Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery for runners and endurance athletes.

→ Part 1 — Eat, sleep, rest, repeat.→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Sleep: a five-letter word to supercharge your recovery.

Thomas Solomon PhD.

11th Jun 2020.Updated on: 15th Dec 2023.

As I discussed in the first part of this recovery series, keeping your recovery simple is key: Eat, sleep, and rest. In this second part, to get you ready to go again, I will deeply dive into the science of sleep, the effects of sleep restriction and extension on your performance, and how you can optimise your sleep to harness its superpowers.

Reading time ~25-mins.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Recovery is the process of acute restorative physiological and psychological adaptations that occur in between exercise sessions to restore homeostasis. Recovery is your readiness to go again. Resting and sleeping not only help your physiological restoration but also your psychological recovery. Having your “head in the game” is a real thing and not feeling “on it” is something every person can relate to. Behavioural and cognitive aspects of being are critical for optimal performance. Racing may seem like a physiological pursuit but pacing strategy, tactical decisions, grit, and desire to win, are all psychological attributes. Training and racing are both physiologically and psychologically tiring and you can bring your “A” game back to the table by optimizing your sleep.

When you are getting your zzz’s, your brain “runs” through a cycle of stages. Stage 1 is very short and is a light sleep, a cat nap, during which you are still alert and can easily be woken. Stage 2 is also pretty light but is characterised by a sudden increase in the frequency of brainwave activity followed by a “slowing down”. Stages 3 and 4 are your deep sleep where muscles and tissues grow, develop, and repair, and immune function is improved. There is no eye movement or muscle activity during these phases and it is very difficult to be woken. Then there is a rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep, during which your brain activity spikes, you dream, your eyes “dance”, and your heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate increase. REM sleep first occurs about 90 minutes after initially falling asleep but you may have 5 or 6 REM cycles per night, each lasting up to an hour. During REM, you will be learning and developing memories, and consolidating new information so it can be stored in the long-term filing cabinet. These stages are measurable using electroencephalography (EEG), which detects waves of electrical activity in your brain. As Michael Stipe would say, “what’s the frequency, Kenneth?”

“It's The End Of The World As We Know It”. Calm down, go to sleep, and in the morning, “I will feel fine”. Paraphrasing, but Michael Stipe from REM was clearly a sleep biologist.

Without regurgitating 50-years of research, I will keep this simple. During sleep, the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through your brain increases, helping to provide more oxygen, nutrients, and hormones to neurons, removing metabolic products, and sending signalling molecules to other parts of your body. All stages of sleep are important, which is why prolonged and uninterrupted sleep is essential. As well as helping to regulate appetite and energy balance, with specific relevance to exercise recovery, accumulating sufficient amounts of uninterrupted sleep each night allows you to:

Consolidate new information, preserve memories, and organise the chronology of experiences to maintain and improve your intelligence, helping you to enhance your existing skills or develop new ones;

Consolidate new information, preserve memories, and organise the chronology of experiences to maintain and improve your intelligence, helping you to enhance your existing skills or develop new ones;

and,

Synthesise new proteins to build hormones, growth factors, and immunological and reproductive molecules to repair and maintain tissues to keep you physically strong, healthy, and “fit”.

Synthesise new proteins to build hormones, growth factors, and immunological and reproductive molecules to repair and maintain tissues to keep you physically strong, healthy, and “fit”.

Despite the immense dedication to understanding the neurobiology of sleep and its consequences, we still do not really know “why we sleep”; after all, many animals do not sleep in the way that we do. But sleep does appear to be an evolutionary tool that enables animals to hunt, gather, reproduce, resist infection, and fight. I.e., sleep will keep your physiological, psychological, reproductive and immunological health as sharp as the tools we once carved out of rock. Although life is slightly different for modern-day humans, you may have noticed that after one or two nights of poor or interrupted sleep, once seemingly easy tasks simply become awkward and frustrating. Yep, sleep is needed to prevent you from becoming a mental and physical shipwreck. No one enjoys a shipwreck.

Don’t be a shipwreck no matter how beautiful you look. Sleep.

For those of us aged 18 and older, the days of epic sleep are behind us, but the recommendations from the National Sleep Foundation are that we require

If you are highly active, the amount of sleep you need is likely higher, but the truth in that is not completely certain. Recent work found that elite athletes need about 8-hours sleep a night to “feel” rested and that 71% of athletes fail to meet this need on most nights. Due to a lack of research, there are no specific sleep guidelines for athletes and it is not known whether athletes actually need more sleep. Nonetheless, as I will get to if you stay with me on this journey, sleep restriction is not an athlete’s friend and sleep extension is so special it should be embraced at any opportunity. Any athlete, even a wise old master’s athlete in whom natural sleep duration and depth may be shortening, should be doing their best to sleep as much and as well as they can.

To summarise that rant, although “sleepiness”, the “propensity to fall asleep” and the “need for sleep” are not identical concepts, one thing is clear: we humans need sleep. Consequently, for you athletes, there is one burning question... is sleep the power tool you need in your athletic performance toolbox?

Several studies convincingly show that acute (1-night) and chronic (several days) reduction in nightly sleep decreases cognitive performance in athletes, including poorer reaction times, psychomotor vigilance, and sequence recognition. The recovery of impaired cognitive performance following sleep restriction in athletes also takes much longer when sleep has been impaired chronically. Sleep restriction also has a profound effect on reducing mood and motivation. We might speculate that this will also impair physical performance but, rather than making assumptions, let’s dig into the actual data…

A single night of complete sleep deprivation has been found to reduce muscle protein fractional synthetic rate in healthy men and women. This observation was found coupled with increased cortisol (a stress hormone) and reduced testosterone (an anabolic steroid hormone) levels in the blood. Sleep restriction (4 hours/night for 5 nights) in healthy and active young men also reduced myofibrillar protein synthesis (which may explain sleep-deprivation induced loss of muscle mass) but only in the absence of daily exercise. Sleep restriction can also modify the utilisation of metabolic fuel switching during periods of weight management. For example, it has been shown in overweight men and women that 2 weeks of moderate calorie restriction combined with normal or restricted nightly sleep led to the same weight loss (~3 kg) but having just 5.5-hours of sleep/night caused less fat loss and more fat-free mass loss compared to 8-hours/night. Further work has found that a single night's loss of sleep in young, healthy men and women caused genome-wide changes in DNA methylation that were coupled with metabolic biomarkers indicative of potential for muscle tissue breakdown and adipose tissue expansion, plus a decrease in glycolytic enzyme expression in muscle, changes in muscle clock genes, and increments in muscle inflammation. Lots of mayhem. Lots of potential for muscle dysfunction.

These above-described studies examined physiological measurements that might affect recovery and performance. But, what about actual performance?

Let’s do this!

Immediately following a single night of sleep deprivation, it has been shown in young college athletes that reaction times are delayed but peak cycling power is unaffected. However, in young male runners, 1-night of sleep deprivation has been shown to decrease treadmill endurance performance during a “run as far as you can in 30-minutes” test, with no change in RPE. Similarly, in male team-sports athletes, 1-night of sleep deprivation impaired mood, decreased muscle glycogen levels, and reduced shuttle running speed, when compared to data collected after normal habitual sleep. In relation to muscle strength, 1-night of sleep deprivation had an immediate negative effect on mood state followed by a loss of muscle strength the following day, in young males. In accordance with this “delayed” impairment in strength, peak torque during knee extension and flexion was reduced in US Marines, 2-days following a single night of sleep deprivation.

More extreme but less relevant periods of sleep deprivation have also been examined. Vertical jump height decreased following 64 hours of sleep deprivation in young male subjects but only when they were inactive and not engaging in intermittent exercise, which prevented the loss of jump height induced by this extreme sleep deprivation. In a separate study, 48 hours of sleep deprivation in young male athletes who underwent eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage did not affect the restoration of muscle strength when compared to 2-days of their normal habitual sleep. But, blood levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-6, and IGF-1, cortisol, and cortisol/total testosterone ratio were higher following 48-hours of sleep deprivation.

The effects of consecutive night sleep reduction have also been examined. In recreational weightlifters, sleep deprivation to 3 hours/night for 3 nights decreased mood and increased sleepiness and confusion after just 1 night and, after the second night, maximal and submaximal lifting ability was reduced and RPE increased. While in elite cyclists, 3 nights of 4 hours/night of sleep reduced maximal jump height and response time while impairing coordination during multiplanar tests when compared to test scores following their habitual 7.5 hours of sleep/night.

To summarise, it seems that maximum power is not affected immediately following 1-night of sleep restriction but is smashed the next day, while the effects on sub-maximal work are more immediate. Sports that require speed, tactical strategy, and technical skill are most sensitive to acute sleep deprivation while the effects on endurance manifest with repeated sleep deprivation. Of course, different study designs and between-subject variability in the outcomes are evident but because strength, endurance, strategy, and skill are the key to endurance success, the overall message is, to maintain your athletic abilities, don’t squash your sleep. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses now confirm that sentiment (see here, here, here, and here).

A 6-night period of sleep extension (~2-additional hours per night) prior to 1-night of total sleep deprivation lowered RPE during knee extensor exercise (submaximal voluntary contraction to fatigue) and prevented the sleep deprivation-induced reduction in time to fatigue, in young healthy men. These findings show that sleep extension before sleep restriction can help maintain neuromuscular function and are relevant to ultra races, many of which start in the middle of the night and continue until the next night, deleting one night of sleep. A planned period of sleep extension before an ultra race or a race that starts in the middle of the night may be a useful tool to help keep your motor control in check and your neurons firing just enough to keep you sharp. I have never raced an ultra but I have raced many marathons, completed a few training runs in and around the 30-mile mark, and regularly do 3 to 5 hour runs in the mountains. I have also played around with doing hard sessions off different amounts of sleep and at different times of the day and night. The clear pattern is that at the end of super loooong effort, not everything upstairs is working with 100% clarity, even if I have been well-fed; a hard session following a night of sleep deprivation does not proceed with grace; and, a hard session in the middle of the night just feels weird and wrong. It is wrong; one should be in bed.

A similar duration of sleep extension, 2-additional hours per night for 1-week, lowered sleepiness and increased the accuracy of serves in a small group of college-level tennis players. A longer-term period of sleep extension has also been examined in male college basketball players, where 6 weeks of sleep extension, aiming for 10 hours in bed (approx 2-additional hours sleep per night ), reduced sleepiness, increased mood, and improved sprint times and shooting accuracy. However, this study had no control group (sigh...) so improved performance due to 5-7-weeks of training adaptations cannot be ruled out.

Now, submaximal knee extensor contraction-to-failure, serving accuracy, and shooting accuracy may not seem relevant to endurance performance. You are correct; the external ecological validity is indeed poor. But, resisting neuromuscular fatigue is critical for endurance success and improved skill is one of the things that helps improve running economy. And, any obstacle racer will get shivers down their spine when they visualise the consequence of an inaccurate and missed spear throw. Extrapolation is nice but what about some hard evidence?

In 2019, investigators at Deakin University used a cross-over design to examine the effects of 3-nights of habitual (7 hours/night) vs. restricted (5 hours/night) vs. extended (9 hours/night) sleep on endurance performance, in trained male cyclists and triathletes. Sleep restriction impaired mood, psychomotor vigilance (cognitive reaction time), and time-to-completion in a cycling time-trial while sleep extension improved cognitive performance and endurance performance, when compared to habitual sleep. Interestingly, no changes in RPE were found suggesting that sleep extension enabled athletes to think quicker and ride faster at the same level of effort. Perhaps this sounds like a tool you’d like to be armed with during your next race.

As I said above, the recommended amount of daily sleep for adults is 7 to 9 hours and if you are highly active, the amount of sleep you need is likely higher. Whether or not highly-active people need more sleep than regular folks is uncertain. BUT, the emerging data clearly indicate that increasing your daily amount of sleep will enhance your recovery to go again. And, as Adharanand Finn noted in his book, Running with the Kenyans, the finest African athletes that we all admire, sleep a lot — just lounging around when not training and napping when they get bored of lounging. Perhaps sleep is one of the mightiest “power tools” in a world-class recovery toolbox. But, what can you be doing to help yourself recover like a pro?

Sleep is your recovery power tool.

Use it!

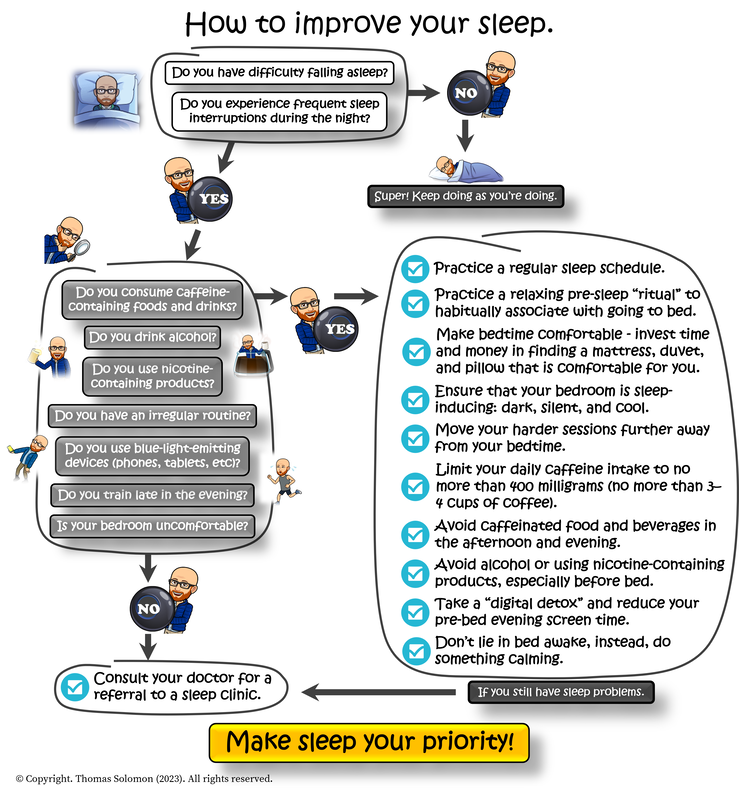

Sleep is awesome; sleep hygiene is essential. If you are not achieving your 7- to 9-hours of sleep per night, or if you are having difficulties falling asleep, or if you experience frequent interruptions to your sleep, do you ever wonder why? Besides excess light, noise, and high temperatures, some of your favourite things are also fuel for the night devil who keeps you awake...

Irregular routines, like those induced by night-time shift work, bash sleep and continue to negatively impact alertness during the days in between shifts, as shown in an Occupational Medicine review published in 2003.

Irregular routines, like those induced by night-time shift work, bash sleep and continue to negatively impact alertness during the days in between shifts, as shown in an Occupational Medicine review published in 2003.

Caffeine bashes sleep. Although there is a considerable degree of interindividual variability in the effects of caffeine, the speed of its metabolism, and your sensitivity to it, the consensus evidence suggests that caffeine detrimentally affects sleep hygiene (see here and here) by prolonging sleep latency (the time taken to fall asleep), decreasing sleep duration, and increasing the frequency of interruptions to sleep, even when ingested up to 13-hours before bedtime! Furthermore, caffeine does not reverse the detrimental effects of sleep deprivation. While some correlational evidence has shown that caffeine consumption might only be related to poorer sleep quality in people who do not typically drink caffeine in the evening, the correlation has not been proven experimentally and, why take the risk? Quality sleep will keep you functioning optimally while caffeine, even a tasty megafrappasexyccino, will only mask the feelings of sleepiness — it is not an antidote for chronic sleep loss.

Caffeine bashes sleep. Although there is a considerable degree of interindividual variability in the effects of caffeine, the speed of its metabolism, and your sensitivity to it, the consensus evidence suggests that caffeine detrimentally affects sleep hygiene (see here and here) by prolonging sleep latency (the time taken to fall asleep), decreasing sleep duration, and increasing the frequency of interruptions to sleep, even when ingested up to 13-hours before bedtime! Furthermore, caffeine does not reverse the detrimental effects of sleep deprivation. While some correlational evidence has shown that caffeine consumption might only be related to poorer sleep quality in people who do not typically drink caffeine in the evening, the correlation has not been proven experimentally and, why take the risk? Quality sleep will keep you functioning optimally while caffeine, even a tasty megafrappasexyccino, will only mask the feelings of sleepiness — it is not an antidote for chronic sleep loss.

Alcohol and nicotine bash sleep.

Alcohol and nicotine bash sleep.

Among the studies that have found negative effects of drinking and smoking on sleep hygiene, the Jackson Heart Sleep Study, a sample of 785 people, found that either alcohol or nicotine use within 4 hours of bedtime was associated with poorer sleep quality, even when controlling for confounding factors like age, sex, education, BMI, depression, anxiety, stress, and having work or school the next day.

Light exposure and/or device use bash sleep.

Light exposure and/or device use bash sleep.

Whether we like it or not, we live in a digital age. Data is already emerging indicating that time spent on social media is time poorly spent but it appears that even the light emitted from our devices may be keeping the zzz’s at bay. A systematic review published in 2018 found that a 2-hour evening exposure to 460 nm wavelength (blue) light suppresses levels of melatonin, a key promoter of sleep onset and that prolonged exposure is associated with greater alterations in REM sleep. While restoration of melatonin levels occurs approx. 15 minutes after cessation of light exposure, it is unclear whether this alleviates sleep disruption. However, what’s more important is that a large proportion of light emitted from LEDs — which form many of our device screens — is blue light and systematic reviews and meta-analyses find that exposure to blue light is associated with higher alertness and decreased sleepiness and can decrease sleep quality and sleep duration (see here, and here, and here). Smartphone use specifically before bed also negatively impacts melatonin circadian rhythms and sleep quality (see here), although it is not certain whether this is specifically due to light exposure or the “stimulating” content viewed on the device. Yes, “night modes” exist but the actual beneficial effects of these settings are currently unclear. Whether the light or the device’s content is the culprit doesn’t really matter; why take the risk of killing your zzz’s and suppressing your exercise adaptations? So, go get some sleep and delay checking whether you bagged that Strava segment until the morning…

Even late evening high-intensity exercise can bash sleep.

Even late evening high-intensity exercise can bash sleep.

Some studies have indicated that exercise, particularly evening exercise, can alter the circadian rhythm of sleep possibly due to changes in core body temperature. However, the 2013 National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep in America study, a survey of 1000 people, found no association between self-reported sleep duration or quality and evening exercise of any intensity performed with 4-hours of bedtime. While a self-report survey does not disprove causality, a meta-analysis of 23 studies also indicated that light to moderate exercise within 4-hours of bedtime had no negative effect on sleep. Moderate-intensity (60% HRmax) running has even been shown to improve sleep quality but only when completed 4-hours before but not 2-hours before bedtime. However, the same meta-analysis also found that vigorous work-outs finishing within an hour of bedtime may impair sleep quality and duration while other work has also shown that vigorous exercise immediately before bedtime can delay sleep onset, when compared to moderate exercise or no exercise. Meanwhile, a 2021 meta-analysis found that high-intensity exercise performed 2-4-hours before bedtime does not disrupt sleep in healthy, young and middle-aged adults. Collectively, the data examining the timing between exercise and bedtime tell an interesting story. But it essentially indicates that if you’re gonna “hit it”, train earlier in the evening rather than later.

Caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, device light, and late-night exercise will interrupt sleep.

But how do you know if you are sleeping well or not? Well, there is no magic here. It is usually very clear when you have not slept well or have endured a period of poor or insufficient sleep. Ask any new parent how that feels. The gold standard measurement for sleep is polysomnography, which quantifies the physiological functions associated with sleep using electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG) and electrooculography (EOG). This approach allows for the accurate and precise measurement of sleep quantity, aka total sleep time, and sleep quality, as assessed by a cocktail of measurements including sleep onset latency (the time it takes to fall asleep), sleep maintenance, wakefulness after sleep onset (sleep interruption), total wake time, and sleep efficiency (the ratio between total sleep time and the total time in bed dedicated to sleep). However, polysomnography requires expertise and elaborate equipment, which nobody has at home.

There are lots of accelerometry-based devices and apps that aim to assess your sleep quantity and quality. Accelerometry performs fairly well for tracking sleep quantity but less so for quality. And, yep, there is also a condition, called orthosomnia, which is being preoccupied or concerned with improving or perfecting your sleep data from wearables, which do not accurately measure sleep cycles.

Instead of having a device tell you how long you slept and whether you slept or not, why not just go right to the root of sleep hygiene and optimise your sleep with simple fixes to your lifestyle:

Make sleep a priority! If you need to schedule sleep, put it on your “to-do list” and cross it off every morning. If you have time during the day for a nap, seize the opportunity (see here and go deep on napping here ).

Make sleep a priority! If you need to schedule sleep, put it on your “to-do list” and cross it off every morning. If you have time during the day for a nap, seize the opportunity (see here and go deep on napping here ).

Practice a sleep schedule. By adhering to a consistent sleep schedule, it will become a habit of daily living and will become deeply rooted in your lifelong mission to achieve recovery mastery.

Practice a sleep schedule. By adhering to a consistent sleep schedule, it will become a habit of daily living and will become deeply rooted in your lifelong mission to achieve recovery mastery.

Practice a relaxing pre-sleep ritual that you will habitually “associate” with going to bed. A ritual doesn’t necessarily mean listening to death metal and sacrificing a goat (unless that works) but find a ritual where you associate regular tasks with bedtime — association is a successful psychological tool for life-long habit-forming. My 10-minute ritual is to check my calendar, arrange tomorrow’s tasks, pee, brush my teeth, reflect on what I achieved today, and then go to bed. Some evidence also shows that a pre-sleep melatonin supplement can improve sleep quality and/or duration (here, here, here, here, and here). In addition, some people swear that taking a magnesium supplement or auditory stimulation (e.g. listening to white noise, pink noise, or binaural beats) as part of their pre-sleep ritual improves sleep quality, but the current evidence does not support the claims (see here, and here).

Practice a relaxing pre-sleep ritual that you will habitually “associate” with going to bed. A ritual doesn’t necessarily mean listening to death metal and sacrificing a goat (unless that works) but find a ritual where you associate regular tasks with bedtime — association is a successful psychological tool for life-long habit-forming. My 10-minute ritual is to check my calendar, arrange tomorrow’s tasks, pee, brush my teeth, reflect on what I achieved today, and then go to bed. Some evidence also shows that a pre-sleep melatonin supplement can improve sleep quality and/or duration (here, here, here, here, and here). In addition, some people swear that taking a magnesium supplement or auditory stimulation (e.g. listening to white noise, pink noise, or binaural beats) as part of their pre-sleep ritual improves sleep quality, but the current evidence does not support the claims (see here, and here).

Make bedtime comfortable and invest time and money in finding a mattress, duvet, and pillow that you love! Something I learned and embraced from my years living in Denmark is having a separate mattress, duvet, and blanket from the one with whom you share a bed. No more duvet hogging.

Make bedtime comfortable and invest time and money in finding a mattress, duvet, and pillow that you love! Something I learned and embraced from my years living in Denmark is having a separate mattress, duvet, and blanket from the one with whom you share a bed. No more duvet hogging.

Ensure that your bedroom is sleep-inducing: dark, silent, and cool. Black-out curtains, eye masks, earplugs, and turning the heat down a couple of degrees to cool the room, have all been shown to be effective for maintaining uninterrupted sleep. But possibly while ensuring that your feet are warm to speed up your sleep latency, as shown in a 2019 Nature paper.

Ensure that your bedroom is sleep-inducing: dark, silent, and cool. Black-out curtains, eye masks, earplugs, and turning the heat down a couple of degrees to cool the room, have all been shown to be effective for maintaining uninterrupted sleep. But possibly while ensuring that your feet are warm to speed up your sleep latency, as shown in a 2019 Nature paper.

Move your harder sessions as far away from your bedtime as possible. If possible, aim to do your harder workouts earlier in the day rather than super late and right before bedtime.

Move your harder sessions as far away from your bedtime as possible. If possible, aim to do your harder workouts earlier in the day rather than super late and right before bedtime.

Avoid cutting sleep to train more. More training needs more recovery not less - don’t shoot the messenger. If you have to train early in the morning, go to bed earlier to compensate and make that a normal habit. I was first exposed to the early morning exercise crowd in the US. Many of my colleagues and training partners would get up at 4 am (!!??!!) to get a workout done. Some of them went to bed early, while others simply just got up early. Guess which group was always tired at work and, if I am honest, not firing on all cylinders?

Avoid cutting sleep to train more. More training needs more recovery not less - don’t shoot the messenger. If you have to train early in the morning, go to bed earlier to compensate and make that a normal habit. I was first exposed to the early morning exercise crowd in the US. Many of my colleagues and training partners would get up at 4 am (!!??!!) to get a workout done. Some of them went to bed early, while others simply just got up early. Guess which group was always tired at work and, if I am honest, not firing on all cylinders?

Avoid caffeinated foods (chocolate, guarana) and beverages (tea, coffee, energy drinks, etc) in the late afternoon or evening and limit your daily caffeine intake to less than ≈400 mg per day (less than ≈4 cups of coffee). A recent meta-analysis found that to avoid reductions in total sleep time, your last cup of coffee should be consumed at least 8.8 hours before bedtime and a standard serve of “pre-workout” supplement should be consumed at least 13.2 hours before to bedtime! And, remember: caffeine is not a remedy for sleep deprivation.

Avoid caffeinated foods (chocolate, guarana) and beverages (tea, coffee, energy drinks, etc) in the late afternoon or evening and limit your daily caffeine intake to less than ≈400 mg per day (less than ≈4 cups of coffee). A recent meta-analysis found that to avoid reductions in total sleep time, your last cup of coffee should be consumed at least 8.8 hours before bedtime and a standard serve of “pre-workout” supplement should be consumed at least 13.2 hours before to bedtime! And, remember: caffeine is not a remedy for sleep deprivation.

Avoid drinking alcohol or using nicotine-containing products before bed. As an athlete, you are most likely not a smoker. If you do choose to smoke, make sure you are “on fire” down the closing straight to the finish line!

Avoid drinking alcohol or using nicotine-containing products before bed. As an athlete, you are most likely not a smoker. If you do choose to smoke, make sure you are “on fire” down the closing straight to the finish line!

Take a “digital detox” and reduce your screen time and blue-light exposure in the evening, eliminating it before bedtime. This includes minimising evening use of phones, tablets, laptops, computers, TV, etc. However, a cue with no action can make it hard to overcome a habit so you should consider replacing the device use with healthier habits, like reading a book, writing a journal, or practising some mindfulness, which has been shown to help improve sleep quality. Plus, based on the current evidence, it is not clear whether blue-light filtering glasses do anything to reduce the sleep-bashing effects of blue light exposure; so, don’t waste our money on an expensive pair of glasses just yet.

Take a “digital detox” and reduce your screen time and blue-light exposure in the evening, eliminating it before bedtime. This includes minimising evening use of phones, tablets, laptops, computers, TV, etc. However, a cue with no action can make it hard to overcome a habit so you should consider replacing the device use with healthier habits, like reading a book, writing a journal, or practising some mindfulness, which has been shown to help improve sleep quality. Plus, based on the current evidence, it is not clear whether blue-light filtering glasses do anything to reduce the sleep-bashing effects of blue light exposure; so, don’t waste our money on an expensive pair of glasses just yet.

And, one last tip…

Don’t lie in bed awake, instead, do something calming. Associate being in bed with being asleep. If you can’t sleep, lying there worrying about not sleeping will keep you awake. Instead, get up and do something calm, like reading a book, until you feel tired. But avoid exposing yourself to a “stimulant” like a light-emitting device.

Don’t lie in bed awake, instead, do something calming. Associate being in bed with being asleep. If you can’t sleep, lying there worrying about not sleeping will keep you awake. Instead, get up and do something calm, like reading a book, until you feel tired. But avoid exposing yourself to a “stimulant” like a light-emitting device.

This sleep hygiene toolkit is derived from the above-described evidence, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the evidence (e.g. here, here, and here), guidelines issued by the National Sleep Foundation, and general recommendations made for athletes.

Using this sleep hygiene toolkit will help you become a Jedi master of your sleep, which is important because epidemiological data shows that being in control of your sleep is strongly associated with longer sleep duration and enhanced sleep quality. But please remember, if your sleep issues are persistent and you are constantly sleepy or fatigued, finding it hard to stay alert, or have leg cramps/tingling/breathing difficulties at night, then take action and consult your doctor or seek a medical-doctor-led sleep clinic immediately. They will be able to determine the underlying cause and help you be the best you.

Optimise your sleep hygiene to achieve long and uninterrupted nightly sleep.

Optimise your sleep hygiene to achieve long and uninterrupted nightly sleep.

Identify and address possible factors that could be hindering your zzz time.

Identify and address possible factors that could be hindering your zzz time.

Assess the impact of improving sleep hygiene on your athletic performance.

Assess the impact of improving sleep hygiene on your athletic performance.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. This was a long but important session, from which some recovery will be needed. Until next time, sleep well to train smart.

But what is sleep?

Since we do it so much, we are all “sleep experts”, right? You lie down, you close your eyes, and your brain turns “off”. Hell no. While your heart rate and blood pressure drop to resting levels, your sleeping metabolic rate is not equal to zero. Far from it. Your metabolic rate will be somewhere in the region of 1 kcal per minute, which means that during 8-hours of zzz’s, you will expend around 500 kcals. That is equivalent to running at a moderate effort, say your marathon pace, for about 30 minutes. Your body may be relatively motionless but while you sleep, your heart is pumping, your lungs are inflating, and your brain is throwing shapes like a raver at the Hacienda in the 90s. Basically, the Chemical Brothers, ATP and ADP, are “cycling” like crazy.When you are getting your zzz’s, your brain “runs” through a cycle of stages. Stage 1 is very short and is a light sleep, a cat nap, during which you are still alert and can easily be woken. Stage 2 is also pretty light but is characterised by a sudden increase in the frequency of brainwave activity followed by a “slowing down”. Stages 3 and 4 are your deep sleep where muscles and tissues grow, develop, and repair, and immune function is improved. There is no eye movement or muscle activity during these phases and it is very difficult to be woken. Then there is a rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep, during which your brain activity spikes, you dream, your eyes “dance”, and your heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate increase. REM sleep first occurs about 90 minutes after initially falling asleep but you may have 5 or 6 REM cycles per night, each lasting up to an hour. During REM, you will be learning and developing memories, and consolidating new information so it can be stored in the long-term filing cabinet. These stages are measurable using electroencephalography (EEG), which detects waves of electrical activity in your brain. As Michael Stipe would say, “what’s the frequency, Kenneth?”

×

![]()

When you fall asleep, your brain cycles through these stages sequentially. Just like all living organisms, we have a circadian rhythm, a natural sleep-wake cycle that is dictated by our biological clock genes. Our circadian rhythm runs on a 24-hour clock. Very much like plants, which raise their leaves to “open their eyes” at opportune times of the day, your sleep-wake cycle is synchronised with environmental cues, like light and temperature. Your circadian rhythm and the cycling of your sleep stages are regulated by neurotransmitters and hormones, including a whole bunch of fun folks: γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and adrenaline (epinephrine), orexin, acetylcholine, histamine, cortisol, melatonin, and serotonin. As you might notice, several of these are also regulated by exercise, which might explain the emergence of recent exercise-circadian timing studies. Your sleep may seem simple but, during sleep, your brain is a complex beast. Fortunately, you don’t need to think too much about when to sleep because your brain does a wonderful job of regulating it. When you need sleep, sleep. Don’t fight it.

Why do you need sleep?

For a fun dig into the biology, I can recommend the book “Why we sleep”, by Dr Matthew Walker, director of the Centre for Human Sleep Science. While he has upsold and elaborated some aspects of his research, the book will make you appreciate the importance of sleep and, as I found, will likely make you delve deeper into the evidence. So, for an excellent overview of the metabolic consequences of sleep and lack thereof, I can recommend a review published in Sleep Med in 2008 by Dr Eve van Cauter.Without regurgitating 50-years of research, I will keep this simple. During sleep, the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through your brain increases, helping to provide more oxygen, nutrients, and hormones to neurons, removing metabolic products, and sending signalling molecules to other parts of your body. All stages of sleep are important, which is why prolonged and uninterrupted sleep is essential. As well as helping to regulate appetite and energy balance, with specific relevance to exercise recovery, accumulating sufficient amounts of uninterrupted sleep each night allows you to:

and,

Despite the immense dedication to understanding the neurobiology of sleep and its consequences, we still do not really know “why we sleep”; after all, many animals do not sleep in the way that we do. But sleep does appear to be an evolutionary tool that enables animals to hunt, gather, reproduce, resist infection, and fight. I.e., sleep will keep your physiological, psychological, reproductive and immunological health as sharp as the tools we once carved out of rock. Although life is slightly different for modern-day humans, you may have noticed that after one or two nights of poor or interrupted sleep, once seemingly easy tasks simply become awkward and frustrating. Yep, sleep is needed to prevent you from becoming a mental and physical shipwreck. No one enjoys a shipwreck.

×

![]()

But, how much sleep do you need?

The amount of sleep we require is dependent on the growth stages of life and, therefore, changes with age. For example, newborns (0-3 months) require 14 to 17 hours each day, school-age children (6-13 years) require 9 to 11 hours each day, and teenagers (14-17 years) need around 8 to 10 hours. As we age, especially beyond 60 years of age, the duration and depth of our sleep decrease and the number of nightly interruptions to our sleep increases. This is a normal part of ageing.For those of us aged 18 and older, the days of epic sleep are behind us, but the recommendations from the National Sleep Foundation are that we require

If you are highly active, the amount of sleep you need is likely higher, but the truth in that is not completely certain. Recent work found that elite athletes need about 8-hours sleep a night to “feel” rested and that 71% of athletes fail to meet this need on most nights. Due to a lack of research, there are no specific sleep guidelines for athletes and it is not known whether athletes actually need more sleep. Nonetheless, as I will get to if you stay with me on this journey, sleep restriction is not an athlete’s friend and sleep extension is so special it should be embraced at any opportunity. Any athlete, even a wise old master’s athlete in whom natural sleep duration and depth may be shortening, should be doing their best to sleep as much and as well as they can.

To summarise that rant, although “sleepiness”, the “propensity to fall asleep” and the “need for sleep” are not identical concepts, one thing is clear: we humans need sleep. Consequently, for you athletes, there is one burning question... is sleep the power tool you need in your athletic performance toolbox?

Sleep restriction will likely impair your performance.

Now you know that sleep maintains your physiological, psychological, and immunological health and that sleep consolidates information to help you embed memories and learn new skills, the importance of sleep for athletic success begins to emerge from the clouds. So, what happens when you cut your daily dose of sleep?Several studies convincingly show that acute (1-night) and chronic (several days) reduction in nightly sleep decreases cognitive performance in athletes, including poorer reaction times, psychomotor vigilance, and sequence recognition. The recovery of impaired cognitive performance following sleep restriction in athletes also takes much longer when sleep has been impaired chronically. Sleep restriction also has a profound effect on reducing mood and motivation. We might speculate that this will also impair physical performance but, rather than making assumptions, let’s dig into the actual data…

A single night of complete sleep deprivation has been found to reduce muscle protein fractional synthetic rate in healthy men and women. This observation was found coupled with increased cortisol (a stress hormone) and reduced testosterone (an anabolic steroid hormone) levels in the blood. Sleep restriction (4 hours/night for 5 nights) in healthy and active young men also reduced myofibrillar protein synthesis (which may explain sleep-deprivation induced loss of muscle mass) but only in the absence of daily exercise. Sleep restriction can also modify the utilisation of metabolic fuel switching during periods of weight management. For example, it has been shown in overweight men and women that 2 weeks of moderate calorie restriction combined with normal or restricted nightly sleep led to the same weight loss (~3 kg) but having just 5.5-hours of sleep/night caused less fat loss and more fat-free mass loss compared to 8-hours/night. Further work has found that a single night's loss of sleep in young, healthy men and women caused genome-wide changes in DNA methylation that were coupled with metabolic biomarkers indicative of potential for muscle tissue breakdown and adipose tissue expansion, plus a decrease in glycolytic enzyme expression in muscle, changes in muscle clock genes, and increments in muscle inflammation. Lots of mayhem. Lots of potential for muscle dysfunction.

These above-described studies examined physiological measurements that might affect recovery and performance. But, what about actual performance?

Let’s do this!

Immediately following a single night of sleep deprivation, it has been shown in young college athletes that reaction times are delayed but peak cycling power is unaffected. However, in young male runners, 1-night of sleep deprivation has been shown to decrease treadmill endurance performance during a “run as far as you can in 30-minutes” test, with no change in RPE. Similarly, in male team-sports athletes, 1-night of sleep deprivation impaired mood, decreased muscle glycogen levels, and reduced shuttle running speed, when compared to data collected after normal habitual sleep. In relation to muscle strength, 1-night of sleep deprivation had an immediate negative effect on mood state followed by a loss of muscle strength the following day, in young males. In accordance with this “delayed” impairment in strength, peak torque during knee extension and flexion was reduced in US Marines, 2-days following a single night of sleep deprivation.

More extreme but less relevant periods of sleep deprivation have also been examined. Vertical jump height decreased following 64 hours of sleep deprivation in young male subjects but only when they were inactive and not engaging in intermittent exercise, which prevented the loss of jump height induced by this extreme sleep deprivation. In a separate study, 48 hours of sleep deprivation in young male athletes who underwent eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage did not affect the restoration of muscle strength when compared to 2-days of their normal habitual sleep. But, blood levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-6, and IGF-1, cortisol, and cortisol/total testosterone ratio were higher following 48-hours of sleep deprivation.

The effects of consecutive night sleep reduction have also been examined. In recreational weightlifters, sleep deprivation to 3 hours/night for 3 nights decreased mood and increased sleepiness and confusion after just 1 night and, after the second night, maximal and submaximal lifting ability was reduced and RPE increased. While in elite cyclists, 3 nights of 4 hours/night of sleep reduced maximal jump height and response time while impairing coordination during multiplanar tests when compared to test scores following their habitual 7.5 hours of sleep/night.

To summarise, it seems that maximum power is not affected immediately following 1-night of sleep restriction but is smashed the next day, while the effects on sub-maximal work are more immediate. Sports that require speed, tactical strategy, and technical skill are most sensitive to acute sleep deprivation while the effects on endurance manifest with repeated sleep deprivation. Of course, different study designs and between-subject variability in the outcomes are evident but because strength, endurance, strategy, and skill are the key to endurance success, the overall message is, to maintain your athletic abilities, don’t squash your sleep. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses now confirm that sentiment (see here, here, here, and here).

What’s the opposite of restriction? Extension… Sleep extension will likely improve your performance.

Since insufficient research exists, it is not known whether athletes actually need more sleep. While there are no specific guidelines, it is clear that sleep deprivation decreases mood and alertness in athletes while sleep extension increases these variables. While such outcomes might affect recovery, they are not performance outcomes. But, as I will now summarise, sleep extension studies in athletes have shown profound effects on performance. One large study had 70 nationally-ranked athletes rate their feelings of fatigue prior to each workout for 2-weeks. The authors found that greater total sleep duration was associated with lower levels of pre-session fatigue. Furthermore, they reported that early-morning workouts (between 5 and 6 am) reduced sleep duration (to ~5 hours/night, i.e. they didn’t go to bed earlier) and increased pre-session fatigue and that the later a workout was, the longer athletes stayed in bed and felt less fatigued before their sessions. While this is just a correlation that does not prove causality to performance, fortunately, experimental studies have toyed around with sleep duration and examined the opposite of sleep restriction. So, what happens when you throw a bunch of extra zzz’s at athletes?A 6-night period of sleep extension (~2-additional hours per night) prior to 1-night of total sleep deprivation lowered RPE during knee extensor exercise (submaximal voluntary contraction to fatigue) and prevented the sleep deprivation-induced reduction in time to fatigue, in young healthy men. These findings show that sleep extension before sleep restriction can help maintain neuromuscular function and are relevant to ultra races, many of which start in the middle of the night and continue until the next night, deleting one night of sleep. A planned period of sleep extension before an ultra race or a race that starts in the middle of the night may be a useful tool to help keep your motor control in check and your neurons firing just enough to keep you sharp. I have never raced an ultra but I have raced many marathons, completed a few training runs in and around the 30-mile mark, and regularly do 3 to 5 hour runs in the mountains. I have also played around with doing hard sessions off different amounts of sleep and at different times of the day and night. The clear pattern is that at the end of super loooong effort, not everything upstairs is working with 100% clarity, even if I have been well-fed; a hard session following a night of sleep deprivation does not proceed with grace; and, a hard session in the middle of the night just feels weird and wrong. It is wrong; one should be in bed.

A similar duration of sleep extension, 2-additional hours per night for 1-week, lowered sleepiness and increased the accuracy of serves in a small group of college-level tennis players. A longer-term period of sleep extension has also been examined in male college basketball players, where 6 weeks of sleep extension, aiming for 10 hours in bed (approx 2-additional hours sleep per night ), reduced sleepiness, increased mood, and improved sprint times and shooting accuracy. However, this study had no control group (sigh...) so improved performance due to 5-7-weeks of training adaptations cannot be ruled out.

Now, submaximal knee extensor contraction-to-failure, serving accuracy, and shooting accuracy may not seem relevant to endurance performance. You are correct; the external ecological validity is indeed poor. But, resisting neuromuscular fatigue is critical for endurance success and improved skill is one of the things that helps improve running economy. And, any obstacle racer will get shivers down their spine when they visualise the consequence of an inaccurate and missed spear throw. Extrapolation is nice but what about some hard evidence?

In 2019, investigators at Deakin University used a cross-over design to examine the effects of 3-nights of habitual (7 hours/night) vs. restricted (5 hours/night) vs. extended (9 hours/night) sleep on endurance performance, in trained male cyclists and triathletes. Sleep restriction impaired mood, psychomotor vigilance (cognitive reaction time), and time-to-completion in a cycling time-trial while sleep extension improved cognitive performance and endurance performance, when compared to habitual sleep. Interestingly, no changes in RPE were found suggesting that sleep extension enabled athletes to think quicker and ride faster at the same level of effort. Perhaps this sounds like a tool you’d like to be armed with during your next race.

As I said above, the recommended amount of daily sleep for adults is 7 to 9 hours and if you are highly active, the amount of sleep you need is likely higher. Whether or not highly-active people need more sleep than regular folks is uncertain. BUT, the emerging data clearly indicate that increasing your daily amount of sleep will enhance your recovery to go again. And, as Adharanand Finn noted in his book, Running with the Kenyans, the finest African athletes that we all admire, sleep a lot — just lounging around when not training and napping when they get bored of lounging. Perhaps sleep is one of the mightiest “power tools” in a world-class recovery toolbox. But, what can you be doing to help yourself recover like a pro?

Use it!

×

![]()

Note: For a thorough overview of the role of sleep in athletes not only in relation to exercise performance but also neurocognitive performance, injury, illness, and well-being, scientists at the Stanford School of Medicine conducted a systematic review of the literature: Optimizing sleep to maximize performance: implications and recommendations for elite athletes, as did a group of scientists at UT Sydney: Sleep and Athletic Performance: The Effects of Sleep Loss on Exercise Performance, and Physiological and Cognitive Responses to Exercise. I can also recommend a 2019 review published in Int J Sports Med, Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations.

Aim for sleep hygiene: quantity and quality.

Sleep allows recovery from the previous wake cycle and prepares the body for the subsequent wake cycle. Sleep is your “rest interval” between the days of life; the longest interval session you ever engaged in. Sleep is essential for maintaining high power output during the daytime efforts. Just like your interval sessions where the duration and quality of your rest-intervals dictate the overall load (stress) of the session, the duration and quality of your sleep influence the quality of life. The amount of sleep you get is positively correlated with many things including increased well-being (happiness) and reduced disease risk. However, increased interruptions to sleep negate the beneficial effects of sleep and thwart the quality of the stages of sleep.Sleep is awesome; sleep hygiene is essential. If you are not achieving your 7- to 9-hours of sleep per night, or if you are having difficulties falling asleep, or if you experience frequent interruptions to your sleep, do you ever wonder why? Besides excess light, noise, and high temperatures, some of your favourite things are also fuel for the night devil who keeps you awake...

Among the studies that have found negative effects of drinking and smoking on sleep hygiene, the Jackson Heart Sleep Study, a sample of 785 people, found that either alcohol or nicotine use within 4 hours of bedtime was associated with poorer sleep quality, even when controlling for confounding factors like age, sex, education, BMI, depression, anxiety, stress, and having work or school the next day.

Whether we like it or not, we live in a digital age. Data is already emerging indicating that time spent on social media is time poorly spent but it appears that even the light emitted from our devices may be keeping the zzz’s at bay. A systematic review published in 2018 found that a 2-hour evening exposure to 460 nm wavelength (blue) light suppresses levels of melatonin, a key promoter of sleep onset and that prolonged exposure is associated with greater alterations in REM sleep. While restoration of melatonin levels occurs approx. 15 minutes after cessation of light exposure, it is unclear whether this alleviates sleep disruption. However, what’s more important is that a large proportion of light emitted from LEDs — which form many of our device screens — is blue light and systematic reviews and meta-analyses find that exposure to blue light is associated with higher alertness and decreased sleepiness and can decrease sleep quality and sleep duration (see here, and here, and here). Smartphone use specifically before bed also negatively impacts melatonin circadian rhythms and sleep quality (see here), although it is not certain whether this is specifically due to light exposure or the “stimulating” content viewed on the device. Yes, “night modes” exist but the actual beneficial effects of these settings are currently unclear. Whether the light or the device’s content is the culprit doesn’t really matter; why take the risk of killing your zzz’s and suppressing your exercise adaptations? So, go get some sleep and delay checking whether you bagged that Strava segment until the morning…

Some studies have indicated that exercise, particularly evening exercise, can alter the circadian rhythm of sleep possibly due to changes in core body temperature. However, the 2013 National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep in America study, a survey of 1000 people, found no association between self-reported sleep duration or quality and evening exercise of any intensity performed with 4-hours of bedtime. While a self-report survey does not disprove causality, a meta-analysis of 23 studies also indicated that light to moderate exercise within 4-hours of bedtime had no negative effect on sleep. Moderate-intensity (60% HRmax) running has even been shown to improve sleep quality but only when completed 4-hours before but not 2-hours before bedtime. However, the same meta-analysis also found that vigorous work-outs finishing within an hour of bedtime may impair sleep quality and duration while other work has also shown that vigorous exercise immediately before bedtime can delay sleep onset, when compared to moderate exercise or no exercise. Meanwhile, a 2021 meta-analysis found that high-intensity exercise performed 2-4-hours before bedtime does not disrupt sleep in healthy, young and middle-aged adults. Collectively, the data examining the timing between exercise and bedtime tell an interesting story. But it essentially indicates that if you’re gonna “hit it”, train earlier in the evening rather than later.

×

![]()

As you can see, there are a number of components of your daily living that can throw a dirty blanket over your sleep hygiene. So, the next obvious thing is to ask yourself...

What can you do to “cleanse” your sleep? Maximise your sleep “hygiene” to optimise your recovery.

The world is full of stimulants - coffee, cigarettes, energy drinks, external light, electronic devices, LOUD NOISES, and the “fear of missing out” fuelled by social media. These stimulants interfere with our circadian rhythm, our natural sleep-wake cycle. Therefore, it might seem obvious that paying attention, moderating, and limiting exposure to these stimulants is prudent for optimising sleep hygiene.But how do you know if you are sleeping well or not? Well, there is no magic here. It is usually very clear when you have not slept well or have endured a period of poor or insufficient sleep. Ask any new parent how that feels. The gold standard measurement for sleep is polysomnography, which quantifies the physiological functions associated with sleep using electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), electromyography (EMG) and electrooculography (EOG). This approach allows for the accurate and precise measurement of sleep quantity, aka total sleep time, and sleep quality, as assessed by a cocktail of measurements including sleep onset latency (the time it takes to fall asleep), sleep maintenance, wakefulness after sleep onset (sleep interruption), total wake time, and sleep efficiency (the ratio between total sleep time and the total time in bed dedicated to sleep). However, polysomnography requires expertise and elaborate equipment, which nobody has at home.

There are lots of accelerometry-based devices and apps that aim to assess your sleep quantity and quality. Accelerometry performs fairly well for tracking sleep quantity but less so for quality. And, yep, there is also a condition, called orthosomnia, which is being preoccupied or concerned with improving or perfecting your sleep data from wearables, which do not accurately measure sleep cycles.

Instead of having a device tell you how long you slept and whether you slept or not, why not just go right to the root of sleep hygiene and optimise your sleep with simple fixes to your lifestyle:

And, one last tip…

Using this sleep hygiene toolkit will help you become a Jedi master of your sleep, which is important because epidemiological data shows that being in control of your sleep is strongly associated with longer sleep duration and enhanced sleep quality. But please remember, if your sleep issues are persistent and you are constantly sleepy or fatigued, finding it hard to stay alert, or have leg cramps/tingling/breathing difficulties at night, then take action and consult your doctor or seek a medical-doctor-led sleep clinic immediately. They will be able to determine the underlying cause and help you be the best you.

What can you add to your training toolbox?

Sleep is your ally in living a long and healthy life. Sleep is also a requisite to help you recover from and optimally adapt to your training, getting you ready to go again. The bottom line is that for any organism that sleeps, sleep is important. Get as much sleep as you can. Even if you think you don’t need sleep, just get as much of it as you can - too little sleep will harm you, too much sleep won’t. Don’t overcomplicate it. For any human who has cognitive or physical performance goals, sleep is a power tool to keep nestled in your toolbox. Keep that tool well-sharpened and ready to use. So,Thanks for joining me for another “session”. This was a long but important session, from which some recovery will be needed. Until next time, sleep well to train smart.

Feel free to use and share this figure but please give credit to Thomas PJ Solomon PhD.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and new craft beers that send my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and new craft beers that send my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.