Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery for runners and endurance athletes.

→ Part 1 — Eat, sleep, rest, repeat.→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery 101: Eat, sleep, rest, repeat.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

23rd May 2020.

Your performance is a manifestation of appropriate training. Your training adaptations are dictated by the frequency, intensity, time and type of your sessions, the progression of your load, and your recovery from it. Being “ready to go again” is critical for making fitness gains in a healthy manner. In this series on recovery, I will unravel what recovery is and what you can do to optimise it.

Reading time ~20-mins (4000-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

As I frequently enjoy alluding to, Forrest Gump was a master of training load management and recovery. When he got tired, he slept. When he got hungry, he ate. And, when he had to go, you know, he went... Gump understood his basic bodily needs and fulfilled them by keeping things simple in order to adapt to the demands of his high training volume. As an endurance athlete, Gump nailed his recovery.

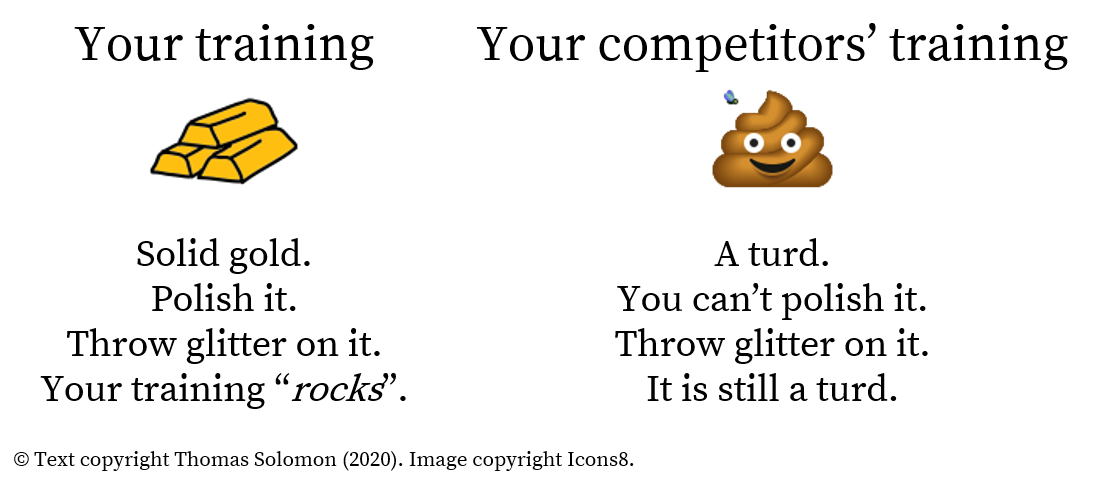

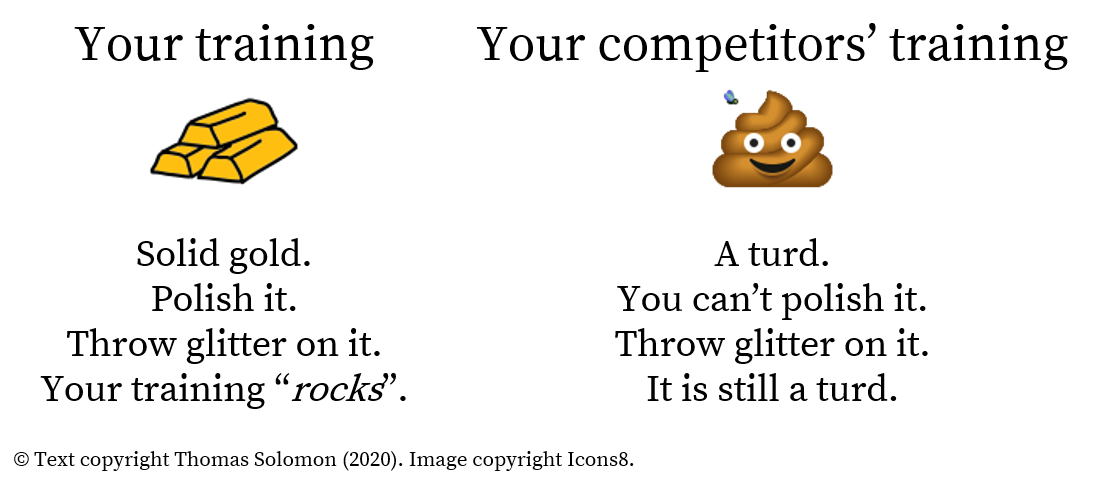

If you plan to build an amazing looking house but choose the wrong type of bricks and lay them incorrectly, the house will look rubbish. Yes, you can throw glitter on the house but, underneath, it will be flawed. Similarly, if you bugger up the mortar mix between the bricks, the structure will not be fit for purpose nor last through the seasons. The structure will collapse and neighbouring houses will stand tall for many moons beyond yours. Choose the right bricks, use the right mix. But that’s enough about bricks and glitter, which, incidentally, is a great name for a glam rock band. The point I am trying to make, albeit in an architecturally-bizarre manner, is that to build the performance level you desire, you need to use the right training load coupled with appropriate recovery.

Following a work-out, your inner-Jedi would say, “A disturbance in the force, there has been”. Darn right there has. The feeling of fatigue and muscle soreness is a consequence of the load imposed and the ongoing adaptive processes. But, they should not be confused with the quality of the stimulus - more pain does not equal more gain. Following your work-out, the time it will take you to be “ready to go again” is dependent on the intensity, duration, and type of work-out you completed, your energy and hydration status prior to, during, and following the work-out (i.e. your nutrition), the ambient level of psychological stress you are under (due to work, life, school, family, love, etc), illness/infection, injury, and environmental conditions like temperature, humidity, and altitude. As you are no doubt aware, the fitness improvement and eventual performance outcome of your training are influenced by EVERYTHING. The best athletes are well-versed in this sentiment. Remember that your work-out may be metabolically-demanding, muscle-damaging, or psychologically-fatiguing, or any combination of these factors. The recovery that follows must cover all bases.

Your recovery time between sessions is what will keep you adapting to your training load and the ingredients of that recovery time will determine the magnitude of the adaptation as well as the direction of adaptation. The time you need to be ready to go again is unique to you, so monitor it. Yes, the desired adaptation is one that gradually elevates your fitness and manifests an improvement in performance. Frustratingly, the world has become congested with a long list of things that fuel the usage of the verb form of recovery. Consequently, you can easily bugger up your mortar mix and cause undesired adaptations that do not improve your fitness and can harm your performance.

Keep things simple and only use approaches that are guaranteed to help you recover and optimally adapt.

Keep things simple and only use approaches that are guaranteed to help you recover and optimally adapt.

Don’t try to be a giraffe aiming for the high branches. Pick the low-hanging fruits; the easy-to-access habits of daily living that will support optimal recovery.

Don’t try to be a giraffe aiming for the high branches. Pick the low-hanging fruits; the easy-to-access habits of daily living that will support optimal recovery.

Photo by Slawek K on Unsplash.

What am I blabbing on about? Well, since your dawn of existence, there are three things that you have religiously-practiced every day, the quantity and quality of which have shaped your physical and psychological well-being to the fine form it is in today. You have not had to reach for the “high branches”. These three things are also the foundation of what you should be doing when you are doing recovery. Without further ado, get your house in order:

Eat well and at the right time, between sessions.

Eat well and at the right time, between sessions.

Educate yourself in healthy eating.

Learn the nutritional needs of an athlete.

Learn to cook.

Stock your kitchen with simple and nutritious food.

Perhaps consult a nutritionist/dietician.

Sleep lots and sleep soundly, between sessions.

Sleep lots and sleep soundly, between sessions.

Reduce your p.m. caffeine intake.

Reduce your alcohol intake.

Reduce your p.m. screen time.

Sleep in a dark, silent, cool, and distraction-free room.

Rest your body and your mind, between sessions.

Rest your body and your mind, between sessions.

Schedule and dedicate peaceful and uninterrupted “me time”.

During that time, do things that are restful for body and mind.

Notice that I refer to these things as what is happening in between sessions. This is important. A quick analysis of some of the world-class endurance runners who log their training on Strava shows that, on average, they accumulate upward of around 400 training hours a year. There are about 8760 hours in a year so such an athlete is exercising for only about 5% of their time and has the remaining 8360 hours a year to do with what they will. Placing all the emphasis on the measly amount of time spent exercising and investing nothing at all into the 95% of time spent doing other stuff would appear absurd. Yet, that is what many mortals do every single day and mere mortals have way more than 95% of their time spent not working out. So, think for a moment... When was the last time you planned to optimise your sleep quality or dedicated time to see whether you were “fueling for the work required”, as Prof James Morton would say? If all of this is a little bewildering and you do not know where to start, fear not, coming soon is a follow-up post on sleep and a series on nutrition in which I will dig into the science and provide more specific info on what you can do to recover like a pro.

Why is this important?

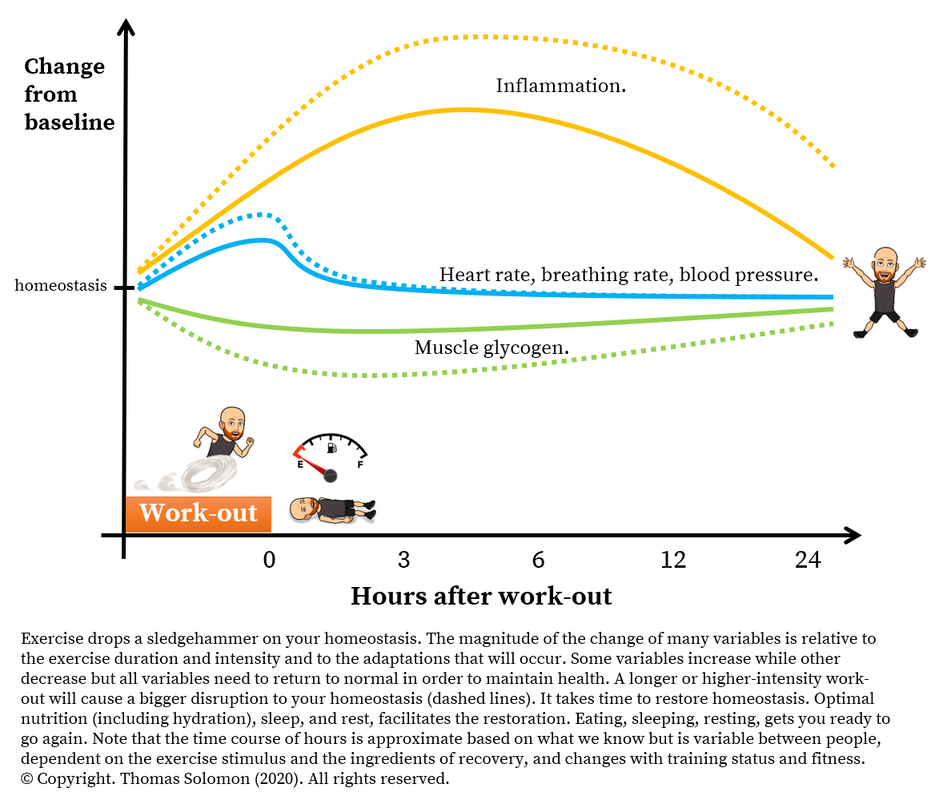

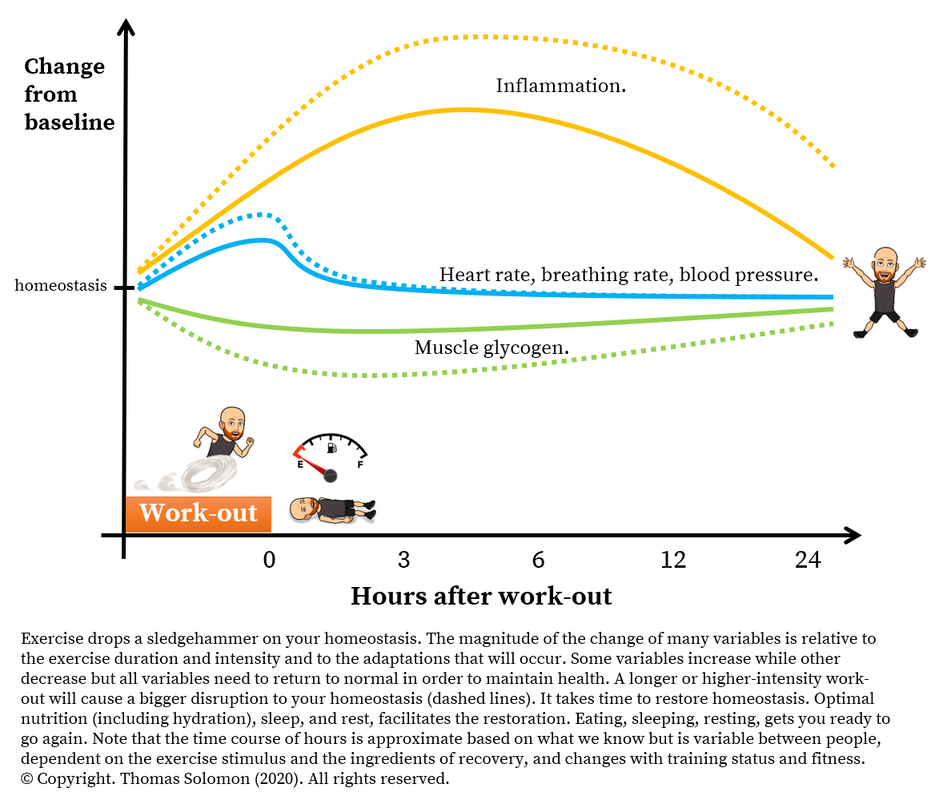

Well, smashing your exercise sledgehammer upon your homeostasis requires time to allow restoration. The magnitude of the homeostatic disruption is also correlated with both the intensity and duration of the session. So, increasing the time between hard sessions can be a simple fix for ensuring optimal adaptation and the maintenance of health. This is why mastering an effective programme design is key - plan, design, review. Remember that you do not have to do hard track sessions on Tuesdays and on Thursdays just because those are the traditional days your club meets.

Making a tweak to your exercise dose (i.e. your frequency ✕ intensity ✕ time) and progression is way to help remedy your lack of readiness to go again. But the wise Jedi master within you would also evaluate what is occurring during that time between your sessions. In essence, optimising your recovery from and adaptations to exercise comes down to three simple things: eating, sleeping, and resting. The online world appears to be full of “biohackers”, people who think they can “play God” and fool their biology. These “short-cut addicts” are folks who want to know what device, pill, potion, or session will make them leaner, faster, and stronger, today. During my days on this Earth, several athletes have asked me what they can take or use to “speed up their recovery”. In every case, the athlete has never considered what they mean by speeding up their recovery. Fortunately for me, only a couple of all the people I have advised, trained, and coached in performance and in health have been “short-cut addicts”. I build people’s fitness by choosing the right bricks and using the right mix. No short-cuts. No snake oil. My athletes focus their time on trying to train, eat, sleep, and rest as best they can.

In my experience, the “biohacking”, “get fit quick”, “short-cut addicts” always seem so willing to invest large resources in silly things that will have negligible gain while neglecting to optimise the obvious things first. My advice is always simple: eat well, sleep lots, and relax your body and mind. Your expendable resources should first be invested into those three important, non-negotiable, and returnable factors. As I will explain in forthcoming posts, low energy availability (inadequate nutrition in relation to the demands of exercise), dehydration, and inadequate sleep each massively decrease exercise performance while optimal nutritional choices (including hydration) and sleep hygiene will supercharge your ability to live well, recovery optimally, and perform highly. Furthermore, as I will also explain in a future post, there are only a few legitimate devices, pills and potions that improve physiological and/or psychological adaptations and, in some cases, even performance. Yes, the placebo effect is a very real thing, but so are people’s bank balances, time, and health. And, feeling recovered and/or believing that you are recovered is a very different thing to actually being recovered and adapting in a favourable direction. So, start simple, and after you have raised the bar of your nutrition, sleep, and restful habits to world-class levels, then you might consider the supplemental approaches. A good mantra to learn is Steve Magness’ first rule of training, “the boring stuff is your foundation”. So, choose the right bricks, use the right mix, then throw on the glitter.

Immediately after every session, ask yourself:

Immediately after every session, ask yourself:

"What was my perceived level of exertion today?" (session-RPE; aka intensity)

Rate your “RPE” during the session out of 10, where 2 = walking and 10 = maximal effort. To supplement the session-RPE intensity rating, you may also record (grade-adjusted) pace, heart rate, power, or weight lifting, in order to help track real performance outcomes.

And, ask yourself:

And, ask yourself:

"How did I feel?"

Rate your feeling during the session out of 5, where

5 = "I felt like the hulk",

4 = “I felt good”,

3 = “I felt average and/or a bit flat or off”,

2 = “I felt rubbish and could not maintain the quality throughout”,

1 = “I felt so terrible, tired, or ill, that I did not train or had to abort mission”.

Record:

Record:

Session duration (time in minutes; or, sets ✕ reps for weights sessions)

Session type (terrain, elevation gain, intervals/steady-state, interval number, interval duration, and interval-RPE)

And, calculate your session’s training load:

And, calculate your session’s training load:

= session-RPE ✕ session-duration (in minutes)

or

= session-RPE ✕ sets ✕ reps, for weights sessions

That takes care of monitoring your training load. It is very common to find that simply dialling back your current load will help improve your “readiness to return” to the next session. Also, remember that your performance is not defined by a single session. Your performance is honed by a journey of well-considered and timely exercise stimuli combined with adequate recovery in the form of good nutritional choices, sufficient and high-quality sleep, and rest.

So, to assess your recovery, consider doing the following:

When you get up in the morning, ask yourself:

When you get up in the morning, ask yourself:

“How do I feel right now?”

Rate your feeling out of 5, where

5 = "I feel amazing",

4 = “I feel good”,

3 = “I feel average”,

2 = “I feel rubbish and am not ready for the day”,

1 = “I feel terrible and want to stay in bed”.

Then, ask yourself:

Then, ask yourself:

“Am I currently feeling totally exhausted, run-down, or extremely tired?”

“Over the last one to two nights, have I slept poorly?”

“Over the last one to two days, have I eaten poorly?”

“Over the last one to two days, have I been under emotional stress?” (from work, or life events, or training/racing)

“Over the last one to two days, have I been under physical stress?” (from hard sessions and/or physical labour)

“Do I currently have any muscle or joint soreness that has lasted more than 24-hours?”

“Do I currently have an injury that is causing me pain and discomfort?”

Use your answers to help you make a decision about today’s session.

Use your answers to help you make a decision about today’s session.

Checking in with yourself on a regular basis and looking for true patterns is sensible and will help you make a decision whether or not to train today and/or how hard to train today. Finding the perfect balance between your training load and your recovery from it is all about you, getting to know yourself, and trusting yourself to make the best judgement call. Note: For more detailed info on using self-reported feelings to assess your recovery using approached like the POMS (profile of mood state) questionnaire and recovery-stress questionnaires like PRS and REST-Q, which have been used successfully in athletes of all ages and abilities, I can recommend the following reading: Morgan et al. (1988), Gutmann et al. (1984), Laurent et al. (2011), Piacentini et al. (2015), and Kallus et al. (2016).

Beyond your feelings of recovery, you may also consider some performance tests to objectively investigate your “readiness to perform”. This can also be useful for helping understand what type of taper is optimal for you prior to a key event. When selecting such tests, keep them simple and manageable while also considering the ecological validity in relation to your sport. In other words, select a test that is manageable for you, and that is relevant and specific to your goal. You must also consider that the outcome data is only useful if you have a reference point, i.e. having data points collected under “fatigued” and “recovered” conditions. Such approaches are discussed in more detail in a recent consensus statement on the topic, published in 2017 in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance.

Incorporating performance tests into your training every few weeks will help you understand your rates of recovery and will help optimise your taper periods ahead of your “A” races. Examples of tests can include recording steady-state heart rates and RPE at fixed sub-maximal speeds like your easy run pace and threshold pace or time trials over relevant and manageable distances that will not cause undue fatigue. For example, if you are training for a marathon it is not sensible to use a 26.2-mile time-trial to investigate your recovery but it could be useful to track your heart rate and RPE during a shorter, sub-maximal test, like a 30- to 60-minute run at marathon pace. Other examples of informative performance tests include 1-rep max lifting tests, critical power tests, or peak power tests. You will notice, for example, that your vertical jump height (an indication of your peak power) will be severely impaired in the minutes and hours after a hard session and will likely still be blunted in the days following a hard training block.

If you trained Hard today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after.

If you trained Hard today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after.

If you accumulated Hard-time today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after.

If you accumulated Hard-time today, you probably need to train Easy tomorrow and possibly also the day after.

If you felt like total shit today, you probably need some rest.

If you felt like total shit today, you probably need some rest.

Do not ignore your feelings - they are your “thermostat”.

Do not ignore your feelings - they are your “thermostat”.

Then, using these rules-of-thumb combined with your newly-learned recovery assessment toolbox, have a conversation with yourself:

How do I feel this morning?

How do I feel this morning?

… Hmm, about a 2 out of 5.

Why do I feel like that....?

Why do I feel like that....?

Did I sleep well or enough last night?

Did I sleep well or enough last night?

… No, not really.

Did I eat well yesterday?

Did I eat well yesterday?

… No, definitely not.

Am I ill or getting sick?

Am I ill or getting sick?

… Yes, I am developing some mild cold virus symptoms.

Did I do a long or hard session yesterday or the day before?

Did I do a long or hard session yesterday or the day before?

… Yes. I gave it large.

Hmmm… I probably need to rest today but that is fine because I know that missing training for a day (or even a few days) will not delete my fitness. Actually, it will most likely reinvigorate me. And, since I might be getting ill, it will allow me to stay healthy and return stronger.

Hmmm… I probably need to rest today but that is fine because I know that missing training for a day (or even a few days) will not delete my fitness. Actually, it will most likely reinvigorate me. And, since I might be getting ill, it will allow me to stay healthy and return stronger.

No automated metric other than a subjective self-assessment of your honesty is able to provide you with this detailed level of information. Learning to ask yourself some simple but informative questions and learning that ignoring how you feel will lead to the dark side, are the two simplest and most accurate ways you can monitor your recovery. Take on board what we know from prior meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the literature: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures. But always remember that data without knowledge is uninformative and useless. So if you don't know what the variable means, its accuracy and precision, the confounding factors, and what actionable change could or should be implemented, then re-consider why you are measuring anything at all.

I have done this ever since coming out of the surgery room in 2000 as a 20-year-old runner who had been poorly coached as a teenager with no learning of what training loads were or what recovery should entail. That surgical experience 20-years ago, left a scar on each knee from iliotibial band surgery but was the catalyst that made me peer into the world of exercise science and coaching practice, pushing recovery to the forefront of training approaches. Over the last 20-years, it has been a pretty smooth ride. A tibialis anterior issue put me out of action for two months in 2007 after a PB-producing (15:26) 5 km training period and a patella tendon issue, caused by slipping down Skiddaw, put me out of action for 3-weeks in the winter of 2017. Yes, there have been a couple of minor aches and pains but these have all been remedied by easing off the load for a couple of days and then easing back into it…

On a daily basis, my immediate post-workout routine is habitual. A cold glass of water (I find this refreshing), a small tasty snack of whatever I was craving at the end of the session (usually one of two things: some bread and cheese with some meat, olives and green salad; or a kanelsnegle, aka a cinnamon bun), and then some relaxing in my reading chair (which a Swedish person made) next to my drinking table (which a Ginger person made), while staring out the window listening to a podcast or reading a book. If it is the evening, the podcast/book gets exchanged for a glass of beer, especially something like a stout. Nutrition and rest. On top of daily recovery, I also plan recovery days into my schedule when I know that I will be free from work and chores and will be cushioned in peace and quiet. On such days, I always read a lot, listen to music, take a gentle hike with my wife, and go see a movie. These approaches are unique to me but I focus on the fundamentals.

You are not me. You are the only you. Find your way but keep it simple. I can never emphasise it enough: to train smart, do your utmost to eat well, sleep lots, and rest your body and your mind. Until next time, practice becoming a master of those three simple things.

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

But, what is recovery?

Each of your work-outs provide a stimulus in the form of a multifaceted stress, personified as mechanical load, neuron activation, metabolic disturbance, and hormone responses. Before the “storm” of exercise, your body is in a state of homeostasis. Your heart rate, breathing rate, and blood metabolite/hormone/cytokine levels are all within the normal resting reference ranges. Exercise drops a sledge-hammer on your homeostasis. Recovery is the process of acute restorative adaptations, both physiological and psychological, that happens to your body in between exercise sessions to restore homeostasis, allowing you to be ready to train or compete again. To put it simply, recovery is your readiness to go again. Recovery is not simply the time of your day when you are not exercising. Recovery should be considered an essential component of your training. Plan it. Do it. Review it. Just as you do for your sessions. As Christie Aschwanden so eloquently describes, “Recovery has become a verb”.If you plan to build an amazing looking house but choose the wrong type of bricks and lay them incorrectly, the house will look rubbish. Yes, you can throw glitter on the house but, underneath, it will be flawed. Similarly, if you bugger up the mortar mix between the bricks, the structure will not be fit for purpose nor last through the seasons. The structure will collapse and neighbouring houses will stand tall for many moons beyond yours. Choose the right bricks, use the right mix. But that’s enough about bricks and glitter, which, incidentally, is a great name for a glam rock band. The point I am trying to make, albeit in an architecturally-bizarre manner, is that to build the performance level you desire, you need to use the right training load coupled with appropriate recovery.

What are you recovering from?

When you complete a session, you place yourself under both physical and psychological stress. To you, the stress response is noticeable as a feeling of fatigue and muscle soreness. Within your body, the stress response is measurable as an increase in reactive oxygen species (in muscle and blood), which can cause oxidative stress; an increase in inflammatory cytokines (in muscle and blood) and immune cell infiltration into muscle; a decrease in muscle and liver levels of glycogen, your bodily store of glucose; a decrease in intramuscular triglyceride levels, your muscles’ fatty acid store; and an increase in muscle protein synthesis that requires amino acid availability to help outweigh the increase in muscle protein breakdown. If muscles have been damaged, due to eccentric contractions that occur during strength training, downhill running, or prolonged, hard sessions, there will also be detectable increases in creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase in blood. In short, there is a massive disruption in homeostasis that needs to be remedied. Note: you can read more about what happens inside your muscle in a previous post.Following a work-out, your inner-Jedi would say, “A disturbance in the force, there has been”. Darn right there has. The feeling of fatigue and muscle soreness is a consequence of the load imposed and the ongoing adaptive processes. But, they should not be confused with the quality of the stimulus - more pain does not equal more gain. Following your work-out, the time it will take you to be “ready to go again” is dependent on the intensity, duration, and type of work-out you completed, your energy and hydration status prior to, during, and following the work-out (i.e. your nutrition), the ambient level of psychological stress you are under (due to work, life, school, family, love, etc), illness/infection, injury, and environmental conditions like temperature, humidity, and altitude. As you are no doubt aware, the fitness improvement and eventual performance outcome of your training are influenced by EVERYTHING. The best athletes are well-versed in this sentiment. Remember that your work-out may be metabolically-demanding, muscle-damaging, or psychologically-fatiguing, or any combination of these factors. The recovery that follows must cover all bases.

Your recovery time between sessions is what will keep you adapting to your training load and the ingredients of that recovery time will determine the magnitude of the adaptation as well as the direction of adaptation. The time you need to be ready to go again is unique to you, so monitor it. Yes, the desired adaptation is one that gradually elevates your fitness and manifests an improvement in performance. Frustratingly, the world has become congested with a long list of things that fuel the usage of the verb form of recovery. Consequently, you can easily bugger up your mortar mix and cause undesired adaptations that do not improve your fitness and can harm your performance.

×

![]()

Keep recovery simple — eat, sleep, and rest.

Recovery, the verb, should involve aiding the restoration of homeostasis, bringing your physiology and your psychology back to a state of calm. Recovery should not involve “shooting the messenger". In other words, during the precious time you have between your sessions, you should never do things that will impair your adaptations to the exercise stimuli. Suppressing the feeling of muscle soreness has a time and a place but soreness is an indication of the inflammatory repair processes that are occurring to help prompt an adaptation. Antioxidant supplementation, ice baths, compression, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are all examples of approaches used to reduce the feeling of soreness and promote the feeling of recovery. They have their time and place but, as will be discussed in a future post, each of these approaches blunts the intracellular signalling processes that eventually lead to long-term adaptations. So, my advice is:

×

![]()

There are tonnes of “recovery methods” thrown around that you can spend your time and money on, including devices, supplements, potions, and contraptions. Lots of choices. Lots of marketing. Lots of unknowns. After many years in this game as a scientist, an athlete, and as a coach, I have encountered many people trying to eke out the final few strides of genetic potential in their legs. Regrettably, many folks do this by throwing glitter onto their training rather than making sure their training is not a turd. And, remember, by “training” I mean both the exercise stimulus and the recovery between sessions. Such folks are very likely far from their genetic potential because they have not chosen the right bricks or used the right mix.

What am I blabbing on about? Well, since your dawn of existence, there are three things that you have religiously-practiced every day, the quantity and quality of which have shaped your physical and psychological well-being to the fine form it is in today. You have not had to reach for the “high branches”. These three things are also the foundation of what you should be doing when you are doing recovery. Without further ado, get your house in order:

Educate yourself in healthy eating.

Learn the nutritional needs of an athlete.

Learn to cook.

Stock your kitchen with simple and nutritious food.

Perhaps consult a nutritionist/dietician.

Reduce your p.m. caffeine intake.

Reduce your alcohol intake.

Reduce your p.m. screen time.

Sleep in a dark, silent, cool, and distraction-free room.

Schedule and dedicate peaceful and uninterrupted “me time”.

During that time, do things that are restful for body and mind.

Notice that I refer to these things as what is happening in between sessions. This is important. A quick analysis of some of the world-class endurance runners who log their training on Strava shows that, on average, they accumulate upward of around 400 training hours a year. There are about 8760 hours in a year so such an athlete is exercising for only about 5% of their time and has the remaining 8360 hours a year to do with what they will. Placing all the emphasis on the measly amount of time spent exercising and investing nothing at all into the 95% of time spent doing other stuff would appear absurd. Yet, that is what many mortals do every single day and mere mortals have way more than 95% of their time spent not working out. So, think for a moment... When was the last time you planned to optimise your sleep quality or dedicated time to see whether you were “fueling for the work required”, as Prof James Morton would say? If all of this is a little bewildering and you do not know where to start, fear not, coming soon is a follow-up post on sleep and a series on nutrition in which I will dig into the science and provide more specific info on what you can do to recover like a pro.

Training outcome = Training load + Recovery.

Doing too much, too often, too soon, is a fast track route to feeling like poop every time you lace up. These are traits I see far-too-often in athletes who are eager to “get fit quick” and in those returning from an injury. My spidey senses are also tingling when I think about athletes who will return to normal training after our current COVID-enforced era of lock-down. Please start low, go slow, and ramp up gradually. But, whatever is the cause of a too much, too often, too soon period of training, the simple fix is to first ask yourself whether you are doing too many hard sessions too frequently?Why is this important?

Well, smashing your exercise sledgehammer upon your homeostasis requires time to allow restoration. The magnitude of the homeostatic disruption is also correlated with both the intensity and duration of the session. So, increasing the time between hard sessions can be a simple fix for ensuring optimal adaptation and the maintenance of health. This is why mastering an effective programme design is key - plan, design, review. Remember that you do not have to do hard track sessions on Tuesdays and on Thursdays just because those are the traditional days your club meets.

Making a tweak to your exercise dose (i.e. your frequency ✕ intensity ✕ time) and progression is way to help remedy your lack of readiness to go again. But the wise Jedi master within you would also evaluate what is occurring during that time between your sessions. In essence, optimising your recovery from and adaptations to exercise comes down to three simple things: eating, sleeping, and resting. The online world appears to be full of “biohackers”, people who think they can “play God” and fool their biology. These “short-cut addicts” are folks who want to know what device, pill, potion, or session will make them leaner, faster, and stronger, today. During my days on this Earth, several athletes have asked me what they can take or use to “speed up their recovery”. In every case, the athlete has never considered what they mean by speeding up their recovery. Fortunately for me, only a couple of all the people I have advised, trained, and coached in performance and in health have been “short-cut addicts”. I build people’s fitness by choosing the right bricks and using the right mix. No short-cuts. No snake oil. My athletes focus their time on trying to train, eat, sleep, and rest as best they can.

In my experience, the “biohacking”, “get fit quick”, “short-cut addicts” always seem so willing to invest large resources in silly things that will have negligible gain while neglecting to optimise the obvious things first. My advice is always simple: eat well, sleep lots, and relax your body and mind. Your expendable resources should first be invested into those three important, non-negotiable, and returnable factors. As I will explain in forthcoming posts, low energy availability (inadequate nutrition in relation to the demands of exercise), dehydration, and inadequate sleep each massively decrease exercise performance while optimal nutritional choices (including hydration) and sleep hygiene will supercharge your ability to live well, recovery optimally, and perform highly. Furthermore, as I will also explain in a future post, there are only a few legitimate devices, pills and potions that improve physiological and/or psychological adaptations and, in some cases, even performance. Yes, the placebo effect is a very real thing, but so are people’s bank balances, time, and health. And, feeling recovered and/or believing that you are recovered is a very different thing to actually being recovered and adapting in a favourable direction. So, start simple, and after you have raised the bar of your nutrition, sleep, and restful habits to world-class levels, then you might consider the supplemental approaches. A good mantra to learn is Steve Magness’ first rule of training, “the boring stuff is your foundation”. So, choose the right bricks, use the right mix, then throw on the glitter.

×

![]()

How can you assess your recovery?

Knowing what not to do is great but empowering yourself to lead your own training journey with success is golden. Training hard is about training smart and knowing when to step off the gas or even rest. Training hard is not about pushing through chronic pain, excess fatigue, or emotional stress. If you feel like you are not recovering between sessions, the first thing to examine is your training load. As I have discussed previously, to monitor the load imposed by your sessions, you can do the following:"What was my perceived level of exertion today?" (session-RPE; aka intensity)

Rate your “RPE” during the session out of 10, where 2 = walking and 10 = maximal effort. To supplement the session-RPE intensity rating, you may also record (grade-adjusted) pace, heart rate, power, or weight lifting, in order to help track real performance outcomes.

"How did I feel?"

Rate your feeling during the session out of 5, where

5 = "I felt like the hulk",

4 = “I felt good”,

3 = “I felt average and/or a bit flat or off”,

2 = “I felt rubbish and could not maintain the quality throughout”,

1 = “I felt so terrible, tired, or ill, that I did not train or had to abort mission”.

Session duration (time in minutes; or, sets ✕ reps for weights sessions)

Session type (terrain, elevation gain, intervals/steady-state, interval number, interval duration, and interval-RPE)

= session-RPE ✕ session-duration (in minutes)

or

= session-RPE ✕ sets ✕ reps, for weights sessions

That takes care of monitoring your training load. It is very common to find that simply dialling back your current load will help improve your “readiness to return” to the next session. Also, remember that your performance is not defined by a single session. Your performance is honed by a journey of well-considered and timely exercise stimuli combined with adequate recovery in the form of good nutritional choices, sufficient and high-quality sleep, and rest.

So, to assess your recovery, consider doing the following:

“How do I feel right now?”

Rate your feeling out of 5, where

5 = "I feel amazing",

4 = “I feel good”,

3 = “I feel average”,

2 = “I feel rubbish and am not ready for the day”,

1 = “I feel terrible and want to stay in bed”.

“Am I currently feeling totally exhausted, run-down, or extremely tired?”

“Over the last one to two nights, have I slept poorly?”

“Over the last one to two days, have I eaten poorly?”

“Over the last one to two days, have I been under emotional stress?” (from work, or life events, or training/racing)

“Over the last one to two days, have I been under physical stress?” (from hard sessions and/or physical labour)

“Do I currently have any muscle or joint soreness that has lasted more than 24-hours?”

“Do I currently have an injury that is causing me pain and discomfort?”

Checking in with yourself on a regular basis and looking for true patterns is sensible and will help you make a decision whether or not to train today and/or how hard to train today. Finding the perfect balance between your training load and your recovery from it is all about you, getting to know yourself, and trusting yourself to make the best judgement call. Note: For more detailed info on using self-reported feelings to assess your recovery using approached like the POMS (profile of mood state) questionnaire and recovery-stress questionnaires like PRS and REST-Q, which have been used successfully in athletes of all ages and abilities, I can recommend the following reading: Morgan et al. (1988), Gutmann et al. (1984), Laurent et al. (2011), Piacentini et al. (2015), and Kallus et al. (2016).

Beyond your feelings of recovery, you may also consider some performance tests to objectively investigate your “readiness to perform”. This can also be useful for helping understand what type of taper is optimal for you prior to a key event. When selecting such tests, keep them simple and manageable while also considering the ecological validity in relation to your sport. In other words, select a test that is manageable for you, and that is relevant and specific to your goal. You must also consider that the outcome data is only useful if you have a reference point, i.e. having data points collected under “fatigued” and “recovered” conditions. Such approaches are discussed in more detail in a recent consensus statement on the topic, published in 2017 in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance.

Incorporating performance tests into your training every few weeks will help you understand your rates of recovery and will help optimise your taper periods ahead of your “A” races. Examples of tests can include recording steady-state heart rates and RPE at fixed sub-maximal speeds like your easy run pace and threshold pace or time trials over relevant and manageable distances that will not cause undue fatigue. For example, if you are training for a marathon it is not sensible to use a 26.2-mile time-trial to investigate your recovery but it could be useful to track your heart rate and RPE during a shorter, sub-maximal test, like a 30- to 60-minute run at marathon pace. Other examples of informative performance tests include 1-rep max lifting tests, critical power tests, or peak power tests. You will notice, for example, that your vertical jump height (an indication of your peak power) will be severely impaired in the minutes and hours after a hard session and will likely still be blunted in the days following a hard training block.

Putting recovery into practice.

Instead of trying to fit a metric to a problem, which might include fitting your latest heart rate variability measurement to the way you feel, why not go directly to the problem and work backwards. For example, start with the suggested rules of thumb for informing your training decisions, which I described in my training load post:Then, using these rules-of-thumb combined with your newly-learned recovery assessment toolbox, have a conversation with yourself:

… Hmm, about a 2 out of 5.

… No, not really.

… No, definitely not.

… Yes, I am developing some mild cold virus symptoms.

… Yes. I gave it large.

No automated metric other than a subjective self-assessment of your honesty is able to provide you with this detailed level of information. Learning to ask yourself some simple but informative questions and learning that ignoring how you feel will lead to the dark side, are the two simplest and most accurate ways you can monitor your recovery. Take on board what we know from prior meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the literature: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures. But always remember that data without knowledge is uninformative and useless. So if you don't know what the variable means, its accuracy and precision, the confounding factors, and what actionable change could or should be implemented, then re-consider why you are measuring anything at all.

Your recovery is unique to you.

I use the above-described evidence-based approaches for all of my coached athletes. Those who religiously engage in my recovery tool are typically the most successful. I also used this approach with great success during my own athletic career. Nowadays, I continue to use it to ensure that my “having fun with exercise” approach to training keeps me healthy and far from a nonfunctional state of overreaching.I have done this ever since coming out of the surgery room in 2000 as a 20-year-old runner who had been poorly coached as a teenager with no learning of what training loads were or what recovery should entail. That surgical experience 20-years ago, left a scar on each knee from iliotibial band surgery but was the catalyst that made me peer into the world of exercise science and coaching practice, pushing recovery to the forefront of training approaches. Over the last 20-years, it has been a pretty smooth ride. A tibialis anterior issue put me out of action for two months in 2007 after a PB-producing (15:26) 5 km training period and a patella tendon issue, caused by slipping down Skiddaw, put me out of action for 3-weeks in the winter of 2017. Yes, there have been a couple of minor aches and pains but these have all been remedied by easing off the load for a couple of days and then easing back into it…

On a daily basis, my immediate post-workout routine is habitual. A cold glass of water (I find this refreshing), a small tasty snack of whatever I was craving at the end of the session (usually one of two things: some bread and cheese with some meat, olives and green salad; or a kanelsnegle, aka a cinnamon bun), and then some relaxing in my reading chair (which a Swedish person made) next to my drinking table (which a Ginger person made), while staring out the window listening to a podcast or reading a book. If it is the evening, the podcast/book gets exchanged for a glass of beer, especially something like a stout. Nutrition and rest. On top of daily recovery, I also plan recovery days into my schedule when I know that I will be free from work and chores and will be cushioned in peace and quiet. On such days, I always read a lot, listen to music, take a gentle hike with my wife, and go see a movie. These approaches are unique to me but I focus on the fundamentals.

You are not me. You are the only you. Find your way but keep it simple. I can never emphasise it enough: to train smart, do your utmost to eat well, sleep lots, and rest your body and your mind. Until next time, practice becoming a master of those three simple things.

×

![]()

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.