (formerly known as complex carbs) are found in whole grains, potatoes, brown rice, fruits, and vegetables. An indigestible type of starch, called fibre, is also an essential component of the diet and is found in whole grains and fruit and veg. Carbohydrates also come in a “simple” sugar form, which is also found in fruit and veg and other foods including milk, white rice, white bread, table sugar, candy, and sports drinks/bars/gels, etc.

Fats are found in animal-based foods like meat, seafood, and dairy, and plant-based foods like nuts, seeds, olives, and avocados. Some fat-containing foods are also a source of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Oils, including DHA and EPA (docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid), the “essential” omega-3 fatty acids that the body needs but cannot synthesise, are found in cold-water oily fish like tuna and salmon, and fish oils. Essential fatty acids are also found in nuts and seeds and commonly consumed plant-based oils like canola, corn, olive, peanut, safflower, soybean, and sunflower oils.

Fats are found in animal-based foods like meat, seafood, and dairy, and plant-based foods like nuts, seeds, olives, and avocados. Some fat-containing foods are also a source of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Oils, including DHA and EPA (docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid), the “essential” omega-3 fatty acids that the body needs but cannot synthesise, are found in cold-water oily fish like tuna and salmon, and fish oils. Essential fatty acids are also found in nuts and seeds and commonly consumed plant-based oils like canola, corn, olive, peanut, safflower, soybean, and sunflower oils.

Protein can be obtained from animal products like lean meats, poultry, fish, and dairy (eggs, milk, and yoghurt) but also plant sources like soy, tofu, quinoa, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Soy milk is a good moo-milk alternative since it contains similar amounts of protein per 100 mL, but check that it has been fortified with calcium, B12, and vitamin D (which are not added to all soy products). Other plant-based products sold as “milk” (like almond, rice, coconut, and hemp drinks), typically contain negligible amounts of protein, calcium, and vitamins - I call these, “dirty water”. If you abstain from suckling on the teat of bovinity, best choose soymilk.

Protein can be obtained from animal products like lean meats, poultry, fish, and dairy (eggs, milk, and yoghurt) but also plant sources like soy, tofu, quinoa, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Soy milk is a good moo-milk alternative since it contains similar amounts of protein per 100 mL, but check that it has been fortified with calcium, B12, and vitamin D (which are not added to all soy products). Other plant-based products sold as “milk” (like almond, rice, coconut, and hemp drinks), typically contain negligible amounts of protein, calcium, and vitamins - I call these, “dirty water”. If you abstain from suckling on the teat of bovinity, best choose soymilk.

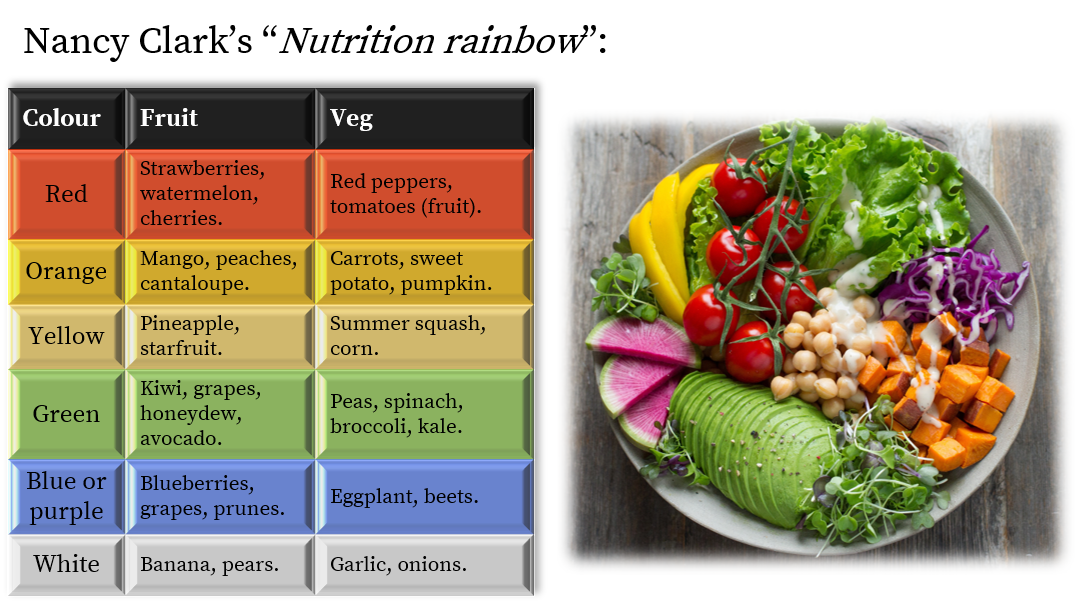

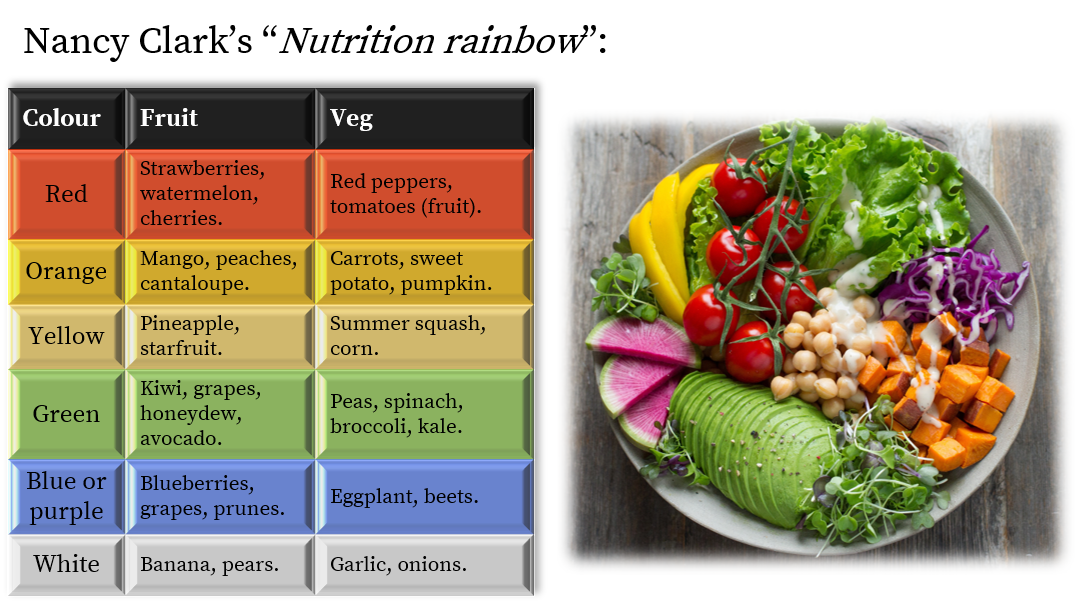

Vitamins are found in a wide range of foods. Fruit - when eaten from the range of colours - and vegetables - when chosen from all the subgroups (dark green, red and orange, beans and peas, starchy veg) - are a source of many vitamins (including vitamin A or beta-carotene, vitamin K, the antioxidant vitamins C and E, and the B-vitamins, B6, thiamin, niacin, and folate). Whole grains are a great source of vitamin A and the B-vitamins including B6, folate, thiamin, niacin, and riboflavin. Vitamin D, which is largely synthesised in the skin in the presence of sunlight, is found in oily fish, egg yolk, and fortified foods. Vitamin E is also found in nuts, seeds, seafood, olives, and avocados, and plant-based oils. Dairy products are also a good source of vitamins A, B12, riboflavin, and D, if fortified with it. Protein-containing foods like meat, eggs, legumes, nuts, and seeds, also provide a source of vitamins.

Vitamins are found in a wide range of foods. Fruit - when eaten from the range of colours - and vegetables - when chosen from all the subgroups (dark green, red and orange, beans and peas, starchy veg) - are a source of many vitamins (including vitamin A or beta-carotene, vitamin K, the antioxidant vitamins C and E, and the B-vitamins, B6, thiamin, niacin, and folate). Whole grains are a great source of vitamin A and the B-vitamins including B6, folate, thiamin, niacin, and riboflavin. Vitamin D, which is largely synthesised in the skin in the presence of sunlight, is found in oily fish, egg yolk, and fortified foods. Vitamin E is also found in nuts, seeds, seafood, olives, and avocados, and plant-based oils. Dairy products are also a good source of vitamins A, B12, riboflavin, and D, if fortified with it. Protein-containing foods like meat, eggs, legumes, nuts, and seeds, also provide a source of vitamins.

Minerals are also found in a variety of foods. For example, iron is found in meat, fish, and poultry, in its haem-bound form, which is more completely absorbed in the intestine than the plant-derived non-haem-bound form of iron, found in lentils, nuts, and dark green veg. Fruit (potassium) and veg (potassium, copper, magnesium, iron, and choline) provide a source of minerals, as do whole grains (iron, zinc, manganese, magnesium, copper, phosphorus, selenium), dairy products (calcium, phosphorus, potassium, zinc, choline, magnesium, and selenium), and protein foods like meat and eggs, legumes, nuts, and seeds (iron, selenium, choline, phosphorus, zinc, copper).

Minerals are also found in a variety of foods. For example, iron is found in meat, fish, and poultry, in its haem-bound form, which is more completely absorbed in the intestine than the plant-derived non-haem-bound form of iron, found in lentils, nuts, and dark green veg. Fruit (potassium) and veg (potassium, copper, magnesium, iron, and choline) provide a source of minerals, as do whole grains (iron, zinc, manganese, magnesium, copper, phosphorus, selenium), dairy products (calcium, phosphorus, potassium, zinc, choline, magnesium, and selenium), and protein foods like meat and eggs, legumes, nuts, and seeds (iron, selenium, choline, phosphorus, zinc, copper).

Fluid, of course, is best obtained by drinking water but is also in your other drinks, like tea and coffee, and beer and wine...

Fluid, of course, is best obtained by drinking water but is also in your other drinks, like tea and coffee, and beer and wine...

So, that’s a whirlwind tour through energy production and the necessity of carbs, fats, proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fluid. As you can see, the different food groups contain different types of nutrients and specific foods within the different food groups also contain different amounts of the above-described nutrients. Some foods are more “nutrient-dense” than others while other foods might not contain any of a particular nutrient. And, that is where the great puzzle begins… How do you know if you are consuming what you need?

My pint-sized wife recently ate a family-sized pizza.

Natural sources of whole foods are ideal for maintaining health and getting athletes ready to go again. This is why I have provided some food examples in this post. But don’t live and die by these examples as they are a learning tool not a life template. There is much to learn but start by learning to choose whole foods first and learning to eat a varied mix of whole foods every day - doing so will grace your fine body with all the nutrients it needs...

Yes, there are specific recommended daily intakes for most nutrients because a deficiency in a specific nutrient can cause disease. For example,

A lack of iron, which among many functions is required for haemoglobin your oxygen-carrying pigment in red blood cells, or a lack of B vitamins, which are required for carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, can cause anaemia, premature fatigue, and the inability to maintain training load.

A lack of iron, which among many functions is required for haemoglobin your oxygen-carrying pigment in red blood cells, or a lack of B vitamins, which are required for carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, can cause anaemia, premature fatigue, and the inability to maintain training load.

A lack of vitamin D, which is required for calcium absorption, and/or a lack of calcium, prevents adequate bone formation and turnover, allowing breaks and fractures to occur more easily.

A lack of vitamin D, which is required for calcium absorption, and/or a lack of calcium, prevents adequate bone formation and turnover, allowing breaks and fractures to occur more easily.

A lack of zinc, a structural and functional mineral that helps over 200 enzymes involved in energy metabolism (e.g. lactate dehydrogenase), DNA transcription, immunity and wound healing, or a lack of magnesium, a cofactor for over 300 enzymes involved in energy metabolism, muscle contraction (e.g. myosin-ATPase), glycogen breakdown, and protein synthesis, can cause muscle weakness, cramps, and muscle structural damage.

A lack of zinc, a structural and functional mineral that helps over 200 enzymes involved in energy metabolism (e.g. lactate dehydrogenase), DNA transcription, immunity and wound healing, or a lack of magnesium, a cofactor for over 300 enzymes involved in energy metabolism, muscle contraction (e.g. myosin-ATPase), glycogen breakdown, and protein synthesis, can cause muscle weakness, cramps, and muscle structural damage.

A lack of iron, vitamin D, zinc, and magnesium, along with other nutrients like vitamins A, E, and C, and the B-vitamins, including folic acid, can increase the risk of infection from bacterial or viral pathogens or prolong symptoms following an infection because they all play a role in white blood cell production or function. Since the immune system is also essential for wound healing, muscle repair, and training adaptations, such deficiencies can also delay recovery from injury and muscle soreness while blunting training adaptations.

A lack of iron, vitamin D, zinc, and magnesium, along with other nutrients like vitamins A, E, and C, and the B-vitamins, including folic acid, can increase the risk of infection from bacterial or viral pathogens or prolong symptoms following an infection because they all play a role in white blood cell production or function. Since the immune system is also essential for wound healing, muscle repair, and training adaptations, such deficiencies can also delay recovery from injury and muscle soreness while blunting training adaptations.

As an athlete, all this might sound a bit scary but do not mistake the “risk of deficiency” as an indication that you need to be popping pills and/or megadosing on such nutrients.

Aim for food rather than pills and powders.

If you have nutrient intake deficiencies because of dietary exclusions enforced by genetic conditions, religious beliefs, or personal choice, then supplements are often advised. Likewise, if you have blood test-confirmed deficiencies in nutrient biomarkers, like vitamin D or the iron-storage protein, ferritin, then certain supplements might also become part of your healthy eating practice. Either way, because supplementation can easily be eff dup and cause issues that didn’t previously exist, dietary supplementation should be implemented with guidance from your doctor and a qualified nutritionist/dietician. If you don’t know how to build a house, don’t start laying any bricks.

Why the scare tactic with dietary supplements? Well, for the sole reason that the world of supplements is, incredibly, very poorly-regulated. A naturally-occurring compound that can be extracted from food, does not kill humans, and is not marketed to treat or prevent disease, can be bottled and sold. Simple. If a compound is chemically-modified, it is then labelled as a drug and it typically takes at least 10-years to bring to market. Dietary supplements are marketed to the world via advertisements with the spin of bold promises like “healthy ageing” and “immune-boosting” and “performance-enhancing”. The problem being that evidence for the health benefits of dietary supplements in people without deficiencies is lacking, and as I alluded to above, if you do have a clinically-confirmed nutrient deficiency, seek qualified advice - ask yourself, “do you have the medical education to know what you are doing when browsing the aisles in your local supplement store?”.

My favourite example for the over-zealous world of supplement marketing is that of vitamin C. In the words of Eddie Izzard,

This might feel like I am embarking on a rant, but please stay with me a little longer as the nutritious punchline is approaching...

In some cases, with unwitting dietary supplementation, you can flirt the line between pointlessness and outright danger. You might cross this line with fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin A, D, or E, which become toxic in large doses, or with minerals that have a bodily store. A classic example is iron, which is required for many bodily functions including immunity, muscle contractions, and oxygen transport. As an athlete, some of those functions will sound most useful. Iron deficiency is not good for us humans as it can be a cause of anaemia and associated chronic fatigue. But excess iron intake is a mutually-dangerous sin that doesn’t require too much excessive intake and causes iron overload where excess iron is deposited in your tissues leading to heart failure, liver disease, and neurological decline. Again, I ask, do you know what you are doing when browsing the supplement aisles?

Please avoid megadosing and beware of any food supplement company trying to tell you otherwise. Dietary supplement use is widespread in athletes but megadosing vitamins and minerals (which studies show is common in athletes) will likely do more harm than good. Since vitamins are coenzymes, when the enzymes systems they are supporting become saturated, the vitamins freely circulate and can become toxic. This is especially true of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K). If you have a clinically-proven deficiency in a nutrient (like iron or vitamin D) then, yes, supplementation can be a useful tool to bring your levels back into the healthy reference range. As a human, but also as an athlete, it is your responsibility to learn, implement, and sustain healthy eating habits to ensure that you obtain all the nutrients you need to recover, adapt, and get ready to go again, time after time, in a healthy manner… Food first, supplements second.

Which one of these is good for scurvy? … a lime.

Photo by Adam Nieścioruk on Unsplash.

Exercise is indeed a powerful tool for maintaining health but athletes are not immune to the effects of a bad diet and/or increased nutrient loss. A deficiency in one or more nutrients over several days or weeks may impair your recovery and decrease your performance by reducing your ability to train (an effect of iron deficiency anaemia) or by increasing your risk of injury or illness (an effect of vitamin D and calcium deficiency). That said, adopting a healthy eating pattern reduces your risk of developing a nutrient deficiency.

A nice analogy to consider is the Formula 1 racing car. Team mechanics apply their graceful touches to the engine to keep it as fast and as economical as is required for the conditions of the track and the demands of the race. Feed the engine the wrong fuel, the engine fails, and all the hard work was futile... An athlete consuming a terrible diet will eventually find holes in their return to form. Fix the diet, optimise the recovery.

Compared to regular folk, an athlete’s engine is revving faster and for longer and needs to be well-tuned. Compared to regular folk, athletes’ nutritional requirements increase for some but not all nutrients. For example, when training load increases, total daily caloric intake must also increase because of the greater carbohydrate and fat utilisation during sessions and the greater need for protein to help repair, strengthen, and grow. Because more food must be eaten to meet the expense of the firing engine while leaving enough energy available for normal bodily function, it is often a natural extension that most nutrients are also consumed in greater amounts. For example, a study of 419 male and female international athletes found that daily intakes of vitamins and minerals were positively associated with daily caloric intake - the more food athletes ate, the greater their micronutrient intake, and the further above the specific RDA values they rose.

Studies show that a healthy eating patterns and sufficient energy availability are not widespread in elite athletes, that macronutrient recommendations are often not achieved, and that inadequate dietary habits are associated with nutritional deficiencies. Naturally, there are also some situations where specific nutritional demands might increase. Excessive sweating, particularly when living or training in hot or humid environments, can increase daily requirements of some micronutrients including minerals like sodium, iron, zinc, and magnesium, while menstruation, regular blood donation or training at high altitude can increase the need for iron. But these are not necessarily indications that a supplement is needed - the increased requirement can be achieved with whole foods. That said, situations do exist where dietary supplements are indicated. For example, iodine is advised in people not consuming iodised salt or living in areas with low levels of iodine in foods. Folate is advised in women planning a pregnancy. And, vitamin B12 is advised in those who exclude meat in their diet - vegetarians/vegans - since it is not generally found in plants (with the exception of some algae that are not commonly eaten).

Since healthy eating patterns are not widespread, nutrient deficiencies can be rather common. According to a 2018 IOC Consensus Statement and evidence from other surveys, there are three classic deficiencies that athletes often present with:

Low ferritin (our bodily store of iron, which is toxic in excess);

Low ferritin (our bodily store of iron, which is toxic in excess);

Low calcium and/or bone mineral density; and

Low calcium and/or bone mineral density; and

Low vitamin D, which supports calcium absorption but is also toxic in excess and can cause exaggerated calcium deposition.

Low vitamin D, which supports calcium absorption but is also toxic in excess and can cause exaggerated calcium deposition.

Before your alarm bell starts ringing, it is exceptionally important to understand that this info is not a shopping list dictating which supplements you need to stock up on. I bring your attention to these facts so, as an athlete, you are aware of the demands your body is under and so you are armed with useful information to take to your GP to request some blood tests to rule out any deficiencies - this is the best approach if you are concerned about your nutrient intake or nutrient deficiencies. As an athlete, regular tests like this are advisable for maintaining health, preventing disease, and keeping your engine firing smoothly.

Over-the-counter dietary supplements are a supplement to, but not a replacement for, healthy eating patterns. Taking a self-prescribed daily nutritional supplement as an “insurance policy” might seem sensible but how do you know whether it is doing good, doing nothing, or causing harm? Clinical tests are highly-informative decision-making tools but they are not a replacement for being a master of your nutritional choices - implementing healthy eating habits can start today and will help prevent nutrient deficiencies arising before you head to your doctor. For example, iron needs can be met by eating meat, fish, and poultry, or plant sources like lentils, nuts, and dark green veg; vitamin C, which increases the absorption of iron, can be found in oranges, lemons/limes, raspberries, and grapefruit; vitamin D can either be synthesised by exposure to UV (but lying in the sun is not particularly healthy) or by eating oily fish (salmon/tuna), egg yolk, or foods fortified with vitamin D; and calcium can be consumed in dairy or fortified soymilk.

To help stay calm and on track, use this simple but effective logical strategy:

Your healthy eating pattern should be sustainable every day. As an athlete, you are very likely to be travelling a lot, for races or even just for training. Being in new and unfamiliar environments can throw a spanner in the works. Planning your nutritional travel strategy ahead of time will keep you calm and well fed:

Identify food access at your destination - supermarkets, restaurants - and consider your arrival time;

Identify food access at your destination - supermarkets, restaurants - and consider your arrival time;

Bring supplemental food for the journey - water bottle, fruit, bars;

Bring supplemental food for the journey - water bottle, fruit, bars;

Stay hydrated during flights - drink fluids regularly, to thirst; and

Stay hydrated during flights - drink fluids regularly, to thirst; and

Check food safety standards at your destination - can you drink the tap water?

Check food safety standards at your destination - can you drink the tap water?

When travelling to the Spartan Race World Championships in Tahoe in 2018, I knew that grocery store access would be tough in the pricey ski resort of Squaw Valley, and I didn’t want to eat out prior to the race through risk of abruptly changing the foods that I (and my gut) were used to. So, I packed 5-days of food from the UK and this kept me on track, particularly during the journey and on arrival at 1 am when nothing was open. Excitingly, I was stopped for a luggage check in Denver, and had a fun time explaining to a grumpy and finger-on-the-trigger type of TSA officer why I had multiple tins of tuna, carrots, apples, bags of pasta, and two ziplock bags of white powder (maltodextrin) in my case. Excitement turned to fear. It was my worst US arrival to date - never smile at or crack jokes with Homeland Security. Amen.

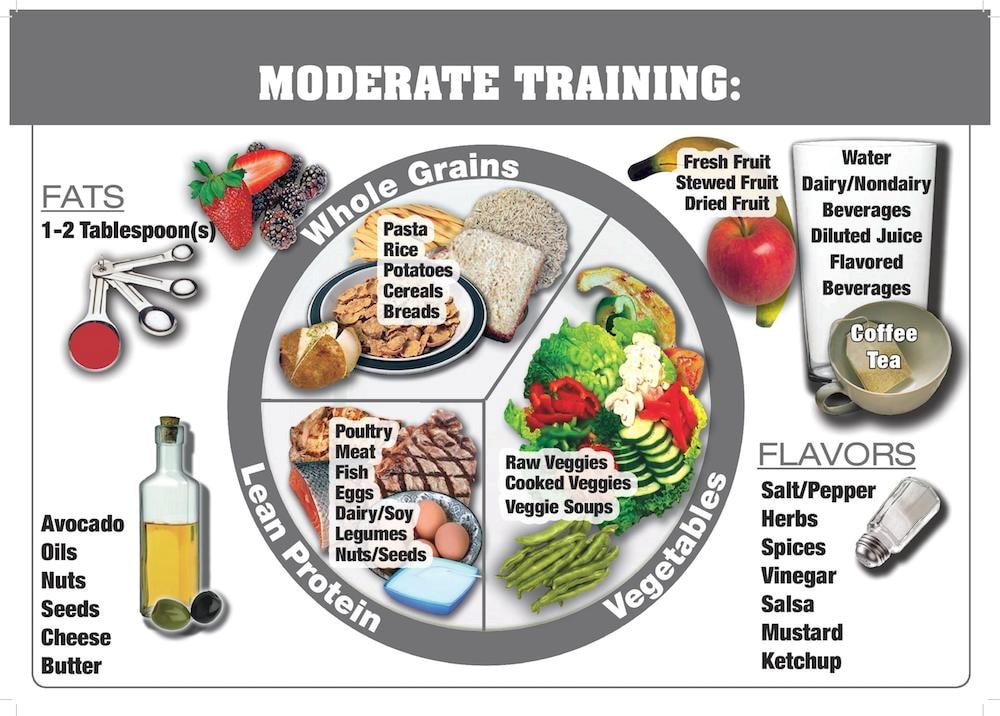

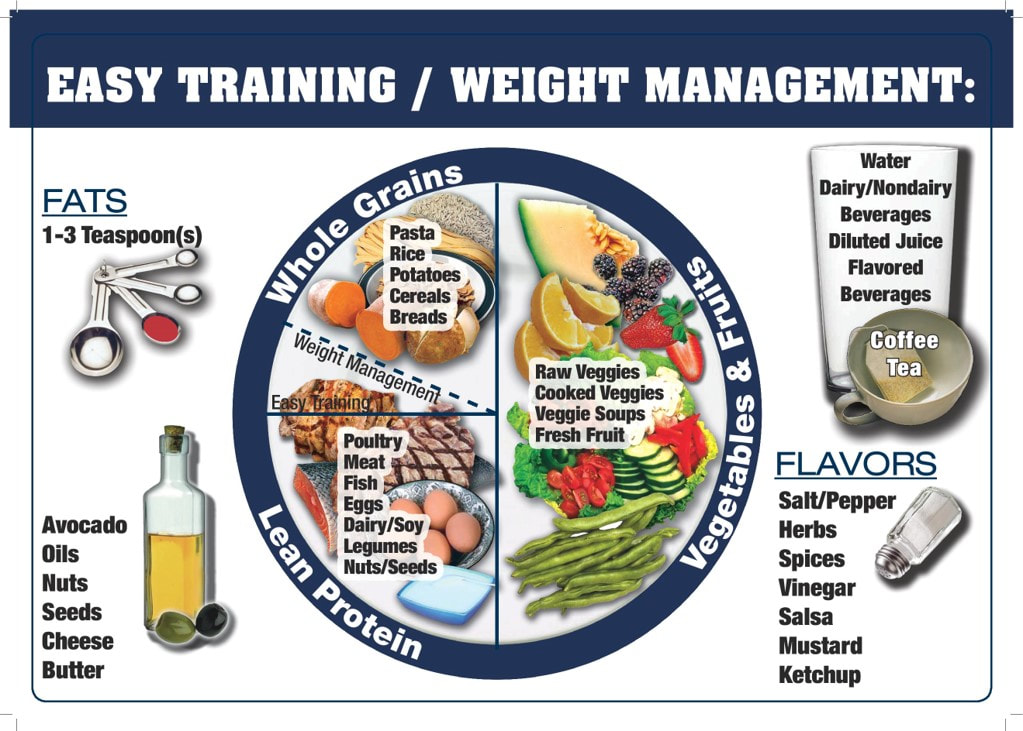

In the absence of being held in custody, to support your quest for a healthy eating pattern, a collaboration between the United States Olympic Committee Sport Dietitians and the University of Colorado (UCCS) Sport Nutrition Graduate Program developed “The Athlete’s Plates” (which were validated in 2019). The Athlete’s Plates provide a visual guide to help you learn what a variety of nutrient dense foods looks like. The birds-eye views of the easy-, moderate-, and hard-training plates show the relative areas that carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and fruit and veg should cover on your plate. Since your training load will vary from day-to-day and week-to-week depending on your training phase, eating to fuel your sessions (or races) and recover from them will depend on how hard your sessions are. So, the Athletes’ Plates provide useful visual clues as to how the relative amounts of the different food groups might vary in line with different daily training loads.

For example, “Moderate day meals” contain lean protein foods covering about a quarter of your plate, with the remaining three-quarters equally divided between whole-grain carbohydrate sources and vegetables. Moderate day meals are relevant on a moderate-effort training day that might include two sessions but with a focus on technical skill in one and endurance in the other. The moderate day is your baseline from where you adjust your plate down (for easy days) or up (for hard days or race days).

abundance and variety of whole foods, their

abundance and variety of whole foods, their

presence of all food groups, including lean protein, at every meal, and the

presence of all food groups, including lean protein, at every meal, and the

increasing contribution of carbohydrate-containing foods as training intensity increases from easy to moderate to hard.

increasing contribution of carbohydrate-containing foods as training intensity increases from easy to moderate to hard.

The Athletes’ Plates are a guide, not a rule. To help put healthy eating into practice, work with a registered sports nutritionist/dietician for the best outcome and for a deeper dive into the topic, the IAAF (now called World Athletics) published a consensus statement in 2019 on Nutrition for Athletics, headed by Professor Louise Burke.

A professional athlete not doing all they can to be the best they can be, is remarkably foolish. A builder never leaves out the foundations ahead of constructing their masterpiece. Ignoring nutrition and expecting to fulfil your genetic potential is a silly game that I suggest you avoid. So, to leave you with something to chew on, here are some nuggets to put in your recovery tool box:

Educate yourself with reputable “sauces” of info to help bolster your immunity to sexy-sounding marketing gimmicks and misleading advertising.

Educate yourself with reputable “sauces” of info to help bolster your immunity to sexy-sounding marketing gimmicks and misleading advertising.

Identify your barriers to healthy eating and create solutions to these challenges.

Identify your barriers to healthy eating and create solutions to these challenges.

Plan your meals and snacks so a healthy choice is always available.

Plan your meals and snacks so a healthy choice is always available.

Aim for consistency even when your environment changes.

Aim for consistency even when your environment changes.

Distribute your caloric intake evenly through the day, e.g. 3-meals + 2-snacks, rather than a 1- or 2- massive binges.

Distribute your caloric intake evenly through the day, e.g. 3-meals + 2-snacks, rather than a 1- or 2- massive binges.

Include nutrient-dense foods at every meal or snack opportunity.

Include nutrient-dense foods at every meal or snack opportunity.

Include all food groups, including protein, at every meal.

Include all food groups, including protein, at every meal.

Fresh fruits and veg, whole grains, beans, oils, nuts, seeds, lean protein, low-fat dairy or soy, are your friends.

Fresh fruits and veg, whole grains, beans, oils, nuts, seeds, lean protein, low-fat dairy or soy, are your friends.

Dietary supplements are useful when dietary deficiencies exist or when nutritional needs cannot be met, but only under medical guidance and consultation with a registered nutritionist/dietician. To help inform choices, use my Sports Supplement Tool.

And, most importantly:

Dietary supplements are useful when dietary deficiencies exist or when nutritional needs cannot be met, but only under medical guidance and consultation with a registered nutritionist/dietician. To help inform choices, use my Sports Supplement Tool.

And, most importantly:

eat read more digestible knowledge on the topic along with food ideas and recipes, I can highly-recommend adding Nancy Clark’s, Sports Nutrition Guidebook, to your bookshelf. Or, for a deeper but readable feast on the topic, check out Louise Burke’s book, Clinical Sports Nutrition... “Mange, mange, mange”, as my French twin would say...

I am not alone. There are currently around 7-billion people on Earth who will one day have similar experience and, according to what I witness on social media, many will claim expertise in the topic and parade as practitioners prescribing all manner of dietary practices. Open discussions and idea-sharing on any topic is a fruitful endeavour. Discussing nutrition, like any topic, helps us understand different views. The problem with nutrition is that the points of view discussed sit on a continuum from fact to fiction. Unfortunately, the fictional social media storybooks unfold with vastly greater popularity than the facts...

Besides my 40-year experience with eating food, I have acquired additional knowledge along my journey through culinary time. A degree in Biochemistry, a PhD in Exercise Science, ACSM accreditations in Exercise Physiology (ACSM-EP) and Personal Training (ACSM-PT), and nutritionist registration (RNutr) with the Association for Nutrition. More importantly, I have nearly 20-years of experience in diet and exercise research and practice. And, the learning never ends - I take pride in continuing education - every day is a school day. So, what have I learned on this journey?

Optimising your nutrition for recovery should begin with learning to “eat well” for the rest of your life.

As I begin to delve into recovery nutrition, I do not wish to encourage an obsession with eating “healthy” foods, a condition known as orthorexia. Neither will I dive into the conditions of disordered eating (which include unhealthy eating behaviours and body image concerns). Nor will I examine the complex biology of weight control. My aim when discussing the topic of nutrition for athletes is not to be a drill instructor dictating what you should eat but to help you learn what the body actually needs to help maintain healthy function using a food first approach. When it comes to exercise performance, as an athlete, your dietary needs alter in line with the demands of your sport but your body’s basic nutritional needs do not change. For athletes, just like regular folk, I also advocate a food first approach.Whether you follow the practice of “not fussing and simply relying on autoregulation to intuitively get you through your nutritional life”, or whether you make conscious nutritional decisions based on either personal choices (vegetarianism/veganism), religious beliefs (food exclusion or Ramadan fasting), or genetic conditions (e.g. phenylketonuria) and immunological diseases (e.g. Coeliac disease), the human body has basic needs that can and should be addressed with a healthy eating pattern. There are no short-cuts - you cannot biohack basic biological necessity. The goal of a healthy eating pattern is to eat well, but what on Earth does that mean?

What is a healthy eating pattern?

When David Epstein wrote about embracing range and how that may lead to greater success in the long term, he focused on human performance as the prime example. Nutrition is pretty similar. A healthy eating pattern is most easily illustrated by eating a range of whole foods - a variety of nutrient-dense foods of all colours across and within all food groups. By eating in this way you will consume carbohydrates (including fibre), fats, proteins, vitamins, and minerals.It is always important to remember that you are the only you, but the essence of human biology is the same in all of us. In relation to optimising your recovery from exercise and your return to performance, before worrying about the nuances of your diet, first become a master of what the human body needs to survive, grow, and stay healthy; and learn to understand how your daily demands affect those needs.

Wherever you live in the world, your government will update its healthy eating guidelines every few years. In the US, these guidelines are rather boringly-named the Dietary Guidelines, which have been developed into the excellent Choose My Plate tool. Australia has their Eat for Health guide, while the UK has the similarly named Eatwell Guide, which is presented in a user-friendly image and is clearly summarised by the British Nutrition Foundation. There are some nuances in the precise guidelines and recommended daily amounts (RDAs) between countries (click here for the various Food-based dietary guidelines within the United Nations) but the overall goal is identical - to achieve healthy eating.

Now, I am not going to provide you with number targets and meal-plans because they can be looked up and stressed over if you wish. Specific grams, milligrams, and micrograms of various nutrients are useful in the right hands (see my nutrition reference tables if you are inclined) but, off the top of your head, do you really know how to obtain 30 grams of fibre per day, 1000 mg of calcium, or even 2.4 μgrams of vitamin B12? Some nutrient needs also change with age and physiological states, like pregnancy. Even your religious beliefs or personal dietary choices may change over time. You might even have or develop a disease that dictates a nutrient exclusion. No matter what your needs are, it is important to remember that there is more than one way to achieve a healthy eating pattern. Your healthy eating pattern must be bespoke to your socio-cultural and/or personal preferences. That said, there are some basic rules of engagement based on what the human body needs to keep firing like a well-tuned engine…

The second morsel of knowledge is that

To achieve these healthy eating goals, your healthy eating pattern should include:

So, as an athlete, healthy eating is achieved by eating a range of whole foods in adequate amounts relative to your needs. The goal for healthy eating is not achieved by a crash diet, sudden food exclusions, or stocking up on a whole array of supplements. The goal is to understand what healthy eating is and then to adopt such practices for the rest of your life - just like your training stimuli, nutritional consistency is key, so take meals seriously.

Poor eating habits are the biggest risk factor for nutritional deficiencies and a cause of body weight fluctuations. Understanding and implementing a healthy eating pattern will prevent you developing nutritional deficiencies and help you maintain body weight stability. You will be healthy. A healthy athlete is a high-performing athlete. An unhealthy athlete might produce pockets of brilliance but their form will gradually decline and they will never fulfil their genetic potential. So, healthy eating can give you the edge. But remember, just as you would when increasing your training load, if you are making changes to your nutritional habits, make gradual changes over time - help yourself adapt to new habits to make them a habit of daily living forever (and not just for a few weeks). And, if you do not know what you are doing, consult a Sports Nutritionist/Dietician.

Photo by Anna Pelzer on Unsplash.

×

![]()

What will “healthy eating” provide you with?

Keeping things simple, your body needs macronutrients - carbohydrates, fats, and proteins - and micronutrients - vitamins and minerals in varying amounts. Healthy eating provides all these things...Except for fibre, a type of indigestible carbohydrate that feeds your gut microbes and keeps your gastrointestinal system running smoothly, the food you eat is digested into small molecules that are absorbed into the blood and delivered to the different tissues. Carbohydrates (available carbohydrates, not fibre), fats, and proteins are digested into smaller molecules and then used in various processes or used to build new tissue. Carbohydrates and fats can also be stored in certain tissues: carbohydrate is stored as glycogen, primarily in muscles and liver, while fat is primarily stored in adipose tissue. In athletes, there is also an abundance of quickly-accessible fat droplets stored in muscle cells.

The main reason us humans eat food is to produce energy - the products of digestion are used inside the cells of all tissues to synthesize ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the chemical energy currency needed to drive the biochemical reactions taking place in the body. These reactions allow us to be, think, and move. As an athlete, you will have days when you move more and will, therefore, require more food to keep the ATP currency flowing.

To produce ATP, your cells primarily use fatty acids, from digested fats, and glucose, from digested carbohydrates. Amino acids, from digested proteins, can also be used for ATP production but their contribution to producing this chemical energy is negligible and only becomes relevant during starvation and disease. Producing ATP is vastly complicated and requires a large number of enzymes, each one catalysing a specific biochemical reaction in a long chain of events. As an athlete, eating carbohydrate and fat-containing foods is essential, primarily for immediate energy production or to be stored for subsequent energy production.

Amino acids, the protein building blocks, are primarily used to repair and/or build the various proteins needed around the body. Some amino acids are used to build the actual enzymes that help catalyse the reactions that produce ATP in your mitochondria, while other amino acids are incorporated into structural or contractile proteins, like the contractile proteins in your muscles that help you move. Different proteins synthesize and degrade at different rates but the two processes of protein synthesis and protein breakdown are continuous and never take a break. For athletes, daily protein ingestion is essential to create a sufficient availability of amino acids that prevents protein breakdown outweighing protein synthesis. Daily protein ingestion is essential because you do not have a bodily amino acid store.

To keep all of the many thousands of biochemical reactions running smoothly, your body also needs a whole heap of “helpers” in the form of vitamins and minerals. Some of the “helpers” can be synthesised in your body (e.g. vitamin D when exposed to UV), others can even be stored (e.g. vitamin A), but most of them must be consumed daily. Because each “helper” has a different skill set, sufficient availabilities of vitamins, cofactors, and minerals are essential to keep your engine structurally sound and running smoothly.

Athletes need daily dietary sources of carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fluid. As I already described, the healthy eating checklist provides a simple framework for obtaining your needs. But let’s take a slightly more detailed look at what healthy eating provides and which foods can help achieve it:

Variety is key! But, keep it simple - food first, supplements second.

Healthy eating doesn’t need to be tackled like a giant puzzle. Don’t stress. Don’t overcomplicate things. Begin to educate yourself so you may bathe in the knowledge that you can fulfil all your dietary needs with the foods available in your grocery store. Educating yourself will also allow you to relax when you discover that your health is not destroyed if your healthy eating habits occasionally turn to the dark side for a day or two. You fancy eating a family-sized pizza? Eat a family-sized pizza, with toppings you like. Don’t worry about the calories or the macros, just eat a tasty pizza that makes your face smile and your belly bulge. Then, get back on track.

×

![]()

As an athlete, sometimes a sports bar, drink, or gel is necessary during training/competitions; sometimes, other supplemental foods, like a protein powder, might be an appropriate option. But your daily total nutritional needs should primarily be met using whole food sources - food first - dietary or sports supplements should not replace meals of real food - food first. Whole foods in their most natural, unprocessed form provide the body with the greatest variety and density of nutrients. And, they are darn tasty! So, incorporate as many whole foods as you can into your eating pattern to maximize the nutritional benefit. Food first.

Natural sources of whole foods are ideal for maintaining health and getting athletes ready to go again. This is why I have provided some food examples in this post. But don’t live and die by these examples as they are a learning tool not a life template. There is much to learn but start by learning to choose whole foods first and learning to eat a varied mix of whole foods every day - doing so will grace your fine body with all the nutrients it needs...

Yes, there are specific recommended daily intakes for most nutrients because a deficiency in a specific nutrient can cause disease. For example,

×

![]()

Why can’t you just take a dietary supplement?

Yes, studies show that nutrient deficiencies cause disease but the evidence also shows that consuming large nutrient doses that vastly exceed recommended daily intake guidelines do not confer additional benefits for general health or exercise adaptations. Naturally, there are of course exceptions to the rule…If you have nutrient intake deficiencies because of dietary exclusions enforced by genetic conditions, religious beliefs, or personal choice, then supplements are often advised. Likewise, if you have blood test-confirmed deficiencies in nutrient biomarkers, like vitamin D or the iron-storage protein, ferritin, then certain supplements might also become part of your healthy eating practice. Either way, because supplementation can easily be eff dup and cause issues that didn’t previously exist, dietary supplementation should be implemented with guidance from your doctor and a qualified nutritionist/dietician. If you don’t know how to build a house, don’t start laying any bricks.

Why the scare tactic with dietary supplements? Well, for the sole reason that the world of supplements is, incredibly, very poorly-regulated. A naturally-occurring compound that can be extracted from food, does not kill humans, and is not marketed to treat or prevent disease, can be bottled and sold. Simple. If a compound is chemically-modified, it is then labelled as a drug and it typically takes at least 10-years to bring to market. Dietary supplements are marketed to the world via advertisements with the spin of bold promises like “healthy ageing” and “immune-boosting” and “performance-enhancing”. The problem being that evidence for the health benefits of dietary supplements in people without deficiencies is lacking, and as I alluded to above, if you do have a clinically-confirmed nutrient deficiency, seek qualified advice - ask yourself, “do you have the medical education to know what you are doing when browsing the aisles in your local supplement store?”.

My favourite example for the over-zealous world of supplement marketing is that of vitamin C. In the words of Eddie Izzard,

“vitamin C is good for scurvy, isn’t it?

Yes! There’s a lot of scurvy around these days…”.

Granted, no one wants scurvy. The “limeys” ingeniously prevented it by eating lemons and limes. Vitamin C can easily be consumed in whole foods - an orange, a kiwi fruit, a cup of pineapple, or a cup of broccoli all contain enough vitamin C - about 100 milligrams - to meet your daily needs. Yet, a typical vitamin C tablet can contain anywhere from 400 to 3000 milligrams! I don’t particularly like acronyms but this is a massive case of WTF. Why do I say that...? Vitamin C is a water-soluble vitamin that cannot be stored in the body. Because of that property, if you consume more than is needed your body will quite literally flush the excess down the toilet. The good news for Vitamin C is that it is not toxic. So, in this case, megadosing is not harmful but pointless, especially when considering the systematic reviews and meta-analyses showing that vitamin C supplementation neither prevents nor treats the common cold, pneumonia, or SARS.

Yes! There’s a lot of scurvy around these days…”.

This might feel like I am embarking on a rant, but please stay with me a little longer as the nutritious punchline is approaching...

In some cases, with unwitting dietary supplementation, you can flirt the line between pointlessness and outright danger. You might cross this line with fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin A, D, or E, which become toxic in large doses, or with minerals that have a bodily store. A classic example is iron, which is required for many bodily functions including immunity, muscle contractions, and oxygen transport. As an athlete, some of those functions will sound most useful. Iron deficiency is not good for us humans as it can be a cause of anaemia and associated chronic fatigue. But excess iron intake is a mutually-dangerous sin that doesn’t require too much excessive intake and causes iron overload where excess iron is deposited in your tissues leading to heart failure, liver disease, and neurological decline. Again, I ask, do you know what you are doing when browsing the supplement aisles?

Please avoid megadosing and beware of any food supplement company trying to tell you otherwise. Dietary supplement use is widespread in athletes but megadosing vitamins and minerals (which studies show is common in athletes) will likely do more harm than good. Since vitamins are coenzymes, when the enzymes systems they are supporting become saturated, the vitamins freely circulate and can become toxic. This is especially true of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K). If you have a clinically-proven deficiency in a nutrient (like iron or vitamin D) then, yes, supplementation can be a useful tool to bring your levels back into the healthy reference range. As a human, but also as an athlete, it is your responsibility to learn, implement, and sustain healthy eating habits to ensure that you obtain all the nutrients you need to recover, adapt, and get ready to go again, time after time, in a healthy manner… Food first, supplements second.

Note: to help inform your choices about supplements, please see my

Sports Supplement Tool.

Sports Supplement Tool.

Photo by Adam Nieścioruk on Unsplash.

×

![]()

Are athletes at risk of nutrient deficiencies?

If you are an athlete with persistently poor nutritional habits, then yes. A poor diet is the primary cause of nutritional deficiency. Otherwise, the simple answer is, possibly.Exercise is indeed a powerful tool for maintaining health but athletes are not immune to the effects of a bad diet and/or increased nutrient loss. A deficiency in one or more nutrients over several days or weeks may impair your recovery and decrease your performance by reducing your ability to train (an effect of iron deficiency anaemia) or by increasing your risk of injury or illness (an effect of vitamin D and calcium deficiency). That said, adopting a healthy eating pattern reduces your risk of developing a nutrient deficiency.

A nice analogy to consider is the Formula 1 racing car. Team mechanics apply their graceful touches to the engine to keep it as fast and as economical as is required for the conditions of the track and the demands of the race. Feed the engine the wrong fuel, the engine fails, and all the hard work was futile... An athlete consuming a terrible diet will eventually find holes in their return to form. Fix the diet, optimise the recovery.

Compared to regular folk, an athlete’s engine is revving faster and for longer and needs to be well-tuned. Compared to regular folk, athletes’ nutritional requirements increase for some but not all nutrients. For example, when training load increases, total daily caloric intake must also increase because of the greater carbohydrate and fat utilisation during sessions and the greater need for protein to help repair, strengthen, and grow. Because more food must be eaten to meet the expense of the firing engine while leaving enough energy available for normal bodily function, it is often a natural extension that most nutrients are also consumed in greater amounts. For example, a study of 419 male and female international athletes found that daily intakes of vitamins and minerals were positively associated with daily caloric intake - the more food athletes ate, the greater their micronutrient intake, and the further above the specific RDA values they rose.

Studies show that a healthy eating patterns and sufficient energy availability are not widespread in elite athletes, that macronutrient recommendations are often not achieved, and that inadequate dietary habits are associated with nutritional deficiencies. Naturally, there are also some situations where specific nutritional demands might increase. Excessive sweating, particularly when living or training in hot or humid environments, can increase daily requirements of some micronutrients including minerals like sodium, iron, zinc, and magnesium, while menstruation, regular blood donation or training at high altitude can increase the need for iron. But these are not necessarily indications that a supplement is needed - the increased requirement can be achieved with whole foods. That said, situations do exist where dietary supplements are indicated. For example, iodine is advised in people not consuming iodised salt or living in areas with low levels of iodine in foods. Folate is advised in women planning a pregnancy. And, vitamin B12 is advised in those who exclude meat in their diet - vegetarians/vegans - since it is not generally found in plants (with the exception of some algae that are not commonly eaten).

Since healthy eating patterns are not widespread, nutrient deficiencies can be rather common. According to a 2018 IOC Consensus Statement and evidence from other surveys, there are three classic deficiencies that athletes often present with:

Over-the-counter dietary supplements are a supplement to, but not a replacement for, healthy eating patterns. Taking a self-prescribed daily nutritional supplement as an “insurance policy” might seem sensible but how do you know whether it is doing good, doing nothing, or causing harm? Clinical tests are highly-informative decision-making tools but they are not a replacement for being a master of your nutritional choices - implementing healthy eating habits can start today and will help prevent nutrient deficiencies arising before you head to your doctor. For example, iron needs can be met by eating meat, fish, and poultry, or plant sources like lentils, nuts, and dark green veg; vitamin C, which increases the absorption of iron, can be found in oranges, lemons/limes, raspberries, and grapefruit; vitamin D can either be synthesised by exposure to UV (but lying in the sun is not particularly healthy) or by eating oily fish (salmon/tuna), egg yolk, or foods fortified with vitamin D; and calcium can be consumed in dairy or fortified soymilk.

How can you sustain a healthy eating pattern?

Firstly, don’t lose your mind over food. Orthorexia, the unhealthy preoccupation with healthy eating, is a thing and studies estimate its prevalence at 55.3% in folks who exercise (95% confidence interval 43.2% to 66.8%). Keep calm. Your diet doesn’t have to be perfect. Yes, a consistently terrible diet will disrupt your recovery from and adaptations to your sessions and acutely impair your performance. But, just like a missed training session doesn’t delete your fitness, a single day of bad food choices among several days of a consistent healthy eating practice won’t jeopardise your health or fitness. Simply aim to get it right, most of the time.To help stay calm and on track, use this simple but effective logical strategy:

Plan it.

Get it.

Prep it.

Cook it.

This strategy has been used by world-renowned sports nutritionists and successfully-implemented in research and performance practice. It involves working out what food you need, how you can get it, how you can prep it, and how you can cook it. Perhaps you need to “shop smart” with a grocery list and use a grocery store strategy? Maybe you need to arrange and stock your kitchen with the nutritious foods you need? Perhaps you need to plan your meals each week or even batch prep so you have food ready to heat and eat? Make sure you always have what you need, either at home, in your bag, or with you at work - don’t allow your daily tasks to become the barrier to healthy eating - stock the fridge in anticipation of a large session or race. It is even possible that you need to learn how to cook. And, make mealtimes fun and introduce new ideas by sharing the cooking load with your friends and family. To help streamline these healthy eating strategies, check out the useful info on the Choose My Plate eat healthy budget page...

Get it.

Prep it.

Cook it.

Your healthy eating pattern should be sustainable every day. As an athlete, you are very likely to be travelling a lot, for races or even just for training. Being in new and unfamiliar environments can throw a spanner in the works. Planning your nutritional travel strategy ahead of time will keep you calm and well fed:

In the absence of being held in custody, to support your quest for a healthy eating pattern, a collaboration between the United States Olympic Committee Sport Dietitians and the University of Colorado (UCCS) Sport Nutrition Graduate Program developed “The Athlete’s Plates” (which were validated in 2019). The Athlete’s Plates provide a visual guide to help you learn what a variety of nutrient dense foods looks like. The birds-eye views of the easy-, moderate-, and hard-training plates show the relative areas that carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and fruit and veg should cover on your plate. Since your training load will vary from day-to-day and week-to-week depending on your training phase, eating to fuel your sessions (or races) and recover from them will depend on how hard your sessions are. So, the Athletes’ Plates provide useful visual clues as to how the relative amounts of the different food groups might vary in line with different daily training loads.

For example, “Moderate day meals” contain lean protein foods covering about a quarter of your plate, with the remaining three-quarters equally divided between whole-grain carbohydrate sources and vegetables. Moderate day meals are relevant on a moderate-effort training day that might include two sessions but with a focus on technical skill in one and endurance in the other. The moderate day is your baseline from where you adjust your plate down (for easy days) or up (for hard days or race days).

×

![]()

“Easy day meals” also contain lean protein foods covering about a quarter of your plate with slightly less whole-grain carbohydrate sources and more vegetables and fruits. These meals are appropriate on an easy training day that might include an easy-effort workout or during a taper that doesn’t require the need to “load” calories for an imminent race. (Easy day meals are also relevant to a weight management period in athletes trying to lose weight or athletes in sports requiring less energy due to lower daily training loads.

×

![]()

“Hard day meals” also contain lean protein foods covering about a quarter of your plate but now the carbohydrate sources are increased and cover about half of the plate, primarily from grains like white rice, pasta, bread, and potatoes with less whole grains - this reduces fiber to reduce the risk of GI issues during hard training or races. Hard day meals are for hard-effort training days that contain a race or at least 2 workouts that are relatively hard. If your race requires extra fuel from carbohydrates, “hard day meal” plates are useful for carbohydrate loading before race day and on race day.

×

![]()

You will notice that the Athlete’s Plates do not suggest any caloric loads or energy availability values required to maintain healthy performance. The important things to note are their:

The Athletes’ Plates are a guide, not a rule. To help put healthy eating into practice, work with a registered sports nutritionist/dietician for the best outcome and for a deeper dive into the topic, the IAAF (now called World Athletics) published a consensus statement in 2019 on Nutrition for Athletics, headed by Professor Louise Burke.

What can you add to your training tool box?

Occasionally we hear from athletes who "don't care about their nutrition" and "eat what they want". But eating what you want and eating what you need are two very different things. Going back a few moons, I recall the British Decathlete, Dean Macey, being adamant about nutrition not mattering. Macey was an affable “bloke down the pub” kind of guy and a world-class decathlete. But he was the “nearly man”, coming 4th at both Olympics he attended. Macey had an injury ravaged career that eventually forced him to retire and I always wondered whether his nutritional apathy came back to bite him in the ass. Could a healthy eating pattern have helped Macey sustain a healthier career? Could a healthy eating pattern have plonked him on an Olympic podium? We will never know. But, one thing for sure, it would not have hurt.A professional athlete not doing all they can to be the best they can be, is remarkably foolish. A builder never leaves out the foundations ahead of constructing their masterpiece. Ignoring nutrition and expecting to fulfil your genetic potential is a silly game that I suggest you avoid. So, to leave you with something to chew on, here are some nuggets to put in your recovery tool box:

Take meals seriously but don’t stress. Simply aim to have fun with nutrition and enjoy your food journey. All is not lost if things get eff dup from time to time. Just aim to eat well on as many days as possible by including a variety of nutrient-dense foods of all colours across and within all food groups. And, if you have no clue what you are doing, consult a registered sports nutritionist/dietician.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. I will be staying on the recovery track for a little while longer and will soon return with a look at exercise-nutrient timing. Until that time, keep eating smart and if you want to

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.