Education for runners and endurance athletes. Learn to train smart, run fast, and be strong.

These articles are free.

Please help keep them alive by buying me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

This article is part of a series:

→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Recovery for runners and endurance athletes.

→ Part 1 — Eat, sleep, rest, repeat.→ Part 2 — Sleep.

→ Part 3 — Naps.

→ Part 4 — Rest.

→ Part 5 — Nutrition.

→ Part 6 — Magic.

→ Part 7 — How to recover.

→ The Recovery Magic Tool

Sleep will supercharge your recovery. But what about napping and your chronotype?

Thomas Solomon PhD.

17th Jun 2020.

It is clear that sleep is a power tool you must possess in your exercise recovery toolbox. But of course, there are some caveats to your zzz’s that need addressing. In this session, I will delve into the sleep-related world of things cats like to do and the various brands of body clocks.

Reading time ~10-mins (2000-words)

Or listen to the Podcast version.

Or listen to the Podcast version.

After my recent deep-dive into sleep, you are hopefully now very well-versed as to how a lack of sleep will retard your physical performance and how adding just a few more nightly zzz’s will make you a race day hero. Perhaps you have even begun spring-cleaning your sleep hygiene to help develop superpowers to get yourself ready to go. However, in the interest of keeping things generalised, I avoided two rather important topics that you are no doubt very well aware of. The first is a simple concept - all cats love it, some humans love it, and others hate it: napping. The second is vastly more complicated: your chronotype; the genetically-determined sleep-wake cycle of your circadian rhythm.

Interviews, books, and conversations with world-class athletes often indicate that they like and even need to nap. Documentaries about Kenyan athletes in their training camps in Iten often portray lots of lounging around and napping in huts in between sessions. Indeed, Adharanand Finn’s book, Running with the Kenyans, mentions that these running Gods can sleep up to 14-hours a day. However, most world-class elite athletes are professional athletes who can generally spare time during the rest intervals between sessions to take naps if they feel sleepy. Mere mortals, meanwhile, may not have such opportunities for naps due to work commitments and social pressures, not to mention the very likely possibility of unruly kids running around creating chaos.

If the opportunity is gracefully bestowed on you, a nap is a deliberate period of sleep lasting from three minutes to three hours. Napping is massively variable among us humans. Some folks love a good ole nap, while others do not. The science behind napping shows that we either need to nap (restorative napping) or simply just like to nap (appetitive napping), but the reasons have recently been elaborated to include dysregulative napping, mindful napping, and emotional napping, with only the latter found to be negatively associated with well-being. To very briefly summarise what we know about napping, the good news is that napping is not necessarily a sign that your sleep debt is accumulating interest, non-emotional napping won’t destroy you, and some types of naps, like mindful napping, actually rests your body and your mind. That sounds pretty solid and might indicate that napping should be embraced, right? Well, let’s dig a bit deeper...

The effects of napping on cognitive performance have been vastly studied. Napping can restore alertness after a single night of sleep loss but not after two nights. Napping can also improve alertness and computer task performance in night-shift workers and healthcare workers. But there is a caveat. These studies also show that the outcomes of napping are influenced by the time of day and the duration of the nap and, especially, the stage of sleep people reach during their naps. Looking ahead, the science of napping needs to unravel somewhat. So perhaps, for now, just sleep on it.

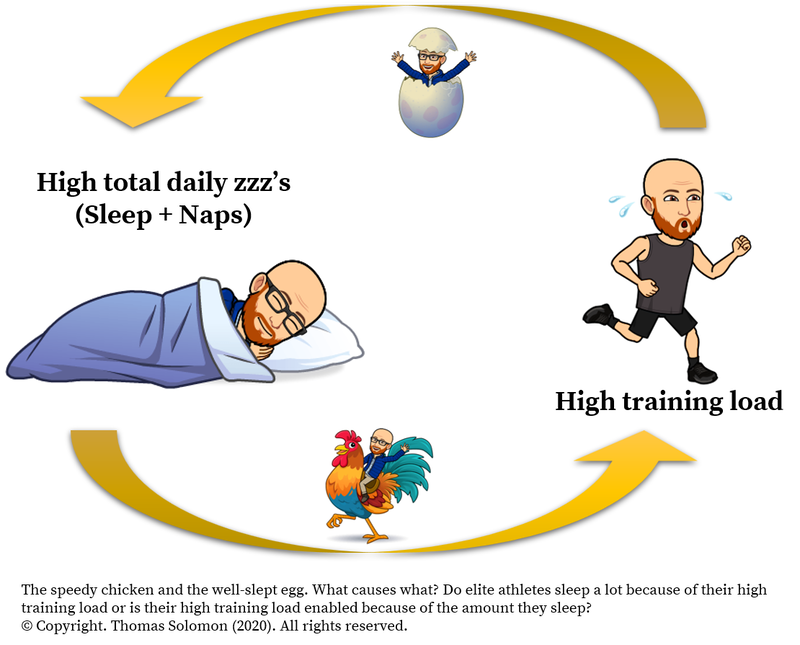

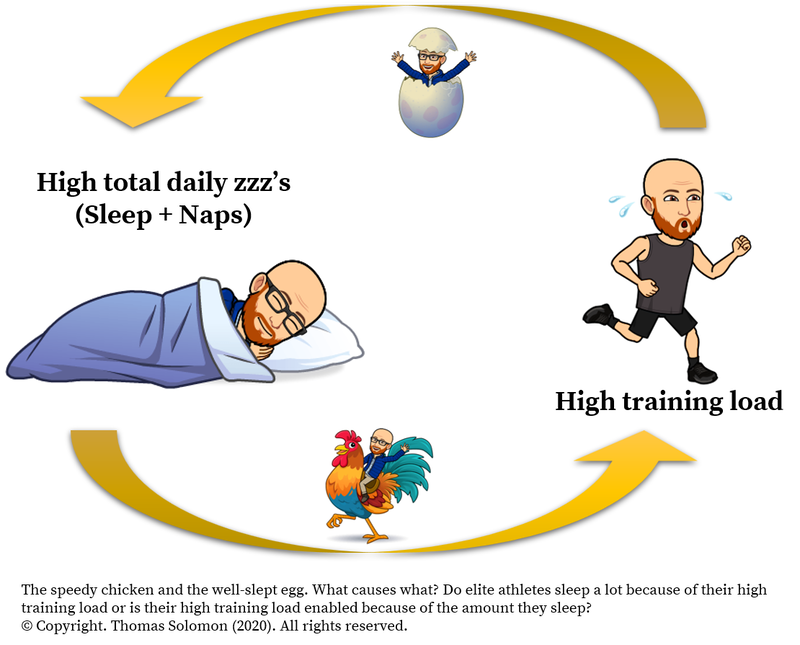

Although cognition feeds into how your body can perform, measuring cognitive performance outcomes is very different from markers of physical performance. The findings just described should not automatically be extrapolated to your athletic prowess. What do we know about napping in athletes? Well, not much actually... In a cross-sectional comparison of non-athletes, sub-elite athletes, and international-level elite athletes, the elite athletes were simply better at taking naps on-demand than sub-elite and non-athletes; i.e. they had greater “sleepability”, and napping was associated with shorter sleep latency at night, i.e. a better ability to fall asleep once in bed. The comparison also found that napping was not related to nocturnal sleep disruption or daytime sleepiness. So, if elite athletes nap and they are awesome at their craft, should everyone be napping? Well, even though this was a robust study that used polysomnography, the gold standard tool for examining sleep duration and quality, correlation and causality are seldom aligned. Are elite athletes elite because they sleep, or do they sleep and/or nap more because they are engaged in the high training load of an elite athlete? Who is the chicken; who is the egg?

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

Nearly 50% of the variability in being a lark or an owl is inherited in the genes gifted to you by your parents. Being male increases the probability that you are an owl while women are more likely to have a morning chronotype. Furthermore, the tendency to be an owl decreases with advancing age after adolescence. While your chronotype is influenced by genetics, sex, and age, it is very important to remember that the minimum recommended amount of sleep you need for maintaining optimal function stays the same: at least 7 to 9-hours a night, in adults (more in adolescents, children and new-borns).

There are a handful of people on Earth who truly only need small amounts of sleep each night. But, this is exceptionally rare. I have met many athletes who think they don’t need much sleep. But, is it a coincidence that such folks have, without exception, always appeared to be in need of more sleep? They are always tired, constantly injured, sometimes short-tempered, and never adapting and improving their performance as expected. If you are highly active, you probably need more sleep. I say probably because it is not completely known whether athletes need more sleep. But, in my recent post on sleep, I got under the covers with a bunch of sleep extension studies showing that athletes who sleep more, perform better. Win-win.

It is also not explicitly clear how athletes with different chronotypes are affected by different types of sleep patterns. Anecdotally, if my wife, an “owl”, attempts to get up early with her late chronotype, she stumbles around on the trails for a few hours like a zombie who has forgotten she likes to eat braaains. If she gets to bed late and lies in, she’s a hoot. I, on the other hand, am endowed with an early chronotype. Bed at ten, eyes open at six, ready to sing like a bird and start “larking” around in the mountains. If I go to bed late, I wake up feeling like I might well have sunk 9-bottles of imperial porter and rocked my socks off at Glastonbury before attempting some kind of session. While these are sentiments you may relate to, they are simply anecdotes. To understand how training adaptations and performance outcomes are regulated in people with different chronotypes and how different sleep patterns might interact with such outcomes, we must consider experimental evidence.

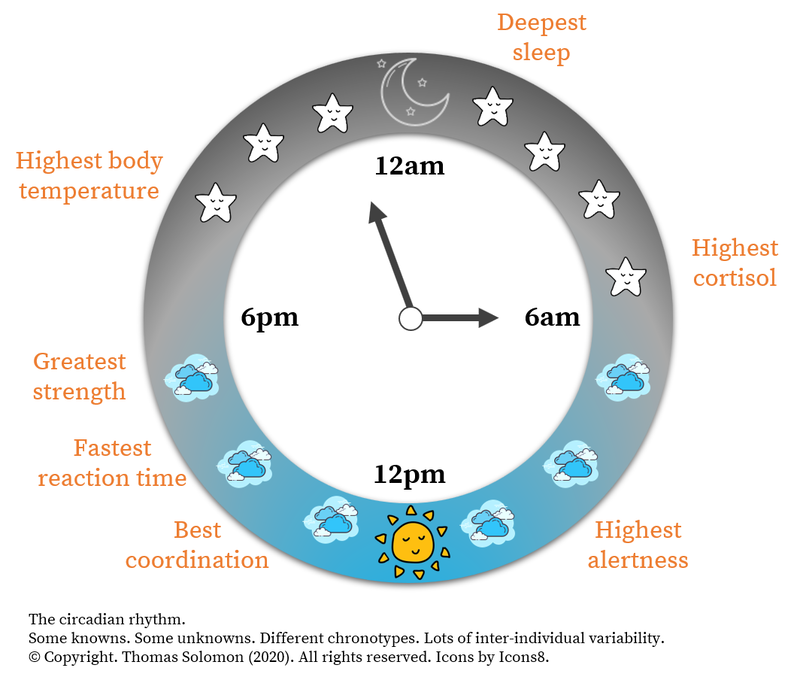

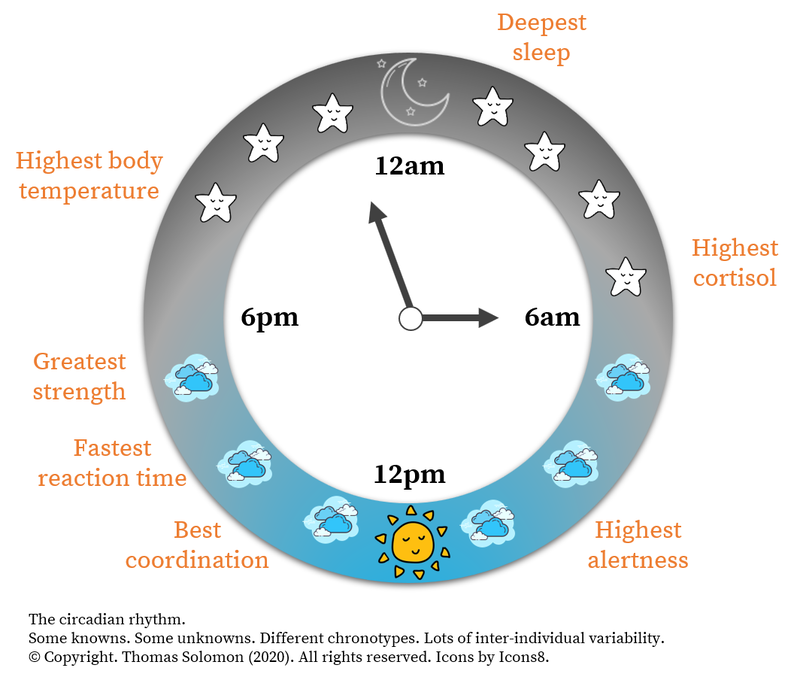

Chronotypes generally display peaks of several psychological and physiological variables at times corresponding to your owl-ness or lark-ness. Two key variables that have relevance to exercise performance and that also display a circadian rhythm in line with your specific sleep-wake cycle, are plasma cortisol levels and core body temperature. Cortisol tends to peak as you wake up while your body temperature typically peaks before you go to sleep. Since elevated cortisol or elevated body temperature can each cause premature fatigue and are associated with impaired exercise performance, it is tempting to speculate that chronotype may have relevance to training and athletic performance.

To address this speculation. A 2015 systematic review of 113 published articles concluded that technical skills in sports like badminton, tennis, and soccer, peak earlier in the day, typically in the afternoon; while muscle strength and anaerobic performance typically peak in the early evening. In general, the authors found that athletic performance was consistently better in the evening/afternoon than the morning, for all sports. However, this review did not specifically examine studies of athletes with different chronotypes. Fortunately, in 2017, Dr Jacopo Vitale published a systematic review in Sports Medicine examining just that. The review indicated that athletes with morning chronotypes (larks) were found to feel less fatigue, have a lower RPE, and have the fastest race times in the morning for half- and full-marathons, as well as 2000-metre rowing time trials, and 200-metre swimming time-trials, when compared to athletes with other chronotypes. Furthermore, evening-chronotype athletes (owls) needed more time to be “ready to go” after waking up than morning-chronotypes. This transition time between sleep and wakefulness is known as “sleep inertia”, which presents itself through the medium of disorientation and motor coordination. Upon waking, sleep inertia is more extreme in owls than it is in morning-chronotype larks.

Another aspect to consider is how your sleep hygiene may be affected by a late-evening workout. A recent experimental study from Dr Vitale found that sleep quality, after an evening session of S.H.I.T. (short high-intensity interval training), was poorer in morning-chronotype soccer players when compared to evening-chronotype players. Furthermore, there were no differences in sleep quality between the two chronotypes when the S.H.I.T. was taken in the morning.

To summarise, the research to date indicates that larks have a performance advantage over owls. Since the vast majority of races occur in the morning, this may favour early chronotype athletes. However, owls’ sleep may be less affected following an intense workout than larks, offering late chronotypes more time-flexibility in their training with respect to sleep quality. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the current studies are few and far between and there is considerable inter-individual variability in performance outcomes between subjects. Also, importantly, it remains to be examined whether chronotype can be “trained” and, therefore, changed to help one adjust to racing at times of the day when you’d rather be singing like a lark or hooting like an owl. Watch this space, as I am sure scientists will go down that path very soon...

Image Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

The recommendation is to sleep a minimum of 7 to 9 hours a night. As an athlete, you may need more and the evidence certainly suggests that sleeping more will increase your physical performance. As I frequently remind people, you are the only you. Learn to understand your natural sleep habits. Assess your own individual need for sleep and compare your mood, vigour, and performance after periods of poor versus great sleep. If you need to nap, nap, but prioritise identifying the areas where you could improve your sleep hygiene to maximise the quantity and quality of your nightly zzz’s. For now, don’t waste valuable energy stressing over or trying to toy with your chronobiology because not enough is known about how to optimise your training based on your chronotype.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. Bye for now and, whether you like to sing like a lark or hoot like an owl, get your sleep hygiene in order to keep your engine roaring like a lion.

Will taking a nap improve your recovery and performance?

What do students, parents with newborns, and world-class athletes all have in common? They all often report that they nap, a lot! World-class athletes who are also studying and raising a baby; I salute you. If there was ever a high-pressure, high-stress situation that requires all of your cunning to stay fresh and physically and cognitively “on it”, then this is it.Interviews, books, and conversations with world-class athletes often indicate that they like and even need to nap. Documentaries about Kenyan athletes in their training camps in Iten often portray lots of lounging around and napping in huts in between sessions. Indeed, Adharanand Finn’s book, Running with the Kenyans, mentions that these running Gods can sleep up to 14-hours a day. However, most world-class elite athletes are professional athletes who can generally spare time during the rest intervals between sessions to take naps if they feel sleepy. Mere mortals, meanwhile, may not have such opportunities for naps due to work commitments and social pressures, not to mention the very likely possibility of unruly kids running around creating chaos.

If the opportunity is gracefully bestowed on you, a nap is a deliberate period of sleep lasting from three minutes to three hours. Napping is massively variable among us humans. Some folks love a good ole nap, while others do not. The science behind napping shows that we either need to nap (restorative napping) or simply just like to nap (appetitive napping), but the reasons have recently been elaborated to include dysregulative napping, mindful napping, and emotional napping, with only the latter found to be negatively associated with well-being. To very briefly summarise what we know about napping, the good news is that napping is not necessarily a sign that your sleep debt is accumulating interest, non-emotional napping won’t destroy you, and some types of naps, like mindful napping, actually rests your body and your mind. That sounds pretty solid and might indicate that napping should be embraced, right? Well, let’s dig a bit deeper...

The effects of napping on cognitive performance have been vastly studied. Napping can restore alertness after a single night of sleep loss but not after two nights. Napping can also improve alertness and computer task performance in night-shift workers and healthcare workers. But there is a caveat. These studies also show that the outcomes of napping are influenced by the time of day and the duration of the nap and, especially, the stage of sleep people reach during their naps. Looking ahead, the science of napping needs to unravel somewhat. So perhaps, for now, just sleep on it.

Although cognition feeds into how your body can perform, measuring cognitive performance outcomes is very different from markers of physical performance. The findings just described should not automatically be extrapolated to your athletic prowess. What do we know about napping in athletes? Well, not much actually... In a cross-sectional comparison of non-athletes, sub-elite athletes, and international-level elite athletes, the elite athletes were simply better at taking naps on-demand than sub-elite and non-athletes; i.e. they had greater “sleepability”, and napping was associated with shorter sleep latency at night, i.e. a better ability to fall asleep once in bed. The comparison also found that napping was not related to nocturnal sleep disruption or daytime sleepiness. So, if elite athletes nap and they are awesome at their craft, should everyone be napping? Well, even though this was a robust study that used polysomnography, the gold standard tool for examining sleep duration and quality, correlation and causality are seldom aligned. Are elite athletes elite because they sleep, or do they sleep and/or nap more because they are engaged in the high training load of an elite athlete? Who is the chicken; who is the egg?

×

![]()

As an athlete, you may be getting insufficient sleep due to real-life constraints or because you are assigning a low priority to sleep relative to your other training modalities. Perhaps, before reading this, you were also uninformed about the powerful role of sleep in optimizing athletic performance (if that is true, please go back and digest my post on sleep, immediately). Yes, insufficient sleep impairs performance and sleep extension improves performance. Naturally, it is tempting to speculate that napping to increase your daily sleep time would be beneficial. But hold on to your sleepy horses. The effects of napping on cognitive performance are variable and dependent on many things. The direct effects of napping on physical performance are basically unknown. To my knowledge, one study has examined napping in runners and found that an afternoon nap did not affect time-to-exhaustion when running at 90% VO2max. Furthermore, cycling through multiple stages of sleep at night, from light to deep to REM and back again, is essential for being healthy. So, it would be most prudent to first invest your resources into optimising your nightly sleep before assuming that napping will supercharge your next race - napping should not replace prolonged sleep. That said, if early-morning starts are unavoidable and/or if night-time sleep interruption is common-place (hello newborn baby), correct sleep hygiene practices at night become imperative and embracing strategies for minimizing overall sleep loss, such as napping, may become a useful supplement.

×

![]()

Will your chronotype affect your recovery and performance?

Although our circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycle are genetically programmed to run on roughly a 24-hour cycle, each of us has a particular chronotype. Some people tend to stay up late and wake up late while others tend to go to bed early and wake up early. But, your actual chronotype can be determined using questionnaires to assess your preferred times for sleep, relaxation, and performance of mentally-demanding tasks. In very simple terms, your chronotype dictates that you are either a lark (early to bed, early to rise) or an owl (late to bed, late to rise), and there are extremes of both.Nearly 50% of the variability in being a lark or an owl is inherited in the genes gifted to you by your parents. Being male increases the probability that you are an owl while women are more likely to have a morning chronotype. Furthermore, the tendency to be an owl decreases with advancing age after adolescence. While your chronotype is influenced by genetics, sex, and age, it is very important to remember that the minimum recommended amount of sleep you need for maintaining optimal function stays the same: at least 7 to 9-hours a night, in adults (more in adolescents, children and new-borns).

There are a handful of people on Earth who truly only need small amounts of sleep each night. But, this is exceptionally rare. I have met many athletes who think they don’t need much sleep. But, is it a coincidence that such folks have, without exception, always appeared to be in need of more sleep? They are always tired, constantly injured, sometimes short-tempered, and never adapting and improving their performance as expected. If you are highly active, you probably need more sleep. I say probably because it is not completely known whether athletes need more sleep. But, in my recent post on sleep, I got under the covers with a bunch of sleep extension studies showing that athletes who sleep more, perform better. Win-win.

It is also not explicitly clear how athletes with different chronotypes are affected by different types of sleep patterns. Anecdotally, if my wife, an “owl”, attempts to get up early with her late chronotype, she stumbles around on the trails for a few hours like a zombie who has forgotten she likes to eat braaains. If she gets to bed late and lies in, she’s a hoot. I, on the other hand, am endowed with an early chronotype. Bed at ten, eyes open at six, ready to sing like a bird and start “larking” around in the mountains. If I go to bed late, I wake up feeling like I might well have sunk 9-bottles of imperial porter and rocked my socks off at Glastonbury before attempting some kind of session. While these are sentiments you may relate to, they are simply anecdotes. To understand how training adaptations and performance outcomes are regulated in people with different chronotypes and how different sleep patterns might interact with such outcomes, we must consider experimental evidence.

Chronotypes generally display peaks of several psychological and physiological variables at times corresponding to your owl-ness or lark-ness. Two key variables that have relevance to exercise performance and that also display a circadian rhythm in line with your specific sleep-wake cycle, are plasma cortisol levels and core body temperature. Cortisol tends to peak as you wake up while your body temperature typically peaks before you go to sleep. Since elevated cortisol or elevated body temperature can each cause premature fatigue and are associated with impaired exercise performance, it is tempting to speculate that chronotype may have relevance to training and athletic performance.

To address this speculation. A 2015 systematic review of 113 published articles concluded that technical skills in sports like badminton, tennis, and soccer, peak earlier in the day, typically in the afternoon; while muscle strength and anaerobic performance typically peak in the early evening. In general, the authors found that athletic performance was consistently better in the evening/afternoon than the morning, for all sports. However, this review did not specifically examine studies of athletes with different chronotypes. Fortunately, in 2017, Dr Jacopo Vitale published a systematic review in Sports Medicine examining just that. The review indicated that athletes with morning chronotypes (larks) were found to feel less fatigue, have a lower RPE, and have the fastest race times in the morning for half- and full-marathons, as well as 2000-metre rowing time trials, and 200-metre swimming time-trials, when compared to athletes with other chronotypes. Furthermore, evening-chronotype athletes (owls) needed more time to be “ready to go” after waking up than morning-chronotypes. This transition time between sleep and wakefulness is known as “sleep inertia”, which presents itself through the medium of disorientation and motor coordination. Upon waking, sleep inertia is more extreme in owls than it is in morning-chronotype larks.

Another aspect to consider is how your sleep hygiene may be affected by a late-evening workout. A recent experimental study from Dr Vitale found that sleep quality, after an evening session of S.H.I.T. (short high-intensity interval training), was poorer in morning-chronotype soccer players when compared to evening-chronotype players. Furthermore, there were no differences in sleep quality between the two chronotypes when the S.H.I.T. was taken in the morning.

To summarise, the research to date indicates that larks have a performance advantage over owls. Since the vast majority of races occur in the morning, this may favour early chronotype athletes. However, owls’ sleep may be less affected following an intense workout than larks, offering late chronotypes more time-flexibility in their training with respect to sleep quality. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the current studies are few and far between and there is considerable inter-individual variability in performance outcomes between subjects. Also, importantly, it remains to be examined whether chronotype can be “trained” and, therefore, changed to help one adjust to racing at times of the day when you’d rather be singing like a lark or hooting like an owl. Watch this space, as I am sure scientists will go down that path very soon...

×

![]()

What can you add to your training toolbox?

Given the observations that there are particular times of day when we are, on average, most “ready to go again”, adjusting training time based on an athlete’s chronotype might one day be prudent, particularly given the rapidly growing interest in the chronobiology of exercise and nutrition. But, the current evidence does not allow practitioners to speculate on the optimal time to train based on chronotype and, as you are no doubt blissfully aware, many other key aspects of your exercise-recovery cycle, like training load, nutrition, and rest, also play a massive role in governing your adaptations and eventual performance outcomes.The recommendation is to sleep a minimum of 7 to 9 hours a night. As an athlete, you may need more and the evidence certainly suggests that sleeping more will increase your physical performance. As I frequently remind people, you are the only you. Learn to understand your natural sleep habits. Assess your own individual need for sleep and compare your mood, vigour, and performance after periods of poor versus great sleep. If you need to nap, nap, but prioritise identifying the areas where you could improve your sleep hygiene to maximise the quantity and quality of your nightly zzz’s. For now, don’t waste valuable energy stressing over or trying to toy with your chronobiology because not enough is known about how to optimise your training based on your chronotype.

Thanks for joining me for another “session”. Bye for now and, whether you like to sing like a lark or hoot like an owl, get your sleep hygiene in order to keep your engine roaring like a lion.

Disclaimer: I occasionally mention brands and products but it is important to know that I am not affiliated with, sponsored by, an ambassador for, or receiving advertisement royalties from any brands. I have conducted biomedical research for which I have received research money from publicly-funded national research councils and medical charities, and also from private companies, including Novo Nordisk Foundation, AstraZeneca, Amylin, A.P. Møller Foundation, and Augustinus Foundation. I’ve also consulted for Boost Treadmills and Gu Energy on their research and innovation grant applications and I’ve provided research and science writing services for Examine — some of my articles contain links to information provided by Examine but I do not receive any royalties or bonuses from those links. These companies had no control over the research design, data analysis, or publication outcomes of my work. Any recommendations I make are, and always will be, based on my own views and opinions shaped by the evidence available. My recommendations have never and will never be influenced by affiliations, sponsorships, advertisement royalties, etc. The information I provide is not medical advice. Before making any changes to your habits of daily living based on any information I provide, always ensure it is safe for you to do so and consult your doctor if you are unsure.

If you find value in this free content, please help keep it alive and buy me a beer:

Buy me a beer.

Buy me a beer.

Share this post on your social media:

Want free exercise science education delivered to your inbox? Join the 100s of other athletes, coaches, students, scientists, & clinicians and sign up here:

About the author:

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.

I am Thomas Solomon and I'm passionate about relaying accurate and clear scientific information to the masses to help folks meet their fitness and performance goals. I hold a BSc in Biochemistry and a PhD in Exercise Science and am an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist and Personal Trainer, a VDOT-certified Distance running coach, and a Registered Nutritionist. Since 2002, I have conducted biomedical research in exercise and nutrition and have taught and led university courses in exercise physiology, nutrition, biochemistry, and molecular medicine. My work is published in over 80 peer-reviewed medical journal publications and I have delivered more than 50 conference presentations & invited talks at universities and medical societies. I have coached and provided training plans for truck-loads of athletes, have competed at a high level in running, cycling, and obstacle course racing, and continue to run, ride, ski, hike, lift, and climb as much as my ageing body will allow. To stay on top of scientific developments, I consult for scientists, participate in journal clubs, peer-review papers for medical journals, and I invest every Friday in reading what new delights have spawned onto PubMed. In my spare time, I hunt for phenomenal mountain views to capture through the lens, boulder problems to solve, and for new craft beers to drink with the goal of sending my gustatory system into a hullabaloo.

Copyright © Thomas Solomon. All rights reserved.